BLUEPRINT FOR SUCCESS: Infrastructure As The Engine For Jobs

advertisement

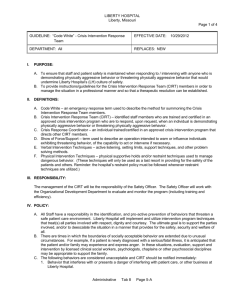

BLUEPRINT FOR SUCCESS INFRASTRUCTURE AS THE ENGINE F OR JOBS, ECONOMIC EXPANSION, AND GLOBAL COMPETITIVENESS A “WHITE PAPER” CREATED BY THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY ROUND TABLE SUMMER 2010 PROLOGUE THERE ARE FEW, IF ANY INDUSTRIES, IN AMERICA THAT PLAY A MORE FUNDAMENTAL AND IMPORTANT ROLE IN THE QUALITY OF LIFE OR STANDARD OF LIVING AMERICANS ENJOY, THEN THE DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY. FROM CONCEIVING AND BUILDING THE ROADS AND BRIDGES THAT TRANSPORT MILLIONS OF CITIZENS TO THE CLEAN WATER AND AIR WE DRINK AND BREATHE – EVERY ASPECT OF WHAT WE TAKE FOR GRANTED IN THE UNITED STATES HAD ITS INSPIRATION FROM THE INPUT OF DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS. INTRODUCTION It is axiomatic that timely, targeted, thoughtful (in the sense of meaningful, well planned and needed) infrastructure expenditures, whether private or publicly funded, are the blueprint for job creation,1 economic expansion,2 and long-term global competitiveness. 3 The very quality of life we enjoy as Americans is closely aligned to the state of our infrastructure assets and investments.4 When present, these elements are generally universally supported by policy makers and accepted by the public at large. When not, the opposite can occur and the valuable benefits derived from such expenditures are squandered.5 With so much at stake, it is imperative that as a nation, we get infrastructure investment right – not only for our current economic and job needs but also for our future prosperity. 1 Currently, approximately 9.0 million workers are employed in the construction industry. Studies vary as to the exact impact expenditures have on employment, but a USDOT 2008 update entitled: “Employment Impacts of Highway Infrastructure Investment” revising earlier reports puts the latest estimate at 34,779 jobs supported per billion dollars in new construction. The built environment represents some 50% of the nation’s physical wealth, and comprises roughly 6.0 percent of the current Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the U.S. at $850 billion – being larger than any manufacturing segment or agriculture. It is estimated that for every $1 billion spent on new construction in the United States it generates a total of $3.61 billion in economic activity encompassing a vast array of industries and services (Source: The Building Futures Council). 2 3 Worldwide the design/construction industry represents over 10 percent of the global economy with United States firms competing for projects with a growing number of foreign competitors. Yet, when U.S. firms, particularly design firms win oversea jobs, they are the “opening wedge” for other U.S. specified products and services (thereby greatly boosting U.S. exports). 4 Today the United States enjoys a quality of life unparalleled in all of human history. The diversity of products and foods brought to market, the ability to travel virtually at will, the eradication of most communicable diseases, and the goal to maintain a sustainable environment while meeting legitimate development needs, is only possible with the ingenious contributions of the Design/Construction community. It can be said, the work of a single sanitary engineer in devising a plan to eradicate deadly diseases has done more than all of the doctors combined who are called upon to treat the symptoms of that disease. To wit, the infamous “bridge to nowhere” and the less then well received “stimulus package” (see footnote on ARRA below). 5 BROAD-BASED SUPPORT The issue of infrastructure funding is not one of partisan debate, for it garners strong political support across party lines.6 Over the years, Presidents and Administrations of both political parties have spoken highly of the potential benefits to be obtained from infrastructure investments. Even before officially taking office, then President-elect Obama was in support of infrastructure expenditures saying in December 2008, “We will create millions of jobs by making the single largest new investment in our national infrastructure since the creation of the federal highway system in the 1950s.” It’s not surprising that the new President referenced the national interstate highway system as an example of the kind of success – targeted, well planned, & meaningful – infrastructure expenditures can have on the health and prosperity of the U.S. economy. And add to that – national security and military preparedness.7 Moreover, the conservative-leaning Investor’s Business Daily, while in strong opposition to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (“ARRA” aka the “stimulus package”) conceded in an editorial at the time “almost everyone agrees a little timely infrastructure might help. . .8 “ (February 10, 2009). So, the true challenge for infrastructure funding is not political – but rather one of proper stewardship/management and wise investment. 6 The last major piece of infrastructure legislation, The Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) overwhelmingly passed both houses of Congress in 2005 on huge bi-partisan votes. In the House, 412-8 (Roll no. 453) and in the Senate, 91-4 (Record Vote Number 220). Even the Water Resources Development Act of 2007, a bill vetoed by President Bush was passed by Congress in a bi-partisan show of strength resulting in both houses overriding the veto. [Passing by 2/3rds in the House 361- 54 (Roll No. 1040); and in the Senate by a vote of 79-14 (Record Vote Number 406)]. 7 President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law the Federal Highway Act of 1956, thus launching one of the most ambitious infrastructure endeavors in the nation’s history. It has been said of the system that: “As long as the Interstate is the highway supporting our society, economy, and national security, it will forever need to be the beneficiary of our attention and investment.” Dan McNichol, The Roads That Built America: The Incredible Story of the U.S. Interstate System, (2003). ARRA’s shortcoming was that it did not focus on timely, targeted, temporary infrastructure expenditures as advertised and “sold” to the American public [at best, the portion related to infrastructure dollars represented only about 19 percent of the overall $787 billion in cost for the bill (and about 30 percent of the spending side)] – thus its failure to create jobs and garner general public support are well documented. Even Democrat Senator Kent Conrad (ND) admitted there’s “a lot that really misses the mark” in the much-anticipated stimulus plan in that it holds none of the “timely, targeted [and] temporary” initiatives needed to jumpstart the economy. (Jan. 30, 2009, interview with CNBC Mad Money) 8 TIME FOR ACTION The time to begin a wise and thoughtful process of targeted and timely infrastructure investing is NOW.9 The United States economy/financial markets are in a slow recovery but sectors such as the design and construction community are still mired in a deep recession.10 The challenges we face to create a sustainable economic expansion and to meet global market competitors in the future, can be overcome with a commitment to infrastructure investment. No place is this commitment more needed then in the infrastructure challenges found in the transportation arena. The benefits and long-term return of such investments can be leveraged and multiplied throughout the economy if a smart targeted blueprint is followed that will create meaningful impact projects in its wake. 9 The CIRT Sentiment Index Report for the Q1-2010 asked the respondents to indicate the expected changes they foresaw with respect to F/T direct employees. While the results were better then for Q1-2009 in terms of how severe lay-offs would hit (i.e., greater then 10% vs. a more modest 0-5%), overall approximately 48% in both years saw some contraction rather than expansion of direct employment at CIRT’s leading firms. 10 The latest data places construction unemployment at 21.8% (or approximately 2.0 million workers) for April 2010 [Source: DOL, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A-14]; with construction put in place spending down to $847 billion on an annualized basis – off some 30.4% from its high in spring of 2006. [Source: U.S. Census Bureau of the Department of Commerce (March 2010)]. A BLUEPRINT FOR TRANSPORTATION EXPENDITURES Transportation infrastructure such as the Interstate Highway System are “signature” projects or programs that can far exceed the mere investment of funds to impact a greater expanse of American society, its economy, and even its security. These types of “major impact projects” can be both beneficial short-term investments and have a lasting high return – as such, they should be the focus of at least a portion of future transportation expenditures managed by the federal government. KEY ELEMENTS OF THE BLUEPRINT Based upon CIRT members’ collective experience and involvement with public infrastructure programs, the Round Table offers the following items for consideration and possible adoption in three broad issue areas: A) Reforming Grant Programs: 1. Establish clear highway congestion targets and tie discretionary funding to achievement of those targets. 2. Provide specific financial incentives for fast project delivery without cutting process corners. 3. Capitalize a major project fund with unspent earmarks. B) Testing New Approaches to Pre-Construction Processes: 1. 2. 3. 4. Performance Pilot Program. Mitigation-based alternative to NEPA. Authority to assume USDOT responsibilities under NEPA. Authority to “De-Federalize” projects with de minimis federal funding contributions. C) Expanding Project Finance Opportunities: 1. Increase size and flexibility of TIFIA program. 2. Eliminate the private activity bond ceiling and include a private activity component of Build America Bonds. 3. Expand tolling authority on interstate highways. TRANSPORTATION ISSUES BACKGROUND While much of the Washington-based transportation lobbying community is focused on the specific dollar size of federal surface transportation programs, relatively little attention is being paid to a far more serious policy failure – namely our growing inability as a country to deliver major projects (those exceeding $250M in cost). Today, 10 years or longer is the standard timeframe to deliver a major project from concept to completion even if there is a large public consensus on the urgency for the investment. This delays the realization of benefits for many years and undermines public confidence in transportation investments. It is also not consistent with best practices around the globe, including in countries with strong environmental laws and regulations. When properly selected (not through earmarks or based on other political influence), major projects produce disproportionate economic and employment benefits relative to the types of projects that were funded by the stimulus [only about 20% of the money included in ARRA was for infrastructure – mostly “shovel ready” types of projects which would not be traditionally defined as major projects]. The benefits of these projects are longer lasting and can help transform local economies. Unfortunately, the country’s current major projects strategy is almost entirely focused on preventing waste, fraud and abuse, not actually advancing meritorious, high impact projects. In other words, the policy is 100% focused on defense with little concern for playing offense and driving these projects to completion. It is obviously important to do everything to prevent cost overruns, delays and corruption, but such a focus need not be mutually exclusive of a new focus on actually getting large scale projects across the finish line. POLICY INITIATIVE With this document, the CIRT is calling on the country to develop a proactive major transportation projects policy. We believe these projects deserve special legislative consideration, and we propose a series of legislative reforms to underpin this policy. CIRT also believes these reforms can either proceed on a stand-alone basis or as part of the long-term reauthorization process now underway. CIRT appreciates that some of these concepts may be controversial, and as a result, we believe an experimental approach may be necessary. Notwithstanding, CIRT contends that in the long term a new policy framework could be win/win to both developers and those concerned about protecting resources and public input. However, we acknowledge that this premise must be tested in the real world, and as a result, many of our recommendations take the form of pilot approaches. Outlined below are the key reform elements: A) Program Reforms: 1) Establish clear highway congestion targets and tie discretionary funding to achievement of those targets. Today, the federal government requires that congested areas establish so-called “Congestion Management Process.” The USDOT says that the CMP “presents a systematic process for managing traffic congestion and provides information on transportation system performance.” As is often true with the federal transportation program, a seemingly well intentioned requirement has become a paperwork exercise with marginal impact on transportation decision-making. Instead of a paperwork exercise, the federal government should require meaningful congestion reduction targets be established and should tie the receipt of discretionary federal funding to the realization of these targets. A meaningful requirement would likely be opposed by the States (all of whom are projecting that congestion will be worse in the future than it is today), however, the federal government should insist on results in connection with its investments, not simply paperwork. A program shift to specifically emphasize congestion would have a clear impact on the development and emphasis on major projects in congested areas. These projects, particularly when combined with some form of variable tolling, are often the only means to achieve sustainable congestion relief in capacity constrained regions. 2) Provide specific financial incentives for fast project delivery without cutting process corners. Today, the federal government provides extra oversight to major projects through its “major projects team”. This heightened emphasis on project oversight came about as a response to growing concerns about cost overruns on federally funded projects, including the so-called “Big Dig” in Massachusetts. This effort, along with continued emphasis on major project waste, fraud and abuse by the Department’s Inspector General, has had a positive impact on reducing corruption and losses associated with poor project accountability. There is no reason, however, that the federal government cannot also provide provided clear financial incentives to states to expedite pre-development processes and decisions for selected major projects consistent with other oversight requirements. In other words, the federal government should promote reaching good decisions faster. Such a shift in policy could have a substantial impact on the importance that these projects take in connection with managing state and metropolitan programs, since today the major project equation is one rife with downside risks in which “taking it slow” is often the preferred course of action. Under the incentive program, USDOT could solicit nominations for major projects that would “compete for speed” with grants, credit assistance and regulatory flexibility provided in exchange for hitting various agreed upon milestones through the project development process. These milestones would be established at timeframes between 40 and 60% sooner than the average timeframe for a comparably-sized major project [Might want to include a pullout anecdote supplied by one of the companies to give a sense for how long current process is]. 3) Capitalize a major project fund with unspent earmarks. Billions of dollars of unspent earmarks currently remain on the books at USDOT. This happens for one of two reasons: 1) there are no state and local matching resources available to satisfy federal matching requirements; or 2) the earmarked project is a low priority for the state/local government and is therefore deferred indefinitely. Instead of allowing this wasteful practice to continue, earmarks that remain unspent after 3 years should be re-allocated to a “major projects fund” whose purpose is to identify and help finance high impact, large scale projects and to leverage non-federal sources. Over time, if the practice of earmarking continues, unspent funds should continue to flow to this major projects fund. Administration of the fund’s investments should be coordinated with the TIFIA program, as well, in order to maximize support for major projects. This concept should also help restore some of the collapsed public confidence that has taken hold following the large number of wasteful projects funded in SAFETEA-LU. B) Testing New Approaches to Pre-Construction Process Requirements: Pre-construction federal process requirements are extremely complex and poorly understood. Ironically, the requirements are designed in part to ensure adequate public input into the development of federally funded projects. The reality, however, is the process imposes huge costs on major project sponsors with very little public understanding of the actual nature of the process. It is not at all clear that those costs are justified by the benefits or that alternative approaches would not yield comparable environmental protections at far less cost. The country badly needs to test new ideas and learn from those experiments. 1) Performance Pilot Program. An increasingly accepted critique of the federal surface transportation program is that the program is excessively focused on processes and not outcomes. Unfortunately, many of the proposals designed to address this failure would simply attempt to federalize outcomes and make few meaningful changes to current process requirements. A better approach would be for the federal government to allow up to 3 states or authorized major metropolitan areas to enter into a “performance contract” with the federal government covering their entire transportation systems. This contract would lay out a variety of performance requirements that the jurisdictions committed to achieving (congestion, safety, reliability, air quality, etc.), and in exchange, the federal government would: a) provide federal funds in flexible block grant form; b) allow states to develop their own planning and air quality processes; and c) allow state environmental protections to govern the majority of project decisions. 2) Mitigation-based alternative to NEPA. The average federal environmental impact statement for a major surface transportation project takes over 60 months to finalize today. In most instances, this is not as a result of the difficulty of assessing impacts, but rather because the NEPA process has become the process to debate the merits of the project and to negotiate mitigation of project impacts. Unfortunately, this complex negotiation does not vest authority to consent with any of the stakeholders participating. In other words, a sponsor could reach agreement with a party seeking a certain mitigation package only to have another party assert a different or even conflicting set of mitigation objectives. Without any authority to reach a binding agreement, sponsors perform the ultimate cat herding exercise that can take many, many years. As delays mount, the cost of mitigation increases and the project can actually support less mitigation by the time it finally moves forward than it otherwise could have under a more certain and less time consuming approach. All parties can thus lose under this approach. The USDOT should be authorized by Congress to experiment with an alternative convening process on a select number of significant major projects. Such a process could be modeled somewhat after the way negotiated rulemakings are conducted. USDOT would convene project sponsors and relevant stakeholders using an early assessment of impacts and would facilitate a negotiation on the best approaches to mitigation. Sponsors and stakeholders would be free to propose a wide range of mitigation strategies. The USDOT would establish a timeframe for the discussion (6-9 months), and if agreement could be reached in advance of such timeframe, that agreement would be binding (no litigation) and satisfy all NEPA requirements. In essence, this process would allow the array of costs associated with delay to be recaptured and shared between sponsor and impacted stakeholder, whereas under the current approach, stakeholders are left to use delay itself as their best tactic. Often, they succeed at delaying a project, only to have it ultimately built with less capital to contribute to mitigation - thereby leaving all parties worse off. 3) Authority to assume USDOT responsibilities under NEPA. SAFETEA-LU created a pilot program permitting up to 5 states to assume USDOT authorities under NEPA. Only California was able to execute the requisite agreement with USDOT prior to the program’s cutoff date due in part to the rigid audit requirements that were associated with the pilot. The pilot should be extended and the audit requirements should be revised to focus simply on capacity of the jurisdiction to implement the responsibilities. 4) Authority to “De-Federalize” projects with de minimis federal funding contributions. Today, many major projects are being developed with only a small percentage of funding being contributed by the federal government. Despite the small capital contribution, the federal government still asserts authority over all project development requirements (planning, environmental review, procurement, etc.). States and localities should be authorized to pursue projects based solely on state requirements to the extent the federal government is contributing less than 15% of the project’s total costs. C) Expanding Project Finance Opportunities: 1) Increase size and flexibility of TIFIA program. The federal credit program known as TIFIA has become a fundamental part of the financing strategy for major projects across the U.S. In fact, the majority of greenfield toll road projects in the U.S. are being developed using this program, and increasingly transit system are utilizing this financing tool Unfortunately, the program’s relatively modest budget ($130M/year approx.) is now oversubscribed, leaving many major projects in the waiting line for months and potentially years. With a small increase in funding to $500M/year, this would largely eliminate the current scarcity in program resources will a negligible impact on the overall federal-aid program. In addition to new budgetary resources, the program should be given flexibility to fund more than 1/3 of total project costs in connection with certain large scale projects in which other lenders may be reluctant to participate. In these cases, 50% of project costs funded by TIFIA is a reasonable policy position, and we would endorse a statutory change to address this. 2) Eliminate the private activity bond ceiling and include a private activity component of Build America Bonds. SAFETEA-LU amended federal tax law to permit up to $15 billion in private activity bonds to issued for surface transportation projects. Under these rules, a public authority is permitted to issue bonds and turn over the proceeds to a private developer so long as the project financed with the proceeds is a public use facility (public highway, transit system, etc.). This legal change has already been critical in advancing 3 major highway projects in the last 3 years with significantly more projects in the line as more and more private investors look to invest in surface transportation projects. In fact, increasingly, large scale projects are utilizing private activity bonds and TIFIA together. Eliminating the cap on this $15 billion would ensure that no major projects in the future are stalled because of a lack of issuing authority. In addition to private activity bonds, Build America Bonds have become an increasingly important part of State and local infrastructure financing. Current law does not permit the Build America Bond proceeds to be turned over to a private developer in connection with a public use infrastructure project as is permitted under the private activity bond authority. If the program is continued, a change in law that would allow equal treatment of major public private partnership projects would stimulate additional investment. 3) Expand tolling authority on interstate highways. An growing number of states are exploring the idea of tolling interstate highways in order to manage traffic flows and generate revenues for re-investment. Federal law today is excessively restrictive and requires states to apply under a variety of pilot programs designed in an era when tolling was more complicated administratively. Today, tolls can be collected as easily as gas taxes using new electronic tolling technologies that permit vehicles to travel at highway speeds at all times. Federal tolling policy should reflect this new technological reality, not constrain the ability of states to finance and operate their road networks.