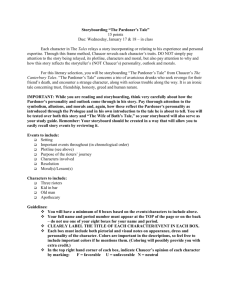

The Pardoner's Tale

advertisement

Structure, Form and Theme in “The Pardoner’s Tale” Schools Programme 2013 Dr Stephen Kelly s.p.kelly@qub.ac.uk Reading Chaucer at A-level •analyse the poet’s use of such poetic methods as form, structure, language and tone; and •show knowledge of the context of the poems by drawing on appropriate information from outside the poetry text Show knowledge of the context The Genre of the “Pardoner’s Tale” • A parodic sermon... • Sermons more popular than novels among readers until the end of the 18th century... • The sermon as an art-form • Readerly pleasure in appreciating the intertextuality of a sermon: its allusions, references, and echoes... Show knowledge of the context • Chaucer and medieval “anti-clericalism” • Anti-clericalism and the demand for reform • Wycliffism and Lollardy • The Lollard critique of sacramental theology • On the powers and authority of priests Show knowledge of the context Chaucer and medieval “anti-clericalism” • Anti-clericalism in context - an attitude, genre of complaint or satire which emerges in response to the poor education of the clergy • Anti-clerical texts were just as often written by members of the Church • These texts increasingly attacked the materialism of the Church, as well as affective devotional practices • E.g., pilgrimages, religious processions and plays, which encouraged the devout to identify emphatically with Christ, the Virgin Mary or saints... Show knowledge of the context Anti-clericalism and the demand for reform • Anti-clericalism a by-product of the Church’s own reformist efforts which began in the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 • A meeting organised by Pope Innocent III of hundreds of bishops and priests with the aim of reforming Church doctrine • From the thirteenth century onward there is an effort on the part of the Church to educate the laity in the basics of the faith, using the vernacular, art and drama Show knowledge of the context Anti-clericalism and the demand for reform • Pastoral writing and catechesis - based on the catechism: the articles of the faith • New holy orders: “mendicants” (friars such as the Franciscans and Dominicans) and new devotional practices, such as pilgrimage... • The formalisation of the seven sacraments of the Church is a result of this reform • Eucharist - doctrine of transubstantiation: the accidents of bread; the substance of Christ’s body Rogier Van Der Weyden, The Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, c. 1436 Show knowledge of the context Wycliffism and Lollardy • A more radical demand for reform emerges in England in Chaucer’s lifetime • John Wyclif, an Oxford theologian, begins to criticise the central doctrines of the Church • In 1382, London was scandalised by the efforts of its Archbishop, Courtenay, to condemn Wyclif’s teaching as heresy, at a meeting called the Blackfriars’ Council. • Chaucer was aware of Wycliffite theology and had friends who were later identified as, or declared themselves to be, followers of the controversial theologian. • The authorities labelled Wycliffites “Lollards” Show knowledge of the context Wycliffism and Lollardy • Wyclif demanded reform of the ecclesiastical structures of the Church • He demanded a Bible in English, rather than Latin, so that lay people could read Scripture for themselves • He rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation • He opposed most of the sacraments, particularly confession... Show knowledge of the context The Lollard critique of sacramental theology • “Oure usuel preshod, the qwich began in Rome, feynid of a power heyere than aungelis, is nout the preshod the qwich Cryst ordeynede to his apostlis. This conclusion is prouid for the presthod of Rome is mad of signis, rytis and bisschopis blissingis, and that is of litel uertu, nowhere ensampled in holi scripture” - The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards • Can a corrupt priest administer the sacraments without poisoning them? Show knowledge of the context On the powers and authority of priests • Is the Eucharist transformed by the priest or is the priest merely a conduit? • Act or actor? • Hoc est corpus meum • “This is my body” • Hocus pocus? Of the sacrament of the altere In sygt and in felyng, thou semest bred, In byleue, flesch, blod, and bon; In sygt and felyng thou semest ded, In byleue, lyfto speke and gon. In sygt and felyng nother hond ne hed, In byleve both God and man - early fifteenth century Rogier Van Der Weyden, The Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, c. 1436 Show knowledge of the context Questions for the Pardoner’s sermon... • Is the morality of the tale intact because of its inherent virtue - OR • Is the morality of the tale compromised because of the Pardoner’s confession of his corruption - by actor’s lack of virtue? “If our preaching is in vain, your faith is also vain (1 Corinthians 15:14)... Whoever utters a falsehood in preaching, so far as he is concerned, makes faith void” - St Thomas Aquinas Form, structure, language and tone Chaucer’s knowledge of the sermon structure • Theme - Radix malorum est cupiditas • Pro-theme - Examples: Lot, Herod, John the Baptist • Distinctions - Versions of greed: eating, drinking, gambling • Amplifications - Authorities cited in support of the Pardoner’s “argument” • Exemplum: The Three Riotours • Ventriloquism or sermon with genuine moral insight? Form, structure, language and tone Deconstructing the sermon: theme • The Pardoner envisages greed in all its forms, with no sense of irony given his own confessio • “They daunce and pleyen at dees both day and nyght” (467) • “Our blissed Lordes body they totere” (474) In illustration of his homiletic expertise, the Pardoner immediately invokes Christ’s Passion and the Eucharist Jean Fouquet, Crucifixion, 15th century manuscript illumination Form, structure, language and tone Deconstructing the sermon: form vs. substance Examine the Pardoner’s use of rhetorical techniques such as “apostrophe” and “amplificatio”: • “O glotonye, ful of cursednesse O cause first of oure confusioun Original of our damnatioun” (498-500) • “O wombe, O bely, O stinkyng cod Fulfild of donge and of corrupcioun” (534-35) • Do these enhance the sermon’s morality or are they merely a performative addition to enhance the authority of the Pardoner? Form, structure, language and tone Parodying Scripture and Eucharistic doctrine • For he that eateth and drinketh unworthily, eateth and drinketh damnation to himself, not discerning the Lord’s Body (St Paul, I Corinthians 12: 29) • They daunce and pleyen at dees bothe day and night, And eten also and drinken over hir might Thurgh which they doon the devel sacrifyce Withinne the develes temple, in cursed wyse (467-70) • Thise cookes, how they stampe, and streyne and grinde, And turnen substance into accident (538-39) Form, structure, language and tone Distinctions - Versions of greed: eating, drinking, gambling • The Pardoner confuses homiletic commentary with confession of his own experience • Imagery prefigures the action of the narrative exemplum to come For dronkenesse is verray sepulture Of mannes wit and his discrecioun, In whom that drynke hath dominacioun. He kan no conseil kepe, it is no drede. Now kepe yow fro the white and fro the rede, And namely, fro the white wyn of Lepe, That is to selle in fysshstrete, or in Chepe. This wyn of Spaigne crepeth subtilly In othere wynes, growynge faste by, Of which ther ryseth swich fumositee, That whan a man hath dronken draughtes thre And weneth that he be at hoom in Chepe, He is in Spaigne, right at the toune of Lepe, Nat at the Rochele, ne at Burdeux toun; And thanne wol he seye "Sampsoun, Sampsoun!" - 558-572 Form, structure, language and tone The Exemplum • Sources and analogues in Sanskrit (Indian), Islamic, Italian, Spanish and French literature and folk culture • The Flemish setting - Flanders was the scene of enormous financial success followed by a “crash” at the end of the century • Flemish merchants were caricatured as greedy and untrustworthy • The region had, like most of Europe, been devastated by the Plague of 1349 and following Form, structure, language and tone The Exemplum • Narrative constructed almost entirely in dialogue • Allegorical: its surface action is assumed to signify something else (namely, the exemplum on the consequences of greed) • Naturalistic: the description of the tavern, the apothecary and so on • Contrasts: the fraternity of drinkers collapses into murderous competition when they discover the treasure Attitudes to death: a medieval wedding gift... a ‘love chest’... Form, structure, language and tone The Exemplum • Who is the Old Man? • The Wandering Jew? (“Hem thoughte that Jewes rente hym not ynough”) • A personification of Death? • Elde, an allegorical figure of old age? From the Hours of Anne of France, c. 1470 Form, structure, language and tone Elde, an allegorical figure of old age? This olde man gan looke in his visage, And seyde thus: "For I ne kan nat fynde A man, though that I walked into Ynde, Neither in citee nor in no village, That wolde chaunge his youthe for myn age; And therfore mooth I han myn age stille, As longe tyme as it is Goddes wille. Ne Deeth, allas, ne wol nat han my lyf. Thus walke I lyk a restelees kaityf, And on the ground, which is my moodres gate, I knokke with my staf bothe erly and late, And seye, “Leeve mooder, leet me in! Lo, how I vanysshe, flessh and blood and skyn! Allas, whan shul my bones been at reste? Mooder, with yow wolde I chaunge my cheste, That in my chambre longe tyme hath be, Ye, for an heyre-clowt to wrappe me." Form, structure, language and tone The Exemplum • Elde, an allegorical figure of old age? The thirde was a laythe lede lenyde one his syde, A beryne bownn alle in blake, with bedis in his hande; Croked and courbede, encrampeschett for elde; Alle disfygured was his face, and fadit his hewe, His berde and browes were blanchede full whitte, And the hare one his hede hewede of the same. He was ballede and blynde, and alle babir lippede, Totheles and tenefull, I tell 3owe forsothe; And euer he momelide and ment and mercy he askede, And cried kenely one Criste and his crede sayde, With sawtries full sere tymes, to sayntes in heuen; Envyous and angrye, and Elde was his name. - The Parliament of the Three Ages Heronymous Bosch, Death and the Miser, c. 1490 Form, structure, language and tone The setting of the treasure • returns us to the Pardoner’s preoccupation with the language of Christ’s passion and the Eucharist • allegorically, the tree is the site of mankind’s Fall from Paradise • and it is Golgotha, the place of skulls • Christ’s selfless death contrasted with the thieves’ betrayal of one another Show knowledge of the context The Pardoner as subversive of clerical authority • The Pardoner’s ambiguous sexuality • A subverted confession - to glorify sin rather than to repudiate sin • A perverted sermon - a moral tale told for an immoral purpose • A parodic exemplum - a warning against avarice told out of avarice • A perverted benediction - a spiritual blessing given to deceive the faithful Form, structure, language and tone • The epilogue: performance versus belief (act or actor?) • The Pardoner’s lack of self-knowledge • sexual ambiguity = moral confusion • The Pardoner seems to have forgotten his opening “confession” • Chaucer implies that the Pardoner’s speech is mere performance without substance (action without belief) Form, structure, language and tone Dilemmas of interpretation • without the prologue, would the tale be unproblematically moral? • Is Chaucer criticising the Church or is he highlighting the possibility of its institutions being exploited unscrupulously? • Can spiritual things be expressed materially? Recent critical approaches (email me for relevant references) • Re-thinking the role of Pardoners (Alistair Minnis) • ‘Queering’ the Pardoner (Monica McAlpine; Carolyn Dinshaw; Glenn Burger) • Deconstructing the self in the Pardoner’s Prologue (H. Marshall Leicester) • The Pardoner’s Prologue and Tale, economic production, ‘material culture’ (Lee Patterson; Sarah Stanbury; Caroline Walker Bynum) • Recommended: Chaucer: Contemporary Approaches, eds. Suzanna Fein and David Raybin (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011)