The Mask and Mirror

advertisement

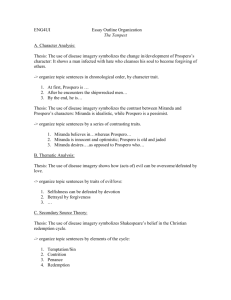

The Mask and Mirror The Mask and Mirror Studio album by Loreena McKennitt Released 1994 Genre Folk, World music Length 52:46 Quinlan Road Label Warner Bros. Records 45420 Producer Loreena McKennitt Loreena McKennitt chronology The Visit (1991) The Mask and Live in San Mirror Francisco (1994) (1995) The Mask and Mirror is an album by Loreena McKennitt released in 1994. The album is certified Gold in the US[ Track listing 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. "The Mystic's Dream" – 7:40 "The Bonny Swans" – 7:18 "The Dark Night of the Soul" – 6:44 "Marrakesh Night Market" – 6:30 "Full Circle" – 5:57 "Santiago" – 5:58 "Cé Hé Mise le Ulaingt?/The Two Trees" – 9:06 "Prospero's Speech" – 3:23 Song information "The Mystic's Dream" was featured in the 2001 miniseries, The Mists of Avalon, as well as the 1995 film Jade. "The Bonny Swans" has been made into a video. "The Dark Night of the Soul" is based on the poem "Dark Night of the Soul"[1] by St. John of the Cross. "Santiago" is named after the Spanish city Santiago de Compostela and by the saint that carries its name. "The Two Trees" takes its lyrics from a poem by William Butler Yeats. "Prospero's Speech" is the final soliloquy and epilogue by Prospero in William Shakespeare's play The Tempest. "Marrakesh Night Market" has been covered by Greek singer Kalliopi Vetta in her album Sto Phos. The Mists of Avalon is a 2001 miniseries based on the novel of the same name by Marion Zimmer Bradley. It was produced by American cable channel TNT and directed by Uli Edel. The miniseries "was watched by more than 30 million unduplicated viewers" during its premiere; the first episode "was the highest-rated original movie of the summer on basic cable."[ Dark Night of the Soul Jump to: navigation, search For the album, see Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse Present: Dark Night of the Soul. Dark night of the soul is a metaphor used to describe a phase in a person's spiritual life, marked by a sense of loneliness and desolation. It is referenced by spiritual traditions throughout the world, but in particular by Christianity. Poem and treatise by Saint John of the Cross Dark Night of the Soul Spanish: La noche oscura del alma) is the title of a poem written by 16th century Spanish poet and Roman Catholic mystic Saint John of the Cross, as well as of a treatise he wrote later, commenting on the poem. Saint John of the Cross was a Carmelite priest. His poem narrates the journey of the soul from her bodily home to its union with God. The journey occurs during the night, which represents the hardships and difficulties the soul meets in detachment from the world and reaching the light of the union with the Creator. There are several steps in this night, which are related in successive stanzas. The main idea of the poem can be seen as the painful experience that people endure as they seek to grow in spiritual maturity and union with God. The poem is divided into two books that reflect the two phases of the dark night. The first is a purification of the senses. The second and more intense of the two stages is that of the purification of the spirit, which is the less common of the two. Dark Night of the Soul further describes the ten steps on the ladder of mystical love, previously described by Saint Thomas Aquinas and in part by Aristotle. The text was written while John of the Cross was imprisoned by his Carmelite brothers, who opposed his reformations to the Order.The treatise, written later, is a theological commentary on the poem, explaining its meaning by stanza. Spiritual term in the Christian tradition The term "dark night (of the soul)" is used in Christianity for a spiritual crisis in a journey towards union with God, like that described by Saint John of the Cross. Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, a 19th-century French Carmelite, underwent similar experience. Centering on doubts about the afterlife, she reportedly told her fellow nuns, "If you only knew what darkness I am plunged into."[1] While this crisis is presumed to be temporary in nature, it may be extended. The "dark night" of Saint Paul of the Cross in the 18th century lasted 45 years, from which he ultimately recovered. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, according to letters released in 2007, "may be the most extensive such case on record", lasting from 1948 almost up until her death in 1997, with only brief interludes of relief between.[2] Franciscan Friar Father Benedict Groeschel, a friend of Mother Teresa for a large part of her life, claims that "the darkness left" towards the end of her life. Typically for a believer in the dark night of the soul, spiritual disciplines (such as prayer and consistent devotion to God) suddenly seem to lose all their experiential value; traditional prayer extremely difficult and unrewarding for an extended period of time during this "dark night." The individual may feel as though God has suddenly abandoned them or that his or her prayer life has collapsed. But given that a true case of the dark night of the soul is a volitional act of God, it cannot truly result in atheism or total loss of belief since it is contrary to the nature of God's desire to invite people to Him. What must be said however is that in this period, a believer may have 'heterodox' feelings toward God, grow angry with Him, or question His nature. It is important to note however that the presence of doubt is not tantamount to abandonment -- there is strongly Biblical tradition of authentic confusion before God (Psalms 13, 22, and 34 display King David, the 'man after God's own heart' undergoing serious confusion and anguish at God, yet this is not condemned or mentioned as unfaithful, but rather the only measure of faith that David could have in the face of such withering abandonment). Rather than resulting in devastation, however, the dark night is perceived by mystics and others to be a blessing in disguise, whereby the individual is stripped (in the dark night of the senses) of the spiritual ecstasy associated with acts of virtue. Although the individual may for a time seem to outwardly decline in their practices of virtue, they in reality become more virtuous, as they are being virtuous less for the spiritual rewards (ecstasies in the cases of the first night) obtained and more out of a true love for God. It is this purgatory, a purgation of the soul, that brings purity and union with God. For the most complete modern explanation of the dark night of the soul is provided by Richard Foster in Chapter 2 - Prayer of the Forsaken in well-known work, "Prayer: Finding the Heart's True Home." Buddhist parallels In Buddhist vipassana meditation, the practitioner passes through the "Sixteen Stages of Insight" (nanas)[5][6] towards Awakening. Steps five to ten are the "Knowledges of Suffering" (dukkha nanas): Knowledge Knowledge Knowledge Knowledge Knowledge Knowledge of of of of of of Dissolution (bhanga nana) Fearfulness (bhaya nana) Misery (adinava nana) Disgust (nibbida nana) Desire for Deliverance (muncitukamayata nana) Re-observation (patisankha nana) Western Buddhist meditators and teachers regularly compare this experience to the Dark Night, for example Jack Engler[7]: The 16th century Christian contemplative, St. John of the Cross, called this phase "the dark night of the soul" for the same reason: the night is dark because it is overwhelmingly clear that neither God nor the soul nor the self as we knew them are any longer to be found. There is instinctive recoil and withdrawal: nothing seems sufficiently worth doing or caring about without them. These parallel experiences across faiths have led to speculation that the Dark Night is a common mystical state or stage which is independent of the specific belief system. The Buddhist author Daniel Ingram, who also invokes St. John, uses the term "maps" for the sequence of mental states[8]: The Christian maps, the Sufi maps, the Buddhist maps of the Tibetans and the Theravada, and the maps of the Khabbalists and Hindus are all remarkably consistent in their fundamentals. (…) These maps, Buddhist or otherwise, are talking about something inherent in how our minds progress in fundamental wisdom that has little to do with any tradition and lots to do with the mysteries of the human mind and body. Note that not all variants of Buddhism recognize these stages. Islamic parallels For more details on this topic, see Miguel Asín Palacios#John of the Cross. Islamic sources for this account of the dark night of the soul have been suggested by Miguel Asín Palacios[9] and developed by others,[10] who suggests that Ibn Abbad al-Rundi, and more generally the Shadhili tariqa (Shadhili school), were influential on St. John, and draws detailed connections between their teachings. Other scholars, such as José Nieto, argue that this mystical doctrine is quite general, and that while similarities exist between the works of St. John and Ibn Abbad and other Shadhilis, these reflect independent development, not influence. [11] In popular culture F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote the famous line "In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o'clock in the morning" in The Crack-Up. Author and humorist Douglas Adams satirized the phrase in the title of his 1988 science fiction novel, The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul. It has also been used as a song title by several bands and music artists, including Steve Bell, Loreena McKennitt, The Get Up Kids, Mayhem and by CHH artist shai linne in the Solus Christus project. Norwegian band Mayhem named a song of their 2004 album Chimera (Mayhem album) Dark Night of The Soul. Bill Murray's character in the movie Groundhog Day makes a reference to Dark Night of the Soul. In the final episode of Father Ted ("Going to America"), depressed priest Father Kevin explains to Ted that he is experiencing the "dark night of the soul". In episode 5371 of US soap series The Bold and the Beautiful, Bridget Forrester (Ashley Jones) and Brooke Logan (Katherine Kelly Lang) discuss spirituality and the purpose of human existence through reference and direct quotation of "Dark Night of the Soul". An album by Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse, and featuring a 100+ page photo book by David Lynch entitled "Dark Night of the Soul" was set to be released in the summer of 2009[12]. The book can currently be purchased along with a blank CD-R[13]. Santiago de Compostela (also Saint James of Compostela) is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Located in the north west of Spain in the Province of A Coruña, it was a "European City of Culture" for the year 1998. The city's Cathedral is the destination today, as it has been throughout history, of the important 9th century medieval pilgrimage route, the Way of St. James (Galician: Camiño de Santiago, Spanish: Camino de Santiago). The Archdiocese of Santiago de Compostela hosted one of the Catholic World Youth Day gatherings. Folk etymology for the name "Compostela" is that it comes from the Latin "Campus Stellae" (i.e. Stars Field), but it is unlikely such a phonetic evolution takes account of normal evolution from Latin to Galician-Portuguese. A more probable etymology relates the word with Latin "compositum", and local Vulgar Latin "Composita Tella", meaning "burial ground" as a euphemism. Many other places through Galicia share this toponym (with identical sense) and there even exists a "Compostilla" in the León province. William Butler Yeats (pronounced /ˈ jeɪts/; 13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, and one of the foremost figures of 20th century literature. The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare, estimated to have been written in 1610–11, although some researchers have argued for an earlier dating. The play's protagonist is the banished sorcerer Prospero, rightful Duke of Milan, who initially uses his magical powers to punish his enemies when he raises a tempest that drives them ashore. The entire play takes place on an island under his control whose native inhabitants, Ariel and Caliban, respectively aid or hinder his work. While listed as a comedy when it was initially published in the First Folio of 1623, many modern editors have since re-labeled the play as one of Shakespeare's late romances. Synopsis Prospero and Miranda from a painting by William Maw Egley; ca. 1850. The magician Prospero, rightful Duke of Milan, and his daughter, Miranda, have been stranded for twelve years on an island after Prospero's jealous brother Antonio—helped by Alonso, the King of Naples—deposed him and set him adrift with the then three-year-old Miranda. Gonzalo, the King's counsellor, had secretly supplied their boat with plenty of food, water, clothes and the most-prized books from Prospero's library. Possessing magic powers due to his great learning, Prospero is reluctantly served by a spirit, Ariel, whom Prospero had rescued from a tree in which he had been trapped by the Algerian witch Sycorax. Prospero maintains Ariel's loyalty by repeatedly promising to release the "airy spirit" from servitude. Sycorax had been banished to this island, and had died before Prospero's arrival. Her son, Caliban, a deformed monster and the only non-spiritual inhabitant before the arrival of Prospero, was initially adopted and raised by him. He taught Prospero how to survive on the island, while Prospero and Miranda taught Caliban religion and their own language. Following Caliban's attempted rape of Miranda, he had been compelled by Prospero to serve as the sorcerer's slave, carrying wood and gathering berries and "pig nuts" (acorns). In slavery, Caliban has come to view Prospero as a usurper and has grown to resent him and his daughter. Prospero and Miranda in turn view Caliban with contempt and disgust. The play opens as Prospero, having divined that his brother, Antonio, is on a ship passing close by the island, has raised a tempest which causes the ship to run aground. Also on the ship are Antonio's friend and fellow conspirator, King Alonso of Naples, Alonso's brother and son (Sebastian and Ferdinand), and Alonso's advisor, Gonzalo. All these passengers are returning from the wedding of Alonso's daughter Claribel with the King of Tunis. Prospero, by his spells, contrives to separate the survivors of the wreck into several groups. Alonso and Ferdinand are separated and believe one another to be dead. Miranda by John William Waterhouse. Three plots then alternate through the play. In one, Caliban falls in with Stephano and Trinculo, two drunkards, whom he believes to have come from the moon. They attempt to raise a rebellion against Prospero, which ultimately fails. In another, Prospero works to establish a romantic relationship between Ferdinand and Miranda; the two fall immediately in love, but Prospero worries that "too light winning [may] make the prize light", and compels Ferdinand to become his servant, pretending that he regards him as a spy. In the third subplot, Antonio and Sebastian conspire to kill Alonso and Gonzalo so that Sebastian can become King. They are thwarted by Ariel, at Prospero's command. Ariel appears to the "three men of sin" (Alonso, Antonio and Sebastian) as a harpy, reprimanding them for their betrayal of Prospero. Prospero manipulates the course of his enemies' path through the island, drawing them closer and closer to him. In the conclusion, all the main characters are brought together before Prospero, who forgives Alonso. He also forgives Antonio and Sebastian, but warns them against further betrayal. Ariel is charged to prepare the proper sailing weather to guide Alonso and his entourage (including Prospero himself and Miranda) back to the Royal fleet and then to Naples, where Ferdinand and Miranda will be married. After discharging this task, Ariel will finally be free. Prospero pardons Caliban, who is sent to prepare Prospero’s cell, to which Alonso and his party are invited for a final night before their departure. Prospero indicates that he intends to entertain them with the story of his life on the island. Prospero has resolved to break and bury his staff, and "drown" his book of magic, and in his epilogue, shorn of his magic powers, he invites the audience to set him free from the island with their applause. Sources Sylvester Jordain's "A Discovery of the Barmudas". There is no obvious single source for the plot of The Tempest; it seems to have been created out of an amalgamation of sources. Since source scholarship began in the 18th century, researchers have suggested that passages from Erasmus's Naufragium (The Shipwreck, published in 1523 and translated into English in 1606) and Richard Eden's 1555 translation of Peter Martyr's De orbo novo (or Decades of the New Worlde Or West India, 1530) influenced the composition of the play. In addition, many scholars see parallel imagery in a work by William Strachey, an eyewitness report of the real-life shipwreck of the Sea Venture in 1609 on the islands of Bermuda while sailing toward Virginia; a character in the play makes reference to the "still-vexed Bermoothes." Strachey's report was written in 1610; although it was not printed until 1625, it circulated in manuscript and many critics think that Shakespeare may have taken the idea of the shipwreck and some images from it. Another Sea Venture survivor, Sylvester Jordain, also published an account, A Discovery of The Barmudas, so the event would have been widely known. Kenneth Muir warns that even though "[t]here is little doubt that Shakespeare had read ... William Strachey's True Reportory of the Wracke" and other accounts, "[t]he extent of the verbal echoes of [the Bermuda] pamphlets has, I think, been exaggerated. There is hardly a shipwreck in history or fiction which does not mention splitting, in which the ship is not lightened of its cargo, in which the passengers do not give themselves up for lost, in which north winds are not sharp, and in which no one gets to shore by clinging to wreckage," and goes on to say that "Strachey's account of the shipwreck is blended with memories of St Paul's – in which too not a hair perished – and with Erasmus' colloquy." Along these lines, as a possible source for the play, modern researchers have recently added Ariosto's 1516 Orlando Furioso, which contains many of the storm references also found in Naufragium.[ The Tempest may take its overall structure from traditional Italian commedia dell'arte, which sometimes featured a magus and his daughter, their supernatural attendants, and a number of rustics. The commedia often featured a clown known as Arlecchino (or his predecessor, Zanni) and his partner Brighella, who bear a striking resemblance to Stephano and Trinculo; a lecherous Neapolitan hunchback named Pulcinella, who corresponds to Caliban; and the clever and beautiful Isabella, whose wealthy and manipulative father, Pantalone, constantly seeks a suitor for her, thus mirroring the relationship between Miranda and Prospero. [9] One of Gonzalo's speeches is derived from Montaigne's essay Of the Canibales, which John Florio translated into English in 1603, that praises the society of the Caribbean natives: It is a nation . . . that hath no kinde of traffike, no knowledge of Letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politike superioritie; no use of service, of riches, or of poverty; no contracts, no successions, no dividences, no occupation but idle; no respect of kinred, but common, no apparrell but naturall, no manuring of lands, no use of wine, corne, or mettle. The very words that import lying, falsehood, treason, dissimulation, covetousnes, envie, detraction, and pardon, were never heard of amongst them. In addition, much of Prospero's renunciative speech is taken word for word from a speech by Medea in Ovid's poem Metamorphoses.