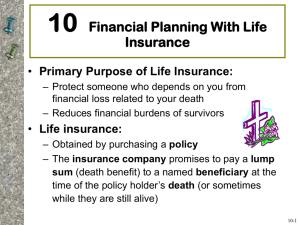

Definition of “life insurance” - Tax Policy website

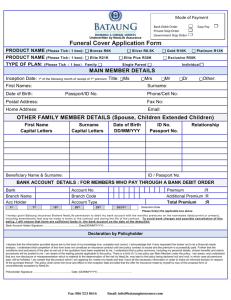

advertisement