Group Identity and Social Trust

advertisement

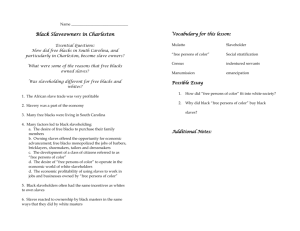

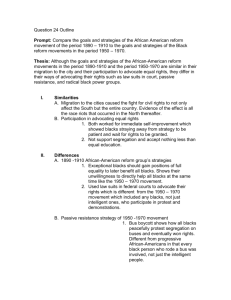

Group Identity and Social Trust in the American Public J. Matthew Wilson Southern Methodist University jmwilson@mail.smu.edu Abstract: This study considers the impact of strong identification with a social group on generalized trust in others, and hence on the formation of social capital. Previous work in the field has tended to ignore intra-group differences in levels of social trust and affect toward out-groups, which I argue are substantially rooted in orientations toward individuals’ own social groups. Using three major groups (women, African Americans, and evangelical Christians) as exemplar cases, this paper outlines the circumstances under which strong group identification is likely to contribute to or detract from generalized social trust, and demonstrates empirically its importance both for broad questions of faith in others and for attitudes toward specific out-groups. In all three cases, the strength of individual members’ identification with the social group shapes powerfully their profession of trust in their fellow citizens, and their affective responses to a range of other social groups. The findings have clear implications for our understanding of the sources and origins of social trust, the most central and crucial building block of social capital. The last decade has witnessed an explosion of social science research on the topic of “social capital.” Beginning with Coleman (1990), followed most notably by Putnam (1993, 1995, 2000), scholars have stressed the importance of civic engagement, collective problem solving, and general public-spiritedness for the health of a democratic polity. This observation is not new; over a century and a half ago, Alexis de Tocqueville (1840) observed these same virtues to be central and vital to American political culture. What is new, however, is the perception that these qualities are in short supply in the contemporary United States, and that they have declined at an alarming rate over the last several decades (Putnam 1995, 2000). This realization has led to serious scholarly inquiry into the sources of social capital, in an attempt to develop prescriptions for stemming the tide of American civic indifference. First and foremost among the factors identified as making important contributions to social capital has been trust, whether of other people, of the government, or of both (Yamagishi and Yamagishi 1994; Brehm and Rahn 1997; Berger and Brehm 1997). Only if people believe that others are basically decent, sharing on some level similar values and not seeking to take advantage of them, will they be willing to engage actively in the larger society. In game-theoretic formulations, trust is critical in inducing cooperative behavior and pareto-optimal outcomes (Axelrod 1984; Wrightsman 1992), and the same logic has been applied to real-world social and governmental settings (Levi 1997). Clearly, generalized trust is a central bedrock of social capital. The identification of trust as a prime contributor to social capital has in turn led to inquiry into the sources of social and political trust (Hardin 1993; Fukuyama 1995; Brehm and Rahn 1997; Brehm 1999). In Brehm’s (1999) characteristic formulation, trust in other people and trust in government are mutually reinforcing, and also driven by factors such as education, age, economic circumstances, and evaluations of governmental performance. Absent from this and all other 1 existing trust models, however, is any consideration of the role of group identification in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward others in society. While Loury (1977) uses the idea of social capital to explain economic empowerment in minority populations, other scholars have given remarkably little attention to the effects of individuals’ affective ties to their various social sub-groups on generalized trust.1 Clearly, a sense of close attachment to one particular segment of society (one’s own race, gender, or religious group) has the potential to shape powerfully one’s view of the larger social whole, and of other people in general. Related work in social psychology suggests strongly that group attachments shape individual perceptions of and trust in generalized others. Parenti (1967), for example, argues that ethnic communities develop powerful social and political norms that shape their members’ interactions with the larger society. Additionally, social identity theory, initially advanced by Tajfel and Turner (Tajfel and Turner 1979; Tajfel 1981; Turner 1987), holds that people define themselves socially primarily with reference to salient groups of which they are members. In this process of selfcategorization, the individual tends to develop a group-centered lens through which to view others in society (Fiske and Taylor 1991). For subordinate groups particularly, group-based norms for understanding the behavior and intentions of people both within and outside the group can significantly influence an individual member’s view of generalized others, especially if that member strongly identifies with the group in question. Dawson (1994), in his study of contemporary African American political behavior, makes use of social identity theory to explain precisely this phenomenon in the black community. Clearly, social psychological models predict widespread and powerful group-based heuristics that shape individuals’ perceptions of their relationship to the larger society. Despite these findings, however, the extant literature on social trust has largely ignored group identification as a major factor. 2 This paper employs a multi-pronged analytical approach in an attempt to remedy the omission of group identity from the discussion of social trust. After outlining the circumstances under which strong group identification could either bolster or undermine generalized social trust, I present models testing the impact of group identity on trust in other people, trust in government, and affect towards out-groups. Overall, this paper traces in some detail the interaction between identification with a particular segment of society and attitudes toward generalized others. It should provide an important enhancement and corrective to the currently prevailing models of social trust and, in turn, of social capital. Theory and Hypotheses If modern political science has largely ignored the potential relationship between attachments to a segment of society and broader social trust, it has not gone unremarked by the more philosophically inclined. Two centuries ago, Edmund Burke (1791) observed in his Reflections on the Revolution in France that "To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed toward a love for our country and for mankind." The logic here is clear: habits of trusting others and recognizing their basic decency, first developed in the context of those with whom one associates closely and shares obvious characteristics, are likely in the end to color favorably one’s view of humanity at large. Barring any unique characteristic of the group that might make its close adherents more wary and suspicious of others in society, this should be the normal pattern. “To be attached to the subdivision” should contribute to one’s “public affections;” put less elegantly, in the language of modern social science, strong group identification should normally be a significant and positive predictor of individuals’ levels of generalized social trust. Thus, racial 3 identification among African Americans and gender identification among women, for example, should increase affect towards and confidence in other people generally. Of course, this is not to suggest that under all circumstances strong group identification will result in greater generalized social trust. Organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and Aryan Nation obviously push group identity to a dangerous level, and channel it in destructive ways directed against specific (though often quite varied) out-groups. Even among more main-stream groups, however, there are circumstances under which group identity can erode social trust and social capital. This is particularly apparent among African Americans. Dawson (1994) includes in his discussion of black-white relations at least one possible future scenario in which the liberal integrationist project fails, and black identity begins to strongly undermine trust in out-groups. Orr’s (1999) study of school politics in Baltimore points out a specific instance where the fostering of black social cohesiveness and social capital has resulted in a less trusting overall orientation toward relevant actors outside the group. Likewise, Harris-Lacewell’s (1999) analysis of black ideology suggests that only for liberal integrationists in the black community should stronger in-group ties be associated with generalized social trust. For black nationalists, one of the very foci for group identity is lack of trust in those outside the group. That liberal integrationism has been the dominant paradigm for mainstream black leadership since the civil rights movement would suggest that for the most part racial identity among blacks should augment generalized social trust, but one should be aware of the separatist undercurrent in black thought as well. Nonetheless, there remains good reason to believe that, under normal circumstances, identification with one’s own social group should contribute positively to generalized social trust. To begin with, “habits of trusting” developed within the group setting should facilitate trust on a broader level. Additionally, Smith and Tyler (1997) suggest that positive feelings toward one’s own 4 group, and favorable interactions within it, build individuals’ sense of efficacy and self-esteem. As both of these characteristics have been shown to contribute to social trust and more positive orientations toward the larger society (Tyler 1997), this provides another important reason to suggest that group identity ought normally to be associated with increased generalized trust and more positive affect toward most other members of society. It is conceivable, however, that strong identification with some social groups could decrease levels of trust in generalized “others.” If a group’s central identity elements and belief set emphasize the shortcomings of non-members, one would expect group identity to detract from social trust and affect toward out-groups. This might particularly be the case with evangelical Christians, for reasons deeply rooted in the group’s central religious doctrines and worldview. From the very earliest days of American evangelicalism, evangelical theology has stressed the fundamental sinfulness of man, emphasizing that most people will make poor moral choices most of the time (Clabaugh 1974; Noll 1992). Evangelical pastors often stress the sharp distinction between “the Elect” and the great mass of humanity, mired in sin and unbelief (Guth et al 1997).2 Moreover, over the last thirty years a sense has developed among evangelicals that they are involved in a “culture war,” in which many of their fellow Americans scorn their religious faith and reject their basic values (Green et al. 1996). This perception could well serve to create a siege mentality among evangelicals with strong religious identity, undermining their generalized social trust. Thus, for reasons specific to the particular group, religious identification among evangelicals is likely to be negatively associated with professions of faith in the honesty and decency of others. This pattern, however, should be the exception rather than the rule. Under most circumstances, the previously discussed link between group identification and trust in others should apply. It is important to note that neither in the usual pattern (hypothesized to be present among 5 women and blacks) nor in the exceptional case of evangelicals is there any reason to suspect a direct link between group identification and trust in government. While some have asserted that African Americans as a group are likely to have more faith in government (at least at the national level) than are whites (Walton 1985), Brehm and Rahn’s (1997) more recent analysis does not find any such relationship, despite including race in the model of government trust. More importantly, there is no reason to suspect that strong adherents of any of these groups (women, blacks, and evangelicals) would on average differ from their low-identity counterparts in their levels of trust in government. Strong group identification may create more ambivalent feelings about government (i.e. heightened awareness of government’s potential utility in achieving group objectives coupled with increased anger at the group’s under-representation in the corridors of power), but there is good reason to remain agnostic about the overall direction of strong group identification’s effect on mean levels of government trust, and to suspect that it should in any case be rather small. Thus, we have here a relatively straight-forward set of predictions. While the strength of an individual’s group identification should have no great impact on levels of trust in government, it should clearly influence his profession of trust in other people, usually positively, occasionally negatively. What we would like to infer from this if true, of course, is that close identification with a social group affects the way that individuals think about and evaluate people in the larger society. In other words, strong identifiers should be more favorably disposed (or more hostile in the case of evangelicals) toward out-groups. There is, however, another possibility to guard against, particularly in the case of those groups with whom identity seems positively correlated with social trust. Since the battery of trust questions (on which more detail later) query about one’s evaluations of the motives of generalized “other people” or “most people,” it is possible to be deceived by a spurious relationship here. It may be the case that strongly identifying group members actually feel no more 6 warmly toward members of other groups than do weakly-identified group members. Instead, they may simply be answering the questions to a greater extent with reference to members of their own group. In other words, African Americans with high racial identity, for example, when they answer that “other people” are trustworthy, might really mean that other blacks are trustworthy. It is certainly plausible that strong group identifiers might disproportionately use their own group as a referent when answering such general questions. Clearly, if what we are ultimately interested in is trust beyond the narrow confines of a single social group, we must find some way to distinguish between a genuine increase in affect toward out-groups and a mere artifact of differing frames of reference in responding to a survey question. If strong identification with most groups does indeed enhance an individual’s tolerance, respect, and even affection for groups of which he is not necessarily a member (the true basis of social trust and broad-based social capital), then strong identifiers should provide more favorable responses when queried about a variety of social groups in the context of a survey. According to Coleman (1990) and Fukuyama (1995), generalized social trust is fundamentally a question of respect for and sense of commonality with people to whom one does not have direct ties. Thus, one key indicator of social trust would be an individual’s attitudes toward a variety of groups of which he or she is not a member. While the claim that strong group identifiers simply use a different reference group when answering the general social trust questions cannot be directly tested and refuted—one can hardly ask a respondent “Who were you thinking of when you just answered that question?”— one can examine differences between high- and low-identifiers in their evaluations of specific outgroups . If, as I maintain, strong group identification among women and African Americans is truly associated with genuinely higher levels of social trust, then high race and gender identifiers ought to express warmth towards more groups and animosity toward fewer groups than their low-identity 7 counterparts. Conversely, the pattern among evangelicals ought to be exactly opposite: those with strong religious identity ought to express affection for fewer groups and hostility towards more groups than those with low levels of religious identification.3 To recap, then, the hypotheses to be tested here are as follows: Strong group identification should significantly influence levels of social trust among all groups examined. The relationship should be positive among women and African Americans, and negative among evangelical Christians. There should be little or no direct relationship between group identity and government trust among any of the groups. Strong identifiers among women and blacks should express feelings of closeness toward more social groups than do weak identifiers. Strongly identifying evangelicals should express closeness toward fewer groups than weak identifiers. These patterns should hold even after controlling for ideology. Strong identifiers among women and blacks should express animosity toward fewer social groups than do weak identifiers. Strongly identifying evangelicals should express hostility toward more groups than weak identifiers. These patterns should also hold even after controlling for ideology. Data and Method In examining the question of group identification and social and political trust, there is a necessary trade-off between breadth and depth. One could do a highly detailed and contextual study of a single social group, or a much less detailed examination across the entire spectrum of 8 possible groups. The analysis here is based on a middle-ground approach, selecting three groups for analysis: blacks, women, and evangelical Christians. This number should allow individual discussion and analysis of each group, while at the same time providing some assurance that the findings are generalizable across different group contexts. Significantly, the selected groups vary in size (from about 12% to over half of the U.S. population), partisan disposition (from strong Democrat to strong Republican), and social integration with other groups (from generally segregated in residence, work, and worship to largely integrated in most social contexts). Thus, these groups are amenable to analysis within the theoretical framework outlined here, and an examination of them should provide a good general discussion of the relationship between group identity and social trust. Patterns found in these three groups may reasonably be considered general social and political phenomena, because of the clear diversity of the groups across a host of dimensions. The analyses here employ data from the 1992 American National Election Study.4 This survey is based on a national sample of about 2500 respondents, and contains measures of both objective group membership and group identification for all three groups of interest (discussed in greater detail below). The 1992 NES data set contains over 1300 women, over 600 evangelicals, and over 300 blacks. Thus, while the sample of African Americans is smaller than ideal, there are enough respondents in each of the three groups to permit useful within-group analysis.5 Before proceeding with a discussion of specific models, a few notes on how respondents were classified into these three groups are in order. To begin with, only people who are objectively members of the groups in question are considered in the analyses. While other people may in some sense “identify” with blacks, women, or evangelicals, this is a much different psychological phenomenon than the one examined here. This exclusion of non-members is consistent with previous work in the field, as Gurin et al. (1980) and Conover (1984) among others maintain that 9 objective membership is a prerequisite for group identification or consciousness. By this criterion, blacks and women are easily classified based simply on the race and gender questions in the NES, but evangelicals pose a bit more of a problem. While there are several possible methods for identifying evangelicals using survey data, the strategy outlined in Green et al. (1996), classifying respondents primarily according to their religious denomination, is employed here.6 This method identifies those respondents who attend evangelical churches, allowing additional sub-division, comparison, and analysis based on professed identification with the evangelical movement. Another important methodological issue is the question of how to operationalize group identification. The most common practice when using NES data is to rely on the “closeness” measures in the study (see, for example, Conover 1984). In these items, respondents are presented with a list of groups, and asked which of the groups are “most like you in their ideas and interests and feelings about things.” Blacks and women who identify these respective groups as being close to them are classified as high identifiers; those who do not select the group are considered low identifiers.7 For evangelicals, the process is somewhat more complicated, because no religious groups are on the list presented to respondents in the “closeness” battery. There is, however, a question asking Christian respondents to classify their type of Christianity as either “moderate to liberal” (the option selected by the majority of respondents) or “evangelical,” “fundamentalist,” or “charismatic or Spirit-filled.” Those respondents identified (by the process described above) as objectively members of evangelical churches are classified as high identifiers if they self-select one of the labels associated with the broader evangelical movement (that is, a description other than “moderate to liberal”). Those who do not select one of these labels are classified as low identifiers. This method of division yields approximately the same two-to-one ratio of high- to low-identifiers as the closeness battery does for blacks and women, lending some support to the contention that the 10 two methods are at least roughly comparable. There are admittedly some drawbacks to using the closeness items as a measure of the strength of group identification. To begin with, they are dichotomous, forcing a simple high-low division of identifiers instead of the more realistic continuum along which group identification almost certainly ranges. One possible remedy for this defect would be to use group feeling thermometer ratings instead, but feeling thermometers capture a slightly different theoretical concept—affect as opposed to identification. As Turner (1982) argues, “The first question determining group-belongingness is not ‘Do I like these individuals?’ but ‘Who am I?’.”8 A more important potential problem is that not all respondents necessarily understand “closeness” in the same way, making these items somewhat “noisy” measures of the underlying concept of group identification. However, the closeness measures do seem to be the best approximation available for group identification, and using them provides the clearest basis for comparison with previous work. Ultimately, if strong results emerge using this fairly blunt instrument, we may have considerable confidence that a more finely honed one would produce even sharper findings. The most important methodological issues for this analysis involve the creation of the various scales measuring social trust, government trust, and civic engagement. In all of these, I have intentionally followed other scholars’ formulations (particularly Brehm and Rahn 1997 and Brehm 1999) closely, both because their scale components seem quite plausible and because this will allow for the most direct possible comparison of my findings with theirs. The scale measuring civic engagement (a predictive variable in the social trust equation) is built from six individual items measuring individuals’ involvement or willingness to become involved in community service and activities. These activities include talking with their neighbors, performing community service, serving on a jury, and attending church, among others.9 Likewise, the government trust scale is 11 constructed from a basket of five items, measuring perceptions of the extent to which government and politicians are honest, efficient, responsive, and representative. Finally, the social trust index is built from two questions (as in Brehm 1999), measuring willingness to trust other people and perceptions that others are seeking to take advantage. Means, distributions, and standard deviations on all of these scale measures are comparable to those found in previous work. More specific details on the construction of these scales, including the wording of all of the component questions and the exact equation used to compute individual values, can be found in the Appendix. A second methodological issue involves the operationalization of affect toward various social groups. Fortunately, the NES includes a battery of questions asking individuals to provide feeling thermometer evaluations of over twenty different major groups in society, ranging from immigrants to conservatives to homosexuals to the military. Additionally, the NES closeness measures (the same ones that I use to separate high- and low- group identifiers) ask respondents whether or not they feel close to sixteen different groups, ranging from Asian Americans to Southerners to Working-class people. There are eleven groups that appear in both of these batteries, and they form the basis for my analyses in this paper. From evaluations, it is possible to derive measures (both positive and negative) of respondents’ general affect towards others in society. In this analysis, I employ two measures. One is “positively” valenced, tallying the number of groups to which individuals profess feelings of closeness.10 The other measure is “negatively” valenced, tallying the number of groups toward which respondents express clear hostility.11 A list of the groups presented in both the closeness and feeling thermometer measures can be found in the Appendix. By examining respondents’ feelings of both affection and distaste for other groups in society, I hope to provide a clear and conclusive demonstration of the effects of group identification on social trust. 12 Analysis The first stage in my analysis seeks to establish a direct connection between identification with a social group and trust in generalized others. Of course, to test fully and accurately the link between group identity and social trust requires a properly specified multivariate model. Following Brehm and Rahn (1997) and Brehm (1999), I assume the two trust functions to be reciprocally dependent processes; in other words, social and governmental trust should be mutually reinforcing. Thus, the model estimated is a two-stage least squares regression model, with separate estimations for women, evangelicals, and blacks. The independent variables are the same across all three groups.12 The social trust equation, in addition to the government trust term to specify the reciprocal relationship, contains a variety of other predictive variables. To begin with, it includes the civic engagement scale described above, based on previous scholars’ assertion that civic engagement is critical in building trust in other people (Putnam 1995; Brehm and Rahn 1997). In addition, the equation (where appropriate) includes terms for race, gender, and religion, based on the well-documented fact that blacks are less trusting of others than are whites (Walton 1985; Mullen 1991; Kramer 1994) and the suggestion from the bivariate results above that evangelicals and women might be somewhat less trusting than others. The model also includes dummy variables for several age groups (people born in the 1950’s, 1960’s and 1970’s), based on work indicating that younger cohorts in America have grown progressively less trusting and more cynical (Easterlin and Crimmins 1991; Putnam 1995; Brehm and Rahn 1997). Education, also included in the model, is thought to be correlated with greater knowledge and understanding of diverse groups of people, and hence with higher levels of social trust (Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus 1982). Personal experience of divorce is assumed to depress trust in others, while exposure to media is assumed to make a positive contribution (Brehm and 13 Rahn 1997). Finally, and most importantly, a strength of group identification term is included in the model, with directional hypotheses specific to each group as outlined above. The government trust model also follows as closely as possible the specifications employed in previous work (Brehm and Rahn 1997; Brehm 1999), with the addition of the group identity term. In addition to the social trust scale specifying the presumed reciprocal relationship, the model contains items measuring both positive and negative affect toward the two major political parties.13 Age cohort measures are also included, to capture any possible effects of coming of political age during the low-trust Vietnam and, especially, Watergate era (Berger and Brehm 1999), or during the more trusting Reagan era (Citrin and Green 1986; Miller and Borelli 1991). Ideology is included, on the assumption that conservatives, with their generally anti-statist orientation, might be more skeptical of government than liberals. Finally, a variety of government performance measures are in the model, including economic prosperity, foreign prestige, and responsiveness to public opinion, as all of these have been demonstrated to contribute significantly to individuals’ levels of trust in government (Feldman 1983; Lipset and Schneider 1987; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 1995). Results of the two-stage least squares models of social and government trust are presented in Table 1. Looking first at the model for social trust among women, we find that, as expected, trust in government makes a powerful contribution to trust in other people. Additionally, civic engagement also performs as expected, increasing the likelihood that respondents will profess trust in their fellow citizens. Black women have sharply lower levels of social trust than do white women (confirming a pattern suggested in the bivariate analysis), and young women are significantly less trusting than are older women. Education and the experience of divorce both operate as expected, augmenting and detracting from social trust, respectively. Despite some suggestions to the contrary, evangelical Christianity and exposure to news media appear to have no discernible effect on levels of social 14 trust, at least among women. Finally, and most importantly, strength of gender identification among women has a clear effect in increasing trust in other people. In this case, attachment to the genderbased group clearly translates into more positive generalized feelings toward one’s fellow citizens at large. [INSERT TABLE 1 HERE] In the government trust portion of the model, we encounter an unexpected result. Contrary to Brehm and Rahn’s (1997) argument that social trust and government trust are mutually reinforcing, the results here suggest that social trust among women actually exerts a significantly negative influence on trust in government. In other words, the more women trust their fellow citizens, the less faith they place in government.14 Other than this puzzling finding, however, the other coefficients are basically as expected. Both of the partisan affect measures exert a significant influence in the anticipated direction. Also, the youngest respondents (those born in the 1970’s, who would have become politically cognizant during the Reagan era) have slightly more confidence in government than do other women in the sample. Not surprisingly, coefficients for the government performance evaluation measures are all significantly positive. Finally, as hypothesized, there is no direct link between strong gender identification and trust in government. Group identification’s contributions to trust appear to be entirely on the social trust side of the ledger. Turning to the model of social and government trust among African Americans, we find, generally speaking, the same patterns as among women. Trust in government is a significant predictor of trust in other people, as is education. African Americans born in the 1960’s are less trusting of their fellow citizens than are other blacks in the sample, though the effects of age cohort on trust among blacks are less pronounced than they are among other groups. For African Americans, increased exposure to the news media does indeed promote social trust, albeit only to a 15 modest extent. In the government trust model, we find once again a surprisingly strong negative relationship between trust in others and trust in government (see endnote 14). Aside from that, the only significant predictors of trust in government are the positive partisan affect measure (though not the negative one), and the various governmental performance evaluations. Most importantly, the terms measuring strength of racial identification perform exactly as hypothesized in both portions of the model: exerting a positive influence on trust in other people, and playing no direct role in individuals’ trust in government. Thus, on the variables of theoretical interest, the patterns observed among African Americans are completely in line with those found among women. In the trust models for evangelicals, we again find confirmation of the central hypotheses. Trust in government, civic engagement, and education all promote social trust among evangelicals, just as they do among women and African Americans. Evangelicals born in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s are all significantly less trusting of others than are older evangelicals. Results of the government trust model also look very much like those among women and blacks (though here the effect of social trust, while again negative, is not statistically significant). Both positive and negative affect toward the political parties are significant, and in the expected directions. Likewise, government performance evaluations again make important contributions to government trust, though curiously only two of the four (economic performance and responsiveness to public opinion). Clearly, though, the coefficients of greatest theoretical interest are those for the terms measuring strength of religious identification. Here, the unique, group-specific hypothesis regarding evangelicalism and social trust is strongly supported. Evangelicals with high levels of religious identification are significantly less likely to profess trust in generalized “others” than are evangelicals with weaker religious identifications. Once again, the effect is only present in the social trust portion of the equation; the impact of religious identification on trust in government is nil. 16 There is strong evidence in all three of these models that identification with a social group shapes individuals’ attitudes toward others in important ways, usually building social trust, sometimes undermining it. To be sure that we have captured a true component of social capital, however, it is important to confirm that this result does indeed reflect an altered disposition toward others (particularly out-groups), rather than simply a different frame of reference in answering the trust questions. To explore this question in greater depth, I turn to the previously discussed analysis of individuals’ professed closeness and distaste for various groups of people in society. The results here, it is hoped, should mirror and confirm those in the social trust models above, with group identification promoting greater overall positivity toward other groups among women and blacks, and greater negativity among evangelicals. Table 2 presents OLS models of both the number of close groups and the number of disliked groups for women, blacks, and evangelicals.15 Because, as I argue, these affect measures are closely related to generalized social trust, they should stem from common sources. Thus, these models contain the same independent variables as the social trust models presented in Table 1, plus a control for ideology. This ideological variable is important, because one could argue that the list of groups presented is “biased,” in the sense that it contains more groups likely to be objectionable to conservatives (and hence evangelicals) than groups likely to offend liberals. My objective here is not to comment on the relative “tolerance” of blacks and whites, men and women, liberals and conservatives, or evangelicals and others—I am, for purposes of my argument in this paper, agnostic on these points. If, however, there truly is a relationship between group identification and social trust, strong identity should clearly influence affect toward other groups, either in positivity (closeness), negativity (dislikes), or both, even after controlling for any ideological skew in the list of groups to be evaluated. 17 Turning first to the models among women, we find strong evidence of this pattern. In the close groups model, civic engagement is an important predictor—those respondents who are involved in their communities profess closeness to significantly more groups of people than do those who are more disengaged. Additionally, black women, evangelical women, and younger women score higher on this measure than do other women in the sample.16 Most importantly, strength of gender identification plays a strong role in shaping women’s feelings of closeness toward other groups. Those who feel close to other women are likely to feel close to more other groups as well. This same general pattern of results is reflected in the model of disliked groups, though of course in the opposite direction. Here, government trust is highly significant; those women with high levels of confidence in government express negativity toward significantly fewer groups than do those who do not trust government. As expected, the ideology term is significant, as conservative women dislike more groups on average than do liberal women (probably a product of the slight ideological skew of the groups presented for evaluation). Younger and more educated women, not surprisingly, dislike fewer groups than older and less well educated women. Finally, the group identity term is significant here as well, with strong gender identification resulting in significantly less hostile evaluations of other groups. Thus, among women, gender identification powerfully shapes feelings toward out-groups, both increasing feelings of closeness and decreasing expressions of hostility. [INSERT TABLE 2 HERE] Generally speaking, the results among African Americans are similar. Civic engagement is once again a predictor of the number of groups to which a respondent professes closeness, just as it is among women. Most important, however, is the impact of the group identity term. Strong racial identity among African Americans has a dramatic impact on professions of closeness to other 18 groups. Black respondents with high levels of racial identification express closeness to 2.3 more groups, on average, than those blacks with low levels of racial identification, controlling for all of the other factors in the model. Turning to the model of disliked groups, however, we find a somewhat different situation. Here, just as in the model among women, government trust and youth are negatively correlated with professions of hostility towards other groups in society. The coefficient for the group identification term, however, while in the right direction, is not significant. It therefore appears that, for African Americans, group identity’s contribution to social trust comes primarily from its very powerful effect on feelings of closeness toward other groups (positive affect). The final set of models presented here are those for group affect among evangelicals. Here, of course, we expect group identity to work in exactly the opposite way from its effects among women and blacks, decreasing expressions of closeness to other groups and/or increasing expressions of hostility. In the close groups model, there is no evidence of an effect from religious identity. Just as among women and blacks, the extent of an individual evangelical’s civic engagement is strongly correlated with closeness to other groups in society. In addition, level of exposure to media contributes to expressions of closeness. There is, however, no discernible effect of religious identification in this model. Turning, on the other hand, to the analysis of disliked groups, we find a much different pattern. As with women, the ideology term is significant, indicating that liberal evangelicals dislike fewer groups than conservative ones. Additionally, it appears that, among evangelicals, being female is correlated with greater affect for out-groups, as is being divorced.17 Of greatest importance, however, is the effect of strong religious identification. Evangelicals with high levels of religious identity express hostility, on average, toward .2 more groups than do their low-identity counterparts. When the average respondent expresses hostility toward less than 1 group, an increase of this magnitude is quite a jump. Thus, once again, the link 19 between group identification and social trust established in the earlier models is borne out in the analysis of affect toward out-groups. The claim that evangelical identity has negative effects on social trust is bolstered by this evidence of its contribution to increased hostility toward other social groups. Discussion The analysis presented here suggests an important link between close identification with a major social group of which one is a member and more universal feelings of trust and affection toward other individuals in society at large. In all three of the groups examined, strength of group identity plays a central role in shaping members’ attitudes toward generalized “others” and, relatedly, toward members of specific out-groups. The effects of group identity do not always run in the same direction; while the “normal” pattern, observed among women and blacks, is consistent with Burke’s assertion that attachment to the subdivision should serve as the “germ of public affections,” there is also the important case of evangelicalism in which religious identity serves to undermine faith in the general goodness of the larger society. What is clear, however, is that across the board, measuring and understanding individuals’ attachments to social groups is indispensable if we are to explain completely the sources of their social trust (or lack thereof). These results have implications for the larger question of social capital as well. If the pattern observed among women and African Americans, where strong group identification seems to promote more positive feelings about others in society, is indeed the norm, then there is reason to believe that strengthening the salience of such categories to their members could result in increased social capital. One must, however, be cautious about pushing this conclusion too far. There is a fine line between a positive, desirable group identification that enhances the social fabric, and a 20 socially destructive one that regards non-members as irrelevant at best and as adversaries at worst. The evidence presented here, however, suggests that currently, group identification (at least among women and African Americans) is not a zero-sum game; increasing commitment to a segment of society does not come at the expense of faith in the larger social whole, but rather serves to augment it.18 In the final analysis, it is clear that group identification can no longer be ignored in the discussion of individuals’ attitudes toward the larger society. As in so many areas of political science research, scholars examining social trust have tended to focus on the individual in relation to the social whole, ignoring the vital role played by an intermediate level of aggregation, the social group. As I have demonstrated here, groups through their orientation toward the larger society have the capacity to influence powerfully the social attitudes of those members that strongly identify with them. Their importance for social trust and affect toward out-groups rivals that of such well-known factors as education, age, and personal life experiences. Clearly, attachment to the social group is an important road by which individuals can be led toward (or away from) “a love for [their] country and for mankind.” 21 TABLE 1 2SLS Models of Social and Government Trust Social Trust Models Variable Women Blacks Evangelicals Constant Government Trust Civic Engagement Female Black Evangelical Born 1950s Born 1960s Born 1970s Education Divorced Media Exposure High Group ID 0.126 (0.074) ** 0.690 (0.189) *** 0.206 (0.062) *** -----0.301 (0.040) *** 0.007 (0.032) -0.025 (0.035) -0.153 (0.039) *** -0.304 (0.064) *** 0.058 (0.009) *** -0.108 (0.040) *** 0.003 (0.003) 0.055 (0.028) *** -0.140 (0.131) 0.379 (0.255) * -0.041 (0.104) -0.017 (0.048) ---------0.016 (0.060) -0.098 (0.063) * 0.099 (0.108) 0.071 (0.018) *** 0.080 (0.070) 0.009 (0.006) * 0.087 (0.067) * 0.121 (0.100) 0.735 (0.253) *** 0.266 (0.092) *** 0.040 (0.041) ---------0.100 (0.053) ** -0.126 (0.055) ** -0.179 (0.010) ** 0.067 (0.015) *** -0.064 (0.059) 0.003 (0.005) -0.092 (0.043) ** Government Trust Models Variable Women Blacks Evangelicals Constant Social Trust Pos Affect for Parties Neg Affect for Parties Female Black Evangelical Born 1950s Born 1960s Born 1970s Ideology Personal Finances Govt Econ Perf US Position in World Govt Responsiveness High Group ID 0.216 (0.045) ** -0.119 (0.068) ** 0.001 (0.000) *** -0.002 (0.000) *** -----0.024 (0.028) -0.015 (0.015) 0.010 (0.016) 0.001 (0.021) 0.044 (0.034) * -0.002 (0.004) 0.005 (0.006) 0.027 (0.008) *** 0.025 (0.009) *** 0.042 (0.006) *** 0.014 (0.014) 0.034 (0.078) -0.252 (0.165) ** 0.002 (0.001) ** 0.000 (0.001) -0.003 (0.030) --------0.003 (0.038) 0.005 (0.040) 0.040 (0.067) 0.011 (0.010) 0.019 (0.014) * 0.078 (0.018) *** 0.039 (0.021) ** 0.031 (0.014) ** 0.025 (0.048) 0.112 (0.044) *** -0.030 (0.080) 0.001 (0.000) *** -0.001 (0.000) ** -0.006 (0.018) --------0.026 (0.022) 0.010 (0.025) 0.033 (0.045) 0.005 (0.006) 0.003 (0.009) 0.033 (0.011) *** 0.011 (0.013) 0.044 (0.008) *** 0.009 (0.019) N = 816 (women), 192 (blacks), 398 (evangelicals) R2 (Social Trust) = .19 (women), .15 (blacks), .18 (evangelicals) R2 (Government Trust) = .18 (women), .27 (blacks), .28 (evangelicals) 22 *** p < .01, one-tailed test ** p < .05, one-tailed test * p < .10, one-tailed test TABLE 2 OLS Models of Affect for Other Groups Close Groups Models Variable Women Blacks Constant Government Trust Civic Engagement Ideology Female Black Evangelical Born 1950s Born 1960s Born 1970s Education Divorced Media Exposure High Group ID 0.730 (0.271) *** -0.182 (0.288) 0.759 (0.236) *** -0.073 (0.041) ** ----1.142 (0.162) *** 0.339 (0.130) *** 0.291 (0.134) ** 0.347 (0.147) *** 0.376 (0.243) * 0.015 (0.036) 0.006 (0.154) 0.046 (0.220) 0.974 (0.109) *** 1.493 (0.737) ** -0.829 (0.712) 0.947 (0.597) * -0.045 (0.100) -0.155 (0.280) --------0.325 (0.350) 0.116 (0.369) 0.184 (0.605) -0.211 (0.095) ** -0.090 (0.390) 0.036 (0.068) 2.347 (0.409) *** Evangelicals 0.705 (0.473) * 0.036 (0.508) 1.036 (0.411) *** 0.019 (0.078) -0.280 (0.184) * --------0.182 (0.234) 0.223 (0.250) 0.154 (0.459) 0.066 (0.064) 0.144 (0.264) 0.093 (0.037) *** 0.301 (0.238) Disliked Groups Models Variable Women Blacks Evangelicals Constant Government Trust Civic Engagement Ideology Female Black Evangelical Born 1950s Born 1960s Born 1970s Education Divorced Media Exposure High Group ID 0.771 (0.192) *** -0.829 (0.204) *** 0.140 (0.167) 0.073 (0.029) *** -----0.005 (0.114) -0.071 (0.092) -0.046 (0.095) -0.096 (0.104) ** -0.151 (0.172) * -0.038 (0.026) * -0.149 (0.109) * -0.002 (0.016) -0.170 (0.077) ** 1.248 (0.376) *** -0.927 (0.363) *** -0.255 (0.304) -0.020 (0.051) 0.172 (0.143) ---------0.058 (0.178) -0.313 (0.188) ** -0.135 (0.308) -0.044 (0.048) -0.155 (0.199) -0.025 (0.034) -0.104 (0.208) 0.120 (0.266) -0.655 (0.285) ** -0.086 (0.230) 0.126 (0.044) *** -0.170 (0.103) ** --------0.083 (0.131) 0.053 (0.140) -0.383 (0.258) * -0.085 (0.036) *** -0.349 (0.148) *** 0.028 (0.027) 0.171 (0.106) ** N = 864 (women), 191 (blacks), 365 (evangelicals) R2 (Close Groups) = .18 (women), .19 (blacks), .07 (evangelicals) R2 (Disliked Groups) = .05 (women), .08 (blacks), .11 (evangelicals) 23 *** p < .01, one-tailed test ** p < .05, one-tailed test * p < .10, one-tailed test Appendix: Scale Components for Trust and Group Affect Measures Civic Engagement Scale Components 1). Many people say they have less time these days to do volunteer work. What about you, were you able to devote any time to volunteer work in the last twelve months? 2). Do you have any neighbors that you know and talk to regularly? About how many? 3). If you were selected to serve on a jury, would you be happy to do it, or would you rather not serve? 4). In the last twelve months, have you worked with others or joined an organization in your community to do something about some community problem? 5). Do you belong to any organizations or take part in any activities that represent the interests and viewpoints of (Group X)? 6). Do you go to religious services more than once a week, once a week, almost every week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, or never? Social Trust Scale Components 1). Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people? 2). Would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful, or that they are mostly just looking out for themselves? Government Trust Scale Components 1). How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is right—just about always, most of the time, only some of the time, or none of the time? 2). Do you think that people in government waste a lot of the money we pay in taxes, waste some of it, or don’t waste very much of it? 3). Would you say the government is pretty much run by a few big interests looking out for themselves or that it is run for the benefit of all the people? 4). Do you think that quite a few of the people running the government are crooked, not very many are, or do you think hardly any of them are crooked? 5). How much do you feel that having elections makes the government pay attention to what the people think—a good deal, some, or not much? Groups Included in “Close Groups” and “Disliked Groups” Measures Poor People Blacks Southerners Hispanic-Americans Asian-Americans Labor Unions Business People Whites Liberals Feminists Conservatives 24 Notes A partial exception would be Dawson’s (1994) brief discussion of various possible scenarios for future black-white relations and black social trust. Also, most scholars do include a race variable in their social trust models, to account for the fact that blacks overall are less trusting than whites. However, any consideration of intra-racial differences in trust (based on levels of racial identification), or of variations in trust according to religious and gender identity, is absent in existing scholarship. 1 This reference to “the Elect” is not meant to imply a specifically Calvinist coloration to the argument. While this particular language comes from the Calvinist tradition, the general emphasis on the pervasiveness of sin and depravity is common in evangelical churches of all lineages. 2 Of course, one must be careful that an ideological bias in the selection of social groups presented does not create a spurious effect. Thus, it is important to control for respondent ideology in a multivariate context when analyzing the effects of group identity on the number of close and disliked groups. This precaution is taken here, and is described more fully later in the paper. 3 While more recent NES presidential election-year data (from 1996) are available, the 1992 data are preferable for two important reasons. First, the sample is considerably larger, including 2500 respondents (vs. 1700 in 1996). This is particularly valuable in increasing the size of the African American sub-sample. Additionally, the 1992 study has much better items on gender issues, including various measures of feminist identification that are absent in the 1996 study. Running the same basic models using the 1996 data confirms all of the major findings presented here, and results are available from the author. 4 The relatively small sample size of African Americans, while common to nearly all major national surveys, is nonetheless troublesome. One solution to this problem is to use the 1996 National Black Election Study, with a sample of over 1000 African Americans, for analyses of black racial identity. However, because the questions, interview contexts, and sample frames in the NES and NBES are not directly comparable, only NES data analysis is presented here. Thus, results presented for blacks must be seen as somewhat tentative, with large standard errors possibly attenuating significant results. 5 It should be noted that this classification method essentially excludes blacks from being classified as evangelicals. This is consistent with the general practice among scholars of religion and politics, who maintain that the black church, despite some similarities in worship style with white evangelicals, is really sui generis, deserving its own classification. 6 In both cases, the proportion of high to low identifiers is around two to one, a bit lower for women and a bit higher for blacks. 7 In reality, however, the two concepts are closely linked. In practice, when both closeness measures and feeling thermometer ratings are available, they can generally be used interchangeably without substantially altering the empirical results. 8 25 For this and the other scales discussed here, all of the components used to construct the scale load on a single factor, with all loadings at least .3, and most in the .5-.7 range. 9 With both this measure and with the “negative” tally, feelings toward the definitional membership group itself, as well as clearly related groups, are excluded. Thus, evaluations of “blacks” are not tallied for African Americans, and evaluations of “feminists” are omitted for female respondents. These omissions allow for a much clearer assessment of the attitudes of strong identifiers in the three groups in question toward genuinely “other” groups. 10 The threshold for “clear hostility” on the feeling thermometer has been (somewhat arbitrarily) set at scores of less than 25. Choosing a different threshold (20, 35, or 50), however, does not significantly alter the results presented in these analyses. 11 The model specification employed here borrows liberally from Brehm (1999), largely because he models the same processes using essentially the same data. The critical difference, of course, is my inclusion of the group identification terms in the models, and my division of the sample into three sub-populations (women, evangelicals, and blacks). 12 The positive affect measure is equal to the the respondent’s feeling thermometer rating of the Democratic party minus 50 (with a minimum of 0) plus the feeling thermometer rating of the Republican party minus 50 (with a minimum of 0). The negative affect measure is equal to 50 minus the respondent’s feeling thermometer rating of the Democratic party (with a minimum of 0) plus 50 minus the rating of the Republican party (with a minimum of 0). Thus, both scales run from 0 to 100, with 100 representing maximum affective positivity (or negativity) toward the existing political system. This approach is very much analogous to Brehm’s (1999) measure of positivity or negativity toward the major presidential candidates, but I believe that feelings toward parties are a somewhat broader indicator of general affect towards the system. 13 The reason for this difference from Brehm and Rahn’s work (and the similar race-based discrepancy to be discussed later) is not immediately apparent. It is possible that the mutually reinforcing relationship that they find between social and government trust is driven by the white male portion of the sample. Indeed, in my own analysis I find, like Brehm and Rahn, that there is a positive reciprocal relationship when one examines the entire sample, and a much stronger positive reciprocal relationship when one looks at white males only. There are many possible explanations for this race- and gender-based discrepancy, but a thorough examination of it is beyond the scope of this study. In any event, it is an interesting avenue for future analysis. 14 It is important to remember that these numbers represent tallies of the groups toward which the respondent professes closeness excluding the group in question itself and clearly related groups (e.g. women and feminists). Thus, the real differences in mean number of close groups between highand low-identifiers (at least for women and blacks) are actually greater than what is reflected in the table, since professed closeness to women or to blacks is itself the factor used to separate strong from weak identifiers. 15 26 This result, particularly for black women, is a bit surprising, given the fact that in general blacks are much lower in social trust than are whites. While the other major predictive variables (civic engagement, education, and group identity) work similarly in the social trust and group affect models, this racial variable clearly does not. This discrepancy, however, should not distract from the fact that the relationship between group identity and the various social trust indicators among African Americans is consistent and strong across the two types of models. 16 The reason for this effect, and for divorce’s correspondingly negative effect on expressions of hostility toward other groups among evangelicals, is not clear. Perhaps evangelical churches that are more accepting of divorce also differ doctrinally and culturally in other ways, resulting in more generally positive attitudes toward out-groups. This answer, however, is only speculative. 17 Of course, one can certainly question the implicit assumption here that social trust should be regarded in all cases as an unalloyed good. Evangelicals, for example, might argue that cheerful acquiescence in a morally deficient social order, or naïve confidence in people who are fundamentally self-serving, are not goals to strive for. Likewise, black nationalists would argue that racial identity among African Americans should result in more wariness toward the white power structures that work to the detriment of black interests. 18 27 References Axelrod, Robert. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York, NY: Basic Books. Brehm, John. 1999. “Who Do You Trust? People, Government, Both, or Neither?” Paper presented at the Duke University International Conference on Social Capital and Social Networks (Durham, NC). Brehm, John, and Mark Berger. 1997. “Shocks to Political Confidence and the Durability of Social and Political Trust.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association (Chicago, IL). Brehm, John, and Wendy Rahn. 1997. “Individual-level Evidence for the Causes and Consequences of Social Capital.” American Journal of Political Science 41: 999-1023. Burke, Edmund. 1791. Reflections on the Revolution in France. London, UK: J. Dodsley. Citrin, Jack, and Donald Phillip Green. 1986. “Presidential Leadership and the Resurgence of Trust in Government.” British Journal of Political Science 16: 431-453. Clabaugh, Gary K. 1974. Thunder on the Right: The Protestant Fundamentalists. Chicago, IL: NelsonHall Company. Coleman, James S. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Conover, Pamela Johnston. 1984. “The Influence of Group Identification on Political Perception and Evaluation.” Journal of Politics 46: 760-785. Dawson, Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Easterlin, Richard A., and Eileen M. Crimmins. 1991. “Private Materialism, Personal SelfFulfillment, Family Life, and Public Interest.” Public Opinion Quarterly 55: 499-533. Feldman, Stanley. 1983. “The Measurement and Meaning of Trust in Government.” Political Methodology 9: 341-354. Fiske, Susan T., and Shelley E. Taylor. 1991. Social Cognition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Fukuyama, Francis. 1995. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York, NY: The Free Press. Green, John C., James Guth, Corwin Smidt, and Lyman A. Kellstedt. 1996. Religion and the Culture Wars: Dispatches from the Front. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. 28 Gurin, Patricia, Arthur Miller, and Gerald Gurin. 1980. “Stratum Identification and Consciousness.” Social Psychology Quarterly 43: 30-47. Guth, James L., John C. Green, Corwin E. Smidt, Lyman A. Kellstedt, and Margaret M. Poloma. 1997. The Bully Pulpit: The Politics of Protestant Clergy. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Harris-Lacewell, Melissa Victoria. 1999. Barbershops, Bibles, and B.E.T.: Dialogue and the Development of Black Political Thought. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Political Science, Duke University. Hibbing, John R., and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse. 1995. Congress as Public Enemy: Public Attitudes Toward American Institutions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Kramer, Roderick M. 1994. “The Sinister Attribution Error.” Motivation and Emotion 18: 199-230. Levi, Margaret. 1997. Consent, Dissent, and Patriotism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Lipset, Seymour Martin, and William G. Schneider. 1987. The Confidence Gap. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Loury, Glen. 1977. “A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences.” In Women, Minorities, and Employment Discrimination (ed. Phyllis A. Wallace and Anette M. LaMond). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Miller, Arthur H., and Stephen A. Borrelli. 1991. “Confidence in Government during the 1980s.” American Politics Quarterly 19: 147-173. Mullen, Brian. 1991. “Group Composition, Salience, and Cognitive Representations: The Phenomenology of Being in a Group.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 27: 297-323. Noll, Mark A. 1992. A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. Orr, Marion. 1999. Dilemmas of Black Social Capital: School Reform in Baltimore, 1986-1998. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Parenti, Michael. 1967. “Ethnic Politics and the Persistence of Ethnic Identification.” American Political Science Review 61: 717-726. Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Putnam, Robert D. 1995. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6: 65-78. 29 Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Smith, H. J., and Tom Tyler. 1997. “Choosing the Right Pond: The Influence of the Status and Power of One’s Group and One’s Status in that Group on Self Esteem and GroupOriented Behavior.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 33: 146-170. Sullivan, John L., James Piereson, and George E. Marcus. 1982. Political Tolerance and American Democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Tajfel, Henri. 1981. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel, eds., The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1840. Democracy in America. Tr. Henry Reeve. London, UK: Saunders and Otley. Turner, John C. 1982. “Towards a Cognitive Redefinition of the Social Group.” In Henri Tajfel, ed., Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Turner, John C. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. Tyler, Tom R. 1997. “Why Do People Rely Upon Others?: Social Identity and the Social Aspects of Trust.” Paper presented at the Russell-Sage Workshop on Trust (New York, NY). Walton, Hanes. 1985. Invisible Politics: Black Political Behavior. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Wrightsman, Lawrence S. 1992. Assumptions about Human Nature. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Yamagishi, Toshio, and Midori Yamagishi. 1994. “Trust and Commitment in the United States and Japan.” Motivation and Emotion 18: 129-166. 30