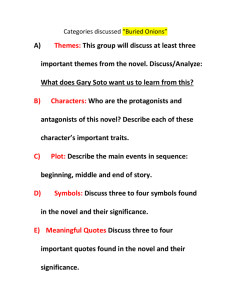

SUSAN GEASON

advertisement