Reflections

advertisement

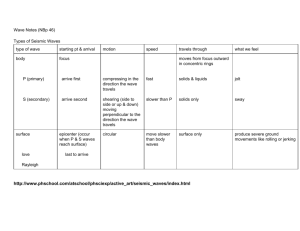

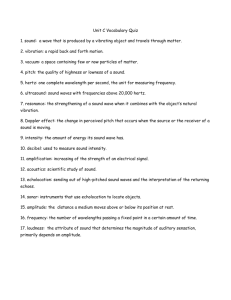

UNIT 8: OSCILLATIONS, WAVES AND SOUND Relationship to Labs: This unit is supported by Lab 7: The Simple Pendulum (kit-based lab). It may also be supported by Lab 8: Cathode Ray Oscilloscope and the Speed of Sound (RWSL). HOOKE’S LAW When you push on a spring, it pushes back. When you stretch a spring, it pulls back towards its unstretched position. When the spring is un-stretched or un-compressed, it is in what is called the equilibrium position. F=0 F F equilibrium position If we will define x = 0 at the equilibrium position, Hooke’s Law states that the force due to the spring is Fx kx where k is the spring constant. This is the restoring force because it is the force that restores the string to its equilibrium position. The negative sign indicates that the restoring force is always opposite the displacement from equilibrium. Also note that the restoring force gets larger as the object gets further from the equilibrium position. We can use Newton’s 2nd Law to find the acceleration of a mass m attached to the end of the spring (spring usually has no mass for introductory physics course). max kx ax k x m Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 1 or ax cx Using calculus, this becomes d 2x k x 2 dt m or d 2x cx dt 2 where c is a constant. Here the second derivative of the displacement with respect to time (the acceleration) is proportional to the displacement and the second derivative is in the direction opposite that of the displacement. Systems with the relations between the restoring force and the displacement will undergo simple harmonic motion (SHM) when displaced from equilibrium. A mass attached to a spring that is displaced and released will oscillate back and forth until friction forces dissipate this motion. SHM shows up all over the place. This is very convenient because, once we know how to deal with one system under SHM, we can apply the basic principles to any system undergoing SHM (variable names may change but the form is the same). This is so useful that, whenever you see an equation of the form d 2x cx , dt 2 a cx or Fx kx , you can think “this is SHM”, and apply your SMH relations to the new case. Consider the function x sin c t c t c t cx v dx c cos dt a dv c sin dt first derivative second derivative We can get the same result with x cos c t . It turns out that any object undergoing SHM can have its displacement described by a sine function, cosine function or combination of the two as a function of the time. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 2 In general, the displacement is defined using the wave equation x A cost where ω is the angular speed or angular frequency, A is the amplitude and is the phase (also phase angle or phase constant). We will use cosine because mass-spring systems and pendulums usually start at the maximum displacement from equilibrium and cos t is at a maximum when t 0 . In reality, we can start timing (t = 0) whenever we want so we allow for variation in start time with the phase angle. The wave equation is a sine function if we let the phase equal –π/2. This is a consequence of the trigonometric relationship cos t sin t 2 Because the sine and cosine function have values between –1 and +1, this function will have values between –A and +A. The amplitude describes the range of x values, the size of the oscillation. This is the position-time curve for an object oscillating back and forth along the x-axis. Sample wave equations with different amplitudes and phase angles are shown. 4 x x 3 cos t 3 x cost 0.5 2 x cos t 1 t 0 -1 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 -2 -3 -4 The basic curve is shown in blue. If we increase the amplitude, we get the red line. If we change the phase the curve shifts to the left or right in time. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 3 The angular frequency is a measure of how rapidly the oscillations occur. The units of angular frequency are s-1 or radians per second. The plot below shows samples. x 1.5 x cost / 2 x cos2t x cos t 1 0.5 t 0 -1 -0.5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 -1 -1.5 Once again, the basic curve is in blue. The dotted cyan curve is for the oscillation with twice the frequency as the basic curve. The dashed purple curve is for an oscillation with half the frequency. All curves have the same magnitude and phase. The first derivative of x A cost is dx A sin t dt The second derivative is d 2x A 2 cost 2 dt The substituting the original equation on the left, second derivative is d 2x 2 x dt 2 or a 2 x This has the same form as the SHM equation we had for the spring motion d 2x k x 2 dt m Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 4 The two equations are identical if we let 2 k m or k m Notice that the angular frequency is not proportional to the amplitude. It doesn’t matter how much the spring is stretched, the angular frequency of the oscillation is constant. The period of an oscillation is the time that it takes to complete one full oscillation. Periods for the basic curve and the one with twice the frequency are shown in the position-time curve below. x 1.5 T1 1 0.5 t 0 -1 -0.5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 -1 T2 -1.5 The period is related to the angular frequency by T 2 2 m k Period is measured in seconds. Continuing with the definitions, we can also define the frequency f is the number of oscillations the object undergoes per unit time interval. It is also the inverse of the period. f 1 1 T 2 k m The units of frequency are cycles per second, or Hertz (Hz). Like radians, cycles have are unit-free. In cases where the motion is due to rotation, we can define frequency in revolutions per second or revolutions per minute (RPM). The angular frequency is a measure of the angle (in radians) the oscillating object goes through in 1 s. One cycle for a sine or cosine curve is equivalent to 2 radians. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 5 The frequency f is then related to the angular frequency by f 2 or k m Problem 1 Find the angular frequency, frequency and period of the simple harmonic motion of a 1.0 kg mass attached to an ideal spring with spring constant 6.4 N/m if the amplitude of motion is 2.5 cm. Let’s look at displacement and its derivatives a little closer. We had the displacement as x A cost The position-time graph shows the simple case x cos 2t , A 1 , 2 and 0 . -1 5 x 4 3 2 1 0 -1 0 -2 -3 -4 -5 x cos( 2t ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 t As noted earlier, the maximum and minimum values of the displacement are ±A, ±1 in this case. In the kinematics section, we saw that the instantaneous velocity at any time is the slope of the curve at that time. We can use calculus to show that vx dx dt A sin t or vx A sin t Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 6 Notice that the amplitude of the velocity curve is A . The velocity-time curve for the simple case is shown below. The maximum and minimum values of the velocity are ±ωA, ±2 in this case. Also note that the curve is shifted to the left by / 2 / 4 . 5 4 3 vx 2 sin( 2t ) 2 1 0 -1 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 -2 -3 -4 -5 Kinematics also showed us that the instantaneous acceleration is the slope of the velocity-time curve. We can verify this using calculus 2 ax d x dt 2 A 2 sin t or ax A 2 cos t The amplitude of the acceleration-time curve is A 2 . The acceleration-time curve for the simple case is shown below. The maximum and minimum values of the acceleration are ±ωA2, ±4 in this case. Also note that the curve is shifted to the left by another / 2 / 4 . -1 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 0 -2 -3 -4 -5 ax 4 cos( 2t ) 1 2 3 4 5 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 6 7 8 9 10 7 Plotting displacement, velocity and acceleration together, we see that the maximum or minimum displacement occurs when the velocity crosses zero. The max/min displacement occurs at the same time as the min/max acceleration. We can also see that the maximum or minimum velocity occurs when the acceleration and displacement are zero. -1 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 0 -2 -3 -4 -5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 max/min velocity occurs when both acceleration and displacement are max/min displacement and min/max acceleration occur when velocity is zero zero 10 Problem 2 A 3.0 kg block is connected to a spring with an elastic constant of 12 N/m. If the block is initially displaced 2.0 m from the equilibrium position and released from rest: a) calculate the amplitude, period and angular frequency; b) calculate the displacement, velocity and acceleration when t = 0.76 s. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 8 ENERGY OF A SIMPLE HARMONIC OSCILLATOR The elastic potential energy of stored in the spring of a system undergoing SHM of the form x A cost is U 12 kx 2 12 kA2 cos2 t The kinetic energy of the same system is K 12 mv 2 12 m 2 A2 sin 2 t We will use the fact that 2 k m m 2 k or to combine the equations to find the total energy E K U 12 m 2 A2 sin 2 t 12 kA2 cos 2 t 12 kA2 sin 2 t 12 kA2 cos 2 t 12 kA2 sin 2 t cos 2 t 12 kA2 constant Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 9 The kinetic, potential and total energies are plotted as functions of time in the figure below. 2.5 E 2 1.5 K U 1 0.5 0 -1 -0.5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The mass oscillates back and forth. The energy is converted between elastic potential energy and kinetic energy (horizontal system). The total energy remains constant. When we first looked at spring energy in the Energy section, we had K U 12 mv 2 12 kx 2 constant 12 kA2 We can use the energy relationship to find either the position or velocity when we know the total energy and velocity or position. Problem 3 A 79 kg student is connected to a spring with a spring constant of 250 N/m. The student is on a frictionless horizontal surface. a) Calculate the total energy of the system if the maximum displacement is 3.0 m. b) What is the velocity of the student when the position is 1.0 m. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 10 SMALL ANGLE APPROXIMATION The small angle approximation is a useful way to estimate sin , cos and tan when then angle is less than 0.1 or 0.2 radians. The angle must be in radians, for the approximation. The approximations are: sin , cos 1 , and tan Let’s try a few values for angles up to 0.25 radians. The percent differences are %difference appoximation trigonometry function 100% trigonometry function (radians) sin % diff cos % diff tan % diff 0.00000 0.00000 0.00 1.00000 0.00 0.00000 0.00 0.05000 0.04998 0.04 0.99875 0.13 0.05004 -0.08 0.10000 0.09983 0.17 0.99500 0.50 0.10033 -0.33 0.15000 1.14494 0.38 0.98877 1.14 0.15114 -0.75 0.20000 0.19867 0.67 0.98007 2.03 0.20271 -1.34 0.25000 0.24740 1.05 0.96891 3.21 0.25534 -2.09 All approximations have small percent differences for these angles, with sin best. The approximations can be viewed geometrically. hypotenuse r arc length r side opposite , length r sin side adjacent to , length r cos With small values of , the right triangle is almost an isosceles triangle with the length side adjacent to nearly equal to the length of the hypotenuse. r cos r or cos 1 We can also see that the length side opposite nearly equal to the arc length. r sin r or sin The tangent approximation follows from the sine and cosine approximations, tan Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License sin . cos 1 11 PENDULUM Consider the case where a ball, mass m, on the end of a string, length L, swinging back and forth. y x T L θ mg mgcosθ mgsinθ s The object is constrained to move at a constant radius L about the pivot so we can define our dimensions with the y-direction along the radius. The radius is constant so there is no movement in the y-direction parallel to the tension. This gives T mg cos The net force is only that in the x-direction. Fnet mg sin This causes acceleration along the arc traced by the pendulum m d 2s dt 2 d 2s dt 2 mg sin or g sin ma mg sin a g sin We can now use the small angle approximation sin This works when is in radians and the angle is small. The motion of the pendulum for small angles is then d 2s g dt 2 or Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License a g 12 Further, we can use the definition of arc length s L or, with a bit of work d 2s dt 2 L d 2 dt 2 or a L This gives us our final form of motion for the pendulum L d 2 dt 2 d 2 dt 2 g L g or g L g L This is simple harmonic motion with the angular frequency and period g L and T 2 L g We can repeat the same set of arguments for a body with mass m, moment of inertia I and distance from pivot to centre of mass d. Here d 2 mgd 2 dt I and mgd I Problem 4 Find the angular frequency and period of a swinging log with mass 1200 kg, length 4.2 m (need to divide the length by 2 to get the distance to the centre of mass) and moment of inertia 7040 kg·m2. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 13 CIRCULAR MOTION Consider the uniform circular motion of an object on a merry-go-round with the centre of rotation as the origin. The speed of the object is constant v. The angular speed (angular frequency) of the object is v A y If the measurement started when the angle between the line A θ x joining the object to the origin and the x-axis was 0 , the angle at time t is t t The x-position of the object at time t is x A cos A cost This is the same equation we had for linear motion in a simple harmonic oscillator. The y-position of the object at time t is y A sin t A cos t 2 This is another equation that works with the linear simple harmonic motion. Uniform circular motion can be considered a combination of two simple harmonic motions, one each in the x- and y- directions, with the two differing in phase by 2 or 90°. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 14 OPTIONAL/REVIEW TOPICS VIBRATIONS AND WAVES Vibrations and waves are everywhere. The ground vibrates when a train passes. The crystals inside electronic watches vibrate at specific frequencies so precise the watches rarely require adjusting. Waves appear in on the surface of water. Sound waves travel through the air. Light behaves as a wave under certain conditions. Even matter can be thought of as vibrations or waves in a multidimensional string. Some definitions: oscillation repetitive motion or variation of some value in time the value that oscillates could be anything from air pressure to fashion trends to fish populations oscillations usually occur about some equilibrium position vibration specific form of mechanical oscillation about an equilibrium position we will look at spring and pendulum vibrations wave oscillation that travels in space oscillation or vibration that moves away from the initial disturbance period, T the time for an oscillation to repeat itself frequency, f the number of times and oscillation repeats itself in a second reciprocal of the period, f 1 T In this section, we will look at the oscillations in springs, pendulums and objects in circular motion. This section is a nice recap of earlier dynamics and kinematics relations. We will also look at several properties of waves, specifically sound waves. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 15 WAVES A mechanical wave involves some form of disturbance that propagates though a material. The material through with the waves propagate is known as a medium. A medium possesses some physical property that allows adjacent elements within the medium to affect each other. Here are some examples mechanical wave medium physical mechanism sound air pressure surface waves water pressure pulse in rope rope tension A travelling wave or pulse that causes the elements of the disturbed medium to move perpendicular to the direction of propagation is called a transverse wave. A travelling wave or pulse that causes the elements of the disturbed medium to move parallel to the direction of propagation is called a longitudinal wave. When a wave travels around an arena, the participants stand and wave as the wave passes but then sit back down to enjoy the show. You can also line up people shoulder-to-shoulder and lightly push a person at one end towards the others. The wave will travel through the line (It helps to have a safety person at the other end to catch the last person in the line.) In both cases, the waves pass through the group with minimal disturbance to the individuals in the wave. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 16 Physical waves behave in the same way. Waves propagate through a medium with minimal disturbances to the medium itself. A wave will pass through you when you are swimming. You will go up and down as the wave passes but you will not move along with the wave. The speed of the waves or wave speed is a measure of how quickly the disturbance propagates through the medium. Consider the following transverse wave. At time, t = 0, the disturbance is vt v y y v x t=0 x t=t For a disturbance travelling to the right at point x at time t is the same disturbance that was at x – vt at time t = 0. We can write this mathematically as yx, t f x vt where the wave function y(x, t) represents the y-coordinate of the element along the wave at position x at time t. If the wave is travelling to the left, we can use the same argument to get. yx, t f x vt Example A pulse moving to the right along the x axis has the wave function y x, t 10 x 2t 2 1 where x and y are in meters and t is in seconds. a) Find the speed of the wave. The varying portion of the equation is x 2t . Comparing this to the form of the wave travelling to the right, gives x vt x 2t Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 17 This is true for all x and t so we can make the two sides equal by setting v 2 m/s The speed is 2 m/s to the right b) Find the disturbance of the wave at the following times and locations. y x=0m x=2m x=4m x=6m x=5m t=0s 10 2 0.6 0.3 0.2 t=1s t=2s t=3s t=4s You can verify that the wave moves in the positive x-direction. The waves are plotted at the following link wave propagation spreadsheet. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 18 SINUSOIDAL WAVES Sine waves are the simplest example of a periodic continuous wave. In fact there are theories (Fourier), analyses and functioning devices that exploit the fact that all waves and, to some extent, pulses can be represented by sums of sine waves. These waves are very similar to the simple harmonic motion vibrations. Where SHM has displacement (position) x varying as a function of time t, sine waves vary have the dependent displacement variable y as a function of both position x and time t. We will also use the frequency f for sine waves instead of the angular frequency . Here are graphs of a sine wave versus both x and t. The first is a plot of the displacement in the ydirection as a function of position x at one instant in time. -1 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 0 -2 -3 -4 -5 y λ A x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The wavelength λ is the distance between any two identical points on adjacent waves. The amplitude A is the height of the wave. -1 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 0 -2 -3 -4 -5 y T A t 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 This is the graph at a single point x in space. The displacement in the y-direction varies with time. The period T is the time between any two identical points on adjacent waves. The amplitude A is the height Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 19 of the wave (it is the same as when y is plotted versus x because it is a measure of the maximum yvalue). Just like earlier in this section, the frequency f is the inverse of the period. f 1 T Frequency is usually given in hertz (Hz) or cycles per second (s-1). The equation for the sine wave is 2 x vt y x, t A sin The wave travels a distance of one wavelength in one period, so we can define the wave speed as v T f The sine wave equation is then 2 y x, t A sin x t T x t A sin 2 T We can use our good old angular frequency (or angular speed) ω and introduce the wave number k 2 T and k 2 to get y x, t A sin kx t Finally, we can install a phase constant to get y x, t Asin kx t The phase constant can be found using the initial conditions (the description of the wave at t = 0, x = 0). When t = 0 and x = 0, the wave equation simplifies to Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 20 y 0,0 A sin y 0,0 A arcsin To continue loading on the formulas, we can also express the wave speed using the new terms. v k Problem 5 Estimate the wavelength, amplitude, period, frequency, angular frequency, wave speed, wave number and phase constant of the following sine wave. Use proper units. 4 y (cm) 3 2 1 t (s) 0 -1 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 -2 -3 -4 4 y (cm) 3 2 1 x (m) 0 -2 -1 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 -2 -3 -4 A λ v T f ω k Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 21 Problem 6 A sine wave travelling to the right with an amplitude of 8.0 cm, a wavelength of 60.0 cm, and a frequency of 10.0 Hz. a) Find the period, and speed of the wave. b) If the initial conditions state that, at x = 0 and t = 0, the vertical position is y = -6.0 cm, determine the phase constant (phase angle) and write a general expression for the wave function. WAVES IN A STRING The speed of a wave in a string is v T where T is the tension of the string and μ is the mass per unit length of the string. Problems 7 a) A uniform cord has a mass of 0.100 kg and a length of 10.0 m. The cord passes over a pulley and supports a 16.0 N object. Find the speed of a pulse travelling along the cord. b) A Bob and Anne are talking on a string phone. The string is 15 m long and has a mass of 0.20 kg. What is the tension on the line if it takes 0.50 s for a message to travel from Anne to Bob? Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 22 Reflection and Transmission When a wave encounters a change in medium, in most cases a portion of the wave will be reflected back in the direction it came and another portion of the wave will be transmitted into the new medium. When an incident wave is comes to a fixed point, the wave exerts a force on the fixed point and, according to Newton’s 3rd Law, the fixed point exerts the opposite force on the wave. This creates a reflection of the original wave that is inverted with respect to the original but otherwise unchanged (except the direction change). When an incident wave is comes to a free end, the reflected wave is not inverted with respect to the original and otherwise unchanged (except the direction change). Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 23 Similar things happen when the medium changes from one type of string to another. In both cases, there is a transmitted wave that travels into the second string. The transmitted wave always has the same orientation to the original wave. If the wave travels from a light string to a heavy string, this is like the case with the fixed end because the mass of the heavy string will resist moving. The reflected wave is inverted. light string heavy string If the wave travels from a heavy string to a light string, this is like the case with the free end because the mass of the light string will provide little resistance to the movement of the heavy string. The reflected wave is not inverted. heavy string light string I like to think of this in terms of elastic collisions. When a light object collides with a stationary heavy object, the light object will reverse directions (think of the wave movement in the y-direction). When a heavy object collides with a stationary light object, the heavy object will maintain its original direction (think of the wave movement in the y-direction). In either case, the originally stationary object will end up moving in the same direction as the original moving object. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 24 SOUND Sound waves are longitudinal waves that travel through a medium. If you hit a tuning fork, the tines will oscillate back and forth. This movement creates a series of high and low pressure regions in the air (compression and rarefaction) that travel outwards from the tuning fork (longitudinal waves). position of high pressure region travelling away from slope is the speed of sound tuning fork position low pressure high pressure time All sound waves behave in this manner. Audible sound waves are in the range of frequencies between 20 and 20 000 Hz. Infrasonic waves have frequencies below the audible range (earthquake waves). Ultrasonic waves have frequencies above the audible range (ultrasound, dog whistles). Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 25 With string we had the wave speed v T This expression has the square root of an elastic term, tension, divided by a density term, mass per unit length. The speed of sound in a gas has a similar expression v B This expression has the square root of an elastic term, bulk modulus, divided by a density term, mass per unit volume. Both terms in the expression for sound waves depend on temperature. For air, the result is v 331 m/s 1 TC 273C where TC is the temperature in degrees Celsius. The -273°C is absolute zero. The table below shows the speeds of sound for longitudinal waves in various bulk media. Medium v (m/s) Medium Gases v (m/s) Medium Liquid v (m/s) Solid helium (0°C) 970 seawater 1 530 steel 6 000 air (0°C) 331 fresh water 1 480 glass 4 000 air (20°C) 343 chloroform 1 000 lead 2 000 Note: The values shown here are approximate, and are intended for demonstration purposes only. Check the textbook, on-line, and in reference books to find more accurate values for a wider array of materials. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 26 Problems 8 a) Lightning strikes a tree 3.0 km away. You see the light 10 μs later. If the air temperature is 12°C, how long is it before you hear the sound? b) Calculate the bulk modulus of water based on the speed of sound. As the tuning fork oscillates the pressure waves move outward from it. The pressure varies between the high and low pressure regions. The air oscillates between compression and rarefaction. λ slice view P of speaker x We can write the pressure change from normal air pressure as P Pmax sin kx t The pressure wave causes the air particles to move back and forth. The displacement molecules is given by s smax coskx t The pressure is 90° out of phase with the displacement. I recommend you check out the derivations of these expressions in the text. ΔP s Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 27 SOUND INTENSITY As the wave moves along it carries energy with it. This energy is converted into electrical signals when it enters a microphone, and into nerve signals when enters our ears. With a bit of work, we can show that the energy in one wavelength is E 12 A smax 2 where A is the area perpendicular to the direction of wave motion and ρ is the density of the medium. We can divide this by the period to get the rate of energy transfer (power) in one period of oscillation. P 1 2 A smax 2 used v T 12 A smax v 2 T The intensity of the wave is the power per unit area. We can find the intensity by dividing by the power by the area. I P A 1 2 A smax v 2 A 12 v smax 2 We can link in the pressure to get I 2 Pmax 2 v Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 28 Unless impeded or guided, most sound waves will travel in spherical waves. They travel with equal intensity in all directions until hitting something. Think of a fire cracker dropped into the air and exploding. The sound expands from the firecracker in all directions at the same speed so we get a spherical wave front for the sound. wave fronts (crests) moving outward λ For a spherical wave, we can do some averaging to get Pave P ave2 A 4 r I Notice that the intensity at some distance r1 from the source is I1 Pave 4 r12 If we look at a different distance r2 from the source, we get I2 Pave 4 r22 The ratio of the intensities at the two points is Pave I2 4 r12 I1 Pave 4 r12 r12 r22 The ratio of intensities is the inverse of the ratio of the squares of the radii. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 29 Problem 9 A source emits waves with a power output of 120 W. a) Find the intensity 12 m from the source. b) Find the distance at which the intensity is 10.0% of that in part a). Decibels (dB) The loudest sounds the ear can tolerate have an intensity of 1 W/m2. For 1000 Hz sound, the quietest sounds the ear can detect have intensity as low as 10-12 W/m2. This is a huge range of intensities from 10-12 W/m2 to 1 W/m2. A much more convenient term is the decibel. The decibel is a comparison to the minimum level. Intensity described in decibels using I I0 10 log 10 where I0 = 10-12 W/m2. Examples A sound with intensity of 10-12 W/m2 has a decibel level of 1012 W/m 2 10 log 10 1 0 dB 12 2 10 W/m 10 log 10 A sound with intensity of 10-11 W/m2 has a decibel level of 1011 W/m 2 10 log 10 10 10 dB 12 2 10 W/m 10 log 10 A sound with intensity of 5.0×10-5 W/m2 has a decibel level of 5.0 105 W/m 2 10 log 10 5.0 107 77 dB 12 2 10 W/m 10 log 10 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 30 When working with decibels we use the properties of the logarithm log10 AB log10 A log10 B A log10 log10 A log10 B B Example Bob’s neighbours were at it again, playing their soft rock too loud. Inside Bob’s house, the sound level for the neighbours’ music was 72 dB. If the neighbours increased their volume by a factor of 5, what sound level would Bob hear in his house? terms: I I1 1 10 log10 1 72 dB, I 2 5I1 , I0 2 ?, I 0 1012 W/m2 new dB level: I2 I0 2 10 log10 5I 10 log10 1 I0 I 10 log10 5 10 log10 1 I0 7.0 1 79 dB Bob would hear the soft rock at 79 dB. problem 10 The intensity of sound produced by a mosquito 5.2 cm from your ear is 42 dB. a) Find the decibel level, if there are two similar mosquitoes 5.2 cm from your ear. b) Find the decibel level after you swat one mosquito and the remaining one moves 52 cm from your ear. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 31 DOPPLER EFFECT If you sit on the side of a road or railroad track and listen to the sound of their horn, you will probably hear a change in frequency (tone) as the vehicle moves past. This is known as the Doppler effect. To picture this, think of a moving object that is emitting sound. The high pressure regions (wave crests) are shown in the figures. A wave front forms a circle centred on the point where the wave was created. The object moves so the circles for successive circular wave fronts also move forming the patterns below. The motion is relative, it makes no difference whether you or the source do the actual moving. wavelength, λ Stationary Source observer source wave crests Source Moving Toward Observer source wavelength, λ′ < λ observer wave crests Source Moving Away from Observer wavelength, λ′ > λ source observer wave crests Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 32 As seen in the figures, the wavelength changes (or appears to change in the view of the observer). The wavelengths shrink/grow by the distance the source moves each period vS T where vS is the speed of the source towards to the stationary observer. The observed wavelength is vS T vS f The wave is still coming at the observer at the speed of sound v so the observed frequency is f v v vS f v v f vS f v f v vS moving source If the source moves towards the observer, the observed frequency increases. Example If the speed of sound is 330 m/s, the observed frequency of a 200 Hz signal emitted by a source moving at 30 m/s towards the observer is v 330 f f 200 Hz 220 Hz 330 30 v vS If the source is moving away from the observer, vS 30 m/s and the observed frequency is v 330 f 200 Hz 183 Hz f v v 330 30 S Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 33 In the case where the observer moves towards the stationary source, the wavelength is unchanged but the speed becomes v v vO where vO is the speed of the observer. The modified frequency is then f v v vO v vO f v v vO f v moving observer If the observer moves towards the source, the observed frequency increases. If the observer moves away from the source, the observe frequency decreases. To someone who is stationary, there is not change in frequency. Example If the speed of sound is 330 m/s, the observed frequency by an observer moving at 30 m/s towards a stationary source making a 200 Hz signal is v vO f v 330 30 f 330 200 Hz 218 Hz If the observer is moving away from a stationary source at vO 30 m/s and the observed frequency is 330 30 v vO f f 200 Hz 182 Hz 330 v The general expression for the Doppler frequency shift is v vO f f v vS If the observer and source are moving towards each other, the observed frequency increases. If the observer and source are moving apart, the observed frequency decreases. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 34 Shock Waves If the source is travelling faster than the speed of sound, the spherical waves still start at the source, but no waves travel in front of the source because it outruns the sound. The wave crests of sound emitted at different times build up to form a shock front. We can see shock waves that build up on the surface of water behind a boat that travels faster than the surface wave speed. shock front source Reflections One of the first things that people do when they enter a very large, empty, enclosed or partially encloses space is yell “Hello” (or a similar term in other languages), and then listen for the echo. When a sound wave strikes a rigid structure like a large wall or a cliff, it changes direction and continues to on in the opposite direction (assuming the sound was initially travelling perpendicular to the wall). Problem 11 As Bob drove towards a large cliff, he blasted his horn and listened for the echo. If the horn emits an annoying 620 Hz tone, what is the frequency of the echo? Assume that the speed of sound in air is 330 m/s. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 35 INTERFERENCE OF WAVES The superposition principle states: If two or more travelling waves are moving through a medium, the resultant value of the wave function at any point is the algebraic sum of the values in the wave functions of the individual waves. In this figure we have two waves, one moving to the left and one moving to the right. When the two waves meet, there displacements add due to superposition. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 36 In the following figure, we have two transverse waves with displacements in the opposite direction travelling towards each other. As per the superposition principle, we still add the displacements, but due to the opposite displacements, the waves tend to cancel each other out when they meet. Both cases show the consequence of superposition principal and that two travelling waves can pass through each other without being destroyed or even altered. Check out http://phet.colorado.edu/new/simulations/sims.php?sim=Wave_on_a_String. Set the tension (mid-way or less) to slow the pulse. Try sending pulse in the same direction and in opposite directions. More on this applet later… The combination of separate waves in the same region is called interference. When two waves with displacements in the same direction interfere, the superposition is larger than either single wave. This is constructive interference. When two waves with displacements in opposite direction interfere, the superposition is reduces the displacement. This is destructive interference. Consider the interference of the two waves y1 A sin kx t and Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License y2 A sin kx t 37 Both waves are travelling in the same direction with speed v k The superposition of the two waves results in the wave function y y1 y2 A sin kx t A sin kx t Here we can use the relation a b a b sin a sin b 2 cos sin 2 2 with a kx t and b kx t to get a b a b , kx t 2 2 2 2 and y 2 A cos sin kx t 2 2 This figure below shows the typical case where the phase difference is no special value. There is a mix of constructive interference when both waves have the same sign and destructive interference when they have opposite sign. The phase is a constant so the amplitude of the combined signal is Ac 2 A cos 2 with the combined wave y Ac sin kx t . 2 y1 + y2 y1 x y2 The phase is is zero in the following figure. y1 and y2 are identical so y1 + y2 is twice y1 or y2. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 38 y1 + y2 y1 and y2 x We get complete constructive interference whenever the phase term is 0, 2π, 4π … any even multiple of π. If we look at the interference equation, constructive interference occurs when cos 1 2 and Ac 2 A . In this case below, so y1 and y2 are exact opposites. We get complete destructive interference so y1 + y2 is zero. y1 y1 + y2 y2 x Complete destructive interference occurs whenever the phase term is π, 3π, 5π … any odd multiple of π. Looking at the interference equation, we get destructive interference when cos 0 2 and Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License Ac 0 . 39 Problem 12 Find the amplitude due to the superposition of two waves y1 4.0 sin 2.0x 4.0t and y2 4.0 sin 2.0x 4.0t when a) the phase difference is 0.1 , b) the phase difference is 3.0 . Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 40 INTERFERENCE OF SOUND WAVES Imagine two speakers, each playing sound of the same frequency of sound with the same phase. speaker 1 1 speaker 2 2 An observer is a distance r1 from speaker 1 and r2 from speaker 2. r1 and r2 are called the path lengths for the two sources. If the two path lengths are different, the sound will take different amounts of time to reach the observer. sound from speaker 1 sound from speaker 2 observer We can use the wavelengths as the units for the measure of the distance between sources and the r r observer. Speaker 1 is 1 from the observer while speaker 2 is 2 from the observer. The difference in path lengths is r2 r1 r Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 41 The term r is a fraction of a wavelength. Let’s say this term is 0.50, one speaker is half of a wavelength closer to the observer than the other. We can convert this term to the phase difference by multiplying by 2. A value of r 2r 2 0.5 0.50 corresponds to a phase difference of . The value Δr is known as the path length difference. Examples In the diagram below, the phase difference is 2r 2 4.5 4.0 . This is a case where we have complete destructive interference. The sound from one speaker cancels out the sound from the other speaker. The observer hears nothing. r 2 r1 = 4.0 1 2 r2 = 4.5 An application of this is noise-cancelling headphones which determine the frequency and phase of the incoming noise, and then create sound with the appropriate frequency and phase to cancel out the noise from the surroundings. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 42 In the next diagram, the phase difference is 2r 2 4.5 3.5 . 2 This is a case where we have complete constructive interference. The sound is louder than the sound for a single e speaker. r = λ r1 = 3.5 1 2 r2 = 4.5 Below is a more general case. If r1 is 3.7λ away from the observer and r2 is 4.0λ away the observer, the phase angle will be 2r 2 r2 r1 2 4.0 3.7 0.6 1.9 radians 1 2 The interference at the observer is the same situation as earlier. We get constructive interference when Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 43 cos 1 2 0, 2 , 4 … or This is satisfied when 2r 0, 2 , 4 ... or r n where n = 0, 1, 2, … If speakers are playing one frequency, the sound level is higher when the path length difference between you and the speakers is an integer multiple of the wavelengths. We can use similar arguments to show that we get destructive interference when r 2n 1 2 where n = 0, 1, 2, … If speakers are playing one frequency, the sound level is lower or zero when the path length difference between you and the speakers is an integer plus 1 2 multiple of the wavelengths. These properties are difficult to notice in everyday life because we rarely hear a single frequency from a pair of speakers for any significant length of time. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 44 Problem 13 Bob stands in front of two speakers, 12.00 m from each speaker. The speakers produce the same frequency sound with the same phase, so Bob is at a point with constructive interference. Staying 12.00 m from speaker 1, Bob finds the next point of constructive interference when he moves to a point 12.70 m from speaker 2. 1 12.00 m 12.00 m 12.70 m 12.00 m 2 a) What is the wavelength of the sound? b) What is the frequency if the speed of sound is 345 m/s? The applet http://phet.colorado.edu/new/simulations/sims.php?sim=Wave_Interference shows the sound coming from one speaker or from two speakers with interference. With two speakers, set the frequency to something medium low. Notice that there are regions where the waves are grey all of the time and other regions where the waves alternate between black and white. You can place detectors in these regions to show you the pressure oscillation in these areas. The grey regions are the nodal regions where there is destructive interference and the sounds cancel out. The black and white regions are where there is constructive interference so the sound is loud. You can also move the detectors near and far from the speakers and note the change in intensity (pressure). Try varying some of the other parameters or check out the other sound applet. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 45 STANDING WAVES If the two speakers in the previous derivations are facing each other, their waves will be travelling in opposite directions in the space between the speakers. 1 2 Ignoring phase, we can write the wave functions as y1 A sin kx t y2 A sin kx t and Note that the speaker 1 wave function has a speed to the right and the speaker 2 wave function has a speed to the left. This is reflected in the signs in front of the angular frequencies. The combined wave function is y y1 y2 Asin kx t Asin kx t We can use the trig rule a b a b sin a sin b 2 cos sin 2 2 with a kx t and b kx t to get a b ab kc, t 2 2 and y 2 A sin kxcost This is the wave function of a standing wave. It is “standing” because there are points that have zero amplitude; they don’t move in either of the x or y directions. The wave appears to be fixed at these nodes. The amplitudes at the nodes satisfy 2 A sin kx 0 The positions of the nodes occur when kx 0, , 2 , .... n where n 0, 1, 2, ... Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 46 or, using k 2 x 0, , , 3 , ... n 2 2 2 where n = 0, 1, 2 … The cos t term varies between -1 and 1 for all points. The maximum displacement (amplitude) at any position x is ymax x 2 A sin kx The positions that have the largest maximum displacement are those where the sine term is ±1. sin kx 1 The maximum sine values occur when kx 12 , 1 12 , 2 12 , ... Using k 2 , we get x , 3 , 5 , ... n , 4 4 4 4 n = 1, 3, 5 … These points are called antinodes. The distance between adjacent antinodes is . 2 The distance between adjacent nodes is . 2 The distance between a node and an adjacent antinode is . 4 Looking at the wave function again, the whole function is zero if cost 0 . By definition 2 T cost 0 when t nT , 4 n = 1, 3, 5 … t 2, 3 2, 5 2, ... or Similarly, the function has maximum amplitude when cost 1 when t nT , 2 n = 0, 1, 2 … Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 47 This figure shows the positions of nodes a standing wave at different times t=0 t T 4 t T 2 multiple times as the time blurs the image it the wave appears to be stationary antinodes Problem 14 Two waves travel in opposite directions with wave functions y1 0.10 sin 4.0x 3.0t and y2 0.10 sin 4.0x 3.0t where x and y are in meters. a) Find the amplitude of the simple harmonic motion of an element at x = 1.5 m. b) If x = 0 m is a node, find position of the next node and antinode. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 48 Many systems have normal modes which are patterns of oscillation favoured by the natural system. Some are shown below. String with Fixed Ends – Nodes at Ends L L n = 1, λ1 = 2L, f1 = v n = 2, λ2 = L, f2 = v 2L L L fixed ends n = 3, λ3 2 3 L , f13 = 3v fn nv 2 L 1 nf1 , n 2L n n 2L The frequency for n = 1 is the fundamental frequency. Other natural frequencies are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. The frequencies form a harmonic series with higher n frequencies known as harmonics. Positions with no motion are nodes. Positions with lots of motion are loops. Air Column, Both Ends Open – Antinodes at Ends L n = 1, λ1 = 2L, f1 = v open ends L n = 2, λ2 = L, f1 = v 2L fn nv nf1 , 2L n 2 L 1 n n L Air Column, One End Open L n = 1, λ1 = 4L, f1 = v L n = 2, λ2 = 4 3 L , f1 = 3v 4L 4L one open, one closed end fn 2n 1 v 4L 2n 1 f1, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License n 1 4L 2n 1 2n 1 49 Let’s look at string oscillations between two fixed points (a classic demonstration is to have the string between a pair of small electric motors that are spinning). You can use your finger to suppress certain modes of vibration. With no finger placement, the string will usually vibrate in the first harmonic (the natural frequency). f1 = v 2L Lightly placing your finger at the middle node for the second harmonic suppresses the first harmonic, but allows the string to still oscillate in the second harmonic (the double-frequency overtone). f2 = v L = 2f1 Placing your finger at one of the nodes for the third harmonic suppresses both the first and second harmonics but allows the string to still oscillate in the third harmonic (the triple-frequency overtone). f3 = 3v 2 L = 3f1 Problem 15 A 0.72 m long string vibrates with a frequency of 780 Hz. The string has two nodes between the ends. a) Find the fundamental frequency and the other harmonics with frequencies lower than 780 Hz. b) Find the wave speed in the string. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 50 Resonance If you wet your finger and move it around the rim of a wine glass at the right speed, the wine glass will oscillate, producing an audible sound. When you introduce a wave into a string, you have to apply a force to move one end of the string back and forth. If a periodic force is applied to such a system, the amplitude of the resulting motion is greatest when the frequency of the applied force is equal to one of the natural frequencies of the system. The frequencies of the applied force that match the natural frequency of the system are known as resonance frequencies. The frequency of your voice is centered on the resonant frequency for your vocal tract. Some items vibrate with a natural frequency when struck. In a tuning fork, the natural frequency is enhanced and purified (stripped of side harmonics). A bell is another device designed for a specific natural frequency. When you drop coins on a hard floor, you can often tell if it is a penny or a loony by the sound of its natural frequency. Resonance and natural frequencies are generally avoided in most engineering projects that are not designed to vibrate. Check the internet for the amazing videos of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which collapsed rather violently during strong winds in 1940. You can also revisit http://phet.colorado.edu/new/simulations/sims.php?sim=Wave_on_a_String. With the tension set on high, frequency at 50 and damping off, you can set up a standing wave by applying the oscillation driver for a few seconds (if the amplitude gets too big, you can use the damping to reduce it). The green beads (?) mark the nodes of the standing wave. Try setting up other standing waves with and without a fixed end. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 51 BEATS Let’s look at the interference of waves of different frequencies. With different frequencies, there are no stationary spatial properties. Ignoring the spatial part, the wave functions are y1 A cos2f1t y2 A cos2f 2t and Under superposition, the combined wave function is y y1 y2 A cos2f1t A cos2f 2t Here, we use the trig rule a b a b cos a cos b 2 cos cos 2 2 to get f f f f y 2 A cos 2 t 1 2 cos 2 t 1 2 2 2 The term in square brackets is regarded as the resultant amplitude. This amplitude varies with the beat frequency f beat f1 f 2 2 The figure below shows two waves with slightly different frequencies and the superposition of the two waves. Notice how the amplitude varies as the two waves go into and out of phase. If the frequencies of the two waves are very close you can actually hear the amplitude going loud and soft with the beat frequency. y1, and y2 y amplitude Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 52 Problem 16 When Bob howls at a frequency near 230 Hz, his dog Fido will howl along with him. Calculate the beat frequency if Bob is howling at 233 Hz and Fido is howling at 228 Hz. As always, check out problems in the text as well as the problems in the assignments. By practicing problems related to oscillations and waves, you will develop an understanding of the types of questions, important factors and general method of solving. Also look for examples in real life, listen for the change in frequency of a train whistle as the train passes you. Recognise natural frequencies and simple harmonic motion around you. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 53 SUMMARY Simple Harmonic Motion d 2x cx , dt 2 x sin a cx c t , Fx kx , or v c cos c t , a c sin c t cx Wave Equation x A cost ω is the angular speed or angular frequency, A is the amplitude and is the phase v A sin t a 2 A cos t 2 x 2 T f k , m 2 2 1 1 T 2 k m for a mass m on a spring with spring constant k m k period is measured in seconds. k m 2 frequency in Hz Small Angle Approximation cos 1, sin , tan for θ < 0.1 radians Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 54 Pendulum (small angles) L g , T 2 g L for pendulum length L, acceleration due to gravity g Circular Motion x A cos t , y A sin t A cos t … note the 90 phase difference 2 2 Travelling Wave v f T wave speed x t 2 y x, t A sin x vt A sin 2 A sin kx t T displacement as a function of position and time k 2 , v k wave number k Sound v T speed of sound in a string, T is tensions, μ is linear density v 331 m/s 1 I 2 r12 I1 r22 TC 273C speed of sound in air at temperature TC ratio of intensities at different distances from sources I I 0 10 log 10 decibel sound intensity, where I0 = 10-12 W/m2. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 55 v vO f f v vS Doppler frequency, vS speed of source towards observer, vO speed of the observer towards the source Interference Depending on the path length difference (pd) between the two sources and the observer, you get constructive interference pd 2n or destructive interference pd 2n 1 f beat f1 f 2 2 n = 0, 1, 2… beat frequency Standing Wave fn nv 2 L 1 nf1 , n 2L n n fixed ends, cavity/string length L, speed v, n = 0, 1, 2… fn nv 2 L 1 nf1 , n 2L n n open ends (free ends), n = 0, 1, 2… fn 2n 1 v 4L 2n 1 f1, n 1 4L one end fixed/one end free, n = 0, 1, 2… 2n 1 2n 1 NANSLO Physics Core Units and Laboratory Experiments by the North American Network of Science Labs Online, a collaboration between WICHE, CCCS, and BCcampus is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License; based on a work at rwsl.nic.bc.ca. Funded by a grant from EDUCAUSE through the Next Generation Learning Challenges. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License 56