Relational Networks and Enterprise Law

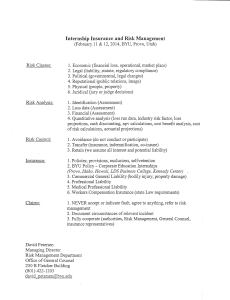

advertisement