Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and Terrorism

advertisement

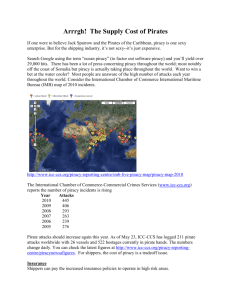

Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection PIRACY, ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS AND THE TERRORISM CONNECTION "Piracy is entering a new phase; recent attacks have been conducted with almost military precision. The perpetrators are well-trained, have well laid out plans." Statement by Singapore's Deputy Prime Minister Tony Tan UNITED KINGDOM: Piracy soars as violence against seafarers intensifies 24-07-2003 10:36:00 GMT Piracy (including Armed Robbery Against Ships) against the world's shipping surged in the first half of… (2004), with a record 234 attacks reported and violence against seafarers escalating, the ICC International Maritime Bureau said today. Again, waters off Indonesia were the most dangerous.” The IMB Report, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships, showed a rising toll of dead and injured seamen as the number of incidents in which firearms were used rose. A total of 16 seafarers were killed in piratical attacks during the period, 20 were reported missing, and 52 were injured. Numbers taken hostage more than doubled to 193. IMB Director Captain Pottengal Mukundan said: 'Levels of violence have increased significantly.' He instanced as typical incidents the fatal shooting in the head of a ship's officer on board a tanker off Santos, and the abduction of crew for ransom off Nigeria where their vessel was run aground. Pirate fired a hail of bullets from automatic weapons at a chemical tanker off Indonesia in an attempt to force it to stop. A ship's engineer was hit and was rushed to hospital for emergency treatment. The figures were the worst for a six months period since the IMB, a specialized division of the International Chamber of Commerce, started compiling global piracy statistics in 1991. The number of attacks rose 37% compared with 171 during the corresponding period in 2002, when six crew members were killed. IMB officials said the final outcome was likely to be even higher because of a time lag in reporting incidents. 21-1 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies The highest number of attacks was recorded off Indonesia, which accounted for more than one quarter of the world total with 64 incidents. These included 43 ships boarded, four hijacked and attempted attacks on a further 17 ships. The IMB said there are no signs of a reduction in attacks, and no improvement could be expected until Indonesia took serious steps to tackle piracy in its waters. Among other piracy-prone areas, attacks doubled off Bangladesh where the number of attacks doubled to 23. Nigeria and India, with 18 attacks each, occupy third place in the table. Captain Mukundan said the information the IMB was able to provide law enforcement agencies was now more accurate and up-to-date than ever before. 'Law enforcement agencies can thus increase their presence in high risk area to prevent the loss of life and injury to seamen that we have seen in the first six months of this year,' added Captain Mukundan. The report identifies 26 ports and anchorages that are the most prone to attacks. Chittagong, Lagos, Cochin, Chennai, Dakar and Rio Haina headed the list. The report highlights the following piracy prone areas; S E Asia and the Indian Sub Continent - Bangladesh: Chittagong and Mongla at berth and anchorage. - India: Chennai, Cochin - Indonesia: Adang Bay, Balikpapan, Dumai, Gaspar (Gelasa) Straits, Kuala Langsa, Lawi Lawi, Pulau Laut, Samarinda, Tanjong Priok (Jakarta). Areas around Anambas and Bintan Islands - increasing number of serious and brutal incidents have been reported within 30 km radius of Lat 01 N - Long 105 E in June 2003. - Malaysia: Pulau Pangkor 21-2 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection - Philippines: Manila, Zamboanga - Vietnam: Haipong, Vung Tau Africa and Red Sea - Africa: Abidjan, Bonny River, Dakar, Dar Es Salaam, Lagos, Luanda, Nana Creek, Tema, Warri. - Gulf of Aden - Somali waters: Eastern and Northeastern coasts are high-risk areas for hijackings. South and Central America and the Caribbean waters - Colombia: Barranquilia, Buena Ventura, Cartagena - Cuba: Havana - Dominican Republic: Rio Haina - Ecuador: Guayaquil - Guyana: Georgetown - Jamaica: Kingston - Peru: Callao The Report also draws attention to IMB's recent initiative to take the fight against piracy onto the Internet with weekly updates of attacks and warnings. The service, which has been well received in the shipping world, is compiled from daily status bulletins to ships at sea broadcast via satellite from the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre in Kuala Lumpur. Posting the information on the Internet means shipowners and land-based authorities are able to access the updates. The address for the weekly report is www.icc-ccs.org 21-3 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies The work of the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre is funded by 21 organizations, mostly P&I Clubs, ship owners and insurers. The Centre is now recognized throughout the maritime industry for its valuable contribution in quantifying the problem of world piracy and providing assistance, free of charge to ships that have been attacked. The attacks reported by the IMB account for 95% of the attacks officially released by the International Maritime Organization. The IMB's Annual Report on piracy seeks not only to list the facts, but also to analyse developments in piracy and to identify piracy-prone areas so that the crew can take preventive action. Copies of the report, priced £18 inclusive of postage and further information can be obtained from: ICC- International Maritime Bureau Maritime House 1 Linton Road, Barking Essex IG11 8HG, United Kingdom Tel. ++ 44 20 8591 3000, Fax. ++ 44 20 8594 2833, E-mail: imb@icc-ccs.org.uk Instructor note regarding title slide: In October 1999, the cargo ship Alondra Rainbow left the Indonesian port of Kuala Tanjung bound for the port of Mike in Japan. It never arrived. Instead, the ship was boarded by armed pirates who put the 17 crew members in an inflatable liferaft and set them adrift. Although they were passed by six ships, it was not until eleven days later that they were finally rescued by fishermen. In September 1998, the Panama-registered Tenyu also disappeared in the Straits of Malacca while en route from Indonesia for the Republic of Korea with a cargo of aluminium ingots. It later reappeared, but with a different name and crew. It is almost certain that the original crew of 17 were murdered. In November 1998, the bulk carrier MV Cheung Son was attacked by pirates in the South China Sea. Its crew of 23 were shot and their bodies thrown overboard, weighted down to make them sink. Not all did so. Fishermen off the coast of China later found six bodies in their nets, still bound and gagged. I. BACKGROUND 21-4 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection A. Gone are the days when the pirates had eye patches, swords, and were the masters of fast cutters; now it's sun glasses, cellular phones and high-speed boats. Today's ships, with their high-value cargos and small crews to man the ships that carry them, are highly vulnerable to criminal predators in high-speed boats, armed with modern assault weapons, and operating in sea lanes that international carriers must traverse. Pirates are thus able to make surprise attacks on unarmed merchantmen and get away with money and other valuable articles. The end of both colonial controls and latter the cold war has reduced naval presence and capability in regions where piracy has historically flourished. B. Pirates historically have posed a serious threat to maritime commerce; a threat significant enough that it forced nations to join together to combat what might have been the first recognized international crime. Pirate ships were almost always too heavily armed for individual merchant ships to defend against, but were usually easily outgunned by most warships. Individually and working together, the world’s navies essentially drove pirates from the seven seas during the 19th Century. Unrecognized by the general population, pirates have returned to once again prey on maritime commerce. Modern day pirates pose the same threat of danger, loss, and expense as those of yesteryear; however, automatic weapons, mortars and rocket-propelled grenades have replaced cutlasses. C. Today's piracy is more than a nuisance to commercial shipping. It affects maritime traffic in vital shipping lanes, particularly in Southeast Asia. Attacks on oil supertankers hold the potential to ignite environmental disasters. Attacks by pirate craft may invite military reprisals, and there is a continuing problem off the coast of China with what amounts to state-sponsored piracy by some official Chinese craft. D. The concentration of piracy incidents continues to be located in areas with little or no maritime law enforcement, political and economic stability, and a high volume of commercial activity. Incidents of piracy tend to occur in four regional areas: Southeast Asia, Africa, South America, and Central America. Furthermore, most incidents of maritime crime occur in coastal waters with nearly 80 percent of all reported piracy incidents occurring in territorial or internal waters. Within the past 15 years, these crimes in the territorial sea and internal waters have come to be known as “Armed Robbery Against Ships.” In the press and governmental statements, especially, the term piracy is frequently used to encompass both traditional piracy on the high seas and “Armed Robbery Against Ships.” The statistical reports issued by the International Maritime Organization and the IMB contain both piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships offenses. 21-5 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies E. The total damage caused by piracy-due to losses of ships and cargo and to rising insurance costs-now amounts to $16 billion per year. It is widely accepted among the government and non-government organizations that track piracy worldwide (including the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), U.K. Defense Intelligence Service (DIS), Australian Defence Intelligence Organization (DIO) and the International Maritime Bureau (IMB)), that the annual number of piracy cases is seriously undercounted. DIS estimates the actual number of piracy cases could be 2,000 percent higher on an annual basis while DIO estimates the underreporting to be 20 to 70 percent.44 Since the establishment of the IMB's Regional Piracy Center in Malaysia in 1992 and its subsequent efforts to publicize the piracy problem, there has been increased reporting on major incidents, but incidents involving fishermen and recreational boaters are still heavily undercounted. Also, the average loss from a piracy incident does not cross the monetary threshold for insurance action, further contributing to underreporting. Most incidents will continue to go unreported except in cases where there is serious loss of property and life or damage to a foreign interest. Note concerning powerpoint slide 3: Photo is of the French flag tanker T/V Limburg attacked by an explosive laden terrorist suicide boat while underway off Yemen in October 2002. Note concerning the powerpoint slides: Slides 5, 6 and 7 represent an overview of piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships around the world in 2001 and 2004. You will note that the trend line is generally up in most locations. The data and slides were produced by the International Marine Bureau (IMB). II. PIRACY DEFINED A. In 1924, the international law definition of piracy remained unsettled and the international legal community moved to standardize the jurisdictional bases applicable to piracy. The League of Nations prepared and delivered "The Report on Piracy" to its member governments in the hope that a treaty relating to piracy would result. Unfortunately, the report was ignored because it was felt that 'piracy' under that name was no longer a pressing issue in the international community. B. In 1932, Harvard Law School in the United States devised the next effort to codify an international law of piracy. The nineteen-article draft convention was never formally adopted, but it did provide the foundation for the United Nations International Law Commission's (ILC) work on the subject. The ILC's text then 21-6 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection became the basis for defining piracy in the 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas (entered into force 30 September 1962) and in the parallel provisions of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (entered into force 16 November 1994). C. Article 100 of UNCLOS obligates the parties to "co-operate to the fullest possible extent in the repression of piracy on the high seas or in any other place outside the jurisdiction of any State. D. Article 101 of the UNCLOS defines piracy as follows: Any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed: E. 1. On the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft; 2. Against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State; 3. Any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate-ship or aircraft; 4. Any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (1) or sub-paragraph (2) of this article. Additionally, Article 105 of UNCLOS provides that: On the high seas, or in any other place outside the jurisdiction of any State, every State may seize a pirate ship or aircraft, or a ship taken by piracy and under the control of pirates, and arrest the persons and seize the property on board. The courts of the State which carried out the seizure may decide upon the penalties to be imposed, and may also determine the action to be taken with regard to the ships, aircraft or property, subject to the rights of third parties acting in good faith. In international law piracy is a crime that can be committed only on or over international waters (including the high seas, exclusive economic zone, and the contiguous zone), in international airspace, and in other places beyond the territorial jurisdiction of any nation. The same acts committed in the internal waters, territorial sea, archipelagic waters, or national airspace of a nation do not constitute piracy in international law but are, instead, crimes within the jurisdiction and sovereignty of the littoral nation. 21-7 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies Article I, section 8 of the United States Constitution empowers Congress to define and punish acts of piracy. While early federal court decisions characterized piracy as "robbery and murder on the high seas" and "depredation of the seas," later courts have focused on the utility of punishing piracy in order to facilitate the right of all countries to "navigate [freely] on the high seas." Current legislation requires stringent punishment of a convicted pirate. The United States, however, defers its definition of piracy to international law. III. ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS A. Many maritime crimes that historically had been considered piracy were committed between 3 and 12 miles off the coast of a coastal state. One of the unintended consequences of the extension of the territorial sea from 3 nautical miles to 12 nautical miles by UNCLOS was that pre-UNCLOS acts of piracy committed within this area were no longer considered piracy under international law. Given the economic, environmental and human significance of maritime crimes committed in the territorial seas as well as internal waters of coastal states, a new term for maritime crime committed in these areas has been created. This crime is called “Armed Robbery Against Ships.” B. Armed Robbery Against Ships is a term used to describe attacks upon commercial vessels in ports and territorial waters. Such attacks are, according to international law, not true acts of piracy but rather armed robberies. They are criminal assaults on vessels and vessel crews, just as may occur to truck drivers within a port area. Such attacks pose a serious threat to trade. The methods of these attacks have varied from direct force using heavy weapons to subterfuge in which the criminals have identified themselves on VHF radio as the national coast guard. . C. Armed robbery against ships. is defined in the International Maritime Organization’s Code of Practice for the Investigation of the Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships (resolution A.922(22), Annex, paragraph 2.2), as follows: Armed robbery against ships means any unlawful act of violence or detention or any act of depredation, or threat thereof, other than an act of piracy, directed against a ship or against persons or property on board such ship, within a State’s jurisdiction over such offences.. D. This definition for Armed Robbery Against Ships is broad enough to include taking of hostages from the ship’s crew or passengers and holding them for ransom; a crime sometimes committed by terrorists to raise funds for terrorist causes or extort some governmental action. 21-8 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection E. IMB publishes highly respected and widely cited monthly and annual statistics regarding piracy and armed robbery against ships. For statistical purposes, the IMB defines piracy and armed robbery against ships as An act of boarding or attempting to board any ship with the apparent intent to commit theft or any other crime and with the apparent intent or capability to use force in the furtherance of that act. This definition thus covers actual or attempted attacks whether the ship is berthed, at anchor or at sea. Petty thefts are excluded, unless the thieves are armed. IV. HISTORICAL EFFORTS TO COMBAT PIRACY A. Pirates have existed throughout history. Among the earliest ancient Greek records of piracy is the story of Sennacherib, an Assyrian king who fought a great battle against the Chaldean Sea Raiders in the Northern Persian Gulf in 694BC. The Romans also had their problems with pirates, and in 75BC a pirate gang made the mistake of kidnapping and ransoming the young Julius Ceasar. The future Roman Emperor went on to track down the gang and to crucify all the pirates. B. The South China Sea has historically been a favored haunt of pirates. By AD400 the problem had become so acute that the Chinese and Japanese authorities collaborated in a purge of pirates. As trade with Europe developed, the Asian pirates targeted western ships. In 1849 the British Royal Navy inflicted a famous defeat against the Chinese pirate leader Shap'n'gtzai in the Haiphong Delta. The power of the South China pirates was largely broken by the 1860's, although shipping continued to give Bias Bay, just fifty miles east of Hong Kong, a wide berth, as it was known as a pirate base until as late as the 1930's. C. What is frequently thought of as the Golden Age of Piracy was the result of the European powers’ colonization of the America. Initially, Spain was the principal American colonial power. In the 16th and 17th centuries, pirates from a number of nations preyed on Spanish galleons carrying the treasures of the New World back to Spain. After 1588 and the English defeat of the Spanish Armada, France and England began to colonize North America and the Caribbean. Pirates spread outward from the Caribbean as more of the Americas were colonized. The spread of pirates was encouraged by the two wars fought between England and France: King William’s War (1689 – 1697) and Queen Anne’s War (1702 – 1713). During both wars, England and France commissioned numerous privateers to carry out their naval wars in North America. Many of the privateers failed to properly follow their commissions and some pirates forged commissions to give themselves a veneer of legality. Once the conflicts were over, moreover, many 21-9 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies privateers were reluctant to return to fishing and merchant shipping and took up piracy. Some of the famous pirates of these days were Blackbeard (Edward Teach), Black Bellamy, and the most successful pirate, Henry Morgan. Morgan was a privateer hired to defend Jamaica who switched to piracy including capturing Panama. Morgan was brought to England and tried for piracy, but he was acquitted. Later he was knighted and became Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. There were even female pirates such as Anne Bonny and Mary Read. D. England, France and their colonies all tried to strike back against the pirates, but the same lack of a strong naval presence that encouraged the use of privateers made combating the pirates difficult. An example of the frustration of combating pirates is the efforts of New York’s governor Bellmont. In 1695, he hired and outfitted Captain William Kidd as a privateer to attack pirates, but once Captain Kidd set sail, he too reportedly acted as a pirate. He was hung in Boston in 1702 when he was unable to produce the proper documentation to show that he was acting within the scope of his commission. E. Through the combined efforts of the major seapowers and key coastal states, pirate activities almost ceased in the 19th through the mid-20th century for a number of reasons, principally: 1. The increase in size of merchant vessels, 2. Naval patrolling of most ocean highways, 3. Regular administration of most islands and land areas in the world, and 4. General international recognition of piracy as an international offense. As noted above, today, piracy is a growing problem in the 21st Centure. The director of the IMB observed that: "Pirates are also gaining confidence because they so often get away with it. When Blackbeard terrorized the North Carolina coast of the U.S. in the early 1700s, navies were powerful and justice summary. Blackbeard's career ended when his head was sliced off by a Royal Naval broadsword. These days, concerns over sovereignty and territorial waters foster caution. There is no law enforcement at sea by anyone--today's navies are reluctant to intervene in the act of piracy." V. MODERN DAY PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS For purposes of the following discussion the term “pirates” refers to persons committing both piracy as defined in international law and Armed Robbery Against Ships. A. Modern-day pirates can be divided into three kinds: 21-10 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection 1. "Smaller" pirates who simply rob the crew and then depart. This usually occurs when the victim vessel is at anchor or at port. a. Smaller pirates are usually only interested in the safe of the ship where considerable amounts of money are often kept and the possessions of the crew. The crews are most often left unharmed, if the crime is committed at sea, the ships are usually set adrift. b. When the pirates are finished looting a ship they can usually escape fairly easily because they usually leave the crew imprisoned or, if underway they may force them off the ship before they leave. At sea, the pirates can also choose which nation's coastal waters they will escape to. Some of the people in the coastal villages and local towns of Indonesia, Malaysia or Singapore are even sympathetic towards the arrival of pirates. In the Far East, where many of these piracy attacks occur, pirates have several harbors to hide in and operate from, where the locals will protect them. B. 2. The second category of pirates are those who rob the crew and steal the cargo on board. 3. The third type of pirates take over the vessel, re-flag it, and then run a "phantom ship" which in turn, steals the cargo of anyone foolish enough to consign such goods to it. The second and third types of pirates tend to be much more organized, "professional" pirates. They are often linked to other criminal organization, on land which assist them to carry out the sale of the stolen goods and cargo, and assist in the forging of cargo documentation. The following is an example of the activities these pirates undertake: 1. The pirates look for a commodity seller or shipping agent with a letter of credit that has almost expired (this happens regularly since the demand for shipping space exceeds that which is available). 2. The pirates then offer the services of "their" ship. (This is the ship that is stolen, re-painted, re-named, and re-registered). 3. A temporary registration certificate is then acquired through a registration office at a consulate office. To get such a certificate a bribe combined with verbal information or some false and/or forged documents are necessary. This certificate provides the ship with an official (new) identity. 4. The ship is loaded and the shipper receives his bill of lading. 21-11 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies 5. C. The pirates then sail to a different port than the one named as the destination on the bill of lading. There they unload the cargo to a partner in crime or an unsuspecting buyer and change the temporary registration certificate once again.3 The third type of pirates described involves sophisticated organizations of pirates who are able to steal at least $200 million a year worth of cargo. Many of the ships are then flagged in either third world or economically underdeveloped countries (like Honduras and Panama), and usually take cargo that is easily disposed of but not easily traceable, such as timber, metals, and minerals. The significance of the third type lies in the sophistication of these maritime thieves. As indicated by the measures these pirates take, outlined above, they are professional thieves. All three types of piracy are of concern. But, where the cargo and/or ship is the target, the human cost is of greatest concern since lives are at stake. It is not unusual in these cases for the crew of the hijacked ship to be marooned or even thrown overboard by the pirates. The International Maritime Bureau reported in its annual piracy report for 2004 that pirates preying on shipping were more violent than ever in 2004 and murdered a total of 30 crew members, compared with 21 in 2003,. D. As noted earlier, during the modern era, the largest number of acts of piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships occur in Southeast Asia. Pirates also constitute a significant threat in the Indian Ocean, East Africa, and South America. A list of piracy prone and warning areas identified by the IMB: 1. S E Asia and the Indian Sub Continent a. Bangladesh: Chittagong at berth and anchorage. b. India: Chennai , Kandla 2. Indonesia: Anambas/Natuna Island, Balikpapan, Belawan, Dumai, Gaspar/Bar/Leplia Str, Jakarta (Tg.Priok), Pulau Laut, Vicinity of Bintan Island 3. Malacca straits: The Coast near Aceh is particularly risky for hijackings. 4. Singapore Straits 5. Africa and Red Sea a. Gulf of Aden / Southern Red Sea 21-12 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection 6. E. b. Somalian waters: Eastern and northeastern coasts have been highrisk areas for hijackings. Ships not making scheduled calls to ports in these areas should stay away from the coast. c. West Africa: Abidjan , Conakry , Dakar , Douala , Freetown, Lagos , Tema, Warri South and Central America and the Caribbean waters a. Brazil – Rio Grande b. Haiti – Port au Prince c. Dominican republic - Rio Haina d. Jamaica - Kingston e. Peru – Callao The following piracy incidents were reported by IMB for one week in June 2005: 19.06.2005 at 2030 LT in position: 02:03N - 119:20E, Indonesia. Pirates in a speedboat attempted to board a bulk carrier underway from poop deck. Master took evasive manoeuvres, raised alarm and directed search lights at boat and boarding was averted. 17.06.2005 at 0300 LT, in position 03:12S - 116:20E, Tanjung Pemancingan anchorage, Indonesia. Ten robbers armed with long knives boarded a bulk carrier at forecastle. They tied up duty watchman and threatened another watchman. Robbers broke open locker and stole ship's stores. 17.06.2005 at 0240 LT, 6 nm from fairway buoy, Lagos anchorage, Nigeria. Six robbers armed with guns and knives in a speedboat came alongside a bulk carrier. Four robbers boarded, held duty A/B at gunpoint and stole ship's stores. A/B managed to raise alarm and crew mustered. Robbers escaped with ship's stores into a waiting speedboat. No injuries to crew. Master reported to port authorities and heaved up anchor proceeded to sea for drifting. 16.06.2005 at 0115 LT at berth no.4, Jawahar deep terminal, Mumbai, India. Two robbers boarded a tanker discharging cargo. They tried to steal ship's stores from poop deck but duty A/B noticed them and raised alarm. Robbers escaped empty 21-13 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies handed in an orange coloured boat. Port authorities informed and they came on board for investigation 15.06.2005 at 1800 UTC LT in position 01:59N - 104:45E, South China Sea. Three unlit crafts approached a general cargo ship underway and came within 1 cable at port bow. D/O raised alarm, crew mustered, directed searchlights, switched on deck lights and activated fire hoses. Crafts then changed course and attempted to board at stern. Finally they moved away. 15.06.2005 at 0315 LT at Basra oil terminal anchorage 'B', Iraq. Three robbers armed with machine guns and long knives boarded a tanker via forecastle. Alert A/B raised alarm. Robbers stole ship’s property and fled in their speed boat. No casualties. This is the second incident in this location since 31.05.2005. 14.06.2005 at 0430 LT at Douala port, Cameroon. Four armed robbers boarded a general cargo ship at berth. They assaulted duty A/B and forced him to open Bosun store. A cadet on rounds came to forecastle and he along with the A/B were held as hostages. Robbers stole ship's stores and escaped leaving the two hostages in Bosun store. Master reported incident to port control. 14.6.2005 at 0400 LT off Langkawi Island, Malacca straits. Ten pirates armed with weapons in a speedboat hijacked a tanker underway. One crew managed to escape in the boat used by pirates. He landed ashore and contacted marine police at Langkawi Island. Police despatched a patrol boat and located the hijacked tanker off Pulau Lebar. Subsequently, pirates surrendered and they were taken to Langkawi for investigations. 12.06.2005 at 1100 LT at Warri region, Nigeria. A group of armed persons boarded an offshore processing tanker. They took hostage all 45 crewmembers. After negotiations boarders departed on 15.06.2005 at 0945 LT. No injuries to crew. VI. PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY OF SHIPS: THE TERRORISM CONNECTION 21-14 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection Jolly Roger flies again: Piracy and terrorism in the Strait of Malacca January 28, 2004--Could pirates and terrorists team up to stage a dramatic attack in one of the world's most strategic choke points? According to several maritime trade associations and international security organizations, Islamic terrorists in Southeast Asia could be contracting or teaming up with pirates to attempt a large-scale attack, either on a ship or port in the Strait of Malacca. By Tad Trueblood Johnny Depp was dashing and cute in the recent hit movie “Pirates of the Caribbean”, with his tri-cornered hat, gold tooth and mischievous grin. Real pirates, however, weren’t ever very dashing, and their counterparts today aren’t cute. The jaunty hats went out of style generations ago, but murder, rape and brutality are still in. What’s new is the merging threats of piracy and big-league terrorism. The Strait of Malacca in Southeast Asia runs for 620 miles between the landmasses of the Malay peninsula and the island of Sumatra. Just a mile and a half wide at the narrowest point, hundreds of vessels pass through this vital chokepoint every day--over 50,000 a year. A huge chunk of the world’s cargo capacity moves through Malacca, including half the world’s oil and two thirds of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) shipments. Naturally enough, the strait is also one of the primary hunting grounds for modern-day pirates, who typically use small power craft to forcibly board large commercial freighters or tankers. Half of the world’s pirate attacks happen in or near the Strait of Malacca. The loot isn’t golden doubloons, but cash and valuables from the crew, high-value cargo, and readily marketable fuels--which the pirates pump into their own tanks to sell later. Violence often accompanies the boardings, in the form of beatings, rapes, kidnapping and killings. Incidents of piracy were up worldwide in 2003, driving up international shipping costs and insurance rates which in turn hurts businesses and consumers everywhere. Now there’s a new dimension to the problem. According to several maritime trade associations and international security organizations, Islamic terrorists in the region could be contracting or teaming up with Southeast Asian pirates to attempt a large-scale attack, either on a ship or port. There are several militant Islamic groups, allied or associated with al-Qaida, that operate nearby in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. These groups 21-15 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies often have ties to, or connections with the pirates and recent incidents lead shipping experts to suspect that a maritime attack plan is in the works. Several merchant vessels in the area have been hijacked temporarily--possibly as some kind of training exercise. A chemical tanker was boarded recently off the Indonesian island of Sumatra and the hijackers piloted it for over an hour before leaving. In the Philippines, the Abu Sayyaf Islamic radicals kidnapped a professional maritime engineer and forced him to teach them diving techniques. Captured al-Qaida videotapes from Afghanistan have shown surveillance of Malaysian police patrol boats. There are also tugboats that have gone missing, prompting fears of some kind of suicide run in one of area’s crowded ports. For several years, al-Qaida terrorists have been investing time and energy in building up their expertise in maritime operations--and have carried some out successfully. In 2000 bombing of the USS Cole killed 17 U.S. sailors while their ship was at anchor in Yemen. In October of 2002, the French oil tanker Limburg was bombed in the Gulf of Aden, splitting the vessel’s hull. Also in 2002, a daring al-Qaida plan to attack U.S. and NATO warships in the Strait of Gibraltar was fortunately uncovered and disrupted. al-Qaida’s chief of naval operations and mastermind of the Cole attack, Mohammed Abda Al-Nasheri, is now in custody but plans he began may still be in motion. Even with the so-called “Prince of the Sea” behind bars, there is concern of another devastating attack on a hub of world trade-not from the air, but from the sea. An official with the International Tanker Operators Association says if terrorists managed to crash a tanker full of liquified natural gas into the docks in Singapore, the results would be "more devastating than any bomb. . . too horrible to think about." The scourges of piracy and terrorism are increasingly intertwined: piracy on the high seas is becoming a key tactic of terrorist groups. Unlike the pirates of old, whose sole objective was quick commercial gain, many of today's pirates are maritime terrorists with an ideological bent and a broad political agenda. This nexus of piracy and terrorism is especially dangerous for energy markets: most of the world's oil and gas is shipped through the world's most piracyinfested waters. A. Terrorism is a complicated concept. A working definition of maritime terrorism is 21-16 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection that of political piracy: "... any illegal act directed against ships, their passengers, cargo or crew, or against sea ports with the intent of directly or indirectly influencing a government or group of individuals for political or ideological purposes." B. Terrorism is distinct from piracy in a straightforward manner. Piracy is a crime motivated by greed, and thus predicated on immediate financial gain. Terrorism is motivated by political goals beyond the immediate act of attacking or hijacking a maritime target. C. Piracy and terrorism overlap in several ways, particularly in the tactics of ship seizures and hijackings. And some of the circumstances that allow piracy and terrorism to flourish are similar, such as poverty, political instability, permeable international boundaries and ineffective enforcement. D. If a single tanker were attacked on the high seas, the impact on the energy market would be marginal. But geography forces the tankers to pass through strategic chokepoints, many of which are located in areas where terrorists with maritime capabilities are active. These channels, major points of vulnerability for the world economy, are so narrow at points that a single burning supertanker and its spreading oil slick could block the route for other vessels. 1. Were terrorist pirates to hijack a large bulk carrier or oil tanker, sail it into one of the chokepoints, and scuttle it to block the sea-lane, the consequences for the global economy would be severe: a spike in oil prices, an increase in the cost of shipping due to the need to use alternate routes, congestion in sea-lanes and ports, more expensive maritime insurance, and probable environmental disaster. Worse yet would be several such attacks happening simultaneously in multiple locations worldwide. 2. The Strait of Hormuz, connecting the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea, is only 1.5 miles wide at its narrowest point. Roughly 15 million barrels of oil are shipped through it daily. In his 2003 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush revealed that U.S. forces had already prevented terrorist attacks on ships there. During the Iran-Iraq War, between 1984 and 1987, when tankers were frequently being attacked in the Strait of Hormuz, shipping in the Persian Gulf dropped by 25 percent, causing the United States to intervene militarily. Since then, the strait has been relatively safe, but the war on terrorism has brought new threats. 21-17 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies 3. Bab el Mandeb, the entrance to the Red Sea and a conduit for 3.3 million barrels per day, also is only 1.5 miles wide at its narrowest point. 4. The Bosporus, linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, is less than a mile wide in some areas; ten percent of the 50,000 ships that pass through it each year are tankers carrying Russian and Caspian oil. 5. According to the IMB, however, the most dangerous passage of all is the Strait of Malacca. Every day, a quarter of world trade, including half of all sea shipments of oil bound for eastern Asia and two-thirds of global shipments of liquefied natural gas, passes through this strait. Roughly 600 freighters loaded with everything from Japanese nuclear waste bound for reprocessing facilities in Europe to raw materials for China's booming economy traverse this chokepoint daily. Singapore's defense minister, Teo Chee Hean, has said that security along the strait is "not adequate" and that "no single state has the resources to deal effectively with this threat." Any disruption of shipping in the South China Sea would harm not only the economies of China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, but that of the United States as well. E. Ominously, there have been cases of terrorist pirates hijacking tankers in order to practice steering them through straits and crowded sea-lanes-the maritime equivalent of the September 11 hijackers' training in Florida flight schools. These apparent terrorists-in-training have questioned crews on how to operate ships but have shown little interest in how to dock them. In March 2003, an Indonesian chemical tanker, the Dewi Madrim, was hijacked off Indonesia. The ten armed men who seized the vessel steered it for an hour through the busy Strait of Malacca and then left the ship with equipment and technical documents. VI. NON-GOVERNMENTAL EFFORTS TO REDUCE MARITIME PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBEY AGAINST SHIPS A. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) in London has been dealing with the problem of piracy and armed robbery since 1983 when the IMO Assembly adopted its first resolution on the subject. Two further resolutions have been adopted by the IMO Assembly since that time, Resolution A.683(17) on "Prevention and Suppression of Acts of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships" in November 1991; and resolution A.738(18) on "Measures to Prevent and Suppress Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships" in November 1993. Both resolutions refer to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Since May 1991, IMO has been analyzing all reports of piracy and armed robbery and summaries are presented to the IMO Maritime Safety Committee for its 21-18 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection consideration. These maritime criminals are inclined to operate in waters where government presence is weak, often lacking in both technical resources and the political will to deal effectively with such attacks. International law permits any warship or government vessel to repress an attack in international waters. In a state's territorial waters, such attacks constitute an act of armed robbery and must be dealt with under the laws of the relevant coastal state. These laws seldom, if ever, permit a vessel or warship from another country to intervene. The most effective countermeasure strategy is to prevent criminals initial access to ports and vessels, and to demonstrate a consistent ability to respond rapidly and effectively to notification of such a security breach. B According to IMB’s Worldwide Maritime Piracy Report, it is necessary to suppress piracy and violent marine crime through anti-piracy and counter-piracy operations: “Anti-piracy training and operational security awareness should be conducted for vessel owners and vessel crew if they truly desire to rid themselves of their current “easy victim” status. Crisis Management and anti-piracy programs should be established and followed in order to reduce the vulnerability of the vessel. C. The following is a list of some of the ways of solving the problem of maritime piracy and related crimes, or at least decreasing the number of such attacks and their intensity: 1. Crew Security Awareness and Detection Training a. A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) supported by the proactive involvement of the crew to detect and deter attackers will dramatically increase the operational security of any vessel. The adversaries rely on three heavy fundamentals when attacking a vessel--Surprise, Speed, and Violence (or implied violence). When you take away the element of surprise, the adversary loses their biggest advantage. b. The vulnerability of any target is decreased when an active , rather than a passive, security solution is in effect.. This solution must be active and it must be detect to be effective. The ability to detect and deter should also be coupled with the ability to respond. An analysis of incident reports over the last five years shows that over 85% of all successful boardings were carried out with the attackers maintaining the element of surprise. Crew 21-19 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies Security Awareness and Detection Training is an inherent part of the anti-piracy plan, but the response is normally a function of a government agency. In order to decrease the number of piratical attacks and to increase the chances of catching the perpetrators, vessel crews need to be trained to defend themselves, and their vessel, may consider carrying arms on board in the case of an attack. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the moment a ship decides to offer an armed response, the risk of deadly violence escalates dramatically. This point is discussed in greater detail below. 2. Special Security Units: Increased Port Patrols a. Another way of decreasing maritime crime is through special security units. Such units have already been set up in Brazil, India and Thailand to protect vessels and their crews when they are in ports. To cover the expenses of increased patrol of its seaports the Brazilian Congress has approved an anti-piracy inspection fee. Vessels are charged for inspections each time they are made by the Port authorities. These charges have proved to be highly unpopular by Ship owners and other organizations like the Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO), Centro Nacional de Navegacao Transatlantic and the Brazilian Exporters Association. 3. 4. Expert Advisors a. The IMO is sending missions of experts to those countries where acts of piracy and armed robbery have most frequently been reported in order to further discuss the implementation in those countries of the IMO Guidelines for Preventing and Suppressing Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships. b. The missions are followed up by regional seminars intended to assist Governments and officials in the countries concerned in enhancing their capability for preventing and suppressing such unlawful acts in their waters. Reporting and Analysis Center. a. In 1992, the International Maritime Bureau established the Regional Piracy Center in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia as the world's first anti-piracy unit. The Center acts as an information and broadcast base that is responsible for monitoring piratical incidents worldwide by satellite services called INMARSAT-C and 21-20 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection NAVTEX. b. The Center, open 24 hours a day, serves as a liaison with law enforcement agents in Southeast Asia and offers its services to shippers free of charge. Reporting of incidents Ships are advised to maintain anti-piracy watches and report all piratical attacks and suspicious movements of craft to the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre, Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia . Tel + 60 3 2078 5763 Fax + 60 3 2078 5769 Telex MA 31880 IMBPCI E-mail IMBKL@icc-ccs.org 24 Hours Anti Piracy HELPLINE Tel: ++ 60 3 2031 0014 5. 6. The IMB has established a Rapid Response Investigation Service to secure prompt counter measures when merchant shipping comes under pirate attack. The two main tasks of this service are: a. Providing governments with prompt information about attacks so that they can take action against pirates without unduly delaying voyages b. To provide counseling for crew members who have been victims of pirate attacks."8 Armed Shipboard Personnel a.. b. One proposal suggests arming the officers and crews of merchant vessels traveling in waters known to be dangerous. Although this proposal might seem appealing when law enforcement assistance is not readily available, merchant mariners are not trained in the use of weapons. Added to the initial cost of purchasing weapons, the cost of training a vessel's crew to effectively repel pirate attacks is daunting. Aside from the initial expense for weapons, the crew would need weapons training as well as continued periodic training. Owners are unlikely to take on these extra costs in the highly competitive shipping market. Another strategy would be to employ 'sea-marshals' on board 21-21 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies merchant vessels. Their efforts would be analogous to the sky marshals used by the Federal Aviation Agency to deter and respond to airplane hijackings. The sea-marshals deployment could be focused on merchant ships transiting regions prone to piracy, or those ships that carry cargo favored by pirates. A problem with this plan is jurisdictional uncertainty regarding the marshal's authority to act against, or gain and maintain custody of, pirates on vessels in the territorial sea or internal waters of a coastal state. If the affected coastal state refused to recognize the authority of the flag state's sea-marshal, their deployment in the territory could be restricted. In the spring of 2000, a company was formed offering to deploy hired Nepalese Ghurkas aboard merchant vessels to deter pirates. 7. New Technology a. Anti-Piracy Tracking Devices (1) There are a number of reliable ship tracking devices available on the market today based upon Inmarsat and other satellite systems. An inexpensive anti-piracy tracking device system called SHIPLOC is one of these systems. This system requires only a (hidden) personal computer and internet access on board a vessel. (2) With the SHIPLOC system it can be tracked anywhere using a satellite to track the signal of the transmitter. By using a backup power-system it will keep emitting a signal even when the general power-supply on board is cut. SHIP LOC is fully compliant with the IMO Regulation SOLAS XI-2/6 adopted during the diplomatic conference in December 2002 that adopted the ISPS Code (see Maritime Security Module #272 for details), concerning a Ship Security Alert System. The ship security alert system regulation became effective on July 2004. It requires ships of over 500 GT to be equipped with an alarm system in order to reinforce ship security. The system allows the crew, in case of danger, to activate an alarm button that automatically sends a message to the ship owner and to competent authorities. The message is sent without being able to be detected by someone on-board or by other ships in the vicinity. SHIP LOC is contained in a small, discrete waterproof unit, which includes: an Argos transmitter, a GPS receiver, a battery pack in case of main power failure, and a flat antenna. 21-22 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection b. The Inventus UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) is a state-of-the-art reconnaissance system packaged in a highly efficient, highly stable flying wing form. Outfitted with cameras, the Inventus flies and covers a large ocean area and relays a real-time data link back to the ground station. This link provides real-time aerial surveillance and early warning of suspect or unauthorised craft movements to the coastal or law enforcement authority. Developed by Lew Aerospace, the Inventus is fully autonomous and can be launched and recovered even from a seagoing or patrol vessel. There are gas and electric formats and both fly in all weather conditions. Endorsed by the IMB the Inventus is yet another tool to aid in the maritime effort in its fight against piracy. c. Secure-Ship is perhaps the most creative innovation in the fight against piracy. It is a non-lethal, electrifying fence surrounding the whole ship, which has been specially adapted for maritime use. The fence uses 9,000-volt pulse to deter boarding attempts. An intruder coming in contact with the fence will receive an unpleasant non-lethal shock that will result in the intruder abandoning the attempted boarding. At the same time an alarm will go off, activating floodlights and a very loud siren. The IMB strongly recommends ship owners to install this device on board their ships. Further details can be obtained at www.secure-marine.com VII. GOVERNMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS A. Historically, sending naval units to piracy-prone regions has been an effective method to combat these international criminals. There have been suggestions that the international community form a multinational task force dedicated to antipirate patrols. Very few nations have the type of “blue water” navies required to conduct patrols at any distance from their own national waters. Moreover, coastal states might be reluctant to allow foreign warships from these large nations to operate within their territorial waters. As an alternative, in regions where piracy is a significant problem, the coastal states could create multilateral regional treaties to deal with their common piracy concerns. Since parties to this type of treaty would be limited to neighboring countries sharing a narrow, common goal, it seems more likely that a littoral state would tolerate an extraterritorial assertion of force within its borders. Such treaties would promote joint coordination and communication among the region’s navies and coast guards. Enhancing cooperation might also help to control sometimes more contentious issues such as illegal fishing and immigration. 21-23 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies Because international enforcement against acts of piracy is limited, some countries have taken matters into their own hands. In 1999 the tourist-conscious Greek government sent gunboats to discourage Albanian pirates from crossing the 3 km Corfu Channel to prey on yachts around the island. In addition, the continued rise in piracy prompted the Singapore Maritime Authority to release two separate advisories regarding preventative actions to take against sea robbery and piracy. The first advisory was issued on January 15, 1999, followed by another on January 18, 1999. WARNING ON PROTECTION OF STRAIT - NAJIB TELLS 'FOREIGN POWERS' NOT TO INTERFERE STRAITS TIMES - ASIA ^ | OCT 12, 2004 TUE KUALA LUMPUR - Foreign powers must not dictate how Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia protect the Strait of Malacca shipping lanes from threats of piracy and terrorism, Malaysia's Deputy Prime Minister said yesterday. 'The Strait of Malacca is ours to protect and preserve,' said Datuk Seri Najib Razak, who is also Defence Minister, at a conference on improving security in the pirate-infested waters. 'There are those who forget that the countries bordering the Strait of Malacca - each of them sovereign nations in their own right - have the ultimate say over the protection and preservation of the strait,' he said. Datuk Seri Najib did not name any country in his speech. However, Admiral Thomas Fargo, commander of United States forces in the Pacific, said in March that an American plan to heighten security in the Strait of Malacca might require a detachment of elite US troops to be stationed nearby. Datuk Seri Najib said any assumption that foreign countries whose ships pass through the Strait of Malacca can use them for military purposes 'reflects a lack of respect for the rights of littoral states and a misunderstanding of international law'. Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia all have littoral areas, or coastlines, along the Strait of Malacca. About 50,000 ships ply the narrow passage each year. The US has warned that terrorists could seize vessels for use as 'floating bombs' to blow up key ports or cities, although no such plots have been reported. Indonesia's navy chief, Admiral Bernard Kent Sondakh, said in a recent media interview that terrorism and piracy threats in the strait were overblown. 21-24 Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and the Terrorism Connection He suggested that foreign governments, including Washington, were playing up the threat because they were interested in controlling the waterway for economic reasons. 'The world economy is now moving toward the Asia-Pacific. Whoever controls the Malacca Strait, the Sunda Straits and the Makassar Straits controls the economy of the Asia Pacific,' Datuk Seri Najib said. The Sunda and Makassar straits are other waterways in the region. About 20 pirate attacks were reported in the Strait of Malacca in the first six months of this year. Joint naval patrols by the adjoining countries have curbed piracy, according to their officials. -- AP B. To curb piracy, authorities say the international community must first understand how serious a problem it has become. John Martin, a premier authority on piracy, said: "By continuing to develop close cooperation with local law enforcement agencies and giving them intelligence of better and better quality, they'll be able to move aggressively and make arrests. Better policing is the key.” Martin has also observed that "hard intelligence about any instance of piracy, no matter how minor, is the best weapon in the fight to make safer the dangerous waters of the modern world." C. Local enforcement has generally proven insufficient to deal with piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships outside local port areas, although in S.E. Asia Malaysia has increased its effectiveness in this area in recent years. Coordinated air surveillance and pursuit would be an important adjunct to local law enforcement efforts, but most countries — and particularly Indonesia — cannot afford the number of aircraft necessary to patrol their vast coastal region. D. To deal with the terrorism threat against ships, Canadian government agencies (including RCMP, Coast Guard, Border Services, Transport Canada and Canadian Forces) jointly staff marine security operations centers (MSOCs) on the East and West Coasts. Another is planned for the Great Lakes. Victoria's MSOC will be ready by summer 2005 (fully operational by 2010). According to Commander Al James, Canadian navy operations support centre, "Our big challenges besides seamless communications and procedures with our American counterparts will be getting people with the right expertise, and efficiently processing and sharing the growing body of incoming information." Although piracy and terrorism definitions often blur, the commonality is that each involves violent attacks that put people, vessels, cargo and the environment at risk. That most 21-25 Defense Institute of International Legal Studies attacks occur far from North America is of no comfort, according to scheduled speaker Craig Allen, a professor at the University of Washington law school. "We're already affected at home by higher insurance costs and restrictions on business practices," he said. "Mariners want prevention and security on the water, but I'm not hopeful this will happen to the extent they deserve." E. Another approach has led the United States and other maritime powers to press countries to ratify the 1988 Suppression of Unlawful Acts Convention (SUA Convention). Although the convention was developed in large part to combat terrorism, it is also being promoted as an anti-piracy measure. The SUA Convention would extend the rights of maritime forces to pursue terrorists, pirates and maritime criminals into foreign territorial waters. Some Southeast Asian countries are concerned that the SUA Convention provision could compromise national sovereignty. So far, only maritime powers such as the United States, Canada, major European countries, Australia, China and Japan have signed the convention. However, if piracy and terrorism are fused into a general threat, developing countries may find outside help easier to accept and sell to the public. So it may be in the interest of maritime powers to bring together piracy and terrorism to help persuade reluctant developing countries to let maritime powers pursue pirates and terrorists in their territorial and archipelagic waters. More information concerning the SUA Convention and other anti-terrorism conventions can be found in the Treaties Relating to Terrorism module # 250. VIII. CONCLUSION Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships is an age-old problem. Pirates have returned in ever increasing numbers in recent years. Combating piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships requires an international approach as recognized by the UN Law of the Sea Convention under which piracy is an international crime. Cooperative efforts by all nations to reduce piracy will once again be needed to solve this problem. Such cooperative efforts are proper because safety of the seas is a vital interest to all nations since so much of the world’s economy depends either directly or indirectly on maritime commerce. 21-26