affidavits and witness statements in civil proceedings

advertisement

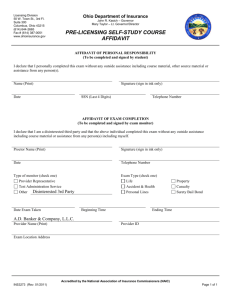

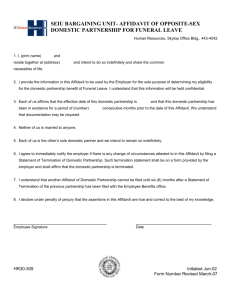

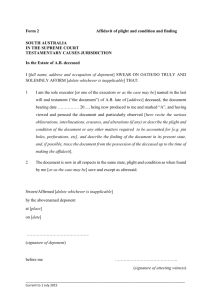

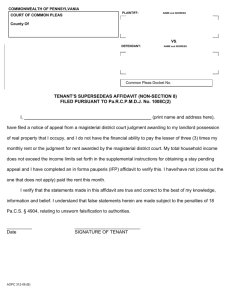

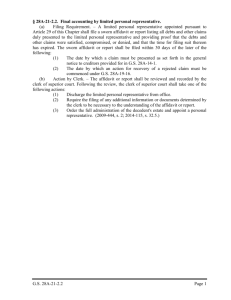

AFFIDAVITS AND WITNESS STATEMENTS IN CIVIL PROCEEDINGS 1. Affidavits were originally unknown to the common law. They were only used in the Court of Chancery and in that Court, the Lord Chancellor would read written depositions taken down before a Chancery official. They are now a common feature of civil proceedings both at an interlocutory level and at trial, particularly in the Supreme and Federal Courts. 2. The justification for the increasing use of affidavits and witness statements is that they facilitate the orderly and efficient disposition of the trial and ensure that a party is not taken by surprise at trial.1 While such a justification reflects a clearly desirable aim in the conduct of litigation, the artificiality of witness statements can sometimes make their use undesirable. Where evidence is controversial and issues of credit may be involved, the intervention of an affidavit (or witness statement) may make it more difficult to unmask the true evidence of a dishonest witness. 3. The cost of drafting witness statements or affidavits for trial may also be prohibitive and unwarranted. Lord Woolf in the Access to Justice report criticised the use of witness statements, stating that:“Witness statements have ceased to be the authentic account of the lay witness; instead they have become an elaborate, costly branch of legal drafting.” (para 55). A. Affidavits Requirements of the Affidavit 4. Affidavits must comply with:(a) The rules of the Court or Tribunal in which they are being filed; (b) The rules of evidence (to the extent that they apply to the relevant form) so that the evidence is admissible. 1 Complete Technology Pty Ltd v. Toshiba (Australia) Pty Ltd (1994) 124 ALR 493 at 498 2 5. The requirements of an affidavit filed in the Supreme, District or Magistrates Court are proscribed by Part 7 of the UCPR. In summary the requirements in relation to the affidavit are as follows:(a) An affidavit must be in the approved form (ie Form 46);2 (b) The affidavit must be made in the first person;3 (c) A note must be written on the affidavit stating the name of the person making it and the name of the party on whose behalf it is filed;4 (d) An affidavit must state the person’s occupation and the person’s residential or business address or place of employment;5 (e) The body of the affidavit must be divided into paragraphs, numbered consecutively, each paragraph being as far as possible confined to a distinct portion of the subject6; (f) Each page of the affidavit must be numbered;7 (g) Documents to be used with and mentioned in the affidavit are exhibits and must comply with the requirements of r.435 UCPR. 6. An affidavit must be sworn before an authorised person pursuant to the Oaths Act 1867. The UCPR imposes additional requirements as to the swearing of an affidavit:(a) In swearing the affidavit the person making an affidavit and the person taking the affidavit must sign each page of the affidavit. The jurat must be placed at the end of body of the affidavit and must 2 3 4 5 6 7 r. 431(1) UCPR (unless it is one of the affidavits which has a specific form such as relating to Wills, or payments into Court). r. 431(3) UCPR r. 431(2) UCPR r. 431(4) UCPR r. 431(4) UCPR r. 431 (6) UCPR 3 contain the matters set out in r.432(3), or if the affidavit is made by two or more persons r.432(4). (b) If there is a question of the person’s ability to read or sign the affidavit the person taking the affidavit must ensure that, the affidavit was read or otherwise communicated to the person making it, that the person seemed to understand the affidavit and the person signified that the person made the affidavit and must certify those maters in or below jurat that that is so, r.433 UCPR; 7. An affidavit which does not comply fully with requirements in the rules may still be filed despite an irregularity in form and may be used with the leave of the Court, r.436 UCPR. 8. The requirements for affidavits in the Federal Court do not differ significantly from the requirements set out above in the UCPR but there are some differences.8 9. As a general rule, the formal requirements of the affidavits will be the responsibility of the solicitor drafting the affidavit. However, Counsel must be cognisant of the formal requirements of the rules not only when settling the affidavit but in preparation for any application where challenge may be made to the admissibility of the affidavit due to its failure to meet the formal requirements of the Rules. 10. It is also important for Counsel to be aware of the formal requirements of an affidavit and ensure that as far as they are able they are met for a more practical reason. Not satisfying the formal requirements of the rules, may distract the Judge from focussing on the real issues in the case. Indeed, Justice John Bryson devoted an article to emphasise the importance of meeting the formal requirements of the Court.9 In his article he stated: “If your documents are inartistic the Judge will be distracted from the process you wish to engage the Judge in, that is, absorbing the relevant evidence, and the Judge’s mind will be led to pathways where 8 9 Order 14 Federal Court Rules Bryson J “Affidavits” (1999) 18 Australian Bar Review 166 4 you do not wish it to go, and to doubts, hesitations and impediments to comprehension produced by the crudity of the attempts to give information.” 11. Counsel should generally ensure that they are not present when an affidavit is sworn to avoid being a potential witness in a case. 12. If you are, as Counsel, involved in the preparation and swearing of an affidavit then you must ensure that the swearing of the affidavit is not a mere formality. This entails ensuring that the deponent has read and understands the contents of the affidavit and that they are swearing to the truth of the contents of that document. 13. While it should not need to be said, a person before whom the affidavit is made must not permit the swearing of an affidavit that he or she knows to be false. 14. This extends to the withholding information that renders an affidavit misleading. If at the time when the affidavit is made, a practitioner has no good reason to suppose that the affidavit is untrue, the practitioner has a duty to the Court to inform the client that the opponent must be told of facts that subsequently come to the knowledge of the practitioner, being facts that show clearly that the original affidavit was untrue. If the client refuses to assent to that course the practitioner should cease to act.10 15. It is not however the duty of a legal practitioner to verify every fact asserted by a prospective deponent. Where a practitioner is dealing directly with a witness in relation to a matter on which the witness could be expected to have complete and accurate knowledge, the practitioner would be entitled to rely on the witness unless there are other circumstances to put the practitioner on notice of enquiry as to the veracity of facts asserted by the witness. 10 Myers v. Elman (1939) 4 All ER 484 5 Is Affidavit Evidence Necessary? 16. Affidavits must be used at trial where proceedings have been commenced by application.11 They are also the form of evidence used in support of interlocutory applications.12 17. If the application is an interlocutory one, an affidavit may contain statements based on information and belief, if the person making it states the sources of the information and the grounds for belief.13 Otherwise, unless the Rules provide otherwise, an affidavit must be confined to the evidence of the person making it could give if giving evidence orally. 18. Counsel will often be required to indicate to instructing solicitors what affidavit material is necessary in support of an interlocutory application and who should be providing the affidavit. 19. This raises an important threshold question as to whether an affidavit is required at all. For instance, in terms of applications to which Part 8 of Chapter 11 UCPR applies where correspondence is exchanged pursuant to r. 444 and r. 445 the Court will generally decide the application on the basis of the contents of the letters between the applicant and the respondent written pursuant to that part which must be filed with the application. 14 The Court may receive affidavit evidence in relation to the application only if the Court directs.15 20. If Counsel is opposing an interlocutory application then a careful assessment needs to be made as to whether or not an affidavit is necessary. It may be possible to successfully oppose an application by pointing out deficiencies in the evidence filed in support of the application without the need to rely on material in opposition. 11 12 13 14 15 r. 390 UCPR r. 26 and r. 28 UCPR r. 430(2) UCPR r. 447 UCPR r. 448(3) UCPR 6 21. It is also necessary to consider who is best to provide the affidavit. 22. At the interlocutory stage it is often advantageous to have a solicitor swear an affidavit on the basis of information and belief rather than a potential witness at trial. This is because is avoids the other party having a sworn account from a potential witness in advance of trial. This can minimise credit issues due to a prior inconsistent statement particularly if one is dealing with an urgent interlocutory application where the witness does not have the benefit of having reviewed all of the discoverable documents or having their evidence seriously tested prior to swearing the affidavit. It is of no benefit to a client to succeed on an interlocutory application only to find that they are discredited at trial due to a hastily drawn. 23. The source of the information and belief must be stated and the same material itself must be admissible.16 Drafting Affidavits 24. While Counsel may generally rely upon Solicitors to draft the affidavits, Counsel may find that in urgent applications or in complex commercial matters where affidavits are being prepared for trial Junior Counsel will be required to draft affidavit material. Even if Counsel does not draft the affidavits, they will generally be required to settle affidavit material for trial. 25. It is important to identify the relevant evidence needed at trial and the witnesses who can provide the affidavit containing that evidence. This is determined by the pleadings and rules of evidence. 26. Prior to drafting or settling an affidavit it is important that Counsel have a detailed knowledge of the discovered documents and to be across the legal and factual issues in the case. Thus Counsel must ensure that the affidavit evidence is framed to either establish factual issues needed to prove the plaintiff’s case or, if Counsel is acting for a defendant, to disprove the 16 The source material must itself be admissible: Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v. Ahern (No. 2) (1988) 2 QdR 158 at 163 and 167. 7 plaintiff’s case and establish the elements of defences which have been raised. 27. The drafting of an affidavit is a finally balanced exercise to ensure that the witness communicates their recollection of relevant events so far as possible in their own words, but where the lawyer needs to ensure that the evidence is presented in an articulate manner which addresses the relevant factual issues. The drafter must avoid the danger of “overdrafting” which results in the affidavit not being an authentic account of a witness’ evidence. 28. An affidavit or statement which is not as far as possible, in the language of the witness, exposes that witness to extensive cross examination which may reveal that a witness does not know the meaning of the words used in their affidavit and ultimately lead to their being disbelieved because the affidavit does not accurately reflect their evidence. 29. When drafting an affidavit the following matters should be taken into account:(a) Evidence should be presented in an orderly manner. A chronological narrative is generally the most favourable although sometimes it may be appropriate to draft it according to the issues of a case. (b) Take full instructions from the client and assess the relevant of the evidence after all the relevant information is obtained; (c) Ordinarily, the witness should tell the whole story in the affidavit as, if material matters are left out, that can be the subject of adverse comment later. That said, inadmissible and irrelevant material should not be included; (d) The witness should understand that the affidavit is his or her affidavit and not a document that belongs to the lawyers. The witness should be asked to ensure that the affidavit reflects that witnesses’ recollection and evidence. It does not forebode well for 8 your case, if a witness in response to why a matter has been included in an affidavit, responds that it is because the lawyers inserted it; (e) Do not have two witnesses present in the room at the time that statement taking occurs. This may lead to challenges later in cross examination as to the independence of the witness’ recollection. If the client is present in the room with a witness ensure sensitive matters are not raised in the presence of a relevant witness and the client; (f) Try and be as accurate as possible without overstating the evidence. If complete accuracy cannot be achieved approximate dates and times may be used. The statement should be put in context in terms of date, place, other people present. It is sometimes useful to make reference to why the witness recollects a particular fact when they do not recollect other events in the same period; (g) Use sub-headings throughout to denote different topics within the witness’ evidence where the affidavits are of some length; (h) Use short paragraphs. Be as concise as circumstances allow and present your evidence in an orderly and readily comprehensible manner; (i) If a term is to be used by a witness throughout the affidavit, define the term at the outset; (j) Make reference to relevant documents which support the evidence being given. If a document is to be exhibited to an affidavit which is to be used at trial, the deponent must be the appropriate person to prove the document being exhibited to the affidavit. Do not in the body of the affidavit recite the content of documents at length. The documents speak for themselves. 9 30. Where an affidavit is confined to facts and does not fall within the exception as to statements made on information and belief, the following further matters need to be kept in mind when preparing an affidavit:(a) Do not include conclusions, but only include the facts themselves (eg describe the factual circumstances leading to a conclusion that the contract existed; an affidavit should simply state “I entered into a contract with Y” unless the fact of the contract is not a matter in issue). (b) Do not include expressions of opinion, or submissions based on facts; (c) Use exhibits where appropriate – a document speaks for itself; (d) Use direct language (eg “I said”, “She said”) as much as possible. Where the precise words cannot be recollected which is often the case then state “I said words to the effect of”; (e) Refrain from expressing beliefs or intentions unless the state of mind of the deponent is directly relevant; (f) Never assert the knowledge or belief of another party; set out the facts which such knowledge or belief may be evidenced or inferred; (g) Ensure that every statement in the affidavit is admissible evidence such that the witness could give the same evidence personally. In this regard it is particularly important to examine closely whether a statement is inadmissible as hearsay as well as the rule against previous consistent statements. Use of Affidavits 31. In order to use an affidavit in a proceeding it must be filed and served unless the leave of the Court is given (r.437 and r.438 UCPR). 32. In order to rely on an affidavit in proceedings one must not simply file it, one must read it before the Court as material upon which you rely. 10 33. If the other side has given you notice that they require the person for examination, the person must be available in Court for cross examination. If however the affidavit has been served on a party less than two days before the hearing, the person who made the affidavit must attend the Court to be available for cross examination unless the party otherwise agrees. 17 The Court may however dispense with the attendance of cross examination of a person making an affidavit and direct that the affidavit be used without the person being cross examined. In the case of the majority of interlocutory applications leave will often be required before a party can cross-examine. 34. As stated above an affidavit must be filed and served before it can be relied upon. However, the mere fact that an affidavit has been filed and served does not require a party to rely upon the affidavit. Until that affidavit has been filed, served and read by the party, the affidavit is not evidence in the proceedings. Once an affidavit has been served on the other party that other party may rely upon the affidavit so served18 to either prove matters in their own case or by using it in cross examination as a previous inconsistent statement. 35. Objections should be made to the affidavits at the time the affidavit is being read or in the case of trial, one should serve the other side with a notice of objection ideally prior to the trial commencing. Objections may be on the basis of relevance or due to non-compliance with the rules of evidence. When an affidavit is read, exhibits to the affidavit, which are referred to in it and comprise part of the affidavit itself, also become evidence in the proceedings, subject to any proper objections and rulings made by the Courts. 36. It is important to explain to the deponent of the affidavit that once he or she is made available to be examined on his or her affidavit, the cross examiner is not limited to the contents of the affidavit. Cross examination may be on any matter relevant to the proceedings, or as to the credit of the witness. 17 18 r. 439 UCPR eg Leaders Shoes (Aust) Pty Ltd v. National Insurance Co of New Zealand Ltd (1968) 1 NSWR 344 at 346. They must read the affidavit first: Re: Margetson v. Jones (1897) 2 Ch 314 at 317 11 This raises a further important consideration in deciding who is to give evidence. If a witness is not critical to establish the factual matters necessary for your case19 give serious consideration as to whether calling that witness may in fact be to the detriment of your case because it may allow the other party to raise matters in cross examination which will assist them to prove their case or damage your own client’s case. B. 37. Witness Statements Subject to directions from the Court, evidence in a proceeding started by application may only be given by affidavit, 20 whereas evidence at trial of proceedings started by claim may only be given orally. 21 In many civil matters commenced by claim, witness statements are generally required to present evidence in chief, rather than witnesses giving evidence orally. Save for the form of the document, there is no material difference between an affidavit prepared for trial and a witness statement. 38. The giving of evidence by way of witness statements is however only permitted if the Court has made such a direction. It is important therefore to consider at the time the directions are being made by the Court for trial whether it is appropriate that the evidence in chief is given in the form of a witness statement. Witness statements are timely and costly exercise and may not be warranted by the nature of the trial. In large complex matters this will generally not be the case and it would generally be to your advantage to have your witness’ evidence in chief set out clearly in a witness statement. If however the trial involves allegations of fraud or misrepresentation or other matters which turn on a witness’ credit it may also be inappropriate to have the evidence in chief in the form of a witness statement. In such a case one may submit that witness statements should not be ordered or alternatively, one may ask the Court to limit the evidence to be given by way of witness statement and order the evidence as to controversial issues should be given viva voce. An alternative direction which has been adopted in some cases 19 20 21 And thus you do not risk a submission being made on the basis of Jones v. Dunkel of an adverse inference being drawn due to the witness’ absence. r. 390(b) UCPR r. 390(a) UCPR; cf s.47 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (C’th) and O.33r.1 FCR 12 are the exchange of a précis of evidence of a witness. While obviously such an alternative is not overly informative, they have the advantage of allowing each party to be aware of the potential evidence being called so as to assist each party in the preparation for trial. 39. The supervised case list practice direction22 contains short form orders with respect to exchange of evidence by way of witness statement. The effect of those orders which provide for exchange of witness statements is that where the party serving the statement at trial calls the intended witness, the party may not, without the leave of the Court lead evidence from the witness if the substance of the evidence is not included in the statement served. Further, a party is prevented from adducing evidence from any witness or witness statements which have not been served in accordance with the requirements of the directions save for the leave of the Court. 40. Generally speaking, a witness statement comes before the Court in the following way:(a) Witness statements are ordered to be exchanged by the Court and sometimes ordered to be filed; (b) The witness is sworn in at the start of his or her evidence; (c) The witness is handed a copy of his or her witness statement and asked to identify it; (d) The witness is asked if the content of the witness statements are true and correct or if he or she wishes to make any amendments to the statement; (e) Counsel will then seek to tender the witness statement; (f) The document will be tendered subject to any objections made by opposing Counsel in relation to the admissibility of the contents of the witness statements; 22 Practice Direction No. 6 of 2000: Annexure B short form orders paras 21-22. 13 (g) Once the admissibility issues have been dealt with the statements will be received as the evidence in chief of that witness and given an exhibit number; (h) The witness will then be cross examined on the contents of the witness statement and generally. 41. The Court will sometimes order statements be provided in reply. Ordinarily, the contents of the witness statement in reply should be contained to matters that the party could not reasonably have foreseen at the time the original witness statements were exchanged. 42. While the Rules do not provide any formal requirements as to witness statements, the formal requirements for court documents which are to be filed in the Registry are set out in Chapter 22 Division 1 of the UCPR and should be complied with. C. 43. Use of Affidavits/Witness Statements in Cross Examination The provision of witness statements or affidavits prior to trial can be of great assistance in preparing for cross examination. Counsel should examine each of the statements or affidavits given to identify whether there is consistency between the various witnesses, to identify any gaps in the evidence of a witness and to identify any inconsistency with contemporaneous documents. Counsel should also review the affidavits or witness statements having an eye to whether they can be used to establish any part of one’s own case. 44. If it is evident that the affidavit or witness statement does not use the language of the witness to being cross examined, it is often an effective cross examination technique to attack the witness by having a witness concede that the affidavit or statement is not in their own words, to lead a submission that the statement or affidavit does not in fact reflect that witness’ evidence but is a lawyer’s document. D. Expert Evidence 14 45. The drafting of witness statements/affidavits to be made by an expert is in a separate category from witnesses of fact. 46. The evidence of an expert is not generally presented in the form of an affidavit or witness statement but is contained in their report. In the Federal Court the expert swears an affidavit swearing that the facts stated in the expert’s expert report are true and that the opinions expressed in the report are opinions held of the witness and exhibits the report. Often, the report is then treated as an affidavit and rulings are made as though its contents were in the form of an affidavit, although such an approach is not technically correct. 47. Expert evidence is addressed in Part 11 of Chapter 11 of the Rules. Rule 427 UCPR provides that an expert may give evidence in a proceeding by a report and that that report is tendered as evidence in chief of the expert. Rule 428 UCPR sets out the requirements for the report. A party intending to rely on the report must, unless the Court otherwise orders, disclose the report, if the plaintiff, within 90 days after the close of pleadings, or if the defendant, within 120 days after the close of pleadings. The exchange of expert reports is often the subject of Court direction. 48. It is important to emphasise to the expert duty of the expert which is set out in r.426 of the UCPR. It provides:- 49. “426(1) A witness giving evidence in a proceeding as an expert has a duty to assist the Court. (2) The duty overrides any obligation the witness may have to any party to the proceeding or to any person who is liable for the expert’s fee or expenses.” In the Federal Court there is a practice direction which must be provided to the experts in proceedings.23 50. The failure to comply with the requirements contained in the Court rules may render the report inadmissible. 23 “Guidelines for Expert Witnesses in Proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia” 15 51. If the expert changes their view in a material way after the report has been disclosed, the expert must as soon as practical, provide a supplementary report stating the change and the reason for it.24 (a) In addition to the requirements in the Court rules, there are rules of evidence, which are peculiar to experts. In order for the evidence of the expert witness to become part of the evidence, the matters which must be established by the evidence are:- (b) The witness must be proved to be an expert in the subject matter of his or her evidence ie they must have, the relevant qualifications and experience which are required to be set out so that the expert is properly equipped to advance the opinion; (c) The witness statement must expose, as exhaustively as practical, the facts and assumptions upon which his or her evidence is based and separate those matters from opinion itself.25 (d) The opinion given by the expert is properly the subject of expert opinion and not a matter upon which the Court could form a view without the assistance of expert evidence;26 52. The expert should not state a conclusion on the ultimate issue at trial which is the province of the Judge or, if relevant, the Jury. Thus, the expert may give an opinion of what a reasonable person operating in the same field would habitually do but not whether in his or her view the defendant was negligent. 53. It is not the role of Counsel to settle an expert’s report. That obviously is not to say that Counsel cannot review the report to ensure that it addresses the relevant issues and documentation in the case and complies with the 24 25 26 r. 429A UCPR and “Guidelines for Expert Witnesses in Proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia”, para 2.8 In this regard, Counsel must always be cognisant of the fact that the facts upon which the report is based must be proved separately at trial. The decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Makita v. Sprowles (2001) 52 NSWLR 705, in which the leading judgment was given by Heyden J, sets out clearly the facts upon which an expert relies to express an opinion must be properly proved. Clarke v. Ryan (1960) 103 CLR 486 16 requirements of the Court in terms of an expert report and expert evidence. But the line must be tread carefully. 54. The dangers of Counsel intervention are highlighted by comments of Brooking J in Phosphate Co-operative Company v. Shears (1989) VR 665 at 681 where he stated:“I think it may be said to be notorious – certainly one’s own experience in commercial litigation supports the view – that the writing of independent experts reports in company cases may be remunerated at a very high rate. There will often be a danger that the client who may well, in addition, be engaging experts who are to act in a partisan capacity, will come to regard the independent expert as another member of a team which is being paid very large sums of money to achieve a certain result. The client will often, as he have at its disposal other advisors who are in a position, by reason of qualifications and experience, to influence, either directly, or indirectly through representations made by the client, the judgment or actions of the independent expert. The greatest circumspection is required in relation to this matter of making representations to an independent expert, not by way of correcting some error of fact, but way of influencing his judgment on the established facts.” 55. Communications between Counsel, Instructing Solicitors and the experts will not always be protected under the clothing of privilege.27 56. Counsel can have an important role in ensuring that the expert selected will provide an independent opinion in accordance with the Court rules. As tempting as it often is for a client to have a hired gun to provide a favourable expert opinion, that opinion will be of little weight or may even be found to be inadmissible if the opinion given by the expert is not regarded as independent. Other Matters 57. If evidence in the affidavit or statement is not in strictly admissible form Counsel should consider whether r.394 UCPR may be taken advantage of where evidence under the rules of evidence would otherwise be inadmissible. 27 Cobram Laundry Services Pty Ltd v. Murray Goulburn Co-Operative Company Limited (2000) VSC 353 cf FAI General Insurance Company Limited v. Interchase Corp Limited (1999) QCA 523; Interchase Corporation Limited (in liq) v. Grosvenor Hill (Queensland) Pty Ltd (No. 1) (1999) 1 QdR 141 17 Rule 394 relevantly provides that if a fact in issue is not seriously in dispute or strict proof of the fact in issue might cause unnecessary or unreasonable expense, delay or inconvenience in a proceeding, the Court may order that evidence of the fact to be given a trial in any way the Court directs. 58. Finally, if the maker of a written statement proves to be unavailable at trial Counsel should examine whether the requirements of s.92 of the Evidence Act 1977 which permits documentary hearsay evidence to be admitted by a Court in civil proceedings are satisfied. Further Reading 1. Paul D. Santamaria and James D. Elliott “Affidavits and Witness Statements Civil Proceedings” The Victoria Bar Compulsory Continuing Legal Eduction Program 2. Downes KE “Drawing an Affidavit Part 1” (2000) 20 Proctor 3. Downes KE “Drawing an Affidavit Part 2” (2000) 22 Proctor 4. John H Karkar QC and Ian G Waller “Admissibility and Taking Objections” 5. Justice Arthur R Emmett “Practical Litigation in the Federal Court of Australia: Affidavits” 6. Justice John Bryson “Affidavits” (1999) Australian Bar Review 18 at 166