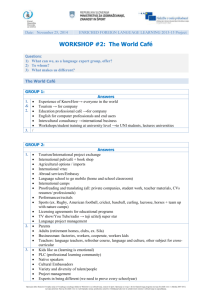

Lost in translation: using a translation model of science

advertisement

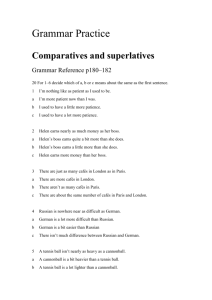

Science cafés in cultural settings: A translation model and a case study from Denmark Kristian H. Nielsen and Gert Balling, Videnskabscaféen* 1. Introduction There is a growing interest in the scope and meaning of public communication of science and technology across political and national cultures. Science and technology studies (STS) have long emphasized the need to rephrase in terms of human values, social practices and entangled networks the a-historical and a-cultural perception of science, which depicts science as nothing but universal method and pure rationality. Similarly, scholars and practitioners of public understanding of science and science communication are beginning to recognize the crucial importance of social and cultural contexts of public communication of science. In themed sections and individual articles on science communication outside the dominant contexts of the US, UK and other drivers within science literacy and public understanding of science, many authors have analyzed developments in Latin America, the Mediterranean countries, Denmark, Japan, India, China, etc. (Castelfranchi, 2004; Evangelista & Kanashiro, 2004; Greco, 2004; Higashijima, Takahashi, & Kato, 2009; Mazzonetto, 2005; Nielsen, 2005; Pitrelli, 2005). In this paper, we too would like to stress the urgency and explore the wider implications of this conclusion. Too long, we believe, have public understanding of science scholars and practitioners concerned themselves with the deficit model as if this model was universal, thus failing to recognize the cultural limitations of their concern due to the fact that the deficit model is embedded in US and UK discourses about science literary and public understanding of science (Sturgis & Allum, 2004). In a partly ironic spin on the importance attached to criticizing the deficit model in Anglophone contexts, science writer David Dickson made a case for a renewed deficit model in the developing countries. In effect, he argued that in breaking with the “old” deficit model scholars and practitioners have forgotten that “providing reliable information in an accessible way--in other words, filling the relevant ‘knowledge deficit’--is an essential prerequisite of both healthy dialogue and effective decision-making” (Dickson, 2005). Replacing the deficit model with more sophisticated and democratically adequate models based on dialogue, participation, and engagement has surely widened the analytical scope of public communication of science and technology (Trench, 2008). However, as long as different structural, historic, and cultural contexts of such models are not fully addressed we are still left with a fairly narrow view of communicative processes involving issues pertaining to science and technology. We urge that the move towards analytical models of science communication needs be informed by comparative cases across cultures. In this paper, we present an analytical framework for addressing the cultural contexts of science communication in the form of a translation model of science communication. Using the concept of translation drawn from actor-network-theory, we argue that science communication may be seen as a three-fold process of translation. The first translation involves the transformation of events and ideas from science and society into media and venues of science communication. The first translation process enables a second translation in which the meaning of science and scientific knowledge may be interpreted by new actors; for example, the participants of science cafés. Thirdly, there is translation of particular science communication concepts, such as science cafés, across national and regional borders. We argue that in order to fully acknowledge cultural settings of science communication, it is useful to be able to include all three levels within one and the same theoretical framework. * www.vcaf.dk 1 Secondly, our paper addresses the emergence and spread of science cafés across cultural settings. The authors of this paper have been actively engaged in the science cafés movement. Science cafés, today, form a worldwide network of local organizers in a great variety of cultural settings, and we make no attempt to present the full story of what science cafés are all about. We aim to make useful our theoretical framework in presenting our stories about the translation processes involved in the setting up and running of science cafés in Denmark. We want to provide a first exploration of whether it makes sense to think about science communication as processes of translation. The guiding question in recalling our own experiences in starting up and operating science cafés is: How can we understand the emergence and practice of science cafés in Denmark in terms of a three-fold translation model of science communication? 2. The translation model of science communication In Science in Action, Bruno Latour (1987) introduced the notion of translation to make sense of two, incomparable perceptions of science. On the one hand, we think about scientific research in terms of construction, communication, and controversy. This is what Latour called science-in-the-making. On the other hand, we also conceive of science as an established body of facts. This is the kind of readymade science that we typically find in textbooks. The concept of translation designates all the minute steps in which hypothetical statements, scientific discussions, and experimental settings are gradually being transported and transformed from science-in-the-making to readymade science. In order to connect these two, seemingly incompatible “faces” of science, Latour (1987) contrasted the model of translation with that of diffusion (p. 132-144). The model of diffusion states that scientific knowledge moves freely from one place to another, say from science to the general public. Facts and objects are invariable, and, so, there should be an easy and direct diffusion of knowledge from science-in-the-making to readymade science. Traditionally, the diffusionist view has been widely accepted as a model of public communication of science and engineering. It covers a broad range of different notions such as the deficit model and the communication model of dissemination (Bucchi, 2008; Trench, 2008). The diffusion model introduces an asymmetry between, on the one hand, scientific aspects defining truth and facts, and, on the other, social factors appealed to only in order to explain the distortion of the true path of reason. In contrast, the model of translation asserts that social, rational, and technical factors should be treated on the same level of analysis. The translation concept invites the notion of continuous transformation of all elements that facilitate movements from science-in-the-making to readymade science. In processes of translation, such as those involved in communicating scientific knowledge to non-scientific audiences, facts about nature are embedded in new social contexts and thus take on new, additional meanings. Drawing on Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe (2009), we see science communication as consisting of three, interrelated processes of translation, see figure 1 and 2. The first translation, translation1, happens when specific events and topics become the center of attention in specific forums of science communication: for example, when the media takes an interest in particular aspects of science, or when organizers invite speakers for a science café event. We want to stress that this first translation process adds new social contexts to the meaning of scientific knowledge. Becoming a topic of science communication, scientific knowledge is translated from one social context to another and, in the process, takes on additional meanings. Whereas, to begin with, the knowledge in question is “purely” scientific in the sense that only scientists really thought about it and wanted to make use of it, as soon as it is being communicated to non-scientists in some form or another it takes on what we would call additional socio-scientific meanings. Translation2 takes place within forums or media of science communication. This is where scientific knowledge becomes more thoroughly embedded in larger social contexts. Most media of 2 science communication operate in very context-specific ways and involve very different types of social actors. Clearly, whether we are talking about highly commercial and professional mass media, or more grassroots-like activities such as science cafés, or strategic efforts aimed at public participation in science or public understanding of science, makes a huge difference to the translation process. However, even such dissimilar and unrelated forums of science communication have one thing in common. In translating pertinent aspects of science into public communication, all media or forums of science communication enable the production of new social contexts for scientific knowledge and, in so doing, bring into being science as a “matter of common concern” (Latour, 2004). Translation3 occurs when certain modes of science communication have become stable enough to become transferred from one social or cultural context to another. Of course, most instances of science communication arise in the context of already established media of communication. In such cases, the third translation process is not unique to public communication of science. The mass media have undergone and are undergoing processes of global translation, which have nothing to do with communicating science--although the consequences of such transformative developments have great influence on the specific ways in which science is actually being communicated, i.e., the translation1 and translation2 processes. Other translation3 processes, such as the proliferation of science cafés across the globe, are highly specific to science communication. In the following we want to make use of this translation model of science communication to reflect upon our own experiences with introducing and running science cafés in Denmark. First, we will make a small detour tracing the making of the international science café movement and describing the prevailing modes of science cafés. 3. The making of an international science café movement The first UK science café known as the Café Scientifique took place in a wine bar in Leeds in 1998. Conceived by Duncan Dallas, who used to make TV programs on science, the event was inspired by the French Café Philosophiques where people turn up in cafés to discuss philosophical issues. The event was advertised as “an evening where, for the price of a cup of coffee or a glass of wine, anyone can come to discuss the scientific ideas and developments which are changing our lives”. Much to the surprise of the organizer, a speaker on Richard Dawkins’ idea of The Selfish Gene drew a crowd of 40-50 people (Dallas, 1999, 2006). Since then, backed by funding from the Wellcome Trust which enabled the appointment of an organizer to travel the country and assist people in setting up cafés in their own town or city, the Cafés Scientifiques have spread across the UK with more than fifty or so local initiatives up and running. The UK Café Scientifiques have their own website (www.caféscientifique.org.uk), and there are a number of Junior Café Scientifiques, or Café Scientifiques in schools (www.juniorcafésci.org.uk). Basically, the UK format includes an invited speaker--usually a scientist or science writer, a venue--a café-bar with a side room, and a topic that has a scientific basis, but also social relevance. The invited speaker talks for about 20 minutes or so without any visual aids; then, there is a break for drinks followed by questions and discussion for about an hour or so. The audience basically is anyone interested. Information about the event is distributed by email and possibly posters and flyers in a local library, in the venue itself and in other places. Importantly, all the Cafés are run locally (Dallas, 2006). Around the same time in France, other science cafés were appearing. In the summer of 1997, the Société Française de Physique organized a public “Bar des Sciences” as part of their annual conference, held in Paris, July 7-10. Later that same year, in Lyon, science journalist Nathaly Mermet and members of the Sciences et Citoyens (Sciences and Citizens) club at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (National Center for Scientific Research) began their regular 3 series of science cafés. (The Lyon group also organized the first Junior Cafés.) The French format, known as the Café des Sciences or Bar des Sciences, differs from the British Café Scientifiques. There is an “animateur” (host or moderator) introducing the topic of the event, which is usually identified by the local organizing committee. The animateur also directs and inspires the debate. There is a panel of “intervenants” (introductory speakers), usually three to five persons, rather than just one scientist. The panel is selected with a view to balancing of opinions and expertise. Typically there is one or two scientists (representing different fields of expertise), a representative of some form of counter-expertise, for example NGO’s or other citizens’ groups, and a politician. Each panelist is allotted but a brief time for presentation before the general discussion sets off. The French model includes two important elements: the debate primarily takes as its point of departure the questions of the audience, and different voices of opinion, expert as well as non-expert, will have to be expressed. Both elements serve to increase the interaction between the introductory speakers and their audience. In 2001, inspired by the French and British initiatives, Gert Balling and Emmanuelle Schuler initiated the Copenhagen School of science cafés (Balling & Schuler, 2004). They adopted the idea of a moderator and a heterogeneous panel from the French cafés, adding the twist that the topics of the Copenhagen cafés were defined not so much because of their scientific basis, but rather because they appealed to people from many different spheres of life: artists, scientists, engineers, journalists, politicians, etc. Balling and Schuler explicitly wanted to establish a forum outside the traditional channels of science communication and outside the professional circles of expert discussion, a forum in which reflective dialogue and social implications of science and technology are on the agenda. Moreover, they expanded the concept of the science café to include a preparatory dinner with the moderator and the invited introductory speakers in order to set the dialogue in motion before the actual event. One important ambition of the Copenhagen School is to engage dialogue amongst the invited speakers. Science cafés have emerged in many different countries such as Poland, USA, Japan, Italy, the Netherlands, Brazil, and several African countries. The spread of the British Café Scientifique model was partly enabled by support of the British Council. In 2004, the Council took an interest in the concept and, according to their homepage, has been running Café Scientifiques in more than 40 countries from Australia to Brazil, Egypt, and Turkey. Other than the British Council the Wellcome Trust has also supported the internationalization of the science café movement. For example, an International Engagement Award from The Wellcome Trust has enabled the establishment of a science café in Uganda, and the trust also sponsored the Café Scientifique Organizers’ Conference, March 12-13, 2007, in Leeds (Grand, 2007). To sum up, there are many different ways of translating science and technology in science cafés. At the Leeds conference, Duncan Dallas observed that in the UK a variety of new set-ups was being engaged: comedy cafés, cafés in art and photography galleries, and play readings. Probably, the same development is taking place in many other countries. This is highly interesting as new initiatives clearly demonstrate ongoing translation3 processes involving the science café format. Even though the science café movement already has its own “creation accounts”, such accounts in no way define what science cafés are all about. In other words, the public engagement in science ideas embodied in UK, French, or Danish style science cafés far from encapsulates what actually is going on in science cafés all around the world. People seem to be engaging with science in science cafés (translation1 and 2) in many different ways because of the translation3 of the science café format. So far, in our description we have emphasized three stable modes of doing science cafés. We do not want to give the impression that all science cafés fall nicely into such categories, far from it. In the following, based on our own experiences we will discuss the translation1+2+3 of science cafés in Denmark. 4 4. Translations of the Copenhagen School of science cafés Today, the Copenhagen format of science cafés is used in Copenhagen and in Aarhus as a communicative framework of somewhere between 5 and 15 science cafés a year. Each science café starts out with the identification of a cross-disciplinary theme of perceived public interest. This is where the translation1 of science and technology takes place. Quite often, topics that have news value, i.e. topics that are being discussed in the mass media, are selected, but not always. If the topic is already in the public eye, then we might say that to some extent the translation1 process has already taken place. However, there always remain the specific matters of translation1, which consists in getting particular people with particular types of expertise to contribute to the café in a particular location. When this has been accomplished, there also remains the question of facilitating the translation2 process. Let us take two examples, one from Aarhus and one from Copenhagen, to show how the processes of translation1+2 work in practice. Our first example is a science café on assisted reproduction held on October 12, 2007 in Aarhus. The second example is a series of science cafés on biotechnology and cloning held in Copenhagen from 2002 to 2010. The translation1+2 of assisted reproduction The science café on assisted reproduction in Aarhus was organized in collaboration with the Steno Museum, the Danish Museum for the History of Science and Technology. In October 2007, the museum featured a show on assisted reproduction called “Ovulation: Having babies with technology”. There was a legitimate concern on behalf of the museum to communicate this show to a wider public, but the choice of topic also reflected a more general public concern about the development of assisted reproduction. For example, since 1995 the Danish Council of Ethics, which provides advice to the Danish Parliament and raises public debate ethical issues in the field of biomedicine, has published extensively on assisted reproduction. In an extensive report from 2004, the council treats many different technologies and many different ethical aspects of assisted reproduction (Danish Council of Ethics, 2004). In 2005, controversially, the council recommended the legalization of insemination of singles and lesbians. To a large extent, the science café on assisted reproduction fed on existing public discussions. In a way, the translation1 of the technology of assisted reproduction into a matter of common concern had already been accomplished. The task of the science café organizers was simply to enact this translation1 process in the actual science café. However, since the Copenhagen School only allows three or four persons as introductory speakers, the organizers needed to simplify the existing public translations1 of assisted reproduction. Also, of course, there are more practical concerns involved in the selection of a suited panel such as: Who is available? Who is a good speaker? Will the panel presenters be able to enter into a constructive dialogue with each and with the audience? Based on such considerations, it was decided to invite a fertility physician who runs his own fertility clinic, a philosopher specializing in bioethics, and an infertility researcher. Other panelists were considered such as representatives of the Organization of Involuntarily Childless Couples, health politicians, and priests. For various practical reasons, these people were either not invited or invited and could not come. Although this is a common and somewhat trivial condition for all public dialogue events such as this one, we think there is a more general conclusion to be drawn about the process of translation1 of science and technology. Translating scientific information about fertility and technologies of assisted reproduction into socio-scientific issues, the organizers had to draw on many different resources. They consulted scientific, technological, and ethical expertise, but also used their own knowledge based on the ongoing public debate about assisted reproduction. There 5 seems to be no general solution to the problem of constructing social, ethical, and legal aspects of science and technology. It has to be solved locally in translation1+2 processes. As it happened, the science café on assisted reproduction was no ordinary science café. The organizers came up with the idea of using the planetarium of the museum as the location of the event. It was decided to have the science café with the lights turned down to an absolute minimum and with the (artificial) starlit sky above. The rationale behind this idea was that with the lights almost off, the spoken words would stand out even more clearly. The decision to have the science café in the dark, so to speak, clearly made an impact on the translation2 processes taking place in the actual science café. First of all, the role of the moderator was slightly changed. More time and energy was spent on figuring out the speaking order, even though this did not present as big a problem as the organizers had originally feared. The darkness made the moderator more visible as many people relied on the moderator to sort out the debate in terms of who was saying what, and so on. Secondly, the dark room also seemed to have an effect on the difference between experts and audience. In theory, it was impossible to see who was speaking, although in practice all people present seemed to be aware of the spatial location of different voices, including those of the experts. Still, sometimes people would speak all at once which meant that the authority of the experts’ statements was slightly blurred. The organizers felt that the darkened ambience of the planetarium did result in a more equal and thus more democratic debate. We have no way of validating this claim. We just observe that the actual setting of the event, including physical and social features, did seem to influence the process of translating2 science and technology into matters of common concern. The translation1+2 of biotechnology (cloning) The most popular theme for science cafés held in Copenhagen has turned out to be biotechnology and, more specifically, cloning. We have had regular cafés on issues pertaining to biotechnology since the café got started in 2001, and they have always been well visited. Most of our biotech science cafés have been located at the KafCafé, a theater café in the middle of the old city of Copenhagen. A bar with a small stage, old theater posters at the walls, and laid back atmosphere are all characteristic features of the venue. The maximum capacity is 110 people in the room, but, according to our experience, the science cafés work well with an audience around 60 persons. As it happens, this is the crowd we usually attract in the Copenhagen science cafés. Needless to say, the Copenhagen science café did not invent biotechnology or cloning as public matters of common concern. Cloning has been on the public agenda in Denmark at least since 1997, when Scottish scientists made an announcement that they had successfully cloned Dolly, a Finn Dorset sheep, from an adult cell. As in many other countries, the Danish cloning debate has revolved around biomedical applications and applications relating to agriculture and food production, with the former commanding a certain degree of acceptance compared to the latter (Gamborg et al., 2006). With respect to human cloning, the debate concerned issues such as reproductive and therapeutic applications. In 2001, the Danish Council of Ethics (2001) published a report in which reproductive cloning of humans, aimed at creating a genetic copy of an existing human being, was sharply condemned, whereas the idea of cloning embryonic stem cells in order to advance genetic therapies was received with some ambiguity. The report recommended doing research on embryonic stem cells only with leftover embryos from in vitro fertilization, since therapeutic uses of stem cells still was considered to be highly speculative. As was the case with the Aarhus science café on assisted reproduction, the Copenhagen cafés on biotechnology and cloning all have been more or less directly related to ongoing public debates, but also reflect the ways in which the organizers have chosen to make such general debates viable 6 as a topic for informal dialogue and debate about scientific and technological issues. The process of translating1 matters of common concern into specific science cafés more often than not combines available media framings with the personal interests of the organizers and the social setting of the event. The first Copenhagen science café on cloning, held on March 18, 2002, was conceived as a general introduction to the technical and ethical aspects of cloning. The introductory speakers were one of the leading researchers on animal cloning in Denmark and an ethicist-philosopher. Juxtaposing expert knowledge on cloning as a technology and on the social and human relevance of cloning, this café very clearly expressed the general philosophy of the organizers (see also below on the so-called manifesto of the Copenhagen science cafés): To enhance public awareness of science and its social and human consequences, but also to facilitate dialogue across scientific borders. In all, in the period 2001-2010 seventeen science cafés in Copenhagen have been organized, all of which have dealt with scientific, technical, ethical, and social aspects of cloning and biotechnology. Involving the audience in the debate is the most important goal of the Copenhagen science cafés. Even though the introductory speakers are privileged in being able to set agenda by picking out central questions, in the pursuing debate the audience is allowed much freedom in terms of raising questions and topics for discussion. The role of the moderator is to take into account the interests of the audience. Our experience is that both introductory speakers and people in the audience are keen on discussing the relationship between cloning and the idea of what is natural. Is cloning unnatural? What happens if we move the boundaries between the man-made and the natural? Is the man-made sufficient? The translation3 of the Copenhagen School The Copenhagen School of science cafés has emerged in the context of the Danish culture of “consensus” (Horst & Irwin, 2010). Well-know public engagement activities such as the Danishstyle consensus conferences with a lay citizen panel in dialogue with expert panels have resulted from the consensual approach that combines expert knowledge with public education/participation, striving for the inclusion of potentially all members of society in political issues and expert decision-making. Consensus conferences have been described variously as a way in which to perform “technology assessment” and as particular mode of “democratizing expertise”, with the latter concept drawing attention to the disclosing of expert dissent (Blok, 2007; Joss, 1998). Experiences from implementing the Danish consensus conference in European, American, and East Asian countries suggest “that the consensus conference model is one that ‘travels well’ and is easily adapted to contexts outside Europe” (Einsiedel, Jelsoe, & Breck, 2001, p. 91; see also: Goven, 2003; Guston, 1999; Seifert, 2006). The initiators of the Copenhagen School have tried to promote their ideas internationally. In European conferences for science café organizers such as the 2007 conference in Leeds (mentioned above), and on a couple of visits to Japan, lectures have been given, including examples of what it means to have a science café “the Copenhagen way”. In 2007, the Copenhagen science café was nominated for the EU Descartes Prize for excellence in science communication. The nomination ran as follows: The Science Café is just the right place to help scientists and members of the public to meet and mingle and to launch lively discussions targeting current issues in scientific research. What is especially advantageous is that the Café is informal, thus providing comfortable surroundings for the public. […] The bottom is that both the scientific community and the public benefit from this venture. The Cafés imparts scientific knowledge to people active in the fields of art and culture, while it also contributes to further integrating societal, cultural and artistic issues into scientific practice (European Commission, 2007, p. 34). 7 Clearly, the ideas behind the Copenhagen School of science cafés were easily translated into the nomination and, thus, promoted to a wider European audience. However, the translation3 to other contexts has only proved partly successful. The Copenhagen School of science cafés has succeeded in becoming a national ‘brand’ with regular science cafés in Copenhagen and in Aarhus, and with a high degree of visibility within the Ministry of Science and in the scientific community. However, we have no knowledge about specific initiatives in other countries besides Denmark where the Copenhagen School of science cafés has become a permanent feature. The experiences of organizing science cafés in other cultural settings may provide some background for understanding this particular feature of translation3, which indicates that general ideas about science communication spread relatively easy, whereas practices and routines are somewhat more difficult to translate3 from one national context to another. 6. Conclusion The science café movement has gone global, having become a regular part of the science communication “landscape” in many countries. In order to understand the transportation and the transformation of the science café format, we propose a three-fold translation model of science communication. Translation, in this context, refers to the movement and interpretation of ideas about science, science communication, and public concerns. The first translation happens when science café organizers pick up on a scientific and/or social topic, turning it into a science café event. They are relatively free to choose among several formats of science cafés (even to come up with a format of their own), and they have the opportunity to frame the topic according to their own interests and/or their perception of what their intended audience might find interesting. The translation1 involves an open-ended interpretation of topics, formats, speakers, and audiences that are deemed appropriate for a particular instantiation of science cafés. We have provided a few examples from the Danish context of how translations1 may occur. The second translation takes place in the context of the actual science café. This, too, is a more or less open process in which the original ideas of the organizers and the presentations of the speakers are being negotiated by the audience, the speaker(s), and the moderator. Some science cafés are quite similar to the traditional science lecture, where the speaker more or less is able to set the agenda, if only because he/she is allotted most speaking time and/or the national culture of debate puts a limit to the kinds of questions being asked. Other science cafés, for example Danishstyle science cafés, attempt to enable critical and cross-disciplinary debate/dialogue. Translation2, then, builds on translation1, but also adds many new and unintended perspectives to the initial translation1. Translation3 relates to the cultural context of science cafés. Translation3 comes about when particular formats of science communication are exported from one socio-cultural setting to another. For example, when the British Café Scientifique format is adopted to an African or Asian context, or when Danish-style science cafés are being attempted in other countries. Again, the process, in principle at least, is open and transformative. The Danish science cafés emerged as a composite of the British and French models, whereas the evolution of science cafés in other cultural settings have shown that cultural adaptation can proceed along with cross-cultural fertilization. References Balling, G., & Schuler, E. (2004). The science café: science, art and culture. Højbjerg: Hovedland. Blok, A. (2007). Experts on public trial: on democratizing expertise through a Danish consensus conference. Public Understanding of Science, 16(2), 163-182. 8 Bucchi, M. (2008). Of Deficits, Deviations and Dialogues. In M. Bucchi & B. Trench (Eds.), Handbook of public communication of science and technology (pp. 57-76). London and New York: Routledge. Callon, M., Lacoumes, P., & Barthe, Y. (2009). Acting in an Uncertain World: An Essay on Technical Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Castelfranchi, Y. (2004). Science Communication around the World: eyes on Brazil. Journal of Science Communication, 3(4). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/03/04/F030401/ Dallas, D. (1999). The Cafe Scientifique. Nature, 399(6732), 120-120. Dallas, D. (2006). Cafe Scientifique - Deja Vu. Cell, 126(2), 227-229. Danish Council of Ethics. (2001). Kloning - Udtalelser fra Det Etiske Råd og Det Dyreetiske Råd. Copenhagen: Danish Council of Ethics. Danish Council of Ethics. (2004). Kunstig befrugtning - etisk set. Copenhagen: Danish Council of Ethics. Dickson, D. (2005). The case for a 'deficit model' of science communication. SciDev.net, (27 June). Retrieved from http://www.scidev.net/en/editorials/the-case-for-a-deficit-model-of-sciencecommunic.html Einsiedel, E. F., Jelsoe, E., & Breck, T. (2001). Publics at the technology table: the consensus conference in Denmark, Canada, and Australia. Public Understanding of Science, 10(1), 8398. European Commission. (2007). Descartes communication prize: Excellence in science communication Available from http://ec.europa.eu/research/scienceawards/pdf/descartes_communication_2006_en.pdf Evangelista, R., & Kanashiro, M. M. (2004). Science, Communication and Society in Brazil, the narrative of deficit. Journal of Science Communication, 3(4). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/03/04/F030403/ Gamborg, C., Gjerris, M., Gunning, J., Hartlev, M., Meyer, G., Sandøe, P., et al. (2006). Regulating Farm Animal Cloning: Recommendations from the project Cloning in Public. Retrieved from http://www.bioethics.kvl.dk/tekster/CeBRAreport15.pdf Goven, J. (2003). Deploying the consensus conference in New Zealand: democracy and deproblematization. Public Understanding of Science, 12(4), 423-440. Grand, A. (2007). Cafe Scientifique Organisers' Conference 2007. Retrieved 8 April, 2009, from http://www.cafescientifique.org/downloads/conference%20report.pdf Greco, P. (2004). Towards a "Mediterranean model" of science communication. Journal of Science Communication, 3(3). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/03/03/F030304/ Guston, D. H. (1999). Evaluating the first US consensus conference: The impact of the citizens' panel on telecommunications and the future of democracy. Science Technology & Human Values, 24(4), 451-482. Higashijima, J., Takahashi, K., & Kato, K. (2009). Mouse model: what do Japanese life sciences researchers mean by this term? Journal of Science Communication, 8(1). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/08/01/Jcom0801%282009%29A01 Horst, M., & Irwin, A. (2010). Nations at Ease with Radical Knowledge On Consensus, Consensusing and False Consensusness. Social Studies of Science, 40(1), 105-126. Joss, S. (1998). Danish consensus conferences as a model of participatory technology assessment: an impact study of consensus conferences on Danish Parliament and Danish public debate. Science and Public Policy, 25(1), 2-22. Latour, B. (1987). Science in action. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Latour, B. (2004). Politics of nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 9 Mazzonetto, M. (2005). Science communication in India: current situation, history and future developments. Journal of Science Communication, 4(1). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/04/01/F040101/ Nielsen, K. H. (2005). Between understanding and appreciation: current science communication in Denmark. Journal of Science Communication, 4(4). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/04/04/A040402/ Pitrelli, N. (2005). The new "Chinese dream" regards science communication. Journal of Science Communication, 4(2). Retrieved from http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/04/02/F040201/ Seifert, F. (2006). Local steps in an international career: a Danish-style consensus conference in Austria. Public Understanding of Science, 15(1), 73-88. Sturgis, P., & Allum, N. (2004). Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 13(1), 55-74. Trench, B. (2008). Towards an Analytical Framework of Science Communication Models. In D. Cheng, M. Claessens, T. Gasgoigne, J. Metcalfe, B. Schiele & S. Shi (Eds.), Communicating Science in Social Contexts (pp. 119-135). Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. 10