Critical Approaches to Literature - Prof. Mitch's English Comp Courses

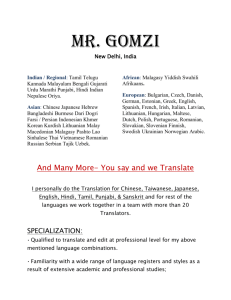

advertisement