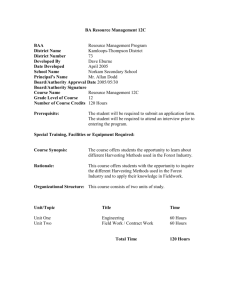

1 - Tabi

advertisement