Report

advertisement

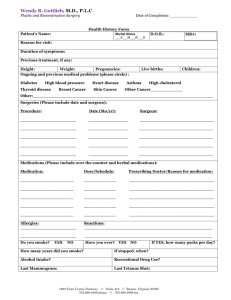

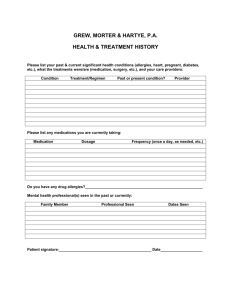

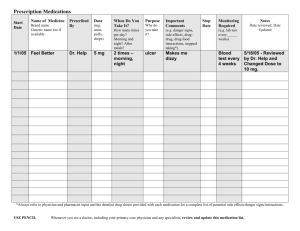

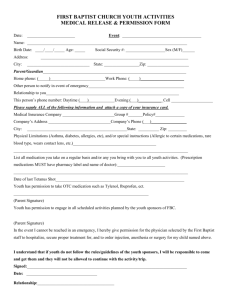

Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 1 MyMedMinder: Personal Health Records To Maintain Medication Lists Patti Abbott pabbott2@son.jhmi.edu Chris Bassler cbassler@wam.umd.edu Okpetoritse Pessu opessu@gmail.com Project Website: http://129.2.168.8/medminder/ 2 December 2006 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 2 Abstract MyMedMinder is a web based service designed to assist users in organizing and keeping a history their medications. It is known from the literature that patients are challenged to keep an accurate record of their medications, which can result in error. This service will be beneficial in that it allows users to organize their medication history automatically and store it digitally. Implementing MyMedMinder as a website allows for instant access of these records from any location with an internet connection. For those who feel more confident in possessing a hard copy of their medication record, the option to print to paper is available. The system allows patients, via a password, to review and update their medication histories as needed. We hope that this service will help to reduce confusion among patients, assist doctors in treatment and help prevent deadly mistake resulting from known drug interactions. Credits This project was the result of a team effort. Pat Kessler assisted with the development of the mockup/prototype as did other members of the team. Okpe completed the initial database development. Patti and Chris produced the written reports and worked intensely on the development and refinement of the prototypes. Final usability testing and analysis was completed by Patti, Okpe, and Chris. The final report write-up was completed by the combined effort of Okpe, Chris and Patti. Introduction Polypharmacy is a common problem in older adults, and is defined as the concurrent use of several medications at the same time. While the use of several drugs at the same time is not necessarily a bad thing, it is a difficult task for the average older adult to manage. Polypharmacy often results in missed medications, confusion, and error. The causes of polypharmacy are multidimensional. Most patients see more than one provider, referral to specialists is common, and a “provider” is often times not a physician. Therefore, it is common for patients to be treated by a myriad of providers, each prescribing medications for different symptoms. From a providers perspective, the complexity of trying to prescribe medications for health conditions without an accurate understanding of the current medication regimen results in an increased chance for adverse reactions, drug interactions, and medication errors. From the patient’s perspective, barriers to compliance with treatment arise. Patients are confused about which drugs to take when, and why they are taking the medications in the first place. It is known from the literature that patients who participate in their care to a greater degree have better healthcare outcomes. Being knowledgeable about what they are taking, why they are taking it, and the most effective ways to take medication results in patients who are better able to help manage their own disease. The challenge here is twofold. First, how can we encourage patients to play a more active role in maintenance of their own health conditions and second, how can we assist patients in organizing their medications to reduce confusion and the chance for error so that they can play that more active role? There are many methods by which the first question is attempting to be answered. For the purposes of this proposal, we will focus on the use of an “Electronic Personal Health Record” or e-PHR for patient use. The e-PHR movement is gaining in Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 3 popularity in the US, and there is a need to use user-centered design to build the e-PHR. Since the e-PHR is designed for primary use by the patient, the user group therefore is the patient, not the medical establishment. Our goal will be to design our prototype based on the needs of the patient as the primary user. Discussion of Previous Work/Studies with References Barnsteiner, Jane H. (2005). Medication Reconciliation. AJN. http://www.nursingcenter.com This article discusses the errors of health records as they are currently implemented, and also looks at solutions and their pros and cons. The amount of errors involved with medical records is huge, according to the article. A number of paper solutions and EMR (electronic medical record) are discussed. The main problem of EMR, which our PHR will have to deal with, is user omissions. Apparently, both patients and clinicians have a fair number of them. Endsley, S., C. Kibbe, D., Linares, A., Colorafi, K. (2006). An Introduction to Personal Health Records. Family Practice Management. www.aafp.org/fpm, 57-62 The article describes how the use of electronic PHR help patients on their medicine usage and also doctors so they don’t prescribe medicine that may be in conflict with a patient’s current medications or that the patient may be allergic to. The article emphasizes that the PHR should be stored electronically. This is because the aftereffects of Katrina when a lot of patient’s records were lost and patients seeking healthcare had no records which made it difficult for doctors to prescribe medications. This article relates to our project in the sense that patients prescription usage is recorded in our “MyMedMinder” implementation of the PHR. This supports the goal of our project. It will also assist doctors in prescribing appropriate medications. Gleason, Kristine M., Groszek, Jennifer M., Sullivan, Carol, Rooney, Denise, Barnard Cynthia, and Noskin, Gary A.(2004). Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004; 61:1689-95 The article talks about how having different medical records for each patient could be harmful. The study in the article focused on patients providing their medical history to doctors and then matching the information they give with records on file. The results were that there were discrepancies with the information given by patients and that recorded on file. The article proposes a universal medication form to encourage patients to keep track of their medication and allergy information. This relates to our project because we are trying to create an interface that encourages patients to keep records of their medicine usage and making the process of storing their medication histories easier. Kim, Matthew I., Johnson, Kevin B. (2002). Personal Health Records: Evalutation of Functionality and Utiliy. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Assocation. Volume 9, Number 2, 171-180 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 4 The article evaluated the usefulness of 11 web-based PHRs. Some of the information is relevant to our project, but some of it is not. The major problem with almost all of the web-based PHRs, according to the article, is data entry and validation. There was no functionality with the purpose of making data entry easy for the user. This seems like a major issue we will need to deal with, because the user must take an active interest in keeping the record up to date, if it is difficult to update, then the user will be discouraged. Porter, S., Kohane, Z., & Goldman, D. (2005). Parents as Partners in Obtaining the Medication History. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 12(3), 299-305. This article described the development and use of a touch-screen kiosk in an Emergency Room for use by parents in recording their child’s medication history. The goal of the study was to examine the accuracy of medication history entered by laypersons. The results of the study showed that the parents’ reports of the child’s medication history were more accurate than the nursing documentation of the same. Parents had most errors on the medication name aspect of the recording process. This article informs our project by emphasizing that a laypersons recall of a complex drug name may be better with some sort of computer aided support (like a list of medications that the layperson can pick from). It also shows us that the accuracy rate of layperson entry of medications can exceed that of a provider. Santell, John P., (2004) Reconciliation Failures Lead to Medication Errors. Joint Comission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 32(4), 225-229. This article discusses the implication of poor communication of medical information at transition points of care and the known medical errors it has caused. It discusses the need to incorporate a set of protocols and processes at each intersection of a patients care. Common types of error and their typical frequency and severity are reviewed in this article. A suggested list of improvements is included. This article shows us where common errors in relaying information occurs, and there are some errors noted that we will need to be aware of. Saufl, Nancy M. (2006). Reconciliation of Medications. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 21(2), 126-127. This article discusses reconciling medication during a patient’s transition of care. The specific types of information that need to be reconciled is covered, as well as specific steps that should be taken at different points in a patients care. The need for standardization, at least at the level of specific organizations, is discussed. This relates to our project by pointing out common errors in the transcription of medication histories. Tang, Paul C. & Lansky, David (2005). The Missing Link: Bridging the Patient– Provider Health Information Gap. Health Affairs. Volume 24, 1290-1295 The article described the how the use of PHR could help patients play active role in their healthcare by entering information about symptoms, medicine taken, personal exercise program, and other information regarding their health. The article also talks about how the PHR should be “lifelong and comprehensive” and also to be accessible for any place at anytime and most important of all, be secure. This article relates to our Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 5 project because it emphasizes the fact that if patients record their medicine usage in a system, it helps them play active role in their health care because they are able to present it to their doctors so the doctor knows what kinds of medicine they are taking so as not to prescribe conflicting medications for the patient. Tobacman, J., Kissinger, P., Wells, M., Prokuski, J. Hoyer, M., McPherson, P., Wheeler, J., Kron-Chalupa, J., Parsons, C., Weller, P., & Zimmerman, B. (2004). Implementation of personal health records by case managers in a VAMC general medicine clinic. Patient Education and Counseling . 54 (1), 27-33. This study was done at a VAMC (Veterans Affairs Medical Center) in an outpatient clinic. Although they did not use a computer approach to the PHR (they used a checkbook sized series of cards), the study illustrated several things which may impact out project. What the study did show was that approximately 50% of the study participants had no record or personal health data at all prior to the study (such as doctors, test results, medications, etc.). After the study, 60% of the patients who participated had continued to enter data, make changes, and it stimulated better dialog between the patient and their providers. Other implications for our project are that “build it and they will come” does not hold true for all. Forty percent of the study group was not interested and did not participate in their PHR. The investigators were not sure why, but it only adds to the need to make the interface very easy and appealing in order to influence use, which is something that will influence our project. Tran DT, Zhang X, Stolyar A, Lober WB. (2005) Patient-centered Design for a Personal Health Record System. AMIA 2005 Symposium Proceeding. 1140. This project focused on designed a user interface for a personal health record system that would model how patients view their health information. User needs were assessed to created two different user interfaces for the Patient-Centered Health Record System. Their design focus was on discovering useful content to include and ensuring that the user interface was helpful, intuitive and easy to use. Wang, M., Lau, C., Matsen, F., & Kim, Y. (2004). Personal health information management system and its application in referral management. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 8(3), 287-97. This study created a web-based PHR for patients in a surgical clinic to ease the referral process of having to gather all the information at the time of visit from the patient either verbally or by a written medical history form. The results showed that patients were willing to learn to use the PHR if they perceived security and benefit (like better care) and were willing to fill out detailed forms as well over the web. Providers (those getting the referral) liked the system; they were appreciative of not having to illicit the information verbally from the patient and then write it all down. This relates to our project by showing that patients and providers may be willing to use a web-based PHR platform if their security can be guaranteed and if they find benefit to the work. Wuerdeman, Lisa, Volk, Lynn, Pizziferri, Lisa, Tsurikova, Ruslana, Harris, Cathyann, Feygin, Raisa, epstein, Marianna, Meyers, Kimberly, Wald, Jonathan S, Lansky, David, and Bates, David W. (2006). How Accurate is Information that Patients Contribute to their Electronic Health Record? AMIA 2005 Symposium Proceedings. 834-848 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 6 The article compares the results of an EHR (Electronic Health Record) with patient's responses about health records. Basically, patients have good knowledge of their basic health record, but are more likely to know the answers to “yes or no” questions as opposed to specific test results (for example, exact percentages). The article states that the rise of PHRs could give patients the power to contribute to their health record much more easily, relating to our project. Most importantly, the article shows that patients have a reasonable knowledge of their own record, which a PHR would enable them to keep precise track of. Relevant Websites http://www.ihealthrecord.org/ This is a “free” website that offers a free location to store personal health data. The site makes a good case for why the idea is a good one. The interface (limited access unless you sign up) seems to be relatively easy to use. The medication aspect is inaccessible, therefore could not really be judged. The difference between this and our project is that our goal is to put the data in the hand of the patient rather than having it stored on a third party server. This could cause suspicion and fear of privacy or security loss, and aspect that our project would not have to deal with. http://www.ahrq.gov/ppip/50plus/ This is a government sponsored website called Putting Prevention Into Practice (PPIP). This is an online resource – but it is designed to be printed out by the patient. There is a tool on here called “Medication Minder” which is designed to allow patients to record their medications. It is very flat, and the process of using paper does not meet the needs of a flexible and transportable medication record. Our project can benefit from the PPIP page by using the structure that has already been validated by funded federal studies. We can improve on it by taking it from paper fro a file structure. http://www.medicalert.org/E-Health/ The Medic Alert Corporation is trustworthy and offers a thumb drive storage device for the patient. The data is also stored on the MedicAlert database. We are unable to view the interface as this is not a free service. There is a demo, but the view is limited. This relates to our project in that the use of the thumb drive puts the data in the hand of the patient, which is one of our goals. It was unfortunate that we were unable to view the interface or input mechanism. We believe that the use of the MedicAlert database and a fee for use is a negative. The reputation of the company is a positive. Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 7 Design The MyMedMinder website was designed to attempt to provide the most possible features while maintaining an easy to navigate design. The transition diagram and screenshots below will depict our final prototype and the paths users can take while using this application. See Diagram 1. Begin Here Home About New Users Login Create Acct. ***Can be reached by all screens Help Logout View Print Add Welcome Prep. Info Enter Form Opens new window By Name By Reason By Name By Reason By Doctor By Doctor By Date By Date Legend: The use must be logged in to access these pages The user does not have to be logged in to access these pages General Information Diagram 1 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Screen Shots The final version of the site is represented in the following figures (examples) including the HELP screens. The live version can be viewed at: http://129.2.168.8/medminder Prototypes follow these screen shots. Fig 0.0: The opening screen when accessing MyMedMinder Fig 0.01: Example of the HELP file (consistent across all screens) 8 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 0.1: Available to non-members, this screen gives an overview of MyMedMinder. Fig 0.2: The New Users Page. Users access this and are able to perform two functions, either “Learn More About MyMedMinder” or go directly into “Create a New Account”. 9 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 0.3: Create Account Page with information about creating a new account. Fig 0.4: Login Page. If people accidentally end up here without a password, they can click to register. 10 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 11 Fig 0.5: The welcome screen that a member will see after a successful login. The system verifies their name to be sure they are logged in properly and it also relays the number of medication the user currently has stored in the database. Users are able to review, add or print medications from this screen. Fig 0.6: The options for viewing medications that have already been entered. Users are allowed to review by date, in alphabetical order, by prescriber or by reason for taking. Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 0.7 Medication view which has been chosen to be viewed by name of drug. Fig 0.08: Medication View Sorted By Name of Prescriber 12 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 0.09: Medication View Sorted By Reason for the Medication Fig 0.10: Add screen with instructions. 13 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 14 Fig 0.11: The standard form for entering medication into the database. An image to help with terminology is included for user reference. Development process The development process for the MyMedMinder site consisted of two main steps. First we met as a group for brainstorming sessions where we discussed our own beliefs of what we believed the system functionality should include. The brainstorming sessions began as meetings after class periods. The group members spent this time to familiarize ourselves with the project and its requirements. Each member of our group decided to prepare a conceptual design of the system which would then be brought back to the next meeting and compared. Our final design was they derived from the combination from all the prototypes. Each had strengths and weaknesses, and we believed that the diversity of thought strengthened the design. The decision to create a web based application for this project was unanimous because it would increase accessibility and also had the greatest chance of being familiar to users. We knew from looking at and discussing the Pew Report on public use of the internet that the number one reason that Americans (in general) use the internet is for medical information. Therefore, although we understand that not everyone has access to the Internet, that is is becoming more common and acceptable for the general public. We also know that people who do not own their own computer are increasingly using internet cafes and public libraries as areas to gain access to the internet. We consulted friends, family, and clinicians to create a better idea of functionality. After working within our group, we compiled a prioritized list of features that we wanted to implement.. In developing the prototype conceptual designs, we believe that allowing each member to be creative resulted in several benefits. It allowed us to better understand the Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 15 nuances of the interface, it made us think deeper into the branching logic, and helped us to piece together newly gained information about usability and interface design principles. Team members chose a variety of formats to use for the draft including Microsoft Word and Powerpoint as well as HTML developed in Adobe Dreamweaver. In the discussions that ensued as we compared each design, we debated the pros and cons of each design and gradually merged all of the concepts into one final prototype that was constructed in one of the team members FTP site. This enabled us to work on the prototype together, regardless of geographic location or time of day. We tweaked the prototype until we believed that it resembled most closely our conceptual design. The screen shots ahead depict some of the features we chose to keep as well as some of the design differences in similar situations. Low fidelity prototype examples follow: Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 1.1: A welcome screen designed in MS Word 16 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 1.2: A login screen that doubles as the welcome screen in HTML. 17 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 1.3: Menu prototype for user navigation 18 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 1.4: Suggestion to put form in a table 19 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Fig 1.6: Suggested design for viewing and adding medication information 20 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 21 Fig 1.8: A Completion View highlighting the idea of a standard tool bar across the bottom. Prototype Testing Our team handed in the prototypes represented above and received critiques from the instructor. We modified the prototype based on that critique. The consolidated conceptual design that we began to model our physical prototype upon is represented in the screen shots below. We did discover during the actual building of the prototype that we were unable to exactly replicate several of the features in exactly the way that we had envisioned on paper. The core functionality was modeled successfully in our initial prototype however. The prototype testing process will be described after the presentation of the revised screens (below): Revised Prototype (Figures 1.9) Figures 1.9 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Figures 1.9 22 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Figures 1.9 23 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Figures 1.9 24 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Figures 1.9 25 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Figures 1.9 26 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 27 Figures 1.9 Prototype Testing We conducted small scale prototype testing using several people representative of the final end user group (primarily parents and older relatives). Each person was asked to sit down at the interface represented above (we used the ftp site prototype) and use the Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 28 system to record several of their own medications. We chose older relatives based on knowledge that they were taking medications, we were able to readily access them, and the team members were with the relative as they worked through the system. This enabled us to directly observe problems that the users had with the interface. During the observation period, we asked the family members to verbalize what they thought they were supposed to do as they were walking through the process. If something confused them, we asked them to tell us about it. We did not instantly help them solve a problem or a question in the process. Instead we let them try to figure it out on their own. If they were really hung, we gave them advice and took note of the struggle areas, and why the user had difficulty. The next step of the process was to compare notes across the team to see if common areas of user issues arose – which they did. There were several fields that the wording was confusing and several spots where the users were not sure how to progress or what the next step was. For example, we noted that at the completion of the data entry process, there was no function visible for the user to say “finish and save”. The common toolbar across the bottom was ambiguous for that particular function. We also noted that the wording of the question requesting the user to enter the medication concentration caused real confusion in the user. There were several other small issues that required us to clarify. We did note that while there were several areas that people had difficulty across the board, some of the struggle spots were unique to a particular user/subject. Because we only tested 3 users in the prototype stage, we decided that we should address each concern, even if only one person had an issue with it. One area of real concern was the difficulty in entering the medications into the form fillin. We believe this was due to the terminology – even the development team struggled. The result was a change in several aspects of the interface for our first revision. While not perfect, we believed that a reasonable way to graphically represent the concepts from a label was to include a graphic that the users could reference if confused. It seems to have helped considerably, but it is still a difficult aspect that could use more work. Review of the group in the first revision discovered more issues, so a second revision was undertaken before we ended up with our final version. The final version that was used for usability testing can be found earlier in this report – on pages 8-13. There were some areas that, had we had more time and more expertise, we would have liked to alter for the final. We have represented these aspects in our conclusion section as areas where more work is needed. Usability Testing SCENARIO – We conducted our usability study with 6 users to evaluate our final version of the interface to MyMedMinder. The users were purposively selected from a candidate group of users similar to those who may use MyMedMinder. While we planned to focus on older adults, ages 65 and up, the group believed that younger people might also find value in MyMedMinder, particularly since some may be caring for aging parents. Subject had to be able to read and speak English, and be without significant mental or physical handicaps. Familiarity with a computer was a pre-requisite for the evaluation of MyMedMinder. Subjects will be invited to participate by members of the project team, and included parents, grandparents, colleagues, neighbors and friends. Subjects were instructed on the purpose of the study, any risks involved, guaranteed anonymity via the use of a coded id number (not a personal name). As Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 29 planned, they were instructed that the focus of the study is on the interface and not themselves or their performance. They were instructed to enter their medications into a web-based interface so that we may study their actions and gain their feedback on the process and the system interface. TASKS – Users were tested at a standard PC in a quiet location. We decided to provide 3 of the same medications to each subject, using a printed (simulated) pill bottle label. They were asked to use the system to enter those medications. The subjects were encouraged to work with the interface themselves without any involvement of the researchers – unless the subject got to a point of being totally hung. At only one time with one subject did this occur. The researchers took note of issues that arise with the user – such as areas where they struggled, areas that they made errors or expressed confusion, and any missteps that occured. Steps: 1. Click into MyMedMinder 2. Browse, learn about system, then make a selection for “new user” 3. Login 4. Review information screen/choices and explore as desired 5. Enter medication data as requested 6. Review entry 7. Revise entry if necessary 8. Save entry 9. Repeat if necessary for additional meds or if editing necessary 10. Review final entry 11. Save session and/or print record. 12. Logout PRE-TEST – Prior to participating, the users were given a short pencil and paper demographic questionnaire. No names or identifying information were used. The subjects were given a code number which was used on all testing (computerized and paper notes) to protect identity. Data that was collected included: Age, gender, years of computer experience Number of medications taken Experience with Internet (range from novice to expert) REVISED POST-TEST FOR EVAULATION OF PROTOTYPE/USABILITY (Actual evaluation handed out to subjects) POST-TEST – Evaluation Testing for MyMedMinder We sincerely appreciate the time you have taken to participate in this study. All data will be anonymous, and we will not make any effort to match these surveys to participants. The focus of this study is not on how YOU perform – instead the focus is on the interface and how we can improve it to make the use of MyMedMinder easier and more user friendly. Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 30 After completing the exercise of entering data into the system, we would like for you to share your opinion with us. We would appreciate it if you would complete this very short survey. Simply read each question and put a mark in the box that best corresponds to your feeling or opinion about your experience with MyMedMinder. Please only mark one box per question. If you change you mind, make sure to make your correct answer obvious to us by marking it clearly. The test is structured on a scale. For instance, in question one, if you thought the system was wonderful, you would make a mark in the box below the text of “wonderful”. If you thought the system was “terrible”, you would put your mark in box number 1, right below the word “terrible”. Boxes 2, 3, or 4 allow you to pick somewhere in between. What is your overall reaction to this system? (please answer all 5) Terrible ………….………………………….Wonderful 1 2 3 4 5 Frustrating …………………..........................Satisfying 1 2 3 4 5 Dull …………………………………………Stimulating 1 2 3 4 5 Difficult ………………………………………..Easy 1 2 3 4 5 Rigid …………………………………………...Flexible 1 2 3 4 5 1. What do you think about the appearance of material on the screen?(please answer all 3) Too much on one screen …………………………………Too little on screen 1 2 3 4 5 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 31 Items arranged logically…………………………………Items arranged illogically 1 2 3 4 5 Screen sequence clear……………………………………Screen sequence confusing 1 2 3 4 5 2. What do you think about the saving and editing process? (please answer all 3) Easy to correct mistakes…………………………………Difficult to correct mistakes 1 2 3 4 5 Saving data was easy…………………………………….Saving data was difficult 1 2 3 4 5 System was too slow…………………………………….System was too fast 1 2 3 4 5 3. How easy was the system to learn to use? (please answer 1) System was easy to learn………………………………..System was hard to learn 1 2 3 4 5 4. Do you have any comments that would help us to improve the system in any way? Thank you very much for your participation! Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 32 Results Narrative Reports By Subject Subject 1: Subject 1 was a 58 year old male who had 8 years of computer experience. This subject takes an average of 2 prescription medications daily. By self assessment, this subject considers himself an expert with the Internet. Subject 1 has a great deal of medical experience. This subject was readily able to gain entry into the website for MyMedMinder. Subject 1 remarked that he liked the colors and the layout of the opening screen and specifically asked about the graphic/picture and said he found it “appealing”. He was curious about why we found it necessary to include the statement about “best viewed with IE 6.0 or higher”, but we attribute this to the experience level with the web. The subject also expressed that he wished he did not have to scroll to read the whole first page. Similarly, he commented about the icons being located out of site at the bottom of the active page – although he managed well and relied heavily on the toolbar icons. Issues that were managed probably due to the experience level of this subject included the data entry function and the help function. In regards to the help function, the user expressed that he wished that there was item specific help. While he appreciated the general help and found it useful and reasonably well done, there were issues that he needed help with that there was no help information for; in example, how to “edit” and existing record. This actually pointed to his bigger concern about the inability to remove, totally, records in the system. For example, if a medication is given and stopped due to a reaction or something, there was no way to note that or remove the medication. If we put this in context of a patient-centered effort, they must have the ability to do this. The next big issue was in the medication entry process. It is inherently complex, and it took awhile for subject 1 to figure you it and perform the tasks successfully. He pointed out that the image was too small and that it might be helpful to somehow relate each fillin with the area on the graphic example where users could refer their attention. Subject 1 suggested that the display of medications (for review or printing) could use some formatting work as it was not pleasing to the eye and was a little confusing at first to interpret. Finally, he was also quite concerned about the inability to remove records from the database. Subject 2: Subject 2 was a 27 year old male with 7 years of computing experience. He rates himself as an expert on the Internet. Subject 2 takes no medications, but is a parent and has a child who receives allergy medicines twice a day. Subject 2 expressed an interest in using such an application if the need arises. This subject has no medical experience. Subject 2 had no expressed issues whatsoever in navigating through the system, however, there was an observed change in the concentration level at the area of entering the medications. The subject was observed to spend several minutes reading and rereading the questions and studying the graphic intently. Several slips were observed, but were corrected before saving the entry. This subject did mention that it might be good to have better and more specific help functions for this process. Also this subject suggested that we use better error prevention techniques – for instance he noted that he could enter text into the date field. Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 33 Subject 2 did also asked why we are requesting certain information in the “create new account” section since it did not seem to be used for anything and that it might make some people hesitant to participate. While subject 2 did not have any major issues, the rating on the evaluation tool was tepid. Subject 3: Subject three was a 25 year old female with 4 years of computing experience and a moderate level of expertise on the internet. She takes no meds, but also is asked by her grandfather routinely for help in refilling prescriptions and helping with his medications. She expressed verbally that this might be of a help to her for helping with her grandfathers medications more so than her own. Subject 3 expressed a like of the opening screen. She liked the light blue and the picture. She said she found it “soothing” and interesting all at the same time. Subject 3 had no difficulty navigating through the first few screens. This subject choose to just click around, exploring the site before getting down to work. This actually resulted in a little bit of confusion – for example, she clicked on “Returning Users” first and what was in there did not make sense to her. She stated that “this is what I get for poking around and not going at this in a structured way.” Subject 3 was allowed to continue exploring, then settled into the task at hand. Subject 3 noted that she wished she did not have to scroll through a page to read it all and also commented that finding the maneuver icons at the bottom seemed to be odd. She suggested that we move them to the top bar so that all maneuvering possibilities would be viewable from any screen. She, like everyone else, had to take some time to figure out the data entry screen – and was frustrated when she accidentally hit “clear form” by accident and found that there was no easy way to reverse that action. She also asked “how do I remove my data from this system?”, which highlighted the same issue brought up by others. This subject was pleased with the application and encouraged us to continue working on it because she viewed it as “important”. Her primary struggle point was in the “Add a Medication” process, but stated that she found the graphic of the pill bottle helpful in interpreting what data was required. Subject 4: Subject 4 was a 46 year old female with 3 years computer experience. She considers herself as a moderate in regard to internet expertise. Subject 4 takes 2 meds a day, but mentioned that she has 2 children who have severe allergies and she does them twice a day and elderly parents – all of whom take medications and this subject feels as though she has some responsibility for all of them. She represented that she “takes” 4 meds a day. Subject 4 seemed to be distracted and just kept asking “what do I do next?” instead of concentrating on the tasks at hand or trying to figure it out on her own. Subject 4 was asked to continue to try and work with the system – although hints were given by the observer/researcher. The impression was that this person just wanted to “get it over with” instead of doing a thoughtful testing. She moved quickly through the procedure, entering all three meds without major incident, however. It was noted that once she got the hang of medication entry on drug number 1 that the next two went in easily. She did comment that some of the terms were Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 34 confusing, specifically that the word “concentration” is used twice in the form fillin to represent two different data elements. Subject 4 also commented that the help screens were not specific enough to offer some of the granular help that she needed. She did like the pill bottle graphic, saying that it helped her figure out what was needed. Subject 5: Subject 5 was a male who was 22 years old. He had 6 years of computer experience and considered himself and expert on the Internet. He does not take any prescription meds, but he does use OTC on occasion (such as Tylenol for headaches) therefore he chose 1 as the number of meds that he took. Subject 5 did not seem to have any difficult with the application. He liked the concept and expressed that “it was about time” that someone put this in an automated format since he had been reading about medication error in the press and thinks “something must be done”. This subject also mentioned that he thought the medication entry screen could be improved, but did not offer specific comments in that regard. He did mention that there needed to be a way to remove records. Subject 6 did not have any difficulty printing or saving and thought that the help file was sufficient. Subject 6: Subject 6 was a male who was 79 years old. He takes 12 medications a day – a combination of prescription and OTC (although primarily prescriptions). He has 4 months of computer experience and considers himself a novice on the internet. Subject 6 was our most challenged subject – yet he represented a prime user group for an application of this type. He needed more support than the other subjects however, the observer only had to actually intervene once. While the subject did not verbalize this, we noticed that he seemed to be squinting and tipping his head back and forth to use his bifocals. It was more difficult for him to scroll because of vision and hand coordination issues. For example, it would take him a period of time to find the text, then he would have to look for the mouse – which made him lose his place in the text. It seemed to indicate that we should try to get as much as possible on one screen so that users do not have to scroll. The tradeoff is that the text has to be large enough for those with elderly eyes to see. Related, we noticed that it was more difficult for this elderly person to click on the top toolbar as well. He really had to “aim” and it was hard for him to hit the target. Also, he mentioned that the font was a little small and hard to see. Subject 6 struggled in the add medication process. This is where the observer had to intervene to assist. The user commented that it was hard to understand, and asked why certain text was “red”. He said that it would be helpful if the data entry “slot” could automatically point to the example label. He also said that the graphic was too small. Subject 6 was somewhat confused with the options to display, but with a little practice he figured it out and ended up liking it. He said that it helped him to organize his meds based on what his goal was, for example, if thought that if he wanted to look up his medicines that he had taken for pain.. The display however was a point of his criticism – he wanted to know why the columns did not line up. Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 35 Subject 6 also had some issues with the help button – especially since one option took him to “About MyMedMinder” and he did not know how to get back to where he started. He wanted to know where he was in the process – and he may have benefited from a “progress” screen similar to what appears on an airline ticketing site. Subject 6 also had difficulty with the print and save function, most likely related to a lack of expertise in working with printing and saving dialog boxes. He ended up abandoning the effort to save, but mastered the printing function. There was some confusion expressed by Subject 6 understanding conceptually the difference between returning home from within the secure area and returning home from the public area as well. He asked “why when I hit the home button I get two different views? Why does that happen?” Finally, subject 6 did find value in the site and verbalized that he thought it was worth the effort to put his medicines in because he has so much trouble keeping it straight. Key Questionnaire Results in Graphs There were a total of 5 questions on the evaluation. The first four questions were based on the QUIS and were based on a Likert Scale with 5 data points. The fifth question was free text. Questions 1-4 are represented in chart 4 below, but are plotted only on the basis of summary scores. Summary scores are derived by adding up the totals from each sub scale contained within a single question. For example, question 1 actually has 5 sub-questions contained within it, therefore for question 1 all raw data was averaged across all subjects and reported as an average for the overall question. The actual survey is included earlier in this report as is the raw data (nonsummarized).Summary statistic regarding demographic data are graphically reported below. All raw data is also provided in Appendix 1. 90 9 80 8 70 7 60 6 50 5 40 4 30 3 20 2 10 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 Subject # 5 6 Number Years Computer Exp. Age in Years Age By Experience Age in Years Experience Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 36 Chart 1: This chart represents the age relationship to experience, with experience being represented with the line and the legend on the right. The oldest subject has the least experience. N=6 Gender 4.5 4 3.5 Frequency 3 2.5 Series1 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 1 2 Male = 1; Female = 2 Chart 2: Gender Distribution; N=6 Number of Medications 14 # of Medications/Day 12 10 8 Series1 6 4 2 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Subject # Chart 3: Number of medications per subject – demonstrating skewing potential of subject 6 Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 37 Summary Scores/QUIS 3.6 Average/Summary Score 3.5 3.4 3.3 3.2 Series1 3.1 3.0 2.9 2.8 2.7 1 2 3 4 Question # Chart 4: Summary Scores (Averages) for Question 1-4 Question #1 is “What is your overall reaction to this system?” Question #2 is “What do you think about the appearance of material on the screen?” Question #3 is “What do you think about the saving and editing process?” Question #4 is “How easy was the system to learn to use?” Question #5 is free text/comment area and that will be reported separately (as part of “key comments” at the end of the results section. Analysis of Usability Test Results Six subjects participated in the usability test of the final version of MyMedMinder. They subjects ranged in age from 24 years old to 79 years old. Four were males and 2 were females. The average number of daily medications taken was three, with a wide range/skew (0-12). The range of computer experience was wide, from 4 months to 8 years, with the older subject having the least number of years of experience. After consenting and completing the pre-study demographic questionnaire, subjects were given the identical three prescriptions (on a simulated paper label like one would find on a pill bottle) and asked to record the medications in the system while we observed. Observers took notice of where users struggled and took notes. In only one instance did we have to step in and help, and that was with an older gentleman who did not have much computer experience and was growing frustrated. Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 38 We used a modified version of the QUIS that was revamped after the instructor critique in early October. Unfortunately, our evaluation results came out rather nondescript. Most everything ranked in the middle (averages reported): • • • • • Overall Reaction (scale of 1-5) Appearance of Material (1-5) Saving & Editing Ease(1-5) Easy to learn & use (1-5) Comments (general, more detail to follow) – Med entry little confusing (terms) – Need a way to delete “all” – Unsure about OTC 3.5 3 3 3.25 More of the important data came from the observation and notes. For instance, the survey tool was unable to capture the degree of struggle that people experienced with adding a medication. We also watched people trying to figure out the next logical step. While eventually they figured it out, it seemed that it could be less ambiguous and more direct. Several people asked how to remove a medication, an issue which (due to time constraints) were unable to resolve, but we certainly understand that this is an important issue. For those without a great deal of computer experience, saving and printing were challenging. While the standard dialog boxes appeared for printing and saving, those with less experience had difficulty figuring it out. The users were pleased overall with the idea of the application, and there were not any aspects that they ranked poorly overall. That may be an artifact of the tool, or that this was a group of people that we chose (therefore afraid to be totally honest since we knew them). We observed areas that would need to be addressed were this project to go further. Comments & Prioritization We examined all of the comments that had been recorded and determine that there were about 5-6 that seemed to be common across our sample. A representation of these comments is as follows: 1. “Could you reduce the scrolling? Maybe if you put more on the screen it would help. There seems to be lots of white space available.” 2. “The pill bottle graphic should be bigger” of “there should be a way that the data you need can be highlighted when you get to the blank to fill in.” 3. “How do I remove a med that I recorded by mistake?” 4. “Maybe one of those things like I get when I buy stuff online that shows me how close I am to being down would encourage me.” 5. “The terminology in the add med form is confusing” and “why is certain text red?” 6. “The help text needs to be more specific” We discussed these across the group and assigned almost 5’s (high priority) to all of these. We think this indicates the complexity of created an interface that works for a wide range of users (particularly as related to the elderly). Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 39 Those determined to be of highest priority are question #3 (removing records), #2 (making the med input screens better), and #1 (reduce scrolling). Of these three, we think that number 2 would take the most time, so chances are we would make the easiest and high priority fixes first (1 & 3). Comment #4 (progress icon) is what we consider a “nice to have”, but it is not critical and we think it would take a good deal of time to implement, therefore it has a low importance score and a high effort score. Comment 5 (terminology and font) is moderately important and moderately time-consuming, therefore it was not seen as one with the highest interest – moreover, we believe that this might be fixed with the revision of item #2. Comment 6 (more specific help) is viewed as moderately important and moderately time consuming. Issue # 1 2 3 4 5 6 Importance 5 5 5 2 4 3 Effort to Repair 1 5 4 5 3 3 Conclusion In summary, polypharmacy is defined as the concurrent use of several medications at the same time, and is common problem with older adults because they have to take different medications for different illness they may have. Polypharmacy often results in confusion, error and missed medications. To help to prevent polypharmacy with older adults, we developed “My Med Minder”. “MyMedMinder” is a web based service designed to assist the users in organizing and keeping a history of their medication history and backup their data either digitally or on paper. Our hope of creating “MyMedMinder” as a web interface allows for instant access of these records from any computer with internet access helping to reduce confusion among patients preventing deadly mistakes resulting from wrong drug use. We implemented a web interface similar to our prototype described. The interface had two sections, one was the open site, where browing and information gathering was encouraged. The second part of the interface was the secure area that required a password to access. We developed two access points to the secure area, one for new users which explained the system to them, and the other section was for returning users who had already registered. Once inside the secure area, most of the functionalities to help users prevent polypharmacy could be found. In the first section, we had both a login page and new user registration page. The new user registration page contained a form which takes user personal info and puts it in the database that stores user personal information. The login page contained a form that takes the login name and password and validates it against the database. The information stored in database was designed to store information about each user to allow secure authentication. If successful in logging in, the user is taken to their personal page, where they can find their PHR medication record. On getting to the secure section from a successful login, user has several options including viewing, adding to, and printing their medications records. They can view these by the reason for the medication, the doctor who prescribed the medication, the date medication was prescribed, or by the name of the medication. This allows some degree of internal locus of control – where the user can specify the output in a way that works best Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 40 for them. Also in this section of the system, the user is able to add additional medications as a way of updating the record that may already exist. Some future work possibilities include the creation of a better database structure which will allow for quicker and more customizable retrieval of information. As of now user information and medications are contained in one table. Large flat files encourage redundancy and are can get unwieldy if many users participate in MyMedMinder. Unacceptably long processing and retrieval times could be frustrating for users and difficult to manage. In addition to database structure, in the page that deals with insertion of medications, we would have liked to create an input mechanism that would allow users to insert medications based on illness, who medication was prescribed by, date in which medications was prescribed, and time of the day in which medicine is to be taken. We do have the option for people to extract data in this fashion, but we believe that when people have to enter meds for the first time – where there may be many – that they might want to enter medications in categories. This will require a more advanced database structure There are many changes that may be possible for the interface itself. For example, designing a way that the form fillin for the medication entry could be complete easier (maybe by highlighting the area of the pill bottle image that corresponds with a field mouse over) would be helpful. In addition, some sort of “progress bar” that would show users how they are progressing through the process might be beneficial. There is much work to be done in making the interface more appealing, which given more time, should occur. Finally, we believe that the idea here is a good one and would be of great benefit to patients, providers and society to develop further. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the kind persons (subjects, fellow students, & Ben) who gave us pointers and advice on how to build and then improve this interface. References Barnsteiner, Jane H. (2005). Medication Reconciliation. AJN. http://www.nursingcenter.com Endsley, S., C. Kibbe, D., Linares, A., Colorafi, K. (2006). An Introduction to Personal Health Records. Family Practice Management. www.aafp.org/fpm, 5762 Gleason, Kristine M., Groszek, Jennifer M., Sullivan, Carol, Rooney, Denise, Barnard Cynthia, and Noskin, Gary A.(2004). Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004; 61:1689-95 IHealthrecord.org. Accessed November 3, 2006 at: http://www.ihealthrecord.org/ Kim, Matthew I., Johnson, Kevin B. (2002). Personal Health Records: Evalutation of Functionality and Utiliy. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Assocation. Volume 9, Number 2, 171-180 Medicalert. Accessed September 30, 2006 at: http://www.medicalert.org/E-Health/ Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler 41 Porter, S., Kohane, Z., & Goldman, D. (2005). Parents as Partners in Obtaining the Medication History. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 12(3), 299-305. Putting Prevention Into Practice. Accessed October 15, 2006 at: http://www.ahrq.gov/ppip/50plus/ . Santell, John P., (2004) Reconciliation Failures Lead to Medication Errors. Joint Comission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 32(4), 225-229. Saufl, Nancy M. (2006). Reconciliation of Medications. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 21(2), 126-127. Tang, Paul C. & Lansky, David (2005). The Missing Link: Bridging the Patient– Provider Health Information Gap. Health Affairs. Volume 24, 1290-1295 Tobacman, J., Kissinger, P., Wells, M., Prokuski, J. Hoyer, M., McPherson, P., Wheeler, J., Kron-Chalupa, J., Parsons, C., Weller, P., & Zimmerman, B. (2004). Implementation of personal health records by case managers in a VAMC general medicine clinic. Patient Education and Counseling . 54 (1), 27-33. Tran DT, Zhang X, Stolyar A, Lober WB. (2005) Patient-centered Design for a Personal Health Record System. AMIA 2005 Symposium Proceeding. 1140. Wang, M., Lau, C., Matsen, F., & Kim, Y. (2004). Personal health information management system and its application in referral management. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 8(3), 287-97. Wuerdeman, L., Volk, L., Pizziferri, L., Tsurikova, R., Harris, C., Feygin, R., Epstein, M., Meyers, K., Wald, J., Lansky, D., and Bates, D. (2006). How Accurate is Information that Patients Contribute to their Electronic Health Record? AMIA 2005 Symposium Proceedings. 834-848 Page 42 Appendix 1: Raw Data File; MyMedMinder Opessu, Abbott, & Bassler Age Gender Subject 1 Subject 2 Subject 3 Subject 4 Subject 5 Subject 6 58 27 25 46 22 79 Averages 42.8 1 1 2 2 1 1 42 Years Experience Q1 - AVG "Overall Reaction" # of Meds Q1a 8 7 4 3 6 0.25 2 2 0 4 1 12 4.7 3.5 Q1b 1 3 3 3 3 3 Q1c 3 3 3 5 1 3 Q1d 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 2 3 3 2 3 Q1e 4 3 3 3 3 4 Male = 1 Female = 2 Q2a Q2b 4 3 3 2 3 3 Q2 - AVG "Appearance" Q2c 3 3 3 2 3 1 4 3 4 3 2 5 3 Q3a easy Q3b saving 4 4 3 2 3 2 Q3 - AVG "Save/Edit" Q3c speed 4 4 4 3 3 1 3 3 3 3 3 3 3.1 Q4a 4 4 3 3 3 3 Q4- AVG "Easy to Use" 3.3 Comments (separate file)