Exchange Rate Determination

advertisement

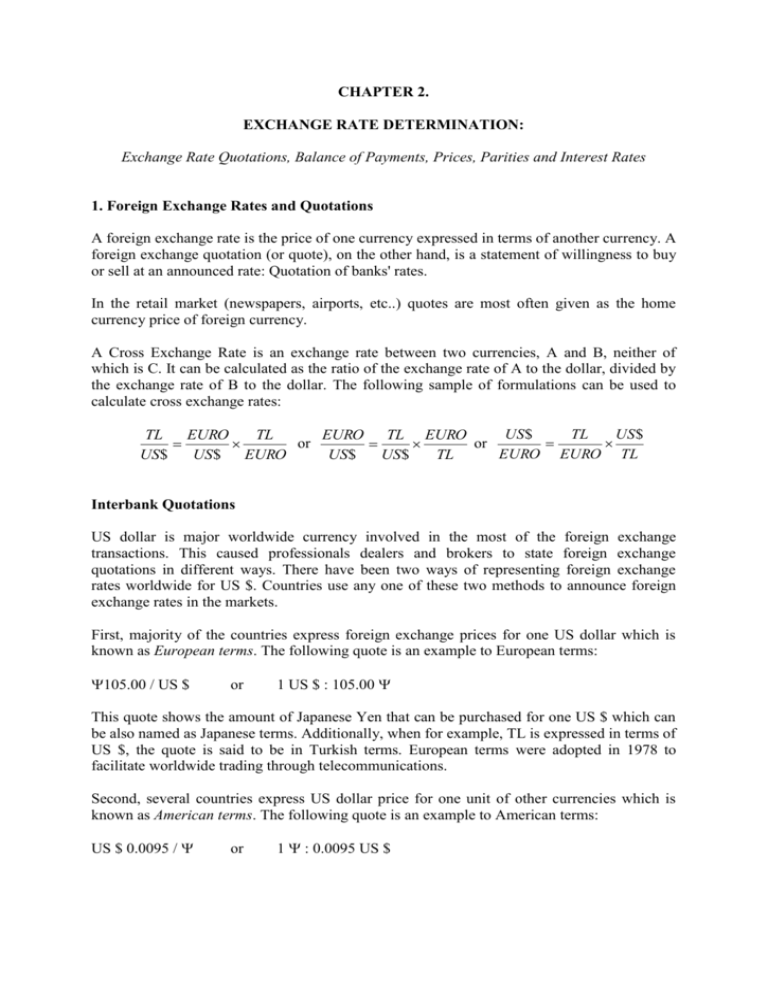

CHAPTER 2. EXCHANGE RATE DETERMINATION: Exchange Rate Quotations, Balance of Payments, Prices, Parities and Interest Rates 1. Foreign Exchange Rates and Quotations A foreign exchange rate is the price of one currency expressed in terms of another currency. A foreign exchange quotation (or quote), on the other hand, is a statement of willingness to buy or sell at an announced rate: Quotation of banks' rates. In the retail market (newspapers, airports, etc..) quotes are most often given as the home currency price of foreign currency. A Cross Exchange Rate is an exchange rate between two currencies, A and B, neither of which is C. It can be calculated as the ratio of the exchange rate of A to the dollar, divided by the exchange rate of B to the dollar. The following sample of formulations can be used to calculate cross exchange rates: US $ TL US $ TL EURO TL EURO TL EURO or or EURO EURO TL US$ US$ EURO US$ US$ TL Interbank Quotations US dollar is major worldwide currency involved in the most of the foreign exchange transactions. This caused professionals dealers and brokers to state foreign exchange quotations in different ways. There have been two ways of representing foreign exchange rates worldwide for US $. Countries use any one of these two methods to announce foreign exchange rates in the markets. First, majority of the countries express foreign exchange prices for one US dollar which is known as European terms. The following quote is an example to European terms: 105.00 / US $ or 1 US $ : 105.00 This quote shows the amount of Japanese Yen that can be purchased for one US $ which can be also named as Japanese terms. Additionally, when for example, TL is expressed in terms of US $, the quote is said to be in Turkish terms. European terms were adopted in 1978 to facilitate worldwide trading through telecommunications. Second, several countries express US dollar price for one unit of other currencies which is known as American terms. The following quote is an example to American terms: US $ 0.0095 / or 1 : 0.0095 US $ The above quote shows the amount of US $ that can be purchased for one Japanese Yen which can be calculated by taking the reciprocal of the rate presented in European terms. Therefore, 1 US$ 0.0095 / Yen Yen 105.00 / US$ American terms of presenting quotes are used for the U.K. pound sterling, the euro, Australian dollar, New Zealand dollar and Irish punt. Direct and Indirect Quotas Foreign exchange rates can be expressed in terms of currencies other than US$. There are two common methods other than European and American terms: Direct quote and Indirect quote. A direct quote is a quotation expressing home currency price in terms of a foreign currency where an indirect quota is a quotations expressing foreign currency price in terms of a home currency. Consider the following rates: EURO 1.47 / GBP or 1 GBP: 1.47 EURO This rate shows the amount of EURO that can be purchased for one British pound sterling. It is a direct quote in EURO area showing the internal value of EURO for one unit of pound sterling and is an indirect quote in U.K. showing the external value of British pound sterling against EURO. Taking the reciprocal of this quotation, we get: GBP 0.68 / EURO or 1 EURO: 0.68 GBP This quotation shows the amount of GBP that can be purchased for one EURO. It is this time a direct quote in U.K. showing the internal value of GBP for one unit of EURO and is an indirect quote in the EURO area showing the external value of EURO against GBP. Bid and Ask (offer) Quotations Interbank quotations are given as a bid and ask. A bid is the price in one currency at which a dealer will buy another currency. On the other hand, an offer (ask) is the price at which a dealer will sell the other currency. To make profit, bid price is greater than ask price. The difference between the two will give the spread (profit). Bid of one currency is the offer of opposite currency at the same time. A trader seeking to buy $ with EURO is simultaneously offering to sell EURO for $. Outright quotations, that full price to all of its decimal points is given, can be given in a few methods in worldwide video screens: Exhibit 2.1 Outright Quotations in the Interbank Market Method 1. Method 2. Method 3. Bid – Ask (Yen/US $) 118.27 – 118.37 118.27 – 37 27 - 37 Quotes can be given in the first term (bid) as 118.27. In the second term (offer), they may be given as 118.27 – 37 on a video screen. Or 27 to 37 assuming that leading digits (118.) are already known. The last 2 digits are small figure frequently changing, while leading digits are big figures seldom changing. When quotations are converted from European terms into American terms, bid and offer reverse. Reciprocal of bid becomes offer and reciprocal of offer becomes bid. To make a profit, offer price should be greater than the bid price. Consider the following quotes in Table XX: Exhibit 2.2 Bid and Ask Quotations in European and American Terms European Quote American Quote Bid ¥ 118.27 / $ $ 0.0084 / ¥ Ask ¥ 118.37 / $ $ 0.0085 / ¥ Spread ¥ 0.10 / $ $ 0.0001 / ¥ Reciprocal of bid quotes in European terms becomes ask in American terms. Spread (profit) in European terms is ¥ 0.10 / $ in European terms where it is $ 0.0001 / ¥ American terms. Expressing Forward Quotations on a Points Basis Traders usually quote forward rates in terms of points (swap rates). A point is the last digit of a quotation. Currency prices for $ are usually expressed to 4 decimal points. A point = 0.0001 of most currencies. Japanese Yen and Italian Lira are quoted to 2 points. A forward quotation expressed in points is not a foreign exchange rate as such. It is the difference between the forward rate and the spot rate. Traders follow an operational rule that indicates whether forward quote is at a premium or a discount. More specifically, if bid in points is greater than offer in points, forward rate is said to be at a discount and points should be subtracted from spot rate. On the other hand, if bid in points is less than offer in points, forward rate is said to be at a premium and points should be added to spot rate. A forward bid and offer quotation expressed in points is also called a swap rate (Borrowing a short term loan of one currency at another currency's rate). Consider Table XX below: Exhibit 2.3 Spot and Forward Quotations for the EURO and Japanese Yen Euro: Spot and Forward ($/є) Term Cash Rates Mid-Rate Bid Ask Yen: Spot and Forward (¥/$) Mid-Rate Bid Ask Spot 1.0899 1.0897 1.0901 118.32 118.27 118.37 1 Week 1 month 2 month 3 month 4 month 5 month 6 month 1 year 1.0903 1.0917 1.0934 1.0953 1.0973 1.0992 1.1012 1.1143 3 17 35 53 72 90 112 242 4 19 36 54 76 95 113 245 118.23 117.82 117.38 116.91 116.40 115.94 115.45 112.50 -10 -51 -95 -143 -195 -240 -288 -584 -9 -50 -93 -140 -190 -237 -287 -581 Source: Bloomberg, March 22, 1999. Mid-Rate is the numerical average of Bid and Ask. Spot rates for $/є and ¥/$ quotations are given in Table XX. Point quotations of forward rates are given for 1 week, 1-6 months and 1 year periods. Positive cash rates for the forward market indicate that ask prices are higher than bid prices therefore they should be added to the spot rates. Negative cash rates indicate that bid prices are higher than ask prices and they should be subtracted from the spot rates. For example, 6 month forward rate for $/є quotation can be calculated as follow: Spot Plus 6 month cash rate 6 month forward rate: Bid 1.0897 + 112 1.1009 Ask 1.0901 + 113 1.1014 Here, for example, cash rate for bid price can be assumed as 0.0112 and added to the spot rate and ask price as 0.0113. The mid rate would be average of 1.1009 and 1.1014 equaling 1.10115 which is rounded to 1.1012 in Table XX. Forward Quotations in Percentage Terms Forward quotations can be represented as percentage terms per annum which simply show a deviation from the spot rates per annum. This method facilitates comparing premiums or discounts in the forward market. The percent premium or discount depends on which currency is the home, or base, currency. Consider the following table: Exhibit 2.4 Spot and Forward Quotations as Percentage Terms Quotation Given as Foreign Currency/ Home Currency/ Home Currency Foreign Currency $ 1.0897 / є є 0.9177 / $ Spot Rate $ 1.1009 / є є 0.9083 / $ 3-month forward rate Here EURO currency is assumed as home currency where U.S. dollar is assumed as foreign currency. Then, percentage terms take the following forms: Indirect Quotations (In terms of Home Currency, $/ є) When indirect quotation is used, percentage change per annum is calculated as following: The formula for percent premium or discount (f) = spot forward 360 100 forward n where n represents the number of days in this case. But when for example numerator is 12, n might be also the number of months. The percentage change here will be: f = 1.0897 1.1009 360 100 4.10 % p.a. 1.1009 90 (per annum) For three months forward, the sign is negative indicating that the forward dollar is selling at a 1.02% per annum at a discount over EURO. Direct Quotations (In terms of Foreign Currency, є / $) f = forward spot 360 0.9083 0.9177 360 100 100 4.10 % p.a. spot n 0.9177 90 For three months forward, the sign is again negative indicating that the forward dollar is selling at a 2.32% discount per annum over the EURO. The result is the same with the previous answer. Percentage Changes Over a Particular Period: Calculation of Devaluation / Revaluation If the number of periods and n is eliminated from the formulas in the previous section, then percentage terms regarding the particular period but not per annum. Assuming the following exchange rate for TL / $: January – 2004 January - 2005 1 $ : 1,400,000 TL 1 $ : 2,950,000 TL In this period, TL has depreciated against US $. And US $ has appreciated against TL. Degree of percentage change is then = x1 x 0 2,950 ,000 1,400 ,000 100 100 110 .7% x0 1,400 ,000 Here we see that during two months’ period, US $ has appreciated against TL by 110.7 %. At a first look, we can also say that TL has also depreciated against US $ by 110.7 % in our everyday life. But in reality, in terms of purchasing power parity, this is not true. Because, in terms of PPP, no currency unit can loose its value 100% or higher. Otherwise, TL should be withdrawn from the market, meaning “zero” PP. So; Degree of devaluation/depreciation = 1 1 x1 x 0 x x1 1,400 ,000 2,950 ,000 100 0 100 100 52 .5% 1 x1 2,950 ,000 x0 So, we can now say that TL has depreciated by 52.5% against US $. May be we’ll buy only a bread by 1 billion TL in USA but it never reaches 99% depreciation. Another explanation to this theory is that according to $ terms, TL depreciated by 52.5% while $ appreciated by 110.7% according to TL terms. 1. Balance Of Payments and Exchange Rates A nation’s economic performance is best viewed in BOP data. It is a statistical statement that systematically summarizes, for a specified time period, the economic transactions of an economy with the rest of the world. Economic transactions include exports, imports, income flows, capital flows, gifts and similar one-sided transfer payments. The net of all of these transactions is matched by a change in the country’s international monetary reserves. BOP are important to business managers, investors, consumers, and government officials because the data influence and are influenced by other key macroeconomic variables such as GDP, employment, price levels, etc.. Monetary and fiscal policy must take BOP into account at the national level. BOP helps to forecast a country’s market potential, especially in the short run. A country experiencing a serious BOP deficit is not likely to expand imports. BOP is an indicator of pressure for a country’s foreign exchange and for a firm for foreign exchange gains or losses. 1.1 Measuring a Nation’s Performance: Deficits and Surpluses in BOP BOP measures, summarizes and states all the financial and economic transactions between residents of one country and residents of the rest of the world. If a nation receives less than what it spends, then it incurs a “deficit”. If a nation receives from abroad more than it spends, then it incurs a “surplus”. Credits: Foreign Exchange Earned Transactions that earn foreign exchange are recorded in BOP as a “credit” with a (+) sign. Credits are obtained by selling to non-residents either real or financial assets or services. Ex. Borrowing, Exports and foreign students university fees, etc.. Debits: Foreign Exchange Expended Transactions that expend foreign exchange are recorded as “debits” and are marked as (-) sign. Ex. Imports, purchasing foreign services (insurance), lending, host country student fees for foreign schools, etc… BOP is systematically defined and summarized by International Monetary Fund (IMF) institution by setting up its own standard in representing BOP for the countries. According to IMF classification of BOP, there are 43 lines representing economic transactions of the countries. The following sections of BOP are defined based on IMF classification of BOP: Current Account – Group A Current account is the most liquid and important part of BOP covering transactions of trade on goods and services, trade on services and transfers. Basically, balance on goods and services, income and transfers are recorded in current account. Current account balance in BOP data is recorded in line 1 according to the IMF classification. Current account can be categorized as followings: Line 4: Balance on Goods: Referred to as trade balance: exports – imports Service Balance: For those countries having large service sectors like USA and Japan, merchandise trade balance is not the most important. For these countries services sector constitute a significant portion of BOP. Selling services to foreigners entered as Credits Purchasing services from abroad entered as Debits Services are sometimes referred to as Invisible Trade. Line 7: Balance on Goods and Services Income Balance: Investment Income: flow of earnings from direct and portfolio investments, entered as credit. Compensation of employees: wages, salaries, other benefits, entered as debit. Balance on Goods, Services and Income: Trade Balance – Service balance – Income Balance Balance on Current Transfer Including sums sent home migrants, permanent workers abroad (professors, business executives), parental payments to students abroad, research grants, etc…. Balance on Current Account - Group A Trade Balance – Services Balance – Income balance – Transfer Balance Capital Account - Group B It measures capital transfers and the acquisition or disposal of non-produced and non-financial assets. Capital transfers transfer of ownership of fixed assets, transfer of funds, the cancellation of liabilities by creditors. It also includes both governmental and private debts. Non-produced and non-financial assets intangibles like patented entities, leases, transferable contracts, and goodwill. Financial Account - Group C It provides data on long term financial flows such as foreign direct investments, portfolio investments, and other long term capital movements. Direct investments abroad (-) Foreign Direct Investment (+) Portfolio and other investments purchases and sales of equity and debt securities, changes in trade credit, loans, currency, and deposits. Group A + Group B + Group C = Basic Balance Net Errors and Omissions - Group D It reflects the transactions that are known to have occurred but for which no specific measure was made. They are recorded to prevent imbalances in BOP. Ex. Drugs, narcotics in imports, etc… Total, Groups A through D Also called the overall balance, or the official settlements balance. It is the net result of trading, capital and financial activities. It is the sum of all autonomous transactions that must be financed by the use of official reserves or other non-reserve official transactions. Reserves and Related Items - Group E The net result of the overall balance must be financed by the changes in official monetary reserves. The sum of changes in reserves on line 39 is identical to the total change in foreign exchange reserve position reported on line 38. 1.2 Approaches in Balancing BOP The basic aim of countries is to arrive at a zero balance in their BOP. But having a zero balance in BOP is almost impossible for countries. It is not so easy to balance foreign-based expenditures with foreign-based receipts. Imbalances in BOP will affect the whole economy of countries and their relationships with the world. There are various policies that countries may follow in case of imbalances (surpluses or deficits) in BOP. If there are temporary deficits in BOP, these deficits could be financed by reserves or to apply a repairing policy. But if deficits are chronic or continuous, then financing through reserves might not be possible; because the international reserves of countries are not unlimited. One of the ways to put a pressure on BOP deficits is to limit foreign trade and exchange rate transactions through custom tariffs, quotas, and limiting foreign exchange transactions. The aim in this case is to narrow import volume and to prevent capital outflows. However, this strategy even does not stop deficits but put a pressure on these deficits. And this type of strategies is against liberalization trends and policies in a globalized world. And it is against the policies of World Trade Organization (WTO) and IMF. So there are some other alternatives repairing policies to be applied during BOP Imbalances: 1.2.1 Exchange Rate Adjustments and Elasticity Approach Exchange rate determination takes place through supply and demand forces of free markets in floating exchange rate systems. There is little or no government intervention in markets to rule the rates. When there is a deficit in BOP, then excess supply of domestic currency will appear in the markets and exchange rates will tend to increase (domestic currencies depreciate). Then foreign goods and services will be more expensive and import volume will tend to decrease. And exports will tend to increase since domestic production will be cheaper in foreign markets. And foreign exchange receipts will increase. This mechanism will work until there is equilibrium in the market. In case of a surplus in BOP, then the mechanism will work in reverse direction. This mechanism is most commonly related with current account balance of BOP. There is no application with pure floating system in real life in which there is no government intervention. So some countries have adopted fixed exchange rate system and/or fixed and free floating system combinely in which they peg their currencies to a single foreign currency or a basket of foreign currencies (SDR or others). Since the governments of these countries allow a limited floating around other currencies, this system is commonly known as “managed float system” (like in Turkey). Again exchange rate adjustment is one of the important tools to be applied by those countries. When there is a deficit in BOP, the monetary authorities will tend to devalue their currency against foreign currencies. Consequently, exports will tend to increase and imports will tend to decrease in those countries. Elasticity Approach BOP effects of exchange rate fluctuations are generally explained by Elasticity Approach. When there is a devaluation (in fixed rate systems) or depreciation (in floating rate systems) in domestic currency, then exports are likely to increase and imports are likely to decrease. The positive effects of devaluation depends on price elasticity of export demand. The higher the price elasticity of foreign demand for exports and domestic demand for imports, the more the effects of devaluation will be. This theoretical relationship was previously explained by Marshall-Lerner by the following formula: Ex + Em 1 Where Ex represents the foreign demand elasticity for exported goods/services and Em represents domestic demand elasticity for imported goods/services. According to this approach, in the case of lower elasticities for exported and imported goods/services devaluation will not be effective. It may even affect BOP negatively. However, the new studies have shown that these elasticity coefficients are enough high to have the positive effects of devaluation. 3.2 National Income Approach National income balance can be represented by the following Keynesian equation: Y = C + I + G + (X – M) So when there is an increase in consumption (C), investment (I), government expenditures (G) and net exports (exports – imports), national income will increase. Governments usually consider I and G at national level and as a national policy to affect national income. Another important assumption of the Keynesian theory is that M depends on Y. When Y increases, M will also increase. This positive relationship between Y and M is named as import function: M = m (Y) where m is marginal propensity to import. The first policy to be adopted is related with fiscal policy. For example, when there is a deficit in BOP, by fiscal policy, government will tend to reduce the expenditure side of the equation, taxes will tend to increase, and Y will decrease so that M will also decrease. Consequently, net exports will also be decreasing. The second type of policy to be adopted is related with monetary policy. In case of a deficit in BOP, government will apply a restrictive monetary policy to reduce money supply and increase interest rates so to reduce I, Y and M. However, monetary policy is commonly related with not trade balance of BOP but with capital account balance of BOP. An important disadvantage of restrictive fiscal and monetary policies is unemployment problem. When Y decreases, this will speed up unemployment. 3.3 Foreign Trade Balance and Total Consumption (Absorption) Approach Absorption approach is adopted version of national income model into foreign economic relationships. The most important contribution of this approach is that of explaining foreign trade according to the general working of the economy. When there is a deficit in BOP, then total expenditures of the country exceeds its production capacity according to this approach, meaning it produces less than it consumes. Y = C + I + G + (X-M) We can re-write the above equation as below: Y = A + (X-M) where A means total domestic expenditures and Y–A=X–M So, if Y > A, then total domestic production will be greater than total domestic expenditures and this excess production will be exported to outside and will be a surplus in foreign trade balance. If Y < A, then there will be a deficit in foreign trade balance. As a result, if Y increases, the difference between Y and A will be decreased and foreign trade balance will be obtained. On the other hand, when economy is underemployed and Y rises, A will also be rising but if Y > A (and MPS is positive), then devaluation will be beneficial. When economy is fully employed, then devaluation will not be beneficial, there is no idle capacity in the economy and excess demand will be partially met by import and prices will tend to increase. If devaluation is applied in a full employed economy, inflation will further rise. 3.4 Monetary Approach For Foreign Balance Elasticity and absorption approaches consider only foreign trade in foreign balancing disregarding capital movements. There have been important developments in financial markets and international capital movements in our new world. In order to consider the effects of capital movements on foreign balancing, monetary approach has been developed in 1970s. Monetary approach relates deficits/surpluses in BOP into monetary imbalances. Monetary imbalances occur because of the differences in the money to be kept by public and money supplied by central bank. If money supply is greater than demand for money, public will use this excess in domestic and foreign expenditures. But if money supply is less than the demand for money, then this deficit will be compensated by foreign monetary flows. Among the critical assumptions of the theory is that demand for money in every economy is the real demand derived by some factors. One of these factors is the income level of people. There is a direct relationship between real income and real demand for money. The second type of factor is that demand for money depends on interest rates among which there is an indirect relationship. Because when interest rates increase, savings will increase and this will reduce the demand for money. Real Demand for money: Md / P So the relationship between the demand for money and income and interest rates is: Md / P = f (y, i) Although demand for money is due to the public, money supply is determined by the central bank. Money supply is: MS = A ( D + R) Where A is the money multiplier, D is the emission made by the central bank for internal economic and financial purposes, and R is the domestic currency driven to the market by the use of foreign reserves. (D+R) is the monetary base of the country. When international reserves increase, then (to prevent appreciation of domestic currency) the more domestic currency will be driven to the market. If international reserves decrease, then (to prevent depreciation), the domestic currency will be drawn from the market. In fixed exchange rate systems, this mechanism gains more importance since the central bank intervenes into the market to stabilize the economy. However, in floating rate systems, there is no need for intervention and R loses its importance. Let’s assume that D is driven to the market by the central bank at the beginning so that demand for money is still constant. What will happen? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Money supply increases Consumption and investment-savings increase Part of the investment goes to the foreign portfolios There will be an outflow in capital account of balance of payments (BOP) So, an increase in MS will damage BOP. An increase in MS will have a negative effect on trade and capital balance of BOP, there will be a deficit. In fixed rate systems, the domestic currency tends to depreciate. To prevent this, the central bank will buy domestic currency by selling foreign currency into the market, so R and by multiplier effect MS will decrease. When money supply decreases, it will not be enough to meet the demand for money. The difference, this time, will be tried to be compensated by export revenues. So foreign exchange inflows will be fasten and deficit will be compensated. 4. MANAGERIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF BOP IMBALANCES 4.1 Exchange Rate Impacts Current Account Balance + Capital Account Balance + Financial Account Balance + Reserves Balance = BOP The effect of an imbalance in BOP works differently whether the country has fixed, floating or managed exchange rates. 4.1.1 Fixed Exchange Rate Countries The government bears to assure a BOP (the sum of current, capital and financial accounts) near zero. Otherwise it will intervene in the foreign exchange market by buying or selling official foreign exchange reserves. If BOP > 0, then a surplus demand for domestic currency will occur, and exchange rate (domestic currency depreciates) and to preserve fixed rate system government will intervene and sell domestic currency (so that domestic currency will appreciate, and exports , and imports ) to bring BOP back to zero. PTL STL E PE Excess Demand P1 DTL QS1 QE QD1 QTL IF BOP < 0, excess supply of the currency will occur, the government will intervene and buy domestic currency with its reserves of foreign currencies or gold. If foreign exchange reserves , then government cannot intervene and will have to make devaluation. PTL STL P1 Excess Supply E PE DTL QD1 QE QS1 QTL 4.1.2 Floating Exchange Rate Countries The government has no responsibility to peg the foreign exchange rate. The fact that the current and capital account balance do not sum to zero will automatically alter the exchange rate in the direction necessary to obtain a BOP near zero. A country running a current account deficit, with a financial account balance of zero, will have a net BOP deficit. An excess supply of domestic currency will appear in world markets. Then domestic currency will fall in value (depreciation), BOP will move back to zero. 4.1.3 Managed Floats Countries operating with managed floats take actions to maintain their desired exchange rate values. They alter the market's valuation of a specific exchange rate rather than through intervention in the foreign exchange markets. They primarily change relative interest rates to influence the economic fundamentals of exchange rate determination. The aim is to attempt to alter the financial account balance, especially short-term portfolios, to restore an imbalance caused by deficit in current account. A country may wish to increase domestic interest rates to attract additional capital or investments from abroad. Business managers use BOP trends to make forecasting in government policies on domestic interest rates. Ex. In those countries having a deficit in current account, investors may expect interest rates to increase. 4.2 Economic Development Impacts BOP is also used for economic development analysis. A deficit or surplus is not good or bad for a country. From a national income viewpoint, When a deficit occurs in current account then bad effect on GDP and employment if underemployment exists, whereas a surplus have a positive effect. When deficit GDP , emp , unemp. When surplus GDP, emp. , unemp. Under full employment, a current account deficit that can be financed by abroad would also allow imports of investment goods to . From a program viewpoint, Economic development requires net imports of goods and services which means a deficit in current account () financed by foreign savings. From a liquidity viewpoint, Deficit a country is being a net long-term creditor of the rest of the world through direct foreign investments and long term loans. Ex. Needing foreign loans to close deficits. 5. INTERNATIONAL PARITY CONDITIONS We have to describe firstly "parity conditions" in order to answer the following questions: Are changes in exchange rates predictable? How are exchange rates related to interest rates? How does inflation affect exchange rates? What is the proper exchange rate? And etc... 5.1 Parity Conditions International Monetary System (IMS) is currently characterized by a mix of freely floating, managed floating and fixed floating exchanges. No single theory is available to forecast exchange rates under all conditions. Parity conditions are certain basic economic relationships, which help to explain exchange rate movements. Parity conditions are very important out of the consideration of the reasons behind exchange rate movements. Parity conditions well explain the relations among exchange rate movements, inflation, and interest rates. So in order to make a forecast about future rates, we have to understand parity conditions better. 5.2 Prices and Exchange Rates If the identical product or service can be sold in two different markets, and no restrictions (tariffs) exist on the sale or transportation costs, the product's price should be the same in both markets. This concept is called the law of one price. A primary principle of competitive markets ==> to equalize prices across markets if no restrictions on the sales and costs If two markets are two different countries, the product's price may be stated in different currency terms, but the price of the product should remain the same. Ex. P¥ = P$ × S Where; P¥ = price of the product in Japan (Japanese Yen) P$ = price of the product in USA (US $) S = spot exchange rate And; S PY P$ if no higher price (or inflation) in one of the countries 5.3 Purchasing Power Parity and the Law of One Price PPP is an applied version of the law of one price theory, saying that any good would be priced the same in different markets or in different countries in all over the world, if there were no tariffs, restrictions on sales and costs. This theory was firstly stated by a Swedish, Gustav Cassel in 1918. He explained this theory after World War I to create the framework of new official exchange rates while returning back to Gold Standard again. When rates were imbalanced in later periods in the fixed rate system, it was used also by the central banks to create the balanced rates. We can use the same formulation of P¥ = P$ × S to find PPP between two currency. The PPP exchange rate between two currencies could be stated by: PI Y PI $ where PIY is the price index in Japan PI$ is the price index in USA in their local currencies S Ex. Identical basket of goods: S = Y1000 / $10 = Y100/$ In Japan = Y1000 In USA = $10 This is the absolute version of the theory of PPP, stating that the spot exchange rate is determined by the relative prices of similar basket of goods. PPP can be considered in two forms: 1. Absolute PPP States that spot exchange rate is determined by the relative prices of similar baskets of goods. Like in the example above. Py = S . P$ 2. Relative PPP More general idea than absolute PPP Exchange rates between two currencies will change so that it will reflect inflationary effects. So PPP regards inflationary effects. We can formulate this theory as: E1 E0 Pd Pf E0 where; E0 = exchange rate in the base year E1 = exchange rate after the base year Pd = inflation rate in domestic country Pf = inflation rate in foreign country For example, if inflation in Turkey is 50%, and in USA 10%, then we expect TL to depreciate against $ by 40% to equlalize the price of any good in both countries. Relating exchange rate movements to rates of inflation, we do not deal with the real values of E, Pd, and Pf, but deals with their percentage change. Exhibit 5.2 r in Japan is 4% lower than USA, then Yen must appreciate by 4%. US $ will be depreciated or devalued. See Halil Seyidoglu’s example …….. If r in Turkey is 30% higher than USA, $ will appreciate by 30% against TL. Point A is equilibrium point, in Point B; r in Turkey is 30% higher than r in USA, but $ appreciated only 20%. This is disequilibrium point. Empirical Tests of PPP Extensive tests have been done for the validity of PPP. Most of them did not prove PPP. PPP was not accurate in predicting future exchange rates Goods/services do not in reality move at zero cost between countries In fact, many goods are not tradable. ie. Haircuts Many goods are not the same quality across countries. Two General conclusions have been made from these tests: 1. PPP may hold up over the very long run but poorly for shorter time periods 2. Theory holds better for countries relatively with high rates of inflation and underdeveloped capital markets. But several problems exist with these tests: 1. Most of the tests used price indexes of traded goods, however there are many nontraded goods like housing and medical costs which affect traded goods and economic life. 2. It is difficult to find identical markets among countries because of taste differences, level of developments, level of incomes, etc.. PPP should be considered in identical markets. 3. PPP requires knowledge of what the market is forecasting for inflation differentials but the data that are available are either historical inflation rates or existing differential interest rates. 4. Time periods for testing have seldom been free of at least some government interference in the trade process. Because it requires no government interference to have identical market baskets. Exchange Rate Indices: Real and Nominal Exchange rate indices are used for evaluating an individual currency against other currencies to determine relative PP, whether it is “Overvalued” or “Undervalued” in terms of PPP. Nominal exchange rates are current rates in the selected period, including inflationary effects. Real exchange rates are rates calculated according to a base period, which are excluded from inflationary effects. On the other hands, nominal effective exchange rate index calculates, on a weighted average basis, the value of the subject currency at different points in time, according to trade with the country’s major trading partners. It does not indicate true value of the currency. Real effective exchange rate index indicates how the weighted average PP of the currency has change relative to selected base period. Exhibit 5.3: IMF index published frequently. Index is calculated for a base year of 1990=100 If changes in exchange rates just offset differential inflation, real effective excgange rate = 100 If exchange rates strengthen more than differential inflation, then index >100 and subject currency would be considered “Overvalued”. Index < 100, then Undervalued. A country’s real effective exchange rate index is an important tool for predicting upward or downward pressure on its BOP and exchange rate. Exchange Rate Pass – Through Incomplete exchange rate pass-through is one reason that a country’s real effective exchange rate index can deviate for lengthy periods from its PPP equilibrium level of 100. The degree to which the prices of imported and exported goods change as a result of exchange rate changes is termed Pass – Through, which is the measure of response of imported and exported product prices to exchange rate changes. Example: Assume that BMW produces automobile in Germany; when exporting the auto to USA, the price of BMW in USA should be; $ DM PBMW PBMW 1 S If DM appreciates 10% against $, P$BMW proportionally is expected to increase 10%. If it increases by the same %, then exchange rate pass-through is said to be Complete (100%). However, if P$BMW rises by less than % in S, then the pass-through is Partial. Assume: PDMBMW = DM59,500 S1 = DM1.70/$ P$BMW = $35,000 If DM appreciate 20%, S2 = DM1.4167/$, then P$BMW theoretically should be $41,999 (DM59,500 DM1.4167). But P$BMW is only $40,000. Then the degree of Pass-Through is only partial. P$BMW rose only 14.29% while SDM/$ decreased by 20%. Degree of pass through = 14.29% 20.00% = 0.71 = 71% The remaining 5.71% (20.00 – 14.29) of the exchange rate change has been absorbed by BMW. The concept of price elasticity of demand is useful when determining the desired level of Pass Through. EP % inQD % in P When BMW is Price Inelastic, meaning that QdBMW is relatively unresponsive to Price Changes, may often demonstrate a high degree of pass-thorugh. When P , then little effect on Q, so TR will . When BMW is Price Elastic, then effects will be on opposite direction. If S DM/$ and P$DM increase by 10%, then US consumers would reduce the number of BMWs purchased so TR will . Interest Rates And Exchange Rates Considering how interest rates are linked to exchange rates!! The Fisher Effect Named after Irving Fisher, stating that nominal interest rates in each country are equal to the required rate of return plus compensation for expected inflation. i=r+ where; i = nominal interest rates, r = real interest rates, = expected rate of inflation Forecasting future is difficult because of . Empirical tests have shown that Fisher Effect exists for short maturity government securities like treasury bills and notes. In LR, there are fluctuations and financial risk. International Fisher Effect It sets relation between % in S and differential interest rates. S1 S 2 100 i$ i S2 Fisher open states that % in spot rates should be equal to interest rate differentials. Example: $ based investor buys a 10-year Yen bond earning 4%, compared with 6% interest available on $. Investor expects Yen to appreciate against $ by at least 2% per year during 10 years. If not, $ based investor will be better off. If Yen appreciates by 3% during 10 years, $ based investor would earn 1% higher return of bonus. Interest Rate Parity (IRP) IRP provides a linkage between foreign exchange markets and international money markets. IRP is in the result of arbitrage possibilities among international money and foreign exchange markets. Funds will move from low rate countries to higher rate countries. When borrowing, investors prefer lower interest rates, when investing, they prefer higher rates of interest. Example: Assume an investor has $1,000,000 to invest and two alternatives to follow: 1. $ based investment on securities 2. SF based investment on securities They have identical risk and maturity. Parity condition for these alternatives; 1 i$ S SF / $ 1 i SF 1 F SF / $ = 1 0.02 1.4800 1 0.01 1 1.4655 Ignoring transaction costs, if both sides are equal to each other, S and F rates are considered to be at IRP. Any difference in interest rates must be offset by the difference between S and F. F 1 iSF SF1.4655 / $ 1.01 0.99 1.00 1 i$ SF1.4800 / $ 1.02 S In order to avoid risk, forward rates are agreed today. There is no profit among $ and SF investments. We can simplify the above formula as; i$ iSF F S S When i$ iSF Example: F S S , then funds will move from USA to Switzerland, otherwise to USA. i$ = 10% 0.70 0.10 iTL = 70% S = 1$: 430,000 TL F 430 ,000 430 ,000 F = 1$: 688,000 TL If F = 1$: 550,000 TL, then; 0.70 0.10 550 ,000 430 ,000 0.60 0.28 430 ,000 This time, funds will move from USA to Turkey. There will be arbitraging profit called Covered Interest Arbitrage (CIA). For example, 1. Purchase of Yen in the spot market and sale of Yen in the forward market narrows the premium on the forward Yen. The spot yen strengthens from the extra demand and the forward Yen weakens because of extra sales. A narrower premium on the forward Yen reduces the foreign exchange gains previously captured by investing in Yen. 2. The demand for Yen denominated securities causes Yen interest rates to fall, while the higher level of borrowing in the US causes $ interest rates to rise. The net result is a wider interest differential in favor of investing in the $. CIA continues until IRP is established again. Example: P.125, Exhibit 3.9, 3.10 and 3.11 (Eiteman, 2001) Profit on $: $1,040,000 i$ i Profit on Yen: $1,044,638 FS 106.0 - 103.5 8% - 4% 4% 2.4% F 103 .5 Funds will flow from USA ($) toward Japan (Yen) until IRP is established. The net result of the disequilibrium is that fund flows will narrow the gap in interest rates and/or decrease the premium on the forward Yen. The interest rate parity line (p.126) shows the equilibrium state, but transaction costs cause the line to be a band rather than a thin line. Transaction costs arise from foreign exchange and investment brokerage costs on buying and selling securities. Typical transaction costs in recent years have been in the range of 0.18% to 0.25% on an annual basis. Point X shows one possible equilibrium position where a –4% interest differential on Yen securities would be offset by a 4% premium on the forward Yen. Point U is the disequilibrium position where Yen premium is 4.83%. Y 106.00 / $ Y 103.50 / $ 360 days 100 4.83% Y 103.50 / $ 180 days Calculation of Forward Rates at IRP: n 1 iY 360 Fn Y / $ n 1 i$ 360