HIS 377 - Universidad ORT Uruguay

advertisement

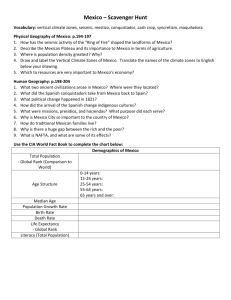

Globalization at work : Brief history of the “Maquiladora” Industry in Mexico Por Rodrigo Bonilla Hastings Licenciado en Historia y Ciencia Política, Maestría de Ciencia Política, Universidad de París I – Panthéon Sorbonne Recent globalization is a process that raises many issues. Whether is good or bad for development of nations and individuals is a constant debate. Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, ex-World Bank Chief executive and vice-president from 1997 to 2000, believes that: "I saw first hand the devastating effect that globalization can have on developing countries, and especially the poor within those countries."(2) This essay will try to illustrate how maquiladoras are a product and the living proof, of recent globalization (3). They are a result of it, and now portray its major characteristics. Through their study, the study of their history, their early development, their evolution, and their characteristics, it is possible to tackle the major problems and issues brought about by the recent and actual model of globalization. How do Maquiladora's represent globalization and its controversial issues? Firstly, it is fundamental to start by clearly defining the vast concept of globalization. Secondly, it seems necessary to try to find the historical roots of the maquiladora industry in Mexico. After which, the focus will be placed more specifically on the historical evolution of maquiladora industry in two different cities until recently. Finally, the problems raised by the maquiladora industry system will be presented in order to illustrate how this historical process reveals globalization's main contradictions. In order to work on the process of globalization, it is important to quickly set some parameters on its definition and chronology. What is globalization? Stiglitz defines it as: "The closer integration of the countries and peoples of the world brought about by the enormous reduction of costs of transportation and communication, and the breaking down of artificial barriers to the flows of goods, services, capital, knowledge, and people across borders."4 Globalization can be therefore understood as a process of growing interconnection between different actors or entities, that tend to unify the latter in a world-wide network. These actors and entities are: states, civil society, individuals, local or international organizations, firms, and companies. How long has this process been developing? It is a very long process that can be traced back to medieval or even ancient times. In this sense, Immanuel Wallerstein affirms: "The division of labor has always crossed borders and thus created networks of goods that respond exactly to the description of world production today. Today, we talk about 'global automobiles' because they are built from components that come from all over the world. Such was the case in the production of large ships during the XVII century"5. However, it is unquestionable that this process has known an unprecedented acceleration during the Twentieth century. A. Longchamp emphasizes the importance of both World Wars, in that they gave globalization the "technical and political tools" it needed to take-off: "electronics, computer science, air transportations."6 That said it is necessary to add that this recent globalization is also marked by the political and economic philosophy of neoliberalism. Its principles and ideals are presented in F.A. von Hayek's The Road of the Serfdom, 1944. This model presents the state as "an obstacle to development and liberty, therefore it must limit its prerogatives and promote in the contrary, freemarket"7. The supporters of this system had to wait for the consequences of the 1973 oil crisis, which put an end to almost 30 years of sustained prosperity in developed and developing countries, to start implementing their policies. The large Keynesian welfare state models implemented after the Second World War seemed to falter to the new phenomenon of stagflation. The new neoliberal policy makers strongly altered the state's role in economy and society. It had to "guarantee free-market mechanisms by reducing social spending, control popular discontent and assure monetary stability (...). The economic neoliberal agents (scholars, firms and financial institutions) played a major role in suggesting concrete measures concerning budget restrictions, the creation of an army of unemployed aiming to weaken unions, and fiscal reforms favorable to companies"8. This evolution in the role of the state is very important. The state is probably one of the actors most affected by the characteristics of recent globalization. This political institution administrates a precisely defined territory and population, using the legitimate use of physical violence in order to guarantee its functions. Recent globalization has hurt every single one of the elements that constitute it, as will be mentioned later on. How did the appearance of maquiladoras take place in such context? Maquiladoras9 appeared in the Mexican side of the US-Mexican border in the 1960s'. However, they are the result of a strong economic transformation in the region, mainly due to the Second World War. Historian David E. Lorey affirms: "The Second World War ushered in an era of unparalleled growth in the border region"10. The war deeply changed the economic activities of the border. On the U.S. side, the states of California, Arizona, Texas and New Mexico began to focus their activities on defense and high-technology. As for Mexico, the country was living what was later known as the 'Mexican miracle', a period of major economic prosperity, modernization and industrialization that went from 1940 to the 1960s'. The average GDP growth rate was of 6.3% from 1940 to 1968. Mexico's border states: Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua and Coahuila, played a major role in this period of economic growth. They received 50% of the country's new paved roads. This impulse of Mexico's nationalist government was strongly aided by two consequences of the war. Firstly, U.S. exports abroad decreased considerably, since the country's production was reserved for the war effort. This protected Mexican manufactured goods and therefore aided industrialization. Secondly, the war increased demand from the U.S. market, therefore raising the price of Mexican products. The state of Nuevo León and its capital Monterrey, became the heart of Mexico's heavy industry. They forged a strong entrepreneurial identity, rivaling the capital. As a larger and larger labor force developed, they were able to escape the government's official labor union, the Confederación de Trabajadores de México (CTM). Instead, they organized tamed company unions. Therefore, worker organization has traditionally been weak and has had trouble developing in the whole south border region. In 1965, the Mexican government established the Border Industrialization Program (BIP). It planned the creation of large numbers of assembly plants, that would import raw material from the U.S., assemble it into finish products, and export them back to the U.S. Unemployment was an issue at the time for two reasons: the Bracero program 11 was over and the traditional extractive industry was in crisis after the important changes in U.S. industry and the decrease of demand at the end of the Second World War. The BIP wanted to reverse this situation. Previously that same year, the United States had passed a tariff law, that exempted U.S. products, assembled outside the U.S., of general import duties. It was therefore possible to sharply lower the cost of assembling in the production process. It became considerably cheaper to send the raw material to Mexico, assemble it into finished product, and import it back, than to follow the whole process in the U.S. The BIP facilitated this process. Quickly, U.S. investment in Mexico shifted from traditional extraction industries, to manufacturing assembly plants and sometimes even production plants. The benefits of the maquiladoras were numerous and Lorey clearly presents them. Importation to the Mexican side of materials, supplies and machinery was duty-free as long as the whole of the product was for export. The only tax paid to enter the U.S. market was tax on value added, and not the general import duties. Maquilas were the only firms exempt of respecting the Mexican law requiring a majority of Mexican ownership in a firm. The U.S.’ advanced transportation infrastructure was very close, guaranteeing access by plane, road or train to any part of the U.S. market. As mentioned earlier, labor organization was weakly developed in the region, which guaranteed few strikes. This way, "maquiladora plants came to constitute an increasingly important link in the booming intra-industry trade reshaping global investment and commercial flows"12. It mainly took the form of twin cities: labor intensive on the Mexican side, development and capital intensive on the American side. With the introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement, signed in 1992 and adopted in 1994, by Canada, the U.S. and Mexico, the maquiladoras were boosted. The system was extended to new industrial activities (automobile industry) and to new regions of the country (Puebla, Toluca and León). The system was now institutionalized as Mexico's industrial model. Some remarks can be introduced concerning these early developments. How is globalization embodied here? How does it affect the region? Firstly, by the consequences of the Second World War in the US-Mexican border region. It wouldn't be utterly wrong to affirm that Adolph Hitler's invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939, had an indirect impact on the every day life of Mexicans and Americans on both sides of the border. Secondly, it is possible to note the beginning of recent globalization, with its neoliberal characteristics, through the BIP. The BIP is Mexico's reaction to adapt to a neoliberal globalization. It is a neoliberal reaction. First of all, it is opposed to the nationalist agenda that was initially held by previous Mexican governments since President Lázaro Cardenas and his major and symbolic nationalization of Mexican oil and expropriation and redistribution of land. This project wanted to make of Mexico a powerful, autonomous Latin American power, and was the ideological support of the "Mexican miracle". The law obliging firms in Mexican soil to be owned by a majority of Mexicans can be easily interpreted as the expression of this Mexican nationalist project (which is still present today, and visible through the current opposition to the privatization of state owned oil company, PEMEX). By exempting maquiladoras from this obligation, the government did not respect the nationalist project. This is illustrative of how an alternative model of development is progressively replaced by the neoliberal model of globalization, depicted earlier. The BIP includes more explicit neoliberal characteristics. The maquiladoras' legal framework is interesting because it virtually erases the presence of the state and its "obstacles": not only the law concerning Mexican ownership, but also, the absence of import duties, and the absence of proper labor protection. Through the BIP, the state is practically wiped out from the domains in which it is normally a present, active actor. The BIP assures more "freedom", guaranteeing the mechanisms of free-market, controlling popular discontent through the non-existence of effective unions. This is clearly in the line of thought of F.A. von Hayek, mentioned earlier. Once the origins of the maquiladora have been mentioned, it is important to study their development closely. It seems necessary to make a detailed description of maquiladoras and their development in the different regions where they appeared. The model was progressively "exported" from the border region to many other regions of the Mexican Republic, such as Yucatan, Aguascalientes and Guadalajara. In 2004, there were an estimated number of 2,805 maquiladora plants in Mexico, employing 1,1 million people.13 Some cities on the border have been dependent on maquiladora industry for half a century now. These maquiladora cities, illustrated by Ciudad Juarez, Tijuana or Matamoros, present the traditional development of the system and established its main characteristics. Scholar Maria Eugenia De La O clearly describes the historical evolution of maquiladora industry in Ciudad Juarez and the major changes it brought about 14. The introduction of maquiladoras radically changed the industrial productive pattern of the city and the state. Before the BIP, there were four major plants in Ciudad Juarez, dedicated to beer and whisky production and agriculture. In 1998, there were 23 industrial parks in Chihuahua, 18 of them in Ciudad Juarez, of which 16 were private owned and only 2 state-owned. Although traditional industries still remain, it is mainly electronics and automobile parts that characterize the city's production since the NAFTA treaty, with the presence of major foreign firms such as: Ford Motors Co. (4 maquiladoras), General Electric (3 maquiladoras), ThomsonRCA (2 maquiladoras) and others such as Epson and Toshiba America Co 15. The cities of Matamoros and Tijuana follow a similar pattern. Today, Ciudad Juarez is considered the "assembly capital" of the world, where, in 2004, 75% of the economically active population was directly or indirectly related to the maquiladoras. Maquiladora employees in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez account for 31% of the total number of maquiladora employees in the Republic. Maquiladora plants in these two cities account for 30% of the total 16. This evolution shows how the maquiladora system went from being a response to unemployment in the 1960s' to a proper model of national industrialization, consolidated during the 1980s' and reinforced after 1994 17. This reinforcement is also visible through the appearance of maquiladoras elsewhere throughout Mexico. The maquiladora industry in Yucatan complements richly the description above, and gives further insight on its strong connection to neoliberal globalization. Yucatan’s economy had been based on henequen plant 18 production for more than a century. A dramatic fall in the production of henequen in the early 1990s' left a massive amount of unemployed men that quickly filled in the first maquiladoras in the region 19. The Yucatan peninsula became a potential destination for maquiladora firms mostly for two reasons: it guaranteed a safer place for business than the traditionally dangerous border with the U.S. (Dinastía Mexicana, a subcontract jewelry firm of JC Penny & Macey's, moved from Ciudad Juarez to Yucatan in 1987) and a guaranteed relative proximity to the U.S. market. The port city of Progreso is only 970 km away from New Orleans, 1.060 km from Tampa and 1.170 km from Miami on a direct boat trip. Mexico City is more than 1.500 km on a sea-land trip. These were major attractions for foreign investment from everywhere around the globe. Although American and Mexican investment employs more than half the workforce, this region, has become a major international pole of activity. Investment from Hong Kong employs 23% of the population and owned the biggest plant in 1999, of multinational clothing firm Monty, employing 3.456 people in the city of Motul, northeast of Mérida. The Italian bathing-suit firm La Perla de Bolonia, arrived in view of penetrating the U.S. market after the signing of the NAFTA treaty. Morales, García and Pérez, can't be more emphatic on the situation in Yucatan: "The structural changes imposed by neoliberalism will accentuate the strategic dimension of the border in the internationalization of economy. [The border] will abide to trans-nationalizing and globalizing forces that will transform it and restructure it." The maquiladora industry is seen by them as one of the "axis of this globalizing process". These descriptions allow us to now analyze the major issues that this recent historical process has arisen. The recent globalization process produced maquiladoras, defined their characteristics, and established them as a durable model of industrialization in Mexico and Latin American. However, the results are questioned by many. Firstly, what was the real impact of maquiladoras in the economic development of Mexico? Secondly, what were its social consequences? It is possible to affirm that the maquiladora industry model had no relevant impact in reducing poverty and inequality in Mexico. Information from the World Bank tends to show that from 1994 until 2002, there haven't been any major changes 20. Extreme poverty was reduced back to the level previous to the shattering 1994-1995 financial crisis only in 2002. That is a 7-year-long recovery. In 2002, half of Mexico's population lived in poverty and a fifth in extreme poverty. Inequality in Mexico prevails and increased during the 1996-2002 period. During that period, the indicators of the INE or National Institute of Statistics show that maquiladoras present a slow but steady increase throughout the Republic 21. It can be affirmed therefore, that their impact wasn't relevant and that the model didn't solve Mexico's historical and serious problems of inequality, wealth redistribution, poverty and extreme poverty, as the supporters of the BIP and NAFTA loudly proclaimed it would. Secondly, the maquiladora system, although being now durably installed in Mexico, is characterized by irregularity and instability. It is naturally and strongly dependent on the economic and financial situation of the U.S. In recent history, it is possible to determine at least four major crises in the sector, that underline how limited such system really is as a long-term national industrial model. During the 1970s', the U.S. stumbled into a strong recession and an important number of maquiladoras shut down. Criticized for being a "volatile and short-sighted" system, those years were called the "Golondrina"22 years, making reference to the sporadic and opportunistic nature of such investments 23. Mexico was struck by a major financial and social crisis in 1982, U.S. investment in maquiladoras flooded in again, attracted by lowered wages and living standards (the latter guaranteeing a low level labor-related conflict). However, they retracted once again in the early 1990s' U.S. recession, to come back once more after the implementation of the NAFTA treaty in 1994. By 2001, maquiladoras were strongly consolidated, but the economic downturn following 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S., severely hit the sector. Accounting for 3,735 plants in 2001 before the attacks, the number hadn't recovered in 2004, with only 2,805 plants. As for the employees, it went from 1,3 million to 1,1 million from 2001 to 2004 24. These losses weren't only caused by the U.S. post-9/11 recession. It is another global factor, which remains until today probably the most serious one: competition from Asia and particularly China. Economic development specialist, scholar Daniel H. Rosen, points out Mexico's incapacity to stay competitive in relation to China: "from 1996-2002 Mexico's Global Competitive Report ranking fell seriously from 33 to 45, while China moved from 36 to 33. (...) China wins on low labor costs and many other costs of doing business, while quality control, technology diffusion, mid-level management skills, and physical infrastructure are improving fast enough to impress even skeptics and make Mexico's shortcomings in these areas more apparent. (...) So China is eating Mexico's lunch". He points out that it isn't China's cheaper workforce that causes China's competitiveness, but Mexico's "comparative disadvantages" such as corruption, poor infrastructure, underinvestment in human development and, he adds, revealing a neoliberal stance, "an intrusive bureaucracy (...) sometimes hostile to the private sector (...) and a less dynamic industrial structure reflecting imperfect intermediation and residual statism."25. However, Martínez gives pretty emphatic numbers concerning China's cheaper workforce: "In 2002 entry-level workers could be hired for as low as $0.25 (U.S.) an hour in Asia, compared to $1.50-$2.00 in Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez". He also points out the recent stability of the Mexican peso, new taxes and the prospect of new regulation as factors directing U.S. investment to Asia. Whether it is Mexico's industrial system's general lack of competitiveness or Asia's rock bottom wages, the maquiladora system is in crisis, once again. This renders evident its high sensibility to global economic changes, its superficial and ephemeral benefits for the population, what Martínez calls: "The acute vulnerability of the maquiladora industry to international wage competition and periodic global recessions"26. This has a third major economic drawback. Maquiladoras account for 50% of Mexico exports 27, which emphatically reveals the country's serious dependence towards this industry. Moreover, this dependence is not only towards an economic activity but also towards a country: 82.2% of Mexico's exports were destined to the U.S. market in 2007 28. The maquiladora system hasn't had any impact in solving Mexico's most serious problems. It has made the country highly vulnerable to international economic variations and particularly dependent to U.S. investment and economy. It is possible therefore to affirm that the system is precarious and doesn't benefit the country's long-term development or its population's. Furthermore, and as it will be mentioned bellow, the system has many questionable social consequences on the population. Maquiladora industry has guaranteed employment to thousands of Mexicans for decades now, albeit its volatility explained above. It has been very attractive and thousands of workers from everywhere in Mexico have moved North and to several of the new maquiladora regions. However, critics aiming at the social, cultural and environmental consequences of maquiladoras are numerous. This is well summed up by Martínez 29. The initial goal of the program was to employ men who were inactive after the end of the Bracero program in 1964 and the regions' general downturn, both mentioned earlier. However, the firms' and the program's concern was profit. Therefore, firms aimed at a docile and reliable work force in order to keep wages low and productivity high, hiring mostly women, who were indeed less prone to activism and effective on the job. With the system's consolidation however, that changed, and men progressively entered the sweatshops. The attraction of the maquiladoras produced a shortage in housing in most of the border cities, and the development of informal housing. Environment is a major issue. In a study issued by the Federal Ministry of Environment, Baja California and Chihuahua are the states with the higher percentage of companies producing toxic waste, with 51% and 20% respectively. Most of them are concentrated in their respective capitals, Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez. In total, the maquiladora industry produces 52,148 tons of waste a year. Some scholars go further affirming that 85% of pollution in the region of El Paso-Ciudad Juárez are produced by maquiladoras 30. As for working conditions and low wages, Carlsen, Wise and Salazár find that there are two major obstacles for their potential increase: the high mobility of the firms and the major obstacles for unionization. Behind relatively stable employment indicators, hides a different reality: firms shut down and new ones reopen constantly, thus imposing a high rotation level amongst the work force. This has many consequences that are beneficial for the employer and detrimental for the employee. The employer can maintain wages low, since the workers cannot obtain seniority and the consequent wage raises and benefits that come with it. A study presented by the authors, shows that in the period going from 1990 to 2000, for every three job creations in a maquiladora, one job was lost and for each maquiladora that opened, another one shut down. As for what goes on inside the gates of a maquiladora, the narratives of Lugo and Salzinger are quite enriching in describing how the inside organization of space and hierarchy also play in keeping the workers as divided as possible. Lugo mentions how the recurring lack of chairs plays an important role in establishing tension between the co-workers and therefore preventing them from forging solidarity ties 31. Finally, we can mention the cultural impact the maquiladoras can have on the population. Coming back to Yucatan, the henequen plant has been planted in the region for centuries and constitutes the basic element of Mayan and Lacandon culture in the peninsula. Albeit traumatizing events such as the Spanish conquest, they have been able to safeguard their traditions and culture. But will this be possible with important percentages of Native population moving to cities and working in maquiladoras. Judith Rosenberg quotes a good example of a Mexican peasant in San Gabriel Chilac, a small town near Puebla. After having sold a special flavored corn to Mexico City for decades, the NAFTA treaty impeded him of selling his product because he simply couldn't compete against cheaper hybrid corn produced by bigger producers from Mexico and the U.S.32. Will he be tempted to move to Puebla and find a job in a maquiladora? This presentation has illustrated how Mexico's recent history is entangled with that of the world, and this is a proof of how globalized the world is. The Second World War, the 1973 oil crisis, Osama Bin Laden´s attacks and China's economic aperture, all had impacts in the everyday lives of Mexicans. Mexico answered to the recent process of globalization by creating, in coordination with the U.S., the maquiladora industrial system. After developing in the U.S.-Mexican border region, it moved to other parts of the Republic. It was strongly consolidated by the NAFTA during the 1990s'. However, it still represents an inadequate answer to Mexico's structural problems and constitutes a fragile source of employment and long-term development. Moreover, it has proven to have negative social and cultural impacts. These considerations put into light how the recent history of globalization is a history of contradictions. This history shows how the model of globalization imposed by the "top" (multinational firms, international institutions such as the World Bank, the IMF or the Inter-American Development Bank, and governments) follows a neoliberal agenda that has serious problems answering to the problems of the "bottom". In light of these contradictions and the more recent financial melt down, the history of recent globalization shows a neoliberal model that has serious difficulties and needs serious change. Coming back to Stiglitz: "The way globalization has been managed, including the international trade agreements that have played such a large role in removing those barriers and the policies that have been imposed on developing countries in the process of globalization, need to be radically rethought."33 Notes: 1. Vargas Llosa, Mario. Globalization at Work – The Culture of Liberty. Catedra Siglo XX Lectures Series. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank. September 20, 2000. 2. Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. 2003. p.IX. 3. This will be the thesis of the following essay. However, I discovered further on during my readings, that this subject and this have been already tackled by Judith Rosenberg, of University of Texas at Austin, quoted in my bibliography. However, the approach is considerably different, as the reader will discover through his reading. 4. Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents. 2003: New York, W. W. Norton & Company Inc. p.9. 5. Immanuel Wallerstein, in Mutsaku Kamilamba, Kande, ed. La Globalización vista desde la periferia, Mexico: City: Grupo Editorial Porrúa, 2002. p.7. 6. A. Longchamp, in Mutsaku Kamilamba, Kande, ed. La Globalización vista desde la periferia, Mexico: City: Grupo Editorial Porrúa, 2002. p.7. 7. Mutsaku Kamilamba, Kande, ed. La Globalización vista desde la periferia, Mexico: City: Grupo Editorial Porrúa, 2002. p.9-10. 8. Mutsaku Kamilamba, Kande, ed. La Globalización vista desde la periferia, Mexico: City: Grupo Editorial Porrúa, 2002. p.9-10. 9. “The word ‘maquiladora’ developed from maquila, which meant a tax in kind that flourmills used to charge wheat farmes”. Rosenberg, Judith - The Rhetoric of Globalization: Can the Maquiladora Worker Speak? Dissertation Abstracts International, A: The Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 67, no. 12, pp. 4531. Jun 2007. p.3. 10. Lorey, David E. The U.S.-Mexican Border in the Twentieth Century - A History of Economic and Social Transformation. Delaware: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1999. pp.82-91. 11. Bracero program, 1942: US-Mexican coordinated emergency farm labor plan responding to shortage of labor on the U.S. side of the border caused by the War. Region farmers pressured the federal government for permission to import temporary workers. It was expanded to railroad workers in 1943. It was maintained, and with the Korean War, the Congress enacted Public Law 78 in 1951, prolonging it until 1954, after which it was constantly renewed until 1964. "This wartime flow of labor north to the US border states and beyond marked the beginning of the massive influx of Mexicans to both the Mexican and US border states. The northward movement of inexpensive Mexican labor, beginning as an implicit subsidy to US agriculture, would gradually mol the economic and social profile of the United States in the late twentieth century". Lorey, David E. p. 90. 12. Lorey, David E. p. 103-115 13. Martínez, Oscar J. Troublesome Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006. p. 111. 14. María Eugenia de la O, Ciudad Juárez: a pole of growth of maquiladora industry, in Quintero, Cirila, and María Eugenia de la O, eds. Globalización, trabajo y maquilas: Las Nuevas y Viejas Fronteras en México. Mexico City: Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2002. pp.25-71. 15. De La O: 40-34 16. Martínez, Oscar J. Troublesome Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006. p. 111 17. Carlsen, Laura, Tim Wise, and Hilda Salazár, eds. Enfrentando la Globalización - Respuestas Sociales a la Integración Económica de México. Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Porrúa, 2003. p.203. 18. Henequen: Agave whose leaves yield a fiber also called henequen which is suitable for rope and twine, but not of as high a quality as sisa. 19. Morales, Josefina, Ana García, Susana Pérez, Regional impact of the maquiladora in the Yucatán peninsula, in Quintero, Cirila, and María Eugenia de la O, eds. Globalización, trabajo y maquilas: Las Nuevas y Viejas Fronteras en México. Mexico City: Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2002. pp. 311-344. 20. The World Bank - Poverty in Mexico Fact Sheet. http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/LACEXT/M EXICOEXTN/0,,contentMDK:20233967~pagePK:141137~piPK:141127~theS itePK:338397,00.html 21. María Eugenia de la O, Ciudad Juárez: a pole of growth of maquiladora industry, in Quintero, Cirila, and María Eugenia de la O, eds. Globalización, trabajo y maquilas: Las Nuevas y Viejas Fronteras en México. Mexico City: Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2002. p.24. 22. Golondrina = a bird, a swallow. It is also known as hot money in Economics. 23. María Eugenia de la O, Ciudad Juárez: a pole of growth of maquiladora industry, in Quintero, Cirila, and María Eugenia de la O, eds. Globalización, trabajo y maquilas: Las Nuevas y Viejas Fronteras en México. Mexico City: Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2002. pp.32-33. 24. Martínez, Oscar J. Troublesome Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006. p. 111 25. Rosen, Daniel H., How China is eating Mexico's lunch. The International Economy. vol.17, n.2. ABI/INFORM Global. p. 22. Spring 2003. 26. Martínez, Oscar J. Troublesome Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006. p. 112 27. Rosen, Daniel H., How China is eating Mexico's lunch. The International Economy. vol.17, n.2. ABI/INFORM Global. p. 22. Spring 2003. 28. CIA - The World Fact Book: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mx.html 29. Martínez, Oscar J. Troublesome Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006. p. 112 30. Carlsen, Laura, Tim Wise, and Hilda Salazár, eds. Enfrentando la Globalización - Respuestas Sociales a la Integración Económica de México. Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Porrúa, 2003. pp.205-206. 31. Lugo, Alejandro. Fragmented Lives, Assembled Parts - Culture, Capitalism, and Conquest at the U.S.-Mexico Border. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008. pp.151-184. 32. Rosenberg, Judith - The Rhetoric of Globalization: Can the Maquiladora Worker Speak? Dissertation Abstracts International, A: The Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 67, no. 12, pp. 4531. Jun 2007. p.9. 33. Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc. 2003. pp.IX-X.