Summary For many years students of Haitian society have

advertisement

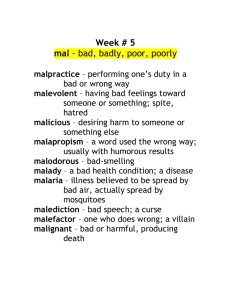

85 Journal of Ethnopharmacoiogy, 9 (1983) 85-104 Elsevier Scientific Publishers Ireland Ltd. THE ETHNOBIOLOGY OF THEl HAITIAN ZOMBI E. WADE DAVIS Botanical Museum of Harvard University, Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 (U.S.A.) (Accepted July 19,1983) Summary For many years students of Haitian society have suggested that there is an ethnopharmacological basis for the notorious zombies, the living dead of peasant folklore. The recent surfacing of three zombies, one of whom may represent the first potentially verifiable case, has focused scientific attention on the reported zombi drug. The formula of the poison was obtained at four widely separated localities in Haiti. The consistent ingredients include one or more species of puffer fish (Diodon hystrix, Diodon holacunthus or Sphoereides testudineus) which contain tetrodotoxins, potent neurotoxins fully capable of ph~~colo~c~y ~duc~g the zombi state. The ingredients, preparation and method of application are presented. The symptomology of tetrodotoxication as described in the biomedical literature is compared with the constellations of symptoms recorded from the zombies in Haiti. The cosmological rationale of zombies within the context of Voudou theology is described. Prelude laboratory tests are summarized. The anthropological and popular literature on Haiti is replete with references to zombies. According to these accounts, zombies am the living dead: innocent victims raised in a comatose trance from their graves by malevolent Voudoun priests (bokors), and forced to toil indefinitely as slaves. Although one author has attempted to prove that zombies exist (Hurston, 1981), most have rather uncritically assumed the phenomenon to be folklore (Herskovits, 1937; Leyburn, 1941; Mars, 1945; Metraux, 1959; Bourguignon, 1959; Courlander, 1960). Nevertheless, virtually all of these writers acknowledge that the majority of the Haitian population believes in the physical reality of zombies. As long ago as 1938, Zora Hurston, a student of Franz Boas at Columbia University, suggested that there could be a material basis for the zombi phenomenon. Having visited what she believed to be a zombi in a hospital near Gonaives in north central Haiti, she and the attendant physician “discussed at great length the theories of how zombies came to be. It was concluded that it is not a case of awakening the dead, but a matter of the semblance of death induced by some drug known to a few. Some secret 0378-8741/83/$06.00 o 1983 Elsevier Scientific Publishers Ireland Ltd. Published and Printed in Ireland 86 probably brought from Africa and handed down generation to generation. The men know the effect of the drug and the antidote. It is evident that it destroys part of the brain which governs speech and will-power. The victim can move and act but cannot formulate thought.” (Hurston 1981, p. 206). Although Hurston alone gave credence to this hypothesis, subsequent investigators certainly knew of the poison. Leyburn (1941) refers to “those who believe that certain bocors (sic) know how to administer a subtle poison to intended victims which will cause suspended animation and give the appearance of death” (Leybum, 1941, p. 163). According to Metraux (1959, p. 281), the hungun (Voudoun priest) know the secret of certain drugs which induce a lethargic state indistinguishable from death. Courlander (1960) adds: “the victim is not really dead but has succumbed to a virulent poison which numbs all the senses and stops bodily function but does not truly kill. Upon disintemment, the victim is-given an antidote which restores most physical processes but leaves the mind in an inert state, without will or the power to resist”. (Courlander, 1906, p. 101). Though the anthropologists remained equivocal, the Haitians themselves recognise the existence of the poison with some assurance. It was, for example, specifically mentioned in the old Code Penal, Article 249 of which reads (Leybum 1941, p. 164): “Est aussi qualifie attentat 1 la vie d’une personne, l’emploi qui sera fait contra elle de substances qui, sans dormer la mort, produisent un effet letharique phs ou moins prolong& de quelque maniere que ces substances aient administrb, quelles qu’en aient et& les suites. Si par suite de cet &at lethargique la personne a ete inhum& l’attentat sera qualifie assassinat.“’ Although it now seems remarkable that the reports of the poison were not properly investigated, there are, in fact, good historical reasons for the oversight. For one, they appeared during a period when Haitian social scientists, trained in the tradition of cultural relativism and objective analysis, were most anxious to promote the legitimacy of peasant institutions. These intellectuals in particular were repelled by the sensational writings (Seabrook, 1929; Craige, 1934) of an earlier decade which, in their minds, had both slanderously misrepresented the Haitian peasantry and rationalised the American occupation of 1915-1934 (Bastien, 1966). The subject of zombies, which had figured so prominently in the earlier writings, simply did not interest them (Faine, 1937)2. Zora Hurston bore their contempt. Louis Mars, 1Also to be considered as attempted murder, the use that may be made against any person of substances, which, without causing actual death, produce a lethargic coma more or less prolonged. If, after the administering of such substances, the person has been buried, the act shall be considered murder no matter what result follows. ‘Referring no doubt to Seabrcok (1929), Jules Faine wrote “Such legends, circumstantially garbed and presented as actual facts by certain unscrupulous authors, have served as the theme of books which have made a great commotion in foreign countries. Taking advantage of the credulity of a public avid for exotic matters, for mysteries, for the supernatural, these writers have gained, in certain circles, the greatest success of publicity.” (Faine, 1937, p. 303). 87 a leading Haitian intellectual of the period, remarked of her, “This American writer stated specifically that she came back from Haiti with no doubt in regard to popular belief in the Zombi pseudo-science. Miss Hurston herself, unfortunately, did not go beyond the mass hysteria to verify her information.” (Mars, 1945, p. 39). The case for the poison was, indeed, suspect on several grounds. Firstly, many informants insisted that the actual raising of the zombi depended solely on the magical powers of the bokor (Herskovits, 1937, p. 245; Leybum, 1941, p. 163; MCtraux, 1959, p. 282). Secondly, despite the rich body of anecdotal lore about zombies, no physician had examined a genuine case (Mars, 1945, p. 39). Thirdly, no sample of the elusive poison had been obtained for scientific analysis. Hurston (1981, p. 216) did not help her case by concluding that “the knowledge of the plants and the formulae are secret. They are usually kept in certain families, and nothing will induce the guardians of these ancient mysteries to divulge them.” Presumably, she intimated that the formula of the poison would ever remain unav~lable for scientific scrutiny. Since Hun&on, the few anthropologists to consider zombies have rejected the poison hypothesis out of hand. Bourguignon (1959, p. 40), for example, in her functional analysis of zombies as folklore, suggests that the idea of a poison allcws Haitians “to hold on to a magical belief yet give it the appearance of scientific ~pectab~ity”. Recently, however, scientific interest in the zombi poison was rekindled by the surfacing of three reputed zombies, one of whom may,be the first potentially verifiable case. The first is a woman, Natagete Joseph, aged about 60, who was reputedly killed over a land dispute in 1966. In 1979, she was recognised wandering about her home village by the police officer who 13 years before, in the absence of a doctor, had pronounced her dead. The second case was a younger woman named Francina, supposedly buried in 1976 and found in a catatonic state in 1979 by a girlfriend. In this case, a jealous husband was said to have been responsible for her demise. There were two notable features of Francina’s case; her mother recognised her by a childhood scar she bore on her temple, and later when the grave was exhumed, her coffin was found to be full of rocks (Douyon, pers. commun.). These two cases, though curious, were, in fact, no mom substantial than many others that have pe~odi~a~y surfaced in the popular press of Haiti (Mars, 1945; Hurston, 1981; Kerboul, 1973). The third case, however, was quite interesting and warranted a full investigation. In early May of 1962, Louis Ozias’ entered the Albert Schweitzer Hospital, an American directed ph~~t~opic ~sti~tion located at Deschapelle in the Artibonite Valley. Ozias had been sick with fever, body ache and general malaise for some time, but had recently begun to spit up blood. His condition deteriorated rapidly and at 02:OO h on May 3 he was pronounced dead by two attendant physicians, one of them an American. His medical dossier 3Louis Ozias, Angelina Ozias, Marie Claire Ozias are pseudonyms, as is Morbien. indicates that at the time of death, he suffered from digestive disorders, pulmonary edema, hypothermia, respiratory difficulties and hypotension (26/15). Present at his bedside was his sister, Angelina Ozias, who immediately notified the family. The elder sister, Marie Claire Ozias, saw the body and affixed her thumbprint to the official death certificate. The body was placed in a cold room for 8 h until it was taken for burial. At 1O:OO h, May 3,1962 Louis Ozias was buried in a small cemetery north of his village of Morbien, and 10 days later a heavy, concrete memorial slab was placed over the grave by his family (Douyon, 1980, pers. commun.; Angelina Ozias pers. commun. ; Louis Ozias pe,rs. commun., Pradel and Casgha, 1983). In 1981, a man walked into the Morbien market place and approached Angelina Ozias, introducing himself by a boyhood nickname of the deceased brother. It was a name that only intimate family members knew, and it had not been used since the siblings were children. The man claimed to be Ozias and said that he had beep. made a zombi by his own brother. With many other zombies, he had worked for 2 years as a slave on a northern sugar plantation, until the death of their master had freed them. For the last 18 years he claimed to have wandered the countryside, fearful of the vengeful brother. The case of Louis Ozias generated much publicity within Haiti and attracted the attention of Dr. Lamarck Douyon, the Director of the Psychiatric Institute in Port au Prince. Douyon considered various strategies to test the truth of Ozias’ claim. To exhume the grave would prove little. If the man were an imposter, he or his conspirators could well have removed the bones of Ozias. On the other hand, had Ozias actually been taken from the grave as a zombi, those responsible might have substituted another body. Instead, working directly with family members, Douyon designed a series of detailed questions concerning Ozias’ childhood - questions that even a close boyhood friend could not have answered., These were answered correctly (Douyon, pers. commun.). Over 200 residents of Morbien who had known Ozias were convinced that he had returned to the living. Fingerprint analysis by Scotland Yard conch ded that there was no reason to believe that the fingerprint on the death certificate was not that of Marie Claire Ozias (Hulse, pers. commun.). Furthermore, there was no apparent social or economic incentive to perpetrate a fraud. Douyon and others, therefore, concluded that the Ozias case represented a valid example of zombification (Douyon, pers. commun.). One of the notable features of the Ozias case was the suggestion that he had been made a zombi by a bokor who had used a poison. American and Haitian physicians close to the case recognised that the proper drug, administered in correct dosage, could lower the metabolic state of an individual to such a low point that he or she would appear dead. Fully cognizant of the profound medical potential of such a drug, they asked me in 1982 to investigate the composition of the poison in Haiti. During the course of three expeditions, the complete preparation of five poisons used to make zombies was documented at four widely separated 89 villages in HaClti.Although each geographical region has a unique poison formula, botanical and zoological determinations of the voucher specimens indicate that the principal ingredients are consistent in three of the four localities (Table 1). The plants involved include some with well known, pharmacologically active constituents and several capable of severely irritating the skin of the victim. Two species are recognised hallucinogens: Datura metel L. and Datum strumonium L., known in Haiti as concombre zombi the “zombi cucumber”. These two plants contain a number of potent alkaloids, such as scopolamine and atropine, the ingestion of which may result in amnesia among other effects. Seeds from either species of Datum may be ground into the zombi poison. A third species commonly used in the various preparations, Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC., pois a gra tter, contains psychotomimetic constituents and may have hallucinogenic activity (Schultes and Hofmann, 1980). The most consistent plant ingredient in all the various preparations of the poison is tcha-tcha (Albiezia lebbech L.), the chemistry of which is poorly known (Raffauf, pers. commun.). The irritant plants added to the preparation include species with urticating hairs (Ureru baccifera (L.) Gaud., Dalechampia scandens L.,Mucuna pruriens), anacardiaceous plants that produce severe dermatitis (Anacardium occidentale L., Comocludia giabra Spreng.), an aroid (Dieffenbachiu sequine (Jacq.) Schott.) with irritating needles of calcium oxalate in its tissues, and a number of species with spines (e.g. Zanthoxylum martinicense (Lam.) DC.). The addition of the irritants seems to be related to the way in which the poison is applied. Though topically active, any one of the variations of the poison is particularly effective if inhaled or applied to an open wound. One informant suggested pricking the victim’s skin with a thorn. Another added ground glass to the preparation. Several of the plants produce such severe irritation that the victim, in scratching himself or herself, may cause open wounds. The poison may be applied more than once to the victim, and undoubtedly these self-inflicted wounds increase susceptibility to subsequent doses. Although a number of lizards, tarantulas, non-venomous snakes and millipedes are added to the various preparations, there are five consistent animal ingredients to note: burnt and ground human remains; a small tree frog (Osteopilus dominicensis Tschudi); a polychaete worm (Hermodice carunculuta Pallas); a large New World toad (Bufo ma&us L.); and one or more species in two genera of puffer fish (Diodon hystrh L., Diodon holucanthus L. and Sphoeroides testudineus L.). In the preparation, the human remains are burnt almost to charcoal and may be considered chemically inert. The skin of the tree frog, Osteopilus dominicensis (crapaud blanc, cmpaud brun), is covered by irritating glandular secretions (Lynn, 1958), and a related species, Osteopilus septentrionalis Dumeril and Bibron has caused temporary blindness in Cuba (Williams, pers. commun.). The setae of Hermodice curunculata inflict a “paralyzing effect” (Mullin, 1923) and may be venomous (Halstead, 1978). Kennedy (1982) describes Bufo marinus as a “veritable chemical factory” 90 TABLE 1 CONSTITUENTS OF THE ZOMBI POISONS Ingredients Localitya 1 Plant Datum stramonium L., concombre zombi Mucunapruriens (L.) DC., pois a gratter Albizia lebbeck L., tcha tcha Umra baccifem (L.) Gaud., maman guepes Anacardium occidentale L., pomme acajou Comocladia glabra Spreng., bresillette Dieffenbachia sequine (Jacg.) Schott., cahnador Zanthoxylum martinicense (Lam.) DC., bois pine Dalechampia scandens L., mashasha Trichilia hirta L., consigne Tremblador, no specimen Desmembre, no specimen Amphibian Bu fo marinus L., bango Osteopilus dominicencis Tschudi, crapaud blanc Osteopilus dominicencis Tschudi, crapaud brun Fish Diodon holacanthus L., cf. bilan Diodon hystrix L., fou fou Sphoeroides testudineus L., crapaud du mer Annelids’ Hermodice Cen tiped Spirobolida, carunculata Pallas Polydesmida Arachnids Themphosidae, a Locality: tarantulas, crabe araignee 3 4 5 X X X x X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Reptile Ameiua chrysolaema Cope Leiocephalus schreibersi Gravenhorst Anolis coelestinus Cope, miti Verde Anolis cybotes Cope, zanolite Epicrates striatus (Fischer), mabouya Mammal Homo sapiens L., bones Homo sapiens L., dried flesh 2 X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X 1 is Gonaives; 2 is Saint Marc; 3 is Leogane; 4 is Gonaives; 5 is Petit Riviere. 91 Fig. 1. Dried specimen of Bufo marinus. and notes that its paratoidal glands secrete at least 26 highly active compounds. These include: (a) cardioactive steroids known commonly as bufogenins and bufotoxins; (b) phenylethylamine bases and derivatives such as dopamine, adrenaline, noradrenaline; (c) tryptamine bases and derivatives such as serotonin, cinobufagin (a powerful local anaesthetic) and bufotenin (Kennedy, 1982). As a psychoactive agent, Bufo marinus has a long history in the circumCaribbean region (Fur&, 1972, Dobkin de Rios, 1974, Kennedy, 1982). Bones of this toad were so common in middens at the site of San Lorenzo, Mexico that Michael Coe (1971) has suggested that the Olmec usedBufo marinus as a hallucinogen. At late Post Classic May sites on Cozumel, Mexico, as much as 99% of all amphibian remains have been identified as Bufo marinus (Hamblin, 1979). The possible contemporary use of the toad Fig. 2. Houngan with dried specimen. 92 as a hallucinogen in southern Vera Cruz, Mexico has been reported (Knab, unpublished). Hallucinogen or not, there is little question that, whether ingested or applied topically, the chemical constituents of Bufo marinus are potent poisons. Recent analysis of the toad’s skin has yielded substances resembling those found in African arrow poisons, such as Strophanthus gratus and S. hornbe (Flier et al., 1980 in Kennedy, 1982); in South America, the Bufo skin has been used in arrow poison preparations (Abel and Macht, 1911 in Kennedy 1982). As an arrow poison, it acts as a muscle relaxant and affects the respiratory center, and in hrge doses, it can cause death. Though native to the Americans, the toad was commonly used as a medicine/poison in Europe as early as the 16th century. In Italy, toads were placed in boiling olive oil and the poison was skimmed off the surface (Raffauf, per-s.commun.) Turning to the possible role of Bufo ma&us in the creation of zombies, it is worth considering the work of Howard Fabing, the first to experiment with bufo~nine in the 1950’s. Fabing (1956) found that injections of bufotenine into human subjects induced a state that coincided well with literary descriptions of the “Berserkers” of Norse legends. He characterised that state as one of frenzied rage, reckless courage and enhanced physical strength, and concluded that the unidentified substance ingested by the Berserkers before their raids was a bufotenine-containing creature (Kennedy 1982). What is pertinent to our present study is that the description of his experimental subject closely matches ch~act~~ations of zombies when they first come out of the grave. Informants report that the zombi must be immediately beaten and bound with rope and that as many as three men may be required to control him or her. The most interesting and potent ingredients in the poisons are the puffer fish. The Haitians recognise three varieties: the fou-fou (Diodon hystrix); the b&m (cf. Diodon holacanthus); and the crapaud du mer or seatoad (Sp~oe~~des testudineus). These three species belong to a large pantropical order of fish (Tetraodo~tiformes), many of which have a deadly nerve toxin known as tetrodotoxin in their skin, liver, ovaries and intestines. Toxin levels within the species of Diodon vary, leading some investigators to believe that the fish serve as transvectors of tetrodotoxin (Halstead, 1978). On the other hand, members of the genus Sphoeroides axe particularly virulent (Fukada, 1937; Fukada and Tani, 1937a,b, 1941; Tahara, 1896). The biogenesis of the tetrodotoxins within these fish is not yet understood, but it is of some significance to the zombi phenomenon. Of considerable interest is the reported variability of the toxin levels in natural popufations of puffer fish. Toxin levels differ not only according to sex, seasonahty and geograph.ical locality, but from individual to individual within a single population. A puffer fish from Brazil, Tetrodon psittacus is reported to be poisonous only in June and July (Gonsalves, 1907). Among Japanese species toxicity begins to increase in December, and reaches a peak in May or June (Tani, 1940). Toxicity is correlated with the reproductive cycle and is higher 93 in females, but the remarkable variability in toxin levels amongst separate populations of the same species has prompted suggestions that concentration or presence of the toxins may be correlated with food habits (Halstead, 1978). Homstedt (pers. commun.) notes that puffer fish grown in culture do not develop tetrodotoxins. It is possible that the puffer fish, in addition to synthesizing tetrodotoxins endogenously, may serve as transvectors of either tetrodotoxin or ciguatoxin, a poison of uncertain origins that contaminates many marine fish (Halstead, 1978). The symptoms of ciguatera poisoning are similar to those of tetrodotoxication and include “paresthesia with prickling about the lips, tongue and nose together with a tingling sensation in the extremities. . . a state of malaise. . . nausea, digestive distress. . . gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and nervous pain. . . death results from respiratory paralysis” (Dufra et al., 1976, p. 61). In New Caledonia, Duboisia myoporoides RBr. is used as an effective antidote in ciguatera poisoning. This plant contains nicotine, nornicotine, apoatropine, atropine and scopolamine (Dufra et al., 1976). In Haiti, although each zombi poison has a recognised antidote, the ingredients and preparations of these antidotes are completely inconsistent from one locality to another (Davis, 1983). Moreover, the antidotes are not used to resurrect the zombi from the grave, but rather as treatments to prevent the victim from dying from the poison in the first place. Virtually all of the ingredients in the recognised antidotes are either considered chemically inert, or are used in insignificant quantities. However, when the zombies are taken from the grave they are force fed a paste made from sweet potato (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Poir.), cane syrup (Saccharum officinarum L.) and concombe zombi (Datum strumonium or Datum metel). As in the case of the related solanaceous species Duboisiu myoporoides of New Caledonia, these daturas contain atropine and scopolamine and hence may be serving as an effective but unrecognised antidote to the zombi poison. It is significant to note that this possible antidote is one of the most potent hallucinogenic plants known. Duturu intoxication may be characterised as an induced state of psychotic delirium (Weil, pers. commun.). It is in the midst of this intoxication that the zombies are lead away to their workplace. The effects of tetrodotoxin poisoning have been well documented. The most famous cause of puffer poisoning is the well known culinary delicacy, the Japanese fugu fish (Fugu purdulis Temminck and Schlegel, Fugu rubripes rubripes Temminck and Schlegel, Fugu vermiculuris porphyreus Temminck and Schlegel, Fugu vermiculuris vermiculuris Temminck and Schlegel) (Hashimoto, 1979). In eating these fish the Japanese accept the obvious risks because they enjoy the exhilarating physiological after effects, which include sensations of warmth, flushing of the skin, mild paresthesias of the tongue and lips, and euphoria (Halstead, 1978). Because of its popularity as a food, and the relatively high incidence of accidental poisonings, the fugu fish has generated an enormous medical and biomedical literature. Turning to that literature for clinical descriptions and case histories, one is immediately struck by the parallels to the zombi phenomenon. 94 In describing his experience to me, Louis Ozias recalled remaining conscious at all times, and although completely immobilised, could hear his sister’s weeping as he was pronounced dead. Both at and after his burial his overall sensation was that of floating above the grave. He remembered as well that his earliest sign of discomfort before entering the hospital was difficulty in breathing. His sister recalled that his lips had turned blue. Although he did not know how long he had remained in the grave before the zombi makers came to release him, other informants insist that the zombi may be raised up to 72 h after the burial. The onset of the poison itself was described by several houngan as the feeling in victims “of insects crawling beneath your skin”. Another houngan offered a poison that would cause the skin to peel off the victim. Popular accounts of zombies claim that even the female zombies speak with deep husky voices, and that all zombies are glassy-eyed (Kerboul, 1973; Hurston, 1981). Several houngan suggested that the belly of the victim swells up after he or she has been poisoned. Recall finally that Louis Ozias’ medical symptoms at the time of his “death” included digestive troubles with vomiting, pronounced respiratory difficulties, pulmonary edema, uremia, hypothermia, rapid loss of weight and hypotension (Douyon, per-s. commun.; Pradel and Casgha, 1983). Note that these symptoms are quite specific and certainly peculiar. The literature on tetrodotoxication furnishes the following specific description of the effects. The onset and types of symptoms in puffer poisoning vary greatly, depending upon the person and amount of poison ingested. However; symptoms of malaise, pallor, dizziness, paresthesias of the lips and tongue and ataxi develop. The paresthesias which the victim usually describes as a tingling or prickling sensation may subsequently involve the fingers and toes, then spread to other portions of the extremities and gradually develop into severe numbness. In some cases the numbness may involve Fig. 3. Louis Ozias by his grave-site. 95 the entire body, in which instances the patients have stated that it felt as though their bodies were floating. Hypersalivation, profuse sweating, extreme weakness, headache, subnormal tempemtures, decreased blood pressure, and a rapid weak pulse usually appear early. Gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and epigastric pain are sometimes present. Apparently the pupils are constricted during the initial stage and later become dilated. As the disease progresses the eyes become fixed and the pupillary and cornea1 reflexes are lost. . . .Shortly after the development of paresthesias, respiratory distress becomes very pronounced and. . . the lips, extremities, and body become intensely cyanotic. Muscular twitching becomes progressively worse and finally terminate in extensive paralysis. The fist sreas to become paralyzed are usually the throat and larynx, resulting in aphonia, dysphagia and complete aphagia The muscles of the extremities become paralyzed and the patient is unable to move. As the end approaches the eyes of the victim become glassy. The victim may be comatose but in most cases retains consciousness, and the mental faculties remain acute until shortly before death. (Halstead, 1978 italics mine). Several authors report this peculiar state of profound paralysis during which time most other faculties remain normal (Leber, 1927; Fukada and Tani, 1937a, 1941; Akashi 1880). Others state that a degree of anaesthesia accompanies the paralysis (Kimura, 1927; Matsuo, 1934; Yano, 1937; Noniyama, 1942), while Fukada (1951) believes that anesthesia occurs only at or near fatal doses. Other pronounced symptoms of tetrodotoxin poisoning include pulmonary edema (Larsen, 1925; Dincan, 1951), and hypotension (various cf. Halstead, 1978). One patient who recovered stated that he had “felt numb from neck to toes, with the feeling of ants crawling over him and biting him” (Larsen, 1942, p. 417). Tahara (1896) noted that several victims of tetrodotoxin poisoning developed a distended abdomen. Ishihara (1918) stated that respiratory distress was the first symptom of the poisoning. Halstead (1978) reports that large skin blisters appear by the third day after exposure to the tetrodotoxins; by the ninth day the skin begins to peel off (Halstead, 1978, p. 457, Fig. 1). Cyanosis, vomiting and hypothermia have been reported by a number of authors (Richardson, 1893; Fukada and Tani, 1937a,b, 1941; Bonde, 1948). The poison acts on the central nervous tissues, according to some investigators (Iwakawa and Kimura, 1922; Kawakubo and Kikuchi, 1942) and both Kimura (1927) and Duncan (1951) note that the drug has a sedative, narcotic effect on the brain. Not only do the individual symptoms of zombification and tetrodotoxication sound remarkably similar, but entire case histories from the Japanese literature read like accounts of zombification. Halstead (1978) cites over 20 cases which warrant investigation, but two which he describes are very pertinent. Akashi (1880), for example, reports: A gambler ostensibly died by eating fugu, and the body was placed in storage for the officials to examine. About seven days later the man became conscious and finally recovered. The victim claimed to have recalled the entire incident and stated that he was afraid he would be buried alive. In the second case, the victim was considered dead and was placed on a cart and shipped to a crematorium in a nearby town. The man recovered from the cart and 96 walked away. This latter victim also claimed to have been aware of what was happening (Halstead, 1978, p. 714-715 j. Another relevant case study comes from the Mexican historian Francisco Javier Clavijero (Mosher et al., 1964). While searching for a new mission site in Baja California, four soldiers came upon a campfire where indigenous fishermen had left a roasted piece of the liver of some botete (Sphoeroides lob&us). Despite the warnings of their guides, the soldiers divided the meat. One of them ate a small piece, another chewed his portion without swallowing and the third only touched it. The first died within 30 min, the second soon after, and the third remained unconscious until the next day. This account illustrates certain significant features of puffer fish poisoning. Although tetrodotoxin is one of the most toxic non-protein substances known (Mosher et al., 1964, p. 1110) like any drug, its effects depend on dosage and the way it is administered.4 Having studied over 100 cases of tetrodotoxication, Fukada and Tani (1941) distinguished four degrees of poisoning. The first two are characterised by progressive hyaesthesia and loss of motor control. The third degree includes paralysis of the entire body, difficulty in breathing, cyanosis, hypotension, but with clear consciousness. In the final degree failure of the respiratory system leads to death. If the poisonous material is ingested, the onset of third degree symptoms is usually very rapid. Death may occur as soon as 17 min after the poisonous material is eaten (Richardson, 1893). Generally a crisis is reached after no more than 6 h. If the victim survives that period, he or she may expect a complete recovery. When applied topically, however, the tetrodotoxins, though active (Boy& 1911; Phisalix, 1922) are less virulent. The Haitian bokors recognise the potency of their prepamtions, and acknowledge, at least implicitly, the importance of proper application and correct dosage. Although they believe that the creation of a zombi is a magical act (see below), and that the poison always kills, they note that certain combinations of poisons are “too explosive” or that they “kill too completely”. Each poison must be carefully “weighed”; a notion that has both spiritual and practical connotations. One houngun said he had three zombi poisons, all of which included the seatoad (~p~oeroi~es ~es~~~i~e~s) ; one poison killed immediately, another caused the victim to waste away slowly, whereas the third caused the victim’s skin to peel away before death. Furthermore, the poison is never put into the victim’s food; rather it is applied repeatedly to the skin, open wounds or it may be blown across the victim so that he or she inhales it. In preparing the poisons every effort is made not to touch it. Face masks are worn, and an oily emulsion is applied to the exposed parts of all participants. 4 As an anaesthetic, the minimum detectably effective dose of tetrodotoxin of that of cocaine (Mosher et al., 1964, p. 1110). is l/160,000 97 That the Mexican soldiers in Clavijero’s account were poisoned by roasted meat exemplifies one final point especially relevant to the way the zombi poisons are prepared in Haiti. Frying, stewing, boiling or baking do not denature the tetrodotoxins (Savtschenko, 1882; Halstead and Bunker, 1953). In every documented preparation of the poison, the toad (Bufo matinus) and puffer fish (Diodon hystrh, Diodon hoZacanthus and/or Sphoeroides testudineus) are sun-dried and then placed on hot coals along with various fresh animals and human remains (Fig. 1). All the animals are broiled to a soft, oily consistency and then placed together with the plant ingredients in a mortar. All the components of the poison are pounded to a granular consistency and then sifted to produce the final product. The poisons which I collected during my first two expeditions to Haiti are currently being analysed at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. Initial experiments with rats and primates conducted by Dr. Leon Roisin at the New York State Psychiatric Institute have been most promising. Topical applications to the shaved belly of a monkey produced local edema, particularly where the skin had been nicked by the technicians. Injected intraperitoneally into rats in dosages of 5 mg/lOO g body wt, the poison induced a cataleptic Fig. 4. Preparing the poison - grating cemetary materials. Fig. 5. Preparing the poison - the mortar and pestle. 98 state. Pulse rate increased very rapidly and then gradually decreased, with respiration becoming shallower. A needle put into the tail of the test animal provoked no pain response. Though the EEG continued to register central nervous system activity, the rat became completely immobilised. Lower dosages of the poison caused pronounced reduction in activity and local paralysis, from which the rats recovered with no apparent signs of permanent injury. Based on dosages administered to rats, it can be suggested that the equivalent of an intraperitoneal dose of 3.5 g of crude poison might put a 73-kg human into a comatose, catalyptic state (Roisin, pers. commun.). These preliminary laboratory results, together with what we know from the field and from the biomedical literature suggest strongly that there is an ethnopharmacological basis to the zombi phenomenon. The consistent and critical ingredients in the poison are the puffer fish (Diodon hystrix; Diodon holacanthus and Sphoeroides testudineus), which contain known toxins capable of pharmacologically inducing physical states similar to those characterised in Haiti as zombification. That the peculiar symptoms described by Louis Ozias match so closely the quite particular symptoms of tetrodotoxin poisoning documented in the Japanese literature suggests that he was exposed to the poison. If this does not prove that he was a zombi, it does, at least, substantiate his story. In and of itself, the formula of the zombi poison explains very little about the process of zombification in the Haitian peasant society. Although the sociology of zombification will be discussed elsewhere, the full significance of the ethnopharmacological discovery will become apparent when zombies are considered within the context of Voudou theology. According to Voudou belief, man is a composite of five aspects: the z’etoile, the gros bon ange, the ti bon ange, the n ‘ame, and the corps cadawe. 5 The latter is the ‘These findings on the nature of the Voudou soul are at odds in certain ways with those of Metraux (1946) and Deren (1953). They are based, however, on extensive and separate discussions with three prominent houngan, one of whom was personally familiar with the conclusions of the earlier investigatorKMetraux himself suggested that research into the nature of the Voudou soul is made “difficult by the wide range of beliefs and theories found among Haitian Vodu (sic) worshippers according to their intellectual sophistication, their religious background and contacts with the modern world” (Metraux, 1946, p. 84). Metraux based his interpretation largely on interviews of a single female informant at the Bureau of Ethnology in Port-au-Prince. He notes that many of her statements were contradicted outright by the one houngan he also interviewed, Metraux based his conclusions on his ‘Timpression that Marie Noel’s (his informant) candid statements reflected more closely the general beliefs of the Haitian peasantry” (Metraux, 1946, p. 85). When I commented on the range of professional interpretations by anthropologists to one of my informants, I was impressed by his sophisticated response. He suggested that the diverse opinions reflected the anthropologists’ implicit assumption that every Voudou initiate or even every Voudou priest necessarily had the answers to all complex theological questions. Would one expect, he concluded, that every French peasant or even every parish priest would be able to or even interested in addressing theological issues normally considered by the Vatican alone. 99 body itself, the flesh and the blood. The n’ume is the spirit of the flesh that allows each cell of the body to function. Gros bon ange is the life force that all sentient beings share; an individual’s gros bon ange is his or her particle of that vast pool of vital cosmic energy. The ti bon ange is the aura of the individual, that spirit that creates his or her personality, character and will power. As the gros bon ange provides each person with the power to act, it is the ti bon ange that molds the individual sentiments and will to act. The z’etoile is the one spiritual component that resides not in the body, but in the sky. It is the individual’s star of destiny, and is viewed as a calabash that carries one’s hope and all the many ordered events that shall occur over the course of a single lifetime. For the voudouist, life and death stretch far beyond the temporal limits of the corps cadaure, the mere material expression of the individual. Life begins not at the physical conception of the body but at an earlier moment, when God first decides that the person should exist. Complete death is defined not as the clinical demise of the body, but as the time when each of the five aspects of man finds its ultimate goal. The n’ume6, or the spirit of the flesh is a gift from God which upon the death of the corps cadaure passes slowly into the organisms of the soil. The gradual decomposition of the corpse is a result of this slow transferal of energy, a process said to take 18 months to complete. The gros bon ange enters the individual at conception and functions only to keep the body alive. At clinical death, it returns immediately to God and once again becomes part of the great resevoir of energy that supports all life. If the gros bon ange is undifferentiated energy, the ti bon ange is the spirit directly associated with the individual. At death the ti bon ange hovers about the body for 7 days, before descending to the world of Les Invisibles beneath the dark waters. One day and one year after the death of the individual, however, in one of the most important of Voudou rites, the ti bon ange is ritualistically reclaimed and placed in a jar, the cunari. The Cunari Les Morts are fed and clothed and then during the Ibo ceremony are sent to the forest to dwell in trees or grottos where they wait. to be reborn. Over the course of 16 rebirths the same ti bon ange gradually becomes a rich repository of wisdom and knowledge. After the last incarnation, the ti bon ange goes to Dam ballah Wedo, the serpent of the sky, a god of great benevolence and trust and the resevoir of all spiritual wisdom. There the ti bon ange finally becomes undifferentiated as a part of the, Djo, the cosmic breath that envelopes the universe. This lengthy passage of the ti bon ange correspomds to the metamorphosis of the individual into pure spiritual energy. Hence with the successive passing of generations, the individual, identified with the ti bon ange, is transformed from the ancestor of a particular lineage, to the generalized ancestor of all mankind.7 The ‘The n’ame in this sense is different from the nam, a term commonly used in reference to the complete Voudou soul including the gros bon ange, ti bon ange’and the other spiritual constituents. 100 devout voudouist, thus believing in the immortality of the ti bon ange and the gros bon ange, fears death not for its finality but because it is a critical and dangerous passage during which time the five vital aspects of man dissociate themselves. Deaths.may be natural or unnatural. Natural deaths, which are considered rare, are a call from God (mort bon dieu) and examples might include a child dying from a common childhood illness or an old man passing away in his sleep. Unnatural deaths include all accidents and inevitably involve the intervention of malevolent forces. Anyone who dies an unnatural death may be made into a zombi. To create a zombi, the bokor, the malevolent Voudou priest, or the executioner must capture the ti bon ange of the victim. This is a magical act that can be accomplished in a variety of ways. A particularly powerful bokor, for example, may through his magic gain control of the ti bon ange of a sailor who dies at sea or of a Haitian who is killed in a foreign land. Alternatively, the bokor may capture the ti bon ange of the living and hence indirectly cause the unnatural death: the individual left without intelligence or will slowly perishes. One way of thus capturing the ti bon ange is to spread poisons in the form of a cross on the threshold of the victim’s doorway. The magical skill of the bokor guarantees that only the victim will suffer. Yet a third means of gaining control of the ti bon ange is to capture it immediately following the death of the corps cadaure, during the 7 days that it hovers around the corpse. Hence the bokor may or may not be responsible for the unnatural death of the victim, and the ti bon ange may be captured by magic before or after the death of the corps cadaure. Whatever the circumstances, the capture of the ti bon ange effects a split in the spiritual components of the individual and creates not one but two complementary kinds of zombies. The spirit zombi, or the zombi of the ti bon ange alone, is carefully stored in a jar and may be later magically transmuted into insects, animals or humans in order to accomplish the particular work of the bokor. The remaining spiritual components of man, the n ‘ame, the gros bon ange and the z ‘etoiZe together form the zombi cadaure, the zombi of the flesh. Of critical interest to this ethnopharmacological investigation is the fact that the bokor, in creating the zombi cadaure, may cause the prerequisite unnatural death not by capturing the ti bon ange of the living but by means of a poison which must be applied directly to the victim. Rubbed into a ‘The fate of the individual as held by the z’etoile reflects the progress of the ti bon ange. When the corps cadavre dies, the z’etoile shifts positions in the sky, a shooting star, and is refilled by a new sequence of events for the next life of the ti bon ange, a blueprint fhat will be a function of the course of the previous lifetime. If the shooting star is bright, so shall be the future of the individual. The houngan may contact the z’etoile and change the order of the impending events. 101 wound, or inhaled the poison kills the corps cadaure slowly, discreetly and efficiently. The subsequent resurrection of the zombi cadaure in the graveyard requires a particularly sophisticated knowledge of magic. Above all the bokor must prevent the transformations of the various spiritual components that would normally occur at the death of the body. First, the ti bon ange, which may float above the body like a “phosphorescent shadow” must be captured and prevented from re-entering the victim. One way to assure this is to beat the victim violently. Secondly, the gros bon ange must be prevented from returning to its source. Thirdly, the n’ame must be retained to keep the flesh from decaying. The zombi cadaure, with itsgros bon ange and n ‘ame, can function; however, separated from the ti bon ange, the body is but an empty vessel, subject to the direction of the bokor or of whoever maintains control of the zombi ti bon ange. It is the notion of alien, malevolent forces thus taking control of the individual that is so terrifying to the voudouist. In Haiti, the fear is not of zombies, but rather of becoming one. The zombi cadaure, then, is a body without a complete soul, matter without mind or mortality. For the voudouist, the creation of either type of zombi is essentially a magical process. However, in the case of the zombi cadaure, a slow acting poison may be used to induce discreetly the prerequisite unnatural death. From ethnopharmacological investigations, we know that the poison acts to lower dramatically the metabolic rate of the victim almost to the point of death. Pronounced dead by attending physicians who check for only superficial vital signs of heart beat and respiration, and therefore considered physically dead by family members and critically by the zombi maker himself, th_evictim is, in fact, buried alive. Undoubtedly, in many cases the victim does die, either from the poison itself, or by suffocation in the coffin. The widespread belief in the veracity of physical zombies in Haiti, however, is based on those instances where the victim receives the correct dosage of the poison, wakes up in the coffin and is dragged out of the grave by the zombi maker. The victim, affected by the drug, traumatised by the set and setting of the graveyard and immediately beaten by the zombi maker’s assistants, is bound and led before a cross to be baptised with a new zombi name. After the baptism, he or she is made to eat a paste containing a strong dose of a potent psychoactive drug (Datum stramonium) which brings on an induced state of psychosis. During the course of that intoxication, the zombi is carried off to be sold as a slave labourer, often on the sugar plantations. Acknowledgements This research was undertaken while I was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Doctoral Fellowship). Direct financial support for all phases of the project was generously provided by the International Psychiatric Research Foundation. My botanical determinations were verified by Prof. R.A. Howard of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard 102 University and an expert on the flcra of the Caribbean. Zoological determinations were furnished by the staff of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. In particular I would like to thank Prof. Ernest Williams and Messers Greg Mayer, Jose Rosado, Jim Knight, Franklin Ross, Karsten Hartel and John Hunter. Complete sets of voucher specimens have been deposited at the M.C.Z. (animals) and at the Economic Herbarium of Oakes Ames at the Botanical Museum of Harvard University (plants). Invaluable biblicgraphical materials were provided by Dr. Allison Kennedy (University of California, Berkeley), Prof. Bo. Holmstedt (Karolinska Institute), Dr. Bruce Halstead (World Life Research Institute),‘Prof. M.G. Smith (Yale University). The manuscript was reviewed by Prof. Smith, Dr. Timothy Plowman (Field Museum of Natural History), Dr. Andrew Weil and Prof. Richard Evans Schultes (Harvard University). I would especially like to thank Profs. Smith and Schultes for their intellectual contributions and encouragement. The preliminary foxicological laboratory work was done by Prof. Leon Roizin of Columbia University at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The zombi project was born of the vision of three men: Mr. David Merrick, Prof. Heinz Lehman and the late Dr. Nathan S. Kline. In Haiti, I received essential logistical and intellectual assistance from a number of individuals. Dr. Lamarck Douyon shared his insights concerning medical aspects of zombification and introduced me to Louis Ozias. In the Haitian countryside I worked directly with several houngan who openly shared their remarkable spiritual knowledge. In particular I would like to thank Marcel Pierre, Levoynt, Jacques Belfort and Madame Jacque, Michel Bonnet, La Bonte. To them, and to all the people of Haiti who received me so kindly I remain eternally grateful. Finally I would like to acknowledge my two colleagues Mr. Herard Simon and Mr. Max Beauvoir. Herard Simon and his wife Helen are serviteurs of the most profound awareness. One of the truly great traditional houngan of all of Haiti, Herard offered his spiritual and physical protection without which this project would never have been completed. Max Beauvoir, a man of grace and profound knowledge, was also directly responsible for the success of the project. He and his wife Elizabeth offered me their home, and provided emotional, intellectual and physical support at the most critical moments. His daughter Rachel worked with me on every phase of the fieldwork. She showed herself to be a courageous fieldworker, an insightful anthropologist and a wonderful companion. References Abel, J.J. and Macht, D.I. (1911) The poisons of the tropical toad, Bufo aqua. Journal of the American Medical Association, 56,1531-X36. Akashi, T. (1880) Experiences with fugu poisoning. Zji Shimbum, 27, 19-23. Bastien, R. (1966) Vodoun and politics in Haiti. In: Religion and Politics in Haiti, Institute for Cross-Cultural Research, Washington, DC. Bourguignon, E. (1959) The persistence of folk belief: some notes on cannibalism and zombis in Haiti Journal ofAmerican Folklore, 72 (283), 36-47. 103 Bonde, C. von (1948) Mussel and fish poisoning. 2. Fish poisoning (Ichthyotoxism). South African Medical Journal, 22, 761-762. Boy& L. (1911) Intoxications et empoisonnements. In: C. Grall and A. Clarac (Eds.), Traite’de Pathologique, Exotique, Clinique, et Therapeutique, Paris, p. 387. Coe, M.D. (1971) The shadow of the Oimecs. Horizon, Autumn, pp. 66-74. Courlander, H. (1960) The Drum and the Hoe: Life and Lore of the Haitian People, University of California Press, Berkeley. Craige, J.H. (1934) Cannibal Cousins, Minton Balch & Co. New York. Davis, E.W. (1983) Preparation of the Haitian Zombi Poison. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, in press. Deren, M. (1953) Divine Horsemen - The Living Gods of Haiti, Thames and Hudson, London. Dobkin de Rios, M. (1974) The influence of psychotropic flora and fauna on Maya religion. Current Anthropology, 15, 147-152. Dufra, E., Loison, G. and Holmstedt, B. (1976) Duboisia myoporoides: native antidote against ciguatera poisoning. Toxicon, 14, 55-64. Douyon, L. (1980) Les zombis dans le contexte vodou et Haitien. Haiti Sante, 1, 19-23. Duncan, C. (1951) A case of toadfish poisoning. Medical Journal of Austmlia, 2, 160167. Fabing, H.S. (1956) Intravenous bufotenine injection in the human being. Science, 123, 886-887. Faine, J. (1937) Philologie Creole, Port au Prince. Flier, J., Edwards, M., Daly, J.W. and Myers, C. (1980) Widespread occurrence in frogs and toads of skin compounds interacting with the ouabain site of Na+, K’, ATPase. Science, 208, 503-505. Fukada, T. (1937) Puffer poison and the method of prevention. Nippon.Zji Shimpo, 762, 1417-1421. Fukada, T. (1951) Violent increase of cases of puffer poisoning. Clinics and Studies, 29. Fukada, T. and Tani, I. (1937a) Records of puffer poisonings. Report 1. Kyusha University Medical News, 11, 7-13. Fukada, T. and Tani, I. (1937b) Records of puffer poisonings. Report 2. Zji Eisei 7, 905-907. Fukada, T. and Tani, I. (1941) Records of puffer poisonings. Report 3. Nippon Zgaku oyobi Kenko Hoken, 3258, 7-13. Furst, P. (1972) Symbolism and psychopharmacology: the toad as earthmother in Indian American XIZ Mesa Redonda - Religion en Mesoamerica, Sociedad Mexicana de. Antropologia, Mexico. Gonsaives, A.D. (1907) Peixes veneosos da Bahia. Gazette Medical de Bahia, 38, 441452. Hambiin, N. (1979) The magic toads of Cozumel. Paper presented at the 44th annual meeting of the Society for American Archeology, Vancouver, BC. Halstead, B.W. (1978) Poisonous and Venomous Marine Animals of the World, Darwin Press, Princeton, New Jersey. Haistead, B.W. and Bunker, N.C. (1953) The effect of the commercial canning process upon puffer poisoning. California Fish and Game, 39, 219-228. Hashimoto, Y. (1979) Marine Toxins and Other Bioactive Marine Metabolites, Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo. Herskovits, M.J. (1937) Life in a Haitian Valley, Alfred A. Knopf, New York. Hurston, Z.N. (1981) Tell My Horse, Turtle Island, Berkeley. Ishihara, F. (1918) Uber die physiologischen wirkungen des fugutoxins. Mitt. Med. Fak. Univ. Tokyo, 20, 375-426. Iwakawa, K. and Kimura, S. (1922) Experimentelle untersuchungen uber die wirkung des tetrodontoxins. Mitt. Med. Fak. Kaiserl. Univ. Tokyo, 17, 455-538. Kawakubo, Y. and Kikuchi, K. (1942) Testing fiih poisons on animals and report of a human case of fish poisoning in the South Seas. Kaigun Zgakukai Zasshi, 31, 30-34. 104 Kennedy, A.B. (1982) Ecce Bufo: The toad in nature and Ohnec iconography. Current Anthropology, 2 3, 27 3-290. Kerboul, J. (1973) Le Vaudou-Magie ou Religion, Editions Robert Laffont, Paris. Kimura, S. (1927) Zur kenntnis der wirkung des tetrodongiftes. Tohoku Journal Experimental Medicine, 9,41-65. Larsen, N.P. (1925) Fish poisoning. Queen’s Hospital Bulletin, 2, l-3. Larsen, N.P. (1942) Tetrodon poisoning in Hawaii. Proceedings of the 6th Pacific Science Congress, 5, 417-421, Leber, A. (1927) Uber tetrodonvergiftung. Arb. Trap. Grenzgebiete, 26, 641-643. Leyburn, J.G. (1941) The Haitian People, Yale University Press, New Haven. Lynn, W.G. (1958) Some amphibians from Haiti and a new subspecies of Eleutherodactylus schmidti. Herpetologica, 14, 153-157. Mars, L.P. (1945) The story of Zombi in Haiti. Man, 46, 38-40. Matsuo, R. (1934) Study of the poisonous fishes at JaIuit Island. Nanyo Gunto Chihobyo Chosa Ronbunshu, 2, 309-326. Metraux, A. (1946) The concept of soul in Haitian Vodu. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 2, 84-92. Metraux, A. (1959) Voodoo in Haiti, Oxford University Press, New York. Mosher, H.S., Fuhrman, F.A., Buchwald, H.D. and Fischer, H.G. (1964) Tarichatoxin tetrodotoxin: A potent neurotoxin. Science, 144, 1100-1110. Mullin, C.A. (1923) Report on some polychaetous annelids; collected by the BarbadosAntigua expedition from the University of Iowa in 1918. Univ. Iowa Studies Nat. His, 10, 39-45. Noniyama, S. (1942) The pharmacological study of puffer poison. Nippon Yakubutsugaku Zasshi, 35, 458-496. Phi&ix, M. (1922) Animaux uenimeux et uenins. 2 vols., Masson et Cie., Paris. Pradel, J. and Casgha, J. (1983) Haiti: la republique des morts vivants, Editions du Rocher, Paris. Richardson, B.W. (1893) Fish-poisoning and the disease “siguatera.” Asclepiad, London, 10,38-42. Savtschenko, P.N. (1882) A case of poisoning by fish. Medits. Pribav. Morsk. Sborniku, St. Petersburg, 9, 55-61. Seabrook, W.B. (1929) The Magic Island, George G. Harrap & Co., London. Schultes, R.E. and Hofmann, A. (1980) The Botany and Chemistry ofHallucinogens, 2nd edn., Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL. Tahara, Y. (1896) Ueber die giftigen bestandtheile des tetrodon. Congr. Znternat. Hyg. Demog., C.R. 1894 (Budapest), 8, 198-207. Tani, I. (1940) Seasonal changes and individual differences of puffer poison. Nippon Yaku bu tsugaku Zasshi, 29, l-3. Yano, I. (1937) The pharmacological study of tetrodotoxin. Pukuoka Med. Coil., 30, 1669-1704.