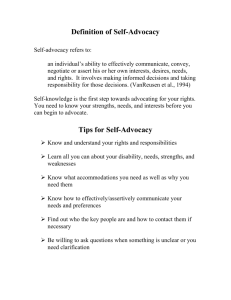

Self-Advocacy Technical Assistance Guide

advertisement