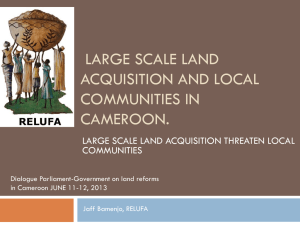

Cameroon

advertisement