7.13 Comparative Statics in the Combined Money

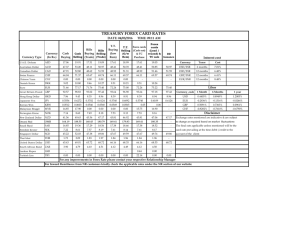

advertisement