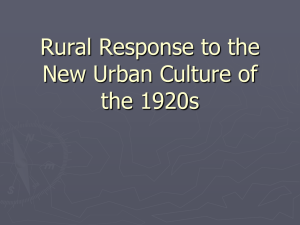

1920s US History DBQ: Old vs. New Tensions

advertisement

Christopher Smith AP US History Mrs. Norris 6th hour Sample DBQ Response to demonstrate document integration Prompt: The 1920s were a period of tension between new and changing attitudes on the one hand and traditional values and nostalgia on the other. What led to the tension between old and new AND in what ways was the tension manifested? The firestorm of the Great War revealed an American society rife with conflict and opposing values. Americans reacted to the legacy of the war with new political doctrines, contentious views of religion, and emerging social and artistic trends. Heightened tensions were demonstrated by how Americans reacted to the legacy of the Great War. Debate over religion, morality, politics, economics, and art broke along modern and traditional lines. The roaring 20s manifested these differences in court rooms, national politics, grass roots campaigns, and in the emerging transportation and media revolutions. American religion became a major front in the 1920s’ culture wars. Mainstream Protestantism, Fundamentalism, Catholicism, and Judaism were prominent and controversial. While traditional Protestants retained control of America’s commanding heights, the influx of fundamentalism among “old stock” Americans and the importation of Catholicism and Judaism with “new immigrants” created a volatile mix. New York’s Alfred Smith was unable to win the presidency in 1928 largely because of his Irish Catholic faith. Preachers such as Billy Sunday and Aimee Semple MacPherson attracted national audiences through their sophisticated use of new media outlets such as the radio. Ironically, modernism shaped the religious resurgence in the 1920s. MacPherson’s revivals were known for having “sex appeal” and being a form of “supernatural whoopee.” (Doc I) Even the fundamentalist movement was shaped by the new trends in the United States. The presidencies of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover maintained the practice of traditional Protestantism in the White House, but that did not prevent national upheaval over the brand of religion propagated by Sunday and MacPherson. The introduction of the theory of evolution into the high school curriculum awoke the sleeping giant of fundamentalist Christianity and created tension over the separation of church and state. Evolution versus creationism became a metaphor for the much larger religious debate in the United States. The Scopes Monkey trial demonstrated the religious tension of the era. Creationism was defended by the former populist presidential candidate and former secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan. Clarence Darrow defended the Science teacher, John T. Scopes. Bryan and Darrow battled for weeks over their religious interpretations and beliefs. Modernists challenged the notion that “everything in the bible should be literally interpreted.” Whereas fundamentalists believed the likes of Darrow were voicing a “slur to the bible.” (Doc C). Their debate represented a national tension over the variety of religious beliefs existing in the United States by the 1920s. Religion also served as a pseudonym to discuss America’s new ethnic diversity. In 1800 the United States was made up of African slaves, Native Americans, and a smattering of protestant northwestern Europeans. In 1921 Warren G. Harding presided over a nation of eastern European Jews, Irish, Italian, and Polish Catholics, African American Baptists, and White Anglo Saxon Protestants. The teeming masses populated America’s cities, but the governors’ mansions and Congressional seats were still firmly under the control of white Anglo Saxon males. Congress passed three immigration laws in 1921, 1924, and 1927 to cut off immigration from undesirable regions. The immigrants Sacco & Vanzetti reinforced this fear of immigrants. “100% Americans” questioned the loyalty of new immigrants to the country. Catholics were feared to obey the Pope, instead of the president. Jews were believed to carry with them the radical ideologies their Russian homeland, as exemplified in the case of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. White fears were not assuaged by political domination. The KKK’s presence served to intimidate blacks, Jews, and Catholics who strove for political representation, or even just urban integration. Lynchings occurred in almost every state in the 1920s, not just in the traditional south. The Palmer Raids of 1919 & 1920 set the standard as the zenith of xenophobic hysteria. Groups such as the KKK and the 100% Americanism movement manifested outside of the government’s mandate, demonstrating the grass roots tension in the country. The Klan unabashedly believed they represented the “old stock” Americans who had “given the world almost the whole of modern civilization.” (Doc D). Nostalgia like the Klan’s represented a yearning for the old America. The political domination of the Anglo Whites does not indicate that minority groups acquiesced to the pressures of the “old” America. African American leaders and artists represented the immediate legacy of the Great Migration. Black nationalists like Marcus Garvey represented a “new negro” pushing against subjugation. Garvey’s “black nationalism” departed from Booker T. Washington’s traditional approach to integration and even moved a step further than W.E.B. DuBois’ belief in full integration. Harlem Renaissance writers created a new style for blacks, as well as all Americans that broke from the traditional artistic patterns. Langston Hughes redefined his color by declaring “black is beautiful.” Claude McKay’s poetry embodied Garvey’s black nationalist rhetoric in works like “If We Must Die.” Perhaps the most immediate dissemination of the new black culture into old America was in music. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Bessie Smith defined the Jazz era with their pure form American music. This new art form sounded like the “eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro Soul, the tom-tom of revolt.” (Doc E). Jazz combined the old classical instrumentation and the new rhythms brought to the north by the Great Migration. African Americans were not the only new artists breaking ground. The Lost Generation of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Stein criticized America’s “return to normalcy” and demonstrated their disgust by spending most of the decade in Europe. Societal tensions manifested in all art mediums. Artists realized America’s veneration of the new philosophy of science, industry, and capitalism. Stella’s “Bridge” (Doc B) encapsulates the triumph of modernism over traditionalism with glowing cities and cathedrals of city light. New technology also stressed the tension between old and new America. The automobile’s proliferation allowed many Americans to escape the “new problems” of the cities. At the same time, cars allowed unsupervised dating and tested the old morals and standards. Automobiles also facilitated the bootlegging industry. The 18th Amendment was a triumph of “old” America against the problems of “new” America. New immigrants could hopefully be civilized without their “rum” and soon after be cured of their “romanism” as well. The temperance experiment failed largely due to “new” automobiles and the automobile/temperance conflict is a clear demonstration of manifested tensions between modern and traditional America. Other new technologies such as the radio and telephone also created tension in America. Mass communication carried ideas, morals, and conflict to isolated parts of the nation. Part of the Scopes Monkey trial’s allure was its national radio broadcast of Darrow and Bryan’s arguments. New ideas like evolution were carried on the airwaves. Film and radio stars like Clara Bow and Rudolf Valentino became national celebrities for their charisma and appeal. These stars represented a new cult. People began to ignore the church and praise materialism and financial success. Americans’ tastes fixed upon what “the large national advertisers” told people about “individuality.” ( Doc A) In certain cases scientific progress seemed to represent American traditionalism. Charles Lindbergh’s achievements hailed as comparison to that of Jesus “nineteen hundred years ago.” (Doc F). Capitalist and entrepreneur Henry Ford saw himself as a defender of traditional America. Ford supported prohibition and vehemently opposed unions at Ford Motor Company. To Ford, unions and alcohol obviously represented the problems of the “new America.” Henry Ford and the Model T served as duplicitous symbols of old and new conflicts. Even Sunday school teachers represented the aforementioned commingling of traditionalism and modernism when called to educate the youth about the “well proven facts of science” (Doc G) in regard to smoking. It is doubtful that William Jennings Bryan would call for Sunday schools to push new scientific ideas upon the nation’s children. Throughout the post World War I era Americans were divided over the nation’s path. For modernists, the country was stuck in a quagmire of dogma and intolerance. Traditionalists believed the country was rapidly abandoning its founding racial, political, and religious doctrines. Americans could not ignore that the country was changing. Divorce rates rose, marriage rates declined (Doc H), African Americans lived in the north and south, and the white, Anglo Saxon control over the country seemed threatened. Immigration, progressivism, and the Great War introduced new values and challenged the old, leaving the country in a political and cultural struggle over its identity.