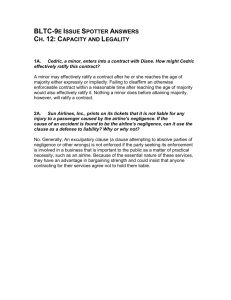

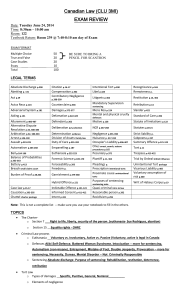

Torts Briefs

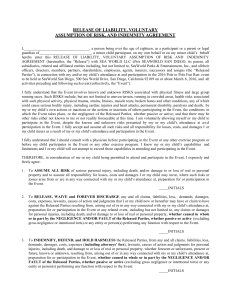

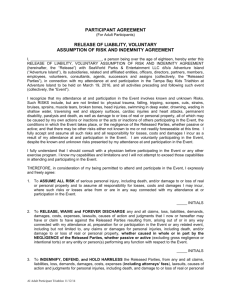

advertisement