hw2

advertisement

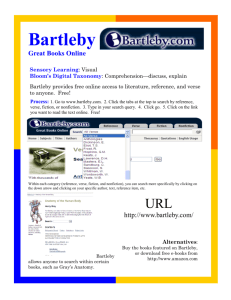

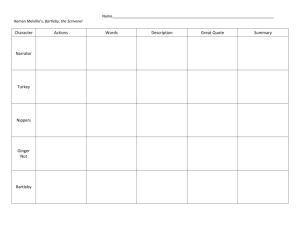

Bobbi Parry HW 2 Book-based Digital Library I selected Bartleby.com for my examination of a book based digital library. Bartleby.com is an entirely online, ad-based digital library of non-copyrighted materials, including reference works like the CIA World Factbook and Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, as well as classic works of fiction, poetry and non-fiction. The site takes its name from Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivner, a scribe who refuses to do any work. Bartleby.com was created in 1993 by Steven H. van Leeuwen as a private, online collection of classic literature, first publishing Walt Witman’s Leaves of Grass. In 1999, it was incorporated into Bartleby.com, the entity it is today (Bartleby.com Welcome page). I am not as familiar with text-based digital libraries, I also consulted Project Gutenberg, another online collection, a fair amount, to get some perspective on what a digital library might consist of. As William Arms notes in Digital Libraries, digital books and paper books have different advantages, and each are useful in different contexts: “Each has strengths the other cannot approach. Computing allows powerful searching, which no manual system can provide. The "human factors" of a printed book are superb: it is portable, it can be annotated, it can be read anywhere, it can be spread out on a desktop or carried in one hand; no special equipment is needed to read it” (165). In this examination, I wanted to understand how book based digital libraries worked to meet the needs of their users. Homepage layout Bartleby.com’s home page (Fig. one) looks more like a commercial website than many other digital libraries, primarily because of its advertising content, but also because of its layout, which includes Featured Authors (oddly, The Holy Bible and Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, neither of which is an actual author), and its lack of instruction on the use of the site. By contrast, Project Gutenberg’s homepage features instruction on how to download items, information on copyright within and without the United States and two search boxes in the lefthand column (Fig. two). Some difference between the two sites is to be expected because Bartleby doesn’t offer a downloading feature (which I’ll discuss later) but Bartleby does seem to have more of an emphasis on immediate access to content. 1 (Fig. one) (Fig. two) Bartleby offers multiple access points for any user looking to get started. Several collections are featured on the front page, primarily in the form of a Featured Author graphic that allows a user to enter that specific collection. A search box at the top of the page allows users to 2 search specific collections. Above that, four tabs allow users to browse based up on form. Dropdown menus labeled with the same options are featured on the right-hand side of the screen, as is an A-Z index of all the titles, authors and subjects on the site (Fig. three). In short, Bartleby provides a wide array of options to users looking to access their materials, but not much guidance on which might provide the best results. (Fig. three) Also interesting to note is that Bartleby features an online store, where users who locate works they’re interested in purchasing can go to buy paper copies of the books they view on the site. Clicking on the cover of the book displayed in the bookstore takes the user to the amazon.com page featuring the book. Browsing capabilities Bartleby.com is primarily organized by type of literature—fiction (including plays), nonfiction, poetry, and reference. Beyond that basic organizational structure, most works are located by title or author—minimal subject categorization is given, and is exclusively for reference works. Dates, nationalities, literary genres and other potential categorization tools are not used for organization or searching, meaning that browsing may involve a lot of rifling through works put together alphabetically. On the homepage, each of the tabs at the top takes the user to a list of all the works available under that heading, categorized by form, and then listed in alphabetical order (Fig. four). The user can then decide which work he or she would like to browse and double click on its title. 3 ( Fig. four) The list of works in each category is impressively long, and fairly wide ranging. The Reference tab contained links to both the The World’s Famous Orations, as compiled by William Jennings Bryant, and Fannie Mae Farmer’s The Boston Cooking School Cookbook. Works are listed by author and title—a click on the author takes the user to an index of all his or her work, along with a search box that allows the user to search for phrase or topic. Certain entries also contain documents concerning the author, ie Tom Paine’s entry also contains a selection from the Caimbridge History of English Literature. Unfortunately, this is not entirely consistent across the listings—some authors aren’t linked (I assume this means they only have one title associated with their name, although other authors that are linked only bring up one title when they’re clicked on) and others are listed strangely (The Bible is listed as the author of The King James Version). If a specific work is selected the user brings up another screen offering users the option of accessing the work via table of contents, or as appropriate other options, such as an index of first lines for poetry. Each work is provided with a bibliographic record, which frequently states not only original author and publication information, but also information concerning the source of this particular version of the work, such as The Harvard Classics. This helps mitigate another quirk of the site, which is that the publication date of the work is given as the year the book it’s contained in was published. This works well for books like Fannie Farmer’s cookbook, written in the early 20th century, but makes the publication dates for the Bible (1999) (Fig. four) and the correspondence of Pliny the Elder (1909-1914) a little confusing. (Fig. five) Once a user is in the site, links to the indexes of subjects, titles and authors are provided in the main header bar, as are links to thesauri, books of quotations and English usage also included on the site. This is a neat feature, made slightly strange by the fact that the majority of 4 the works featured on the site are at least 100 years old, meaning using them as actual reference material instead of historical documents (reference use is why I presume they’re presented there) seems a little strange. Conveniently, once a work has been selected, its title automatically appears in the search bar at the top of the screen, making it easier to search within the work. Document viewing Every document on Bartleby.com is only viewable via HTML, within the browser, embedded as part of the basic webpage. Nothing is downloadable (although cutting and pasting is, of course an option). The advantage of this the speed of the site, which allows access to the material from any computer, as quickly as the web connection and internet browser allow. Arms, discussing different ways of displaying documents in digital libraries, states that HTML has evolved since its inception to allow designers to control formatting of documents (175). Even if it lacks the total flexibility of a mark-up language like SGML, it still allows the designer to provide a basic structure to the document, allowing it to be both readable and searchable by its users. Arms gives the appearance of a document equal weight to its structure. Appearance and structure “should not be seen as alternatives or competitors, but as twin needs, both of which deserve attention. In some applications a single representation serves both purposes, but many digital libraries are storing two versions of each document” (185). Bartleby is not among those offering two versions, although much of this may be because it functions primarily as quick and easy access to a variety of works, not as a mechanism for preservation or even long term usage. To this end, Bartleby.com seems intent on giving users much the same viewing experience they would receive if they were viewing the work on the printed page. Front matter and other information that would be included at the beginning of a paper text are all there and included with the body of the work in a table of contents, all of which comes in the form of hyperlinks to allow the user to navigate through the document easily, effectively as if they were flipping through a book. The appearance of the text on the page is very no-frills, just the text itself, and occasionally the picture of an author. Relevant illustrations will be displayed, if the work demands it. For example Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives contains scanned in copies of the original illustrations, placed in the browser with the text. In the case of Gray’s Anatomy, a work known largely for its detailed engravings, illustrations can display larger in a new browser window if a user clicks on them (Fig 6a and 6b). It also contains links to images within the page, so users can click to the as it’s referenced in the text. Footnotes also work as hypertext, allowing the user to easily move back and forth between page and notes. Source publication information is given, no image of the document within its original source given, something which, depending upon the age and nature of the document may be relevant, or at least interesting to see. 5 (Fig. 6a) (Fig. 6b) I decided to compare side by side how documents displayed in Project Gutenberg and in Bartleby.com, just to get an understanding of the two systems. Project Gutenberg offers scanned in copies of non-copyrighted work, and allows users to either view the work within their browser 6 or download it in a variety of formats, usually HTML and plain text, from either the main site, a mirror site or a peer to peer site (Fig seven). (Fig. seven) To compare the way the two sites displayed documents, I looked at the same Emily Dickinson poem using both collections. Of course the Bartleby poem displayed within the browser window (Fig. eight); the Project Gutenberg version offered a variety of different versions available for download. Both the plain text version displayed within a new browser window; the zip file downloaded to the computer, but both displayed the same text version of the poem (Fig. nine). Users can also choose the plain text version of Gutenberg and the Bartleby poem displayed with almost equal speed, although the Gutenberg version did contain more front matter. It also contained Dickinson’s original hyphenation, something the Bartleby’s version did not (although this may be a result of the source material used). Bartleby’s did contain line numbers, as all their documents do. Both the plain text and zip versions of the Gutenberg document scrolled down as a single page, no matter the length of the work, while the in-browser viewing of Bartleby and the Gutenberg allow the user to flip between “pages,” more closely mimicking the reading experience while also making navigation a great deal easier. 7 (Fig. eight) 8 (Fig. nine) Searching capabilities In Michael Lesks’s Understanding Digital Libraries, the author outlines some of the necessary components of a good online search—a good understanding of search vocabulary, the nature of the usage of connectives, and the display of the items retrieved (38). However, a search on Bartleby.com provides the user with little opportunity to utilize any of these techniques. Every search is a full text search with no clue as to what other applicable terms may exist, other than the exact phrase the user is looking for. There is no capacity for Boolean operators or any other connectors, and while items are displayed in order of relevance, that is occasionally difficult to determine. There is only one way to conduct a pure search from the homepage of Bartleby, and that is to select from the dropdown menu attached to the search box at the top of the screen. This menu contains both titles of individual works from the site as well as options to search All Verse, or All Non-fiction. To conduct an experimental search, I selected Gertrude Stein from the dropdown menu and entered the term “houses.” I received three hits, all from the works of 9 Gertrude Stein, each containing the word “houses” in the text. Other searches I conducted acted much the same way—a search for “population France” in the CIA World Fact Book brought up several entries, all containing the words population and France. A user searching for the actual population of France would have to determine which entry actually concerned the nation of France (not too difficult, since it was the first hit) and then scroll down in order to find the portion of the document that listed population. Searches for specific lines of poetry proved less successful. A search for “shall I compare thee to” in All Verse brought up hits from three different collections of Shakespeare’s sonnets held on the site, as well as hits from other poems containing the terms “thee” and “compare.” (Fig. ten) Limiting the terms with quotations narrowed the search results to just the Shakespearean sonnets. Despite the limitations of the simple all-text search, it is still effective when trying to research a single line of poetry, something I discovered when trying to look for the same thing in Project Gutenberg. (Fig. ten) Bartleby also offers inter-text searching, which allows a user who has located the proper document to then find a single line or phrase within the document that matches, although the results display in the same manner as other searches, which means the search only takes you within the same page, or chapter of a document, instead of to the exact match. Evaluation and Conclusion I had the feeling when I started to look at Bartleby.com that it was a site designed for quick and easy access to information. As I was examined it, I was impressed with the range of content available, and the ease with which a user who knew what they were looking for could 10 locate something. While the no-frills approach to appearance didn’t add much to my viewing experience, it also allowed me to access the site from several different computers with different browsers (even different versions of different browsers) with no trouble loading or formatting. I was however, quite disappointed in the search capabilities of the site, as they don’t seem to have been updated in quite a while. It seems that any site specializing in out of copyright literature should allow users to search by date, and site that deals in literature should provide basic subject categorizations. I also found the some of the cataloging issues on the site, like publication dates, to be confusing and poorly thought out. All in all, I found the comparison between Project Gutenberg and Bartleby.com to be very interesting. Although I did find Project Gutenberg to be generally superior, I also thought that many of the problems with Bartleby.com were instructive of the pitfalls along the path of designing an effective and well thought out digital library. 11 Works Cited Arms, William (2000) Digital Libraries Morgan Kaufman: Amsterdam (accessed via Netlibrary, 2/23/2010) Bartleby.com (2010) www.bartleby.com (accessed 2/23/2010) Lesk, Michael (2000) Understanding Digital Libraries Morgan Kaufman: San Francisco (accessed via Netlibrary, 2/23/2010) Project Gutenberg (2009) www.gutenberg.org (accessed 2/23/2010) 12