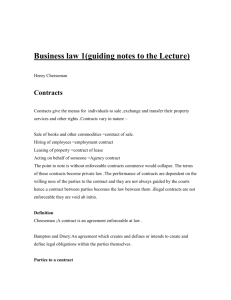

Contracts Notes

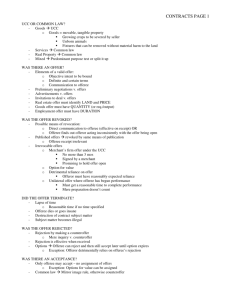

advertisement