the study of Arupa

advertisement

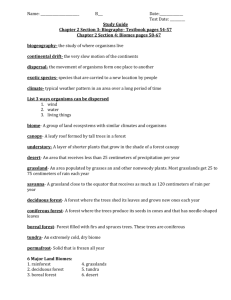

Teak plantations and Perhutani in Java Written by Anu Lounela1 Perum Perhutani is state forestry company that operates mainly in Java, in Indonesia. Perum Perhutani as a state company (BUMN) was founded in 1972 consisting of two units, Unit I in Central Java and Unit II in East Java. Later in 1978 Perhutani was added with Unit III in West Java and Banten. The role of Perhutani as the legal right holder to manage the production forest in the state forest area is recognized by the state law (PP 20/2003). The state forest area in Java covers 23/24 percent of the island. Production forest is managed by Perum Perhutani, while protection forest is managed by the Ministry of Forestry. Perhutani Province Production forest Total: 1 767 304 ha 546 290 ha 809 959 ha Unit I (20KPH) Central Java Unit II (23 East Java KPH) Unit II (14 West Java + 411 055 ha KPH) Banten Source: Perum Perhutani: Company profile 2006. Protection forest Total: 658 902 84 430ha 326 520ha Total: 2 426 206 630 720ha 1 136 479ha 247 952ha 659 007ha The island of Java 126, 700 km2 from which 14 percent is covered with forest. Central Java is about 32,5 million km2, East Java 47 million km2 and West Java with Banten almost 44 million km2.2 There are 57 administrative units (KPH) in Perhutani. Since 2005 these forest management units have been separated from Perhutani’s business unit (KBM). Each of the Unit is directed by the head of the unit, and each of the KPH is directed by administrator. The business unit has its own management and director. In general production forest has been divided into two forest categories: teak forest and rimba or “jungle” forest.3 The dominant tree species are teak and pine trees. According to Perhutani statistics, the teak forest area covers 51, 73 percent that is 1 240 558 hectares, and the pine tree forest 35, 14 percent that is 859 300 hectares. Other tree species forests cover les than five percent and include such tree species as mahogany, damar, white tree, sengon, meranti, acasia, sonokeling, kesambi, and payau. For Perhutani, teak offers 70 percent of its income. 1 This report was commissioned by Milieudefensie. It has been done in cooperation with Saleh Abdullah, Dony Hendro and Teguh Santoso who conducted field interviews and surveys in Java. Interviews were conducted in Jakarta (Perum Perhutani), Randublatung, and Yogyakarta. The cooperation included getting data from AruPa. 2 www.indonesia.go.id; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Java 3 This division goes back to 1874. There is 396 985 hectares of deforested land in the production forest area. These lands are under reforestation program that should be end by 2010. However, from that area 40 358 hectares is estimated to remain empty land since it is either covered with stones (berbatu) or there are land conflicts going on. According to Perhutani’s own estimation, in 2000 there was 1,714 million hectares in bad condition or in need of some kind of reforestation in its own production forest area.4 Perum Perhutani is working rehabilitating forest areas with 100 000 hectares per year. Perum Perhutani employs 32 035 people officially. There are about six million people in Java that are somehow involved in Perhutani labor markets or forestry practices.5 Problems with teak plantations in Java Land conflicts The most important tree specie plantations are also the most problematic in Java. Teak plantations have special history since the teak is specie that has been growing in the natural forest in Java already before the Dutch arrived in 1601. In the Dutch colonial period (16011945) the government of Holland started to use teak as in big quantities for ship building and so. During the British period 1811-1817 the colonial power under the leadership of Daendels started to build teak plantations, and formed Dienst van het Boschwezen or Jawatan that worked until 1960. The forestry Company Jawatan controlled the access to forest, with often harsh means: people were not allowed to cut trees from the plantation areas or they would be imprisoned. At the same time it used local peasants as daily laborers, often without payment. Since 1961 PN (state Company) Perhutani was formed, and reformed to Perum Perhutani in 1972 and 1978. Most of the teak forest areas locate in East Java. However, Central Java is more known for good quality teak timber. Because of the high value of teak timber, the conflicts have been extreme in the sense of open violence and clashes in the plantation areas after the 1998. According to the data by AruPa (newspaper clippings and Arupa’s own fieldwork surveys 6) there were 24 people shoot or tortured to death by Perum Perhutani between the years 1998 and 2005. There have been at least two torture cases in 2006, and all together 47 torture cases between the years 1998-2006.7 There are also cases when villagers have attacked Perhutani officials or burned their buildings or cut teak trees in mass action, especially in 1998-2000. 8 Central Java is one of the most important teak production areas in Java. However there have also been most severe conflicts between the local people and Perum Perhutani. When looking at the map of conflicts between local people and Perhutani in 2003-2006 most of them locate in Central Java (Randublatung, Rembang Semarang, Blora, to mention some). 4 Guciano, Marison, Kompas 28.4.2006. Directorate Perum Perhutani 1.5. 2007. Power point presentation. 6 See appendix 1 and 2 7 One has to note that there must be much more cases since these are only cases known by the media or Arupa staff. 8 See Java Pos, 19/06/2001 5 In the Randublatung KPH area where some of the most violent conflicts have occurred people have the view that land is not Perum Perhutani’s land. According to the local custom, land belongs to God and forest villagers are the children of Prophet Adam. It has always been the mandors who strip the forests. If people take any trees they will be caught by mandors and Perhutani staff. So how can we take trees? We have to face rifles too. If we ask for land for our use, we have to go to mandor, he asks money, and sometime he asks teak trees. 9 The villagers in Randublatung say that if there is land conflict it is the conflict of Perhutani, since Javanese have lived in the area hundreds of years and there is no way Perhutani can claim right to the land. For that reason and because their forefathers planted the teak trees, forest farmers feel they have right to take fire wood or wood to build their houses from the forest that Perum Perhutani categorizes as state forest land.10 Perum Perhutani labels the villagers as thieves when they take teak trees. Villagers consider trees as something anybody may use for fire wood or construction material; that is their traditional way. In an interview in the village in Randublatung some villagers told that seven of their fellows have died because of the conflicts. Sometimes they are hit by forest police if not tortured. In 1998, farmers told, there were two people shoot to death, and one seriously injured.11 The conflicts become violent especially when Perhutani uses such forces as Brimob (Mobile Brigade) that is know for its violent means everywhere in Indonesia. In 1998 brimob was called to control locals in Randublatung and two people died because shot in their backs. There were further cases when farmers were caught by forest guardians (waker) and severely tortured in 2000 and 2002.12 In 2003 one person died: “Musri and four friends cut teak in block (petak)26 RPH Sugih BKPH KPH Randublatung. In this state forest area Musri was also shot to his leg by Brimob patrol and forest police (polhut). The news were heard by his family: Musri has been shot! Four hours after that the family went to the hospital. Musri had already died leaving behind his wife who was in three months pregnancy. In the autopsy they saw that Musri had been shot twice in the leg, and back of his head had marks. What caused Musri’s death? Because running out of blood? Because he was hit to his head from behind? Musri felled?Because Musri was shot and he fell and back of his head was touched by something hard. There was no autopsy report and family did not know what to do.”13 On the other hand in 1998 one mandor was heavily wounded, some houses of Perhutani staff were burned.14 The conflict is unsolvable as long as Perhum Perhutani wants to guard the teak trees from the villagers who have very different understanding of property rights 9 Interview with three members of local forest group 22.5.2007, Randublatung. Teguh Santoso and Dony Hendro. 10 Trees were mostly planted before Perhutani by Jawatan, but inherited by Perhutani since the state forest area has been the same while the forestry institution was changed by the end of fifties. 11 Interview with three members of local forest group 22.5.2007, Randublatung. Teguh Santoso and Dony Hendro. 12 Ibid. 13 Dony Hendro, report from Randublatung. Case was published in the local forest group in 2003. 14 Interview with X, Perhutani staff. 22.5.2007, Randublatung. Teguh Santoso and Dony Hendro According to law Perum Perhutani may arrest so-called thieves in the forest area, but it can only hand the person over to the police forces. However, since the corrupted police forces and their slow actions, some Perhutani staff have taken law in their own hands with physical punishments. This of course breaks the law. In the company profile (2006) Perum Perhutani proudly exclaims that it will guard the forests with persuasive, repressive and preventive means. The photograph shows Perhutani’s forest police (polhut) forces with machine pistols as ready to shoot. In an interview upper staff of Perhutani said the company have difficulties to control all its 32 000 staff. Some mandors (field staff) work independently and take part of the salary money to their own pockets or are involved in illegal loggings. The same seems to go with how mandors sometimes deal with villagers in guarding the forests.15 Illegal loggings In Oct. – January 2006 Perum Perhutani suffered 17, 99 billion rupiah loss because of illegal loggings, which anyway is less than in 2005 when Perhutani lost 36, 46 billion rupiah. Most often the trees stolen are 10-20 cm teak trees.16 Between the years 1997-2000, 23 percent of the state forest cover area was lost.17 Why are trees taken without permission from the teak plantations? There are 5617 villages surrounding state forest areas in Java and about 21 million people who are dependent on forest products. Since the growing population density, lack of other livelihoods, customary tenure systems and property right conception people consider they have right to take trees to their own use. This is not “illegal logging” but it is conflict over tenure system and land rights. Villagers have built their houses from teak trees in a knock-down method already centuries. When the children of the house move, part of the house is removed and rebuilt. Perhutani staff sees that as a way to hide stolen logs.18 The amount of trees taken by the villagers is small.19 According to the research by AruPa group of blandong (teak tree thieves) consists of about 8-10 men from which 2 are spies (often children). They may take only 1-3 teak trees per month. In their calculation that means that in 1999 there would have been about one million people involved in tree theft. Normally timber traders buy legal wood with demanded letters from Perhutani and then mix it with illegally bought logs. The timber is bought from the storage places (TPK) that are along the main roads and taken from there to the wood processors or furniture business. It is impossible to say what is from legal and what is from the illegal source. The teak demand is much higher than the supply in Central Java.20 It has been estimated that wood industries in Java need 6 million cubic meters/year, and they can get only 2,9 million cubic meter from legal sources. The rest comes outside of Java or from illegal sources.21 According to tempo newspaper, 40 percent of the teak forests was lost by 2006 in Randublatung due to illegal loggings. Perum Perhutani has 80 forest guardians for about 32 000 hectares in the Radublatung KPH, in Blora, Central Java.22 The problem is that 15 Anonymous staff of Perhutani, Jakarta.Interview by Saleh Abdullah. 1.5.2007. Duta Rimba, ed.9, Th.1/ 30 Oktober-30 November 2006 17 AruPa, Rama Astraatmaja. 18 Anonymous staff of Perhutani, Jakarta.Interview by Saleh Abdullah. 1.5.2007. 1.5.2007 19 Both AruPa and Perhutani has the same opinion on this. 20 Kompas, 26.5.2003 21 Astraatmaja, Fuad, Ginting, Loraas: Case study 3. 22 Tempointeraktif 28.8.2006. 16 forest guardians do not make difference between professional illegal log traders and villagers that live in the area. Most often the big actors are inside Perhutani and the actors in the companies or related to them. In the internal organization before 2005 the management system allowed the head of KPH (administrator – adjun) to lead the forest management and business. Many timber companies are in a need of teak trees and paid “fees” to the administrator in order to get teak. The demand for teak has been bigger than the supply. Thus, many administrators have had the systems that company that offers more money will get the timber. The high demand and corruptive practices inside Perhutani have made it attractive to cut and sell teak illegally. Since 2005 the business management has been separated in a hope that administrators would not take part in corruption and mediating illegal logs. According to Perhutani, already in 2006 and 2007 the situation has got better. 23 However, one has to note also that teak plantations are getting empty of trees and thus there is not much left to log illegally. “For instance, I dont want to say the name, but ex-administratorKPH Ngawi (East Java) told me that in one yearearlier he could get 1 billion rupiah from teak trade. Despite the fact that Ngawi is not the area of good quality teak area, it is not status A, and the area is not very big. Imagine the benefit the administrator could get from the area with statu A. This administrator got his fees from the enterpreuners. He did not have to go to look for illegal logs, because the enterpreneurs paid so well.”24 The actors mentioned being involved in the illegal loggings are: Private company actors, district state officials and politicians, army members and village heads.25 Enforcement of law is not working and Perhutani has been fragmented internally. Biodiversity During the Dutch period the distance between the teak trees was 1x3 meters but since 1970s teak trees have been planted with the distance of 3x3 meters. The 3x3 meters is more beneficial to the local people in the sense that they may plant in between the tree rows their own cash crops like cassava, beans and corn as long as the teak trees are not too high to shadow the crops. The problem is that teak trees are ready to be cut in 60-80 years, which means that during a long period villagers are not able to have multiple cropping (tumpang sari) in the area and they are not allowed to plant any other tree species on the teak plantation area. This situation often leads people to cut trees without permission from the forest. In the people’s forest (hutan rakyat - covers about 590 000 hectares of land in Java) villagers plant multiple tree species and crops in the same area in order to always have some harvests and income. In this way they also guard the biodiversity and water system. In the plantations all the teak trees are cut at the same time, besides harvesting. Thus, the ecological system (vegetation, and animals, water system) will be disturbed. 22. Anonymous staff of Perhutani, Jakarta.Interview by Saleh Abdullah. 1.5.2007.1.5.2007. The news about illegal logging going on as before in Randublatung in 2006 show that things are not yet in condition. 24 Anonymous staff of Perhutani, Jakarta.Interview by Saleh Abdullah. 1.5.2007.1.5.2007. 25 Anonymous staff of Perhutani, Jakarta.Interview by Saleh Abdullah. 1.5.2007. 1.5.2007 Photo: Arupa: beans and corn in between teak rows. Livelihood, and land tenure In most of the production forest areas where different tree specie plantations are developed Perhum Perhutani nowadays tries to implement the PHBM (Pengelolaan Hutan bersama masyarakat – forest management together with people) system. It means that Perum Perhutani gives a permission for the villagers to process plots of land and plant there crops (most often rice, maize, cassava, beans) while planting the teak seedlings and guarding that the seedlings don’t die. It is then in the responsibility of the farmers to buy and plant new seedlings if the seedlings die. Farmers are not given salary since they may plant their own crops there. Villagers also often bring fertilizers (goat extracts or else) in order to make the crops grow. However, while villagers may have agricultural practices in these areas, the system benefits Perum Perhutani which does not have to pay labor for turning the land, planting seedlings and guarding seedlings and giving fertilizers. Besides after some years, peasants have to give up agricultural practices since the trees grow too big. However, in some new models of PHBM villagers may also plant fruit trees or fast growing sengon or other species and share the harvest with Perum Perhutani. In general Perum Perhutani does not tell to planting labor and lower staff their salary. Actually there is no central policy for that matter. Sometimes planting of teak seedlings is paid per seedling (1 seedling 100 rupiah), however the side work (turning land, giving fertilizers, guarding the seedlings) is not counted and paid. Sometimes Perhutani pays 100 000rp per hectare that is worked by four people. AruPa has counted that the work takes 2 weeks, meaning that each laborer gets 25 000rp/ 2 weeks. The normal daily labor salary in the village is about 20 000/ 12 hours. Javanese People’s Forest Forum (FKKM) has counted that people invest about 50-65 present to the land of teakl plantation with their work (planting, guarding, turning land, giving fertilizers), but have got almost nothing out of their investment. Today Perum Perhutani further develops its social forestry system PHBM (Pengelolaan Hutan bersama Masyarakat - Social Forestry program) in the hope that the teak and other wood species would be certified. According to Perum Perhutani, the program covers already 80 percent of the total amount of forest villages in Java.26 Here village people are asked to participate in developing the forest model, and the process of creating and guarding the forests. However, the system varies from village to village. Every village forest organization negotiates its own agreement with Perum Perhutani with rights and responsibilities. The most important aspect is share from the “harvest” that is when teak trees are cut. The sharing may vary from 15 to 25 percent to the villagers and rest to the Company. Most often the villagers get 15 percent.27 Often villagers have the responsibility to guard the forest. If teak trees are cut before the time and illegally, the share of the forest people will be reduced. Thus day and night, seven days a week that have to keep their eyes open.28 Villagers get user rights to land normally defined in terms of harvesting and cutting period. However, it does not change the position of the villagers in relation to property right conflict. Conclusions Perum Perhutani plans to have other forest management systems besides teak plantation. For instance, it has high hope for pine trees and resin in the future. However, for many villagers pine trees are even more problematic than teak plantations, since the needle leaves that make it difficult to have multiple cropping on same land, and also because pine trees are said to impact the water balance. Land tenure conflict will continue as long as Perum Perhutani do not admit that forest villagers living nearby the state forest area are in urgent need of land and multiple harvests, and that monoculture forests are always a problem for the villagers. State forest areas are constructed above legitimation by the Dutch colonial power in the lands that were considered “empty” but which may have offered temporary income to the people. Perum Perhutani with its legal mandate manages the land under this premise. The property right conflict is historically inherent in the relation between Perum Perhutani and forest peasants in Java. Perum Perhutani is said to have new uncorrupted director, Transtoto, who is trying to clean the management. However, already decades the administrators in the leadership of KPH units have worked almost independently or in the corrupted system whereby state and village officials, politicians and private company people have all been somewhat corrupting each other. 26 Director of Perhutani, power point presentation, May 2007. However, there is also data indicating that 63 percent of the forest villages take part in the program. We also don’t know how high is the participation at the village level. There are problems such as that many village heads want to become the head of the program and forest institution at the village level, or vice versa head of the program in the village is chosen as a village head. 27 Anonymous staff of Perhutani, Jakarta.Interview by Saleh Abdullah. 1.5.2007 28 Saleh Abdullah interview with Rama Astraatmaja, AruPa, May 2007. Appendix 1 Date Place event source D shooting SP 5/3/98 1 shooting SP 24/7/98 2 1 01-Mar-98 2 28-Jun-98 North Banyuwangi Randublatung 3 27-Okt-98 Purwodadi shooting SP 29/10/98 4 5 18-Jul-99 01-Jan-00 Semarang Probolinggo shooting shooting 1 1 6 01-Jul-00 Semarang Shooting SP SU 30/5/01 Bernas 01/01/00 Cepu Shooting IO 6/11/00 1 Cepu West Banyumas Nganjuk Saradan/Nganjuk Shooting Shooting Shooting Shooting ARuPA KP 6/4/01 KP 27/4/01 RP 19/7/01 1 Majalengka Shooting PR 8/11/01 Banten Banyumas Timur Blora Cepu Rembang Shooting Shooting Shooting Torturing Shooting KT 19/1/02 KR 29/01/02 KR JP 1 ARuPA Total 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 05-Nop00 01-Des-00 31-Mar-01 18-Apr-01 18-Jun-01 01-Nop01 18-Jan-02 26-Jan-02 29-Apr-02 14-Okt-02 01-Apr-03 B w 1 5 3 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 17 2 D:Died, W:wounded, B:building broken Source: Newspaper clipping digital (1997-2002) and report by ARuPA 1998-2003. AruPa. SP= Suara Pembaruan, KP = Kompas, RP = Republika, KR = Kedaulatan Rakyat,PR = Pikiran Rakyat SU = Surabaya Post, KT = Koran Tempo, IO = Indonesian Observer JP = Jawa Pos Appendix 2 Victims No Date KPH Event wounded Died 1 1.March.98 North Banyuwangi Shooting 1 2 6.June 98 WestBanyumas Shooting 3 22. June.98 Lumajang Shooting 4 28.June98 Randublatung Shooting 1 5 27-Oct-98 Purwodadi Shooting 5 6 4.June99 North Banyuwangi Shooting 1 7 27.June.99 Kendal Shooting 2 8 27.June 99 Kebonharjo Shooting 2 9 18.July99 Semarang Shooting 3 1 1 2 1 10 24-Agu-99 Blitar Shooting 11 1.Janyuary 00 Probolinggo Shooting 12 1.July00 Semarang Shooting 13 5-November-00 Cepu Shooting 1 14 1-Dec-00 Cepu Shooting 1 15 5-Dec-00 Jember Shooting 2 16 ######### Kebonharjo Shooting 1 17 ######### West Banyumas Shooting 3 18 18.April 01 Nganjuk Shooting 1 19 29. April.01 Kendal Torturing 1 20 18 June.01 Saradan/Nganjuk Shooting 1 21 5-Agu-01 Balapulang Shooting 22 24-Agu-01 Indramayu Shooting 4 23 1-Nop-01 Majalengka Shooting 1 24 ######### Banyumas Timur Torturing 1 25 29.April02 Blora Shooting 1 26 2002 Randublatung Shooting 2 27 14 Oct02 Cepu Torturing 28 25 Dec02 Purwodadi Shooting 1 29 2March.03 Saradan Shooting 1 30 3.March.03 Pasuruan Shooting 1 31 1.April03 Rembang Shooting 1 32 28.July.03 Kendal Shooting 4 33 26Sept03 Balapulang shooting 1 34 8 Oct.03 Banyuwangi Selatan Shooting 35 16-Dec-03 Randublatung Shooting 1 1 36 15-July-04 Blora Shooting 37 15-Sept-04 Mantingan Shooting 1 38 2-Dec-04 Kendal Shooting 1 39 16-Apr-05 Gundih Shooting 1 40 13-May-05 Rembang Shooting 2 41 13-May-05 Rembang Torturing 1 42 30-May-06 Semarang Shooting 1 43 13-Jun-06 Randublatung Torturing 1 Total Sources: AruPa: newspaper clippings and field findings 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 1 47 24