January 10, 2007 - Geoff Anderson Materials

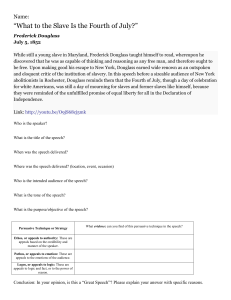

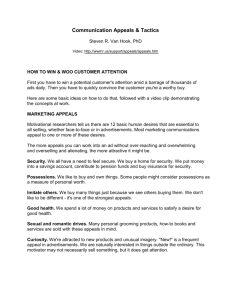

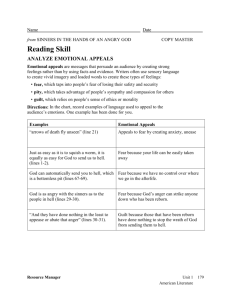

advertisement