Ethan Frome - Universitatea din Craiova

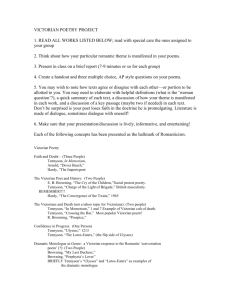

advertisement