The Understanding of Music - Cuyahoga Falls City School District

advertisement

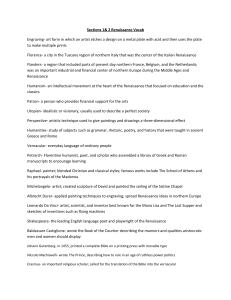

The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes Part 2: Medieval and Renaissance Music Part II slide (slide #1, 2 & 3) We begin our discussion of the historical units with the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Each historical unit first presents the cultural and musical characteristics of the period, followed by chapters on the music and composers. Prelude 2: Middle Ages slide (slide #4) I will divide Prelude 2 into different parts of the lecture to more clearly understand the changes during this very long historical period. The Early Middle Ages refers to a period from the fall of Roman Empire to the end of the Millennium. It is also called the “Medieval period”, referring to an era between the enlightened civilizations of ancient Greece and the Renaissance. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Western society was in a constant state of turmoil known as the “feudal society”. The rule of law ceased to exist and the period was dominated by the conflicts of ‘war lords’ over possessions and property, with very little commerce and no contact between the East and West. Also important was the expansion of Christianity in the tradition of the Roman Catholic Church, who became the first patrons and employers of musicians. It was a very class oriented time divided between the clergy, the nobility, and the peasants, and only the clergy (the monks and the nuns) were literate people who preserved the ancient writings and engaged in scholarly pursuits. Even the legendary ruler Charlemagne bemoaned the fact that he could not read or write – interesting enough because he thought it was a God-given gift, not understanding that it was something one could learn. The art style (there are several examples of paintings in the text) was meant to be symbolic or iconic, and lacked emotion or expression in contrast to the latter Renaissance art style we will study. The Mass (slides #5, 6 & 7) The Mass was and still is the daily worship service of the Roman Catholic faith. The service is divided into 10 parts, five of them collected into what is called the Ordinary of the Mass and the remaining five in the Proper of the Mass. The Proper elements were frequently altered for a variety of purposes, including feaste days of saints, holidays of the church, weddings, funerals or baptisms. The Ordinary of the Mass is never altered, with the text remaining virtually untouched for nearly two thousand years. When we say a composer “wrote a Mass”, we are saying that they composed music to accompany the text for this part of the Mass. Gregorian Chant (slide #9 & 10) 1|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes It should come as no surprise that because the clergy were the literate class that sacred music would be the first style develop a music notation system used in Gregorian chant. We know that the ancient Greeks used music in their dramas and the ancient Psalms were sung, but don’t know what they sounded like because we only have the words. One 6th Century scholar stated – “If a man does not remember the sound of music, they perish forever for they cannot be written down”. Fortunately he was wrong! Gregorian chant is named after Pope Gregory who began the process of collecting the traditional melodies, but it took several centuries to complete this process and arrive at the style of music notation we are studying. You can see on the slide the characteristics of Gregorian chant. We have studied some of these terms, but notice that meter was not yet in use, and the harmony was modal (Church modes), a harmony we will not study in detail. Text settings (slide #11) One characteristic we need to include is the text settings. Syllabic is one note per syllable or word of text as used in the Hallelujah chorus we listened to earlier. Neumatic is 2 to 4 notes per syllable as in parts of the middle section of Hildegard’s Alleluia. Melismatic was probably the most common setting in the beginning of Hildegard’s Alleluia. audio – beginning of Hidegard Hildegard of Bingen (slide #12) Hildegard of Bingen was German, part of the Holy Roman Empire (not to be confused with the original Roman Empire). She was a scholar who studied and wrote manuscripts on many subjects as well as composing music. She founded a convent and is considered a saint. She was the first female granted permission by the Pope to write and teach theology or religious doctrine, a truly noteworthy accomplishment during the 12th century. Hildegard of Bingen listening guide (slide #13) Study this listening guide and listen to Hidegard’s Alleluia. audio – beginning of Hidegard Notre Dame Organum (slide #14) 2|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes With the development of Organum, known as Notre Dame organum because of the influence of composers at the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, western music takes a major step. It is the first polyphonic music and responsible for further refinements in developing pitch and rhythm notation. Perhaps you have heard the old cliché “necessity is the mother of invention”. In this case that is fairly accurate. When the second musical line was added to chant it simply followed the first line at a different pitch level, not too difficult a task to accomplish even if the music is not written down. Gradually the second, third and eventually fourth lines became independent melodies with different rhythm and pitch movement and therefore, a more precise system of rhythm & pitch notation were required to keep all of the parts together. Although composers in this period did not normally autograph their work, we are fairly certain who wrote the music because Leonin, the first composer wrote only two part music and Perotin, known as ‘Perotin the Great’ added the third and fourth lines of music. Notre Dame Cathedral (slide #15) Notre Dame School listening guide (slide #16) Study the listening guide and listen to Notre Dame School Organum. Notice that the first section is a long sustained note melody in the bottom part (almost like a drone), while the two upper voices are very rhythmical. Also notice that the piece ends with a simple monophonic chant melody. Here’s an important clue for you – on the exam, I will only play the first section because that is the polyphonic style known as Organum. Audio - beginning of Notre Dame Organum Prelude 2: Late Middle Ages (slide #17 & 18) In the late middle ages (the last few centuries), Western society is undergoing dramatic changes. The dominance of war loads in the feudal society was coming to a close. With the fragmenting of the Holy Roman Empire, powerful nation/states are beginning to emerge. These emerging royal courts became the second source of musical “patronage” or employment for musicians. There was an increase in cultural exchange, the result of expanded commerce and trade between the East and West, the Crusades, and the activity of explorers. Cities became centers for education, arts, & culture. Learning accelerated in the monasteries and convents, and the first universities since Plato’s Academy in ancient Greece were started in Bologna, Italy & Paris, France. To illustrate the importance of such institutions of higher learning, the destruction of the ancient Alexandrian library which contained 400,000 volumes would not be replicated for nearly 2,000 years, and by the 14th century, there were 500 monasteries in England alone. Secular Music in the Middle Ages (slide #19 & 20) 3|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes With the rising power of the royal courts, it should not be a surprise that secular music becomes more important. After all, the kings, queens, and emperors are always in need of music for their ceremonies, celebrations, and entertainment. This secular music was performed by a variety of entertainers depending on the area of Western Europe we examine. The only one mentioned here are the “troubadours” from southern France, but there were others such trouveres in northern France, the minnesingers in Germany, or the wandering minstrels known as jongleurs & golliards were defrocked monks. Some of these entertainers were not only musicians, but also read poetry, or engaged in juggling, acrobatics, and dance, and some entertainers were themselves royalty (such as Richard-the Lionhearted in England). The latter part of the middle ages is known as the Ars Nova meaning ‘new art’, which applies not only to music, but also to changes in literature (Dante’s Divine Comedy, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales), and architecture moving from the Romanesque style to the imposing Gothic cathedrals. Mauchaut (slide #21) Our example of late Middle Ages music is the French composer, Machaut. As was now common, he was employed by both the royal courts, notably - Charles, Duke of Normandy who would become king of France, and also by the church - the Cathedral of Rheims in France. Thus, Machaut composed both sacred and secular music. One notable work we will not study is the famous “Notre Dame Mass”, the first polyphonic setting of a Mass. Our example is a “Chanson”, which is French for ‘Song’. Machaut: Puis qu’en oubli (slide #22 & 23) Study the listening guide and listen to Machaut’s Since I am Forgotten. Notice the mournful sound, appropriate for a song about the neglect of a beloved friend. 4|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes Prelude #2 Renaissance (slide #24 & 25) The Renaissance is a crucial period in Western culture. Your textbook describes is as the “passing of European society from an exclusively religious orientation to a more secular one, and from an age of unquestioning faith to one of belief in reason & scientific inquiry”. It has been described by other historians as the “awakening of intellectual awareness” and the “birth of the modern era”. Certainly, these developments were gradual and not in a specific year, but the Renaissance is usually connected with the destruction of Constantinople (the ancient Byzantine culture) in 1453, and the fleeing of scholars and artists to the West. They first settled in what is now Italy, a place of great wealth, opportunity, and influence in the 15th century. Two of the primary characteristics included becoming a more “secular” culture, and the philosophy known as “humanism”. It generally refers to the idea that we are focused on the present rather than the afterlife, that we are capable of ethical conduct, social justice, self-fulfillment, and progress by the powers of own observations and reasoning instead of relying on traditional authority and the church. Indeed, in modern discourses we hear the term “Secular Humanism” one idea presented in contrast to the “religious beliefs. This time was inspired by the ancient Greek cultures. Just think of the cliché known as the “Renaissance man”. It implies an individual who is well-rounded, and possesses knowledge and skills in all of the arts and sciences, a common characteristic that also existed in ancient Greece. Thus we have painters or sculptors who are also inventors, scientists, and authors. Prelude #2: Renaissance (slide #26) This period was an age that changed mankind’s view of the world and our place in the grand scheme of creation. With the invention of the magnetic compass, exploration expanded and proved that the earth was not flat, and science provided knowledge of the entire solar system and universe, that the sun did not revolve around the earth. The invention of the “printing press” was probably the single most important development in the history of music. Not only did it advance knowledge & learning in general through the availability of books, but the printing press turned music into a common experience of everyday life. Consider this – previously to this invention, if you wanted to study music, you would have to borrow my music, and then have been trained in the skill of music writing to create your own copy (a very limited skill possessed by only a few individuals). Within 50 years after inventing the printing press, there were 400,000 printed copies of music all over Western Europe. This spread the study and performance of music into the home life and developed an entire new demographic for music – the ‘amateur’ musician learning and performing music for simple pleasure. There was a corresponding growth of music schools, publishing houses, civic ensembles, which would eventually provide new employment for 5|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes musicians. The style of art and music also changed. The art (painting, sculpture) was now becoming realistic, and expressive. Faces and poses in painting have a sense of emotion and drama (as opposed to the blank stare of medieval art). Sculpture now included the human nude, which had been banned for 1000 years, but was common in ancient Greece. Music was now viewed as an “expressive” art form. In the 12th, St. Augustine had noted this effect, stating that “music has the power to uplift the spirit, but it could also seduce the listener into easy pleasure”. In the ancient world, music was studied, but mostly because of its moral implications, or mathematical qualities. Indeed, the original 7 liberal arts and sciences of ancient Greece grouped music with Arithmetic, Geometry, and Astronomy. But in the Renaissance period, musicians understood that the real significance of music was expression, to express an emotion or idea. Comparison Middle Ages/Renaissance (slide #27) Before we begin to study the music and composers of the Renaissance, examine the first 2 columns of this chart on page 103 of your textbook. Renaissance Sacred Music (slide #28 & 29) You will notice that all of our assigned vocal music is without instrumental accompaniment. That is appropriate because the Renaissance is considered the “Golden Age of a-cappella” singing. By this time in history, imitative polyphonic texture is the dominant style, but other textures are also included at times. In sacred music, some of the new polyphonic works are based on a pre-existing melody called the “cantus firmus”. The harmony is still “modal” as it was in the Middle Ages (a harmony we will not study in detail). But it did increasingly have sections with fuller chords. Josquin (slide #30) Josquin de Prez, known as Josquin, was from France. He was Franco-Flemish, a culture that inhabited present day Belgium, and northern France, also known as Flanders, and a region with a thriving musical establishment referred to as the “Netherlands School of Music”. When he became well-known, he moved to the location with the most opportunity, the highest paying and most prestigious positions in his day, which was modern day Italy. His employment included composing for both royal courts and the prestigious “Papal Choir” in Rome. The textbook cites Josquin as an example of the new “humanist” style in music. Late in life, he returned to his homeland of France. Although he composed both sacred and secular music, his most important contributions are Motets. 6|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes Motets (slide #31) The motet is the most important genre of early polyphonic sacred music. It is “acappella” (without instruments). Josquin, Ave Maria listening guide, pg. 1 (slide #32) Josquin’s motet, Ave Maria, is written for the standard 4-voice choir – soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Much of it is imitation of individual voices, with other sections involving imitation of pairs of voices, and some sections using homorhythmic texture. Josquin, Ave Maria listening guide, pg. 2 (slide #33) Here is an example of the beginning section, imitating the melody from Soprano (the highest voice) to Bass (the lowest voice). audio example - Josquin Here is an example from a section with pairs of voices in imitation. audio example - Josquin Here is an example from the homorhythmic section in a different meter. audio example - Josquin After that section, the piece returns to the imitation style. Most of this piece is imitative and very similar, but listen to the very ending. audio example - Josquin Obviously, this is a VERY different rhythm and feel. The first thing you should ask yourself when you hear a dramatic change in style is WHY. Most good composers, regardless of whether it is classical, movie sound tracks, Broadway, or popular music will change the style for an EXPRESSIVE purpose, not simply to show you their skills or to keep you from becoming bored. That being said, what is this style change about? When we read the text, we discover this is a piece of praise – Hail Mary - example of grace, example of humility, example of purity, and so on. BUT, the last sentence is not about praise – it is a personal prayer – it is remember me, be with me, help me. That is an important example of the way Renaissance composers used musical characteristics to create an expressive musical style. 7|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes The Reformation and Counter-Reformation (slide #34) Two important events concerning sacred music were the Reformation and CounterReformation. The so-called “Protestant” Reformation involved many individuals including Calvin in Switzerland, Knox in Scotland, and others – but most importantly Martin Luther in Germany, who nailed his “95 Thesis” to the door a church. Certainly, they were most concerned with changing the doctrine and liturgy of Roman Catholic Church, but the end result was the many Protestant denominations we know today such as Lutherans, Presbyterians, Anglicans, Methodists, etc. Our interest is in the musical changes they promoted. They wanted the text in the common language of the people (or the Vernacular) instead of traditional Latin. They wanted the congregation more involved in the music of the worship service, which prompted an emphasis on hymn tunes – simple melodies that even an un-trained person can easily learn and remember. In Martin Luther’s Germany, these hymns are called “Chorales”, which we will study in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. These changes and others such as bringing instruments and secular music into the worship service were not acceptable to the Roman Catholic Church. They gathered the Bishops and Cardinals at a place called Trent. The Council of Trent decreed an end to the so-called “Reforms” and that sacred music should be strictly “a-cappella” (with no instruments). One critic of the reforms stated “Whence hath the Church so many Organs and Musical Instruments? To what purpose, I pray you, is that terrible blowing of the bellows, expressing rather the crack of thunder than the sweetness of the Voyce”. The council also demanded that church music remain in the traditional Latin, involve no secular influences, and focus on the “clarity of the text”. Because some textures seemed too complicated, causing confusion of the message, they even considered outlawing all styles except simple monophonic melody, but fortunately they did not do that. Palestrina is generally regarded as the example of writing sacred music in a style that was acceptable to the Roman Catholic Church Council of Trent. Palestrina (slide #35) Palestrina was born in a small village close to Rome. During his career, he held the most prestigious musical position in Europe, at St. Peter’s Basilica. In other words, he worked for the Pope. He did write some secular music, but his most notable achievement is writing sacred music according to the Council of Trent guidelines. It is claimed that his final job was re-writing all of the liturgical music for the Roman Catholic Church during the late Renaissance. Some historians have even proclaimed him the “Savior of Church Music”. Palestrina’s style results in a choir sound that is simply magnificent. It is acappella, but it is very full and rich because he usually uses 5 or 6 parts instead of the standard 4 parts. Notice in the example we study where the extra parts are added. It is not in the high range, but includes 2 Tenor parts, and 2 Bass parts which add great 8|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes depth and fullness of sound. His choral writing has been a model for composers regardless of whether they are composing secular or sacred music. Palestrina, Pope Marcellus Mass, Gloria (slide #36 & 37) Study the listening guide and listen to Palestrina’s Gloria from the Pope Marcellus Mass. Audio – Palestrina Mass Renaissance Secular Music (slides 38 & 39) As we have discussed, the rise of secular music was due in large part to the entertainment needs of the royal courts, or music at civic occasions. Secular music was also popular with the new class of “amateur” musicians and as entertainment in the home. The two most common forms, whether court, civic, or home were dances and songs. The Chanson we have studied earlier as an example of a song. In this section we will study the Madrigal. The Italian Madrigal (slide #40) The Madrigal was started in Italy. In some historical periods, it could be sacred music but the Renaissance madrigal is a secular poem set to music originally as aristocratic entertainment and sung by a quartet of solo voices. The most important expressive device is called “Word Painting”. Word Painting Examples (slide #41) Listen to a few “word painting” examples in this Monteverdi madrigal. “The breeze laughs about” – notice how the rhythm and ascending sequence imitates laughter. (audio example Monteverdi) “The sea becomes calm” (audio example Monteverdi) “The sky becomes radiant” - notice the constant use of high note entrances to imitate bursts of radiant light. (audio example Monteverdi) To this point, the poem is about the scene of a story. The next section which begins “I alone and sad and weeping” now becomes a personal story. Notice how the music has changed to a slower, more serious, and even tormented style. (audio example Monteverdi) 9|Page The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes The English Madrigal (slide #42) The English Madrigal retains all of the general madrigal characteristics, but is a much lighter, cheerful story and sound that often includes the non-sense syllables such as “fala-la-la” inserted just for the joy of singing. We will hear the word painting examples in a moment. Farmer (slide #43) Our English madrigal example is by John Farmer, who worked in Ireland and England. The piece we are studying is called “Fair Phyllis”. Fair Phyllis listening guide (slide #44) Here are examples of “word painting” in the music. “Fair Phyllis I saw sitting all alone” – because of using the word “alone”, the words are sung by a solo voice audio example - Farmer “Feeding her flock near to the mountain side” – because of the word “flock” implying many, the words are sung by the entire quartet audio example - Farmer audio repeat of both sections togethe) “Up and down he wandered” – the melody uses many imitations of a short descending motive on the words “up and down” audio example - Farmer Susato: Three Dances (slide #45) Instrumental secular music during the Renaissance also included a variety of dances. Susato is a Belgium composer, and our example is a set of 3 dances, each one in Binary form, performed without interruption. The recording uses period instruments, which have a much harsher sound that the modern improved instruments we are studying. It is a “wind band” without strings. Susato Listening Guide (slide #46 & 47) 10 | P a g e The Understanding of Music Unit 1: Middle Ages & Renaissance – Lecture Notes When listening to this music, you should envision a very stately court style of dancing with each person dressed up in their finest gowns and attire. The dance would have been performed in a circle with couples moving towards the center and back, or in 2 lines with couples moving the length of the formation in between the lines. The dancing would always be at arms-length (none of this close dancing in today’s style), and of course involve the obligatory bow throughout especially at the beginning and end. 11 | P a g e