Joan Didion's "On Morality" Essay Excerpt Analysis

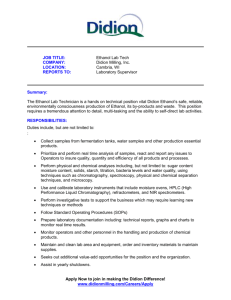

advertisement

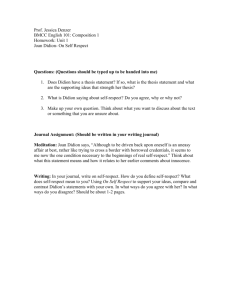

Excerpt from Joan Didion’s “On Morality” In her essay “On Morality,” published in 1965, Joan Didion argues that the only legitimate social code is “wagon train morality.” In other words, when someone is killed, we have a moral imperative to stay with the body -- not to abandon the corpse to be eaten by animals or even, in desperate circumstances, by humans. Read the passage carefully, and then answer the questions that follow. Of course you will say that I do not have the right, even if I had the power, to inflict that unreasonable conscience upon you; nor do I want you to inflict your conscience, however reasonable, however enlightened, upon me. (“We must be aware of the dangers which lie in our most generous wishes,” Lionel Trilling once wrote. “Some paradox of our nature leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the objects of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then of our wisdom, ultimately of our coercion.”) That the ethic of conscience is intrinsically insidious seems scarcely a revelatory point, but it is one raised with increasing infrequency; even those who do raise it tend to segue with troubling readiness into the quite contradictory position that the ethic of conscience is dangerous when it is “wrong,” and admirable when it is “right.” You see I want to be quite obstinate about insisting that we have no way of knowing – beyond that fundamental loyalty to the social code – what is “right” and what is “wrong,” what is “good” and what “evil.” I dwell so upon this because the most disturbing aspect of “morality” seems to me to be the frequency with which the word now appears; in the press, on television, in the most perfunctory kinds of conversation. Questions of straightforward power (or survival) politics, questions of quite indifferent public policy, questions of almost anything; they are all assigned these factitious moral burdens. There is something quite facile going on, some self-indulgence at work. Of course we would all like to “believe” in something, like to assuage our private guilts in public causes, like to lose our tiresome selves; like, perhaps, to transform the white flag of defeat at home into the brave white banner of battle away from home. And of course it is all right to do that; that is how, immemorially, things have gotten done. But I think it is all right only so long as we do not delude ourselves about what we are doing, and why. It is all right only so long as we remember that all the ad hoc committees, all the picket lines, all the brave signatures in The New York Times, all the tools of agitprop straight across the spectrum, do not confer upon anyone any ipso facto virtue. It is all right only so long as we recognize that the end may or may not be expedient, may or may not be a good idea, but in any case has nothing to with “morality.” Because when we start deceiving ourselves into thinking not that we want something or need something, not that it is a pragmatic necessity for us to have it, but that it is a moral imperative that we have it, then is when we join the fashionable madmen, and then is when the thin whine of hysteria is heard in the land, and then is when we are in bad trouble. And I suspect we are already there. 1. Which is the best meaning of “facile” (line ___) in the context of the passage? A. simple B. pleasing C. shallow D. effortless E. cheap 2. Didion shifts between “you,” “I,” and “we.” Which of the following best describes the purpose of the shifting point of view? I. Didion presupposes an opposition between the speaker (“I”) and reader (“you”). II. Didion uses the “we” to imply that all we are all susceptible to self-delusion. III. Didion uses the “we” in order to engage the reader’s sympathy. IV. By addressing the reader as both “you” and “we,” Didion emphasizes the ambivalence of the speaker’s position. A. B. C. D. E. I and II only I and III only I, II, and III III and IV only II, III, and IV 3. All of the following are true about Didion’s purpose for quoting Trilling (lines 3-7) EXCEPT a. To enhance the credibility of Didion’s overall argument. b. To provide a parenthetical counter-argument. c. To provide a more generalized context for Didion’s particular argument concerning conscience. d. To amplify the paradoxical nature of human thinking and behavior. e. To warn of a dangerous tendency people often display. 4. Which of the following verbs best expresses Didion’s overall aim in this passage? a. to extol b. to intensify c. to pacify d. to enrage e. to illuminate 5. What can the reader infer would be Didion’s opinion of one who claims to perform acts out of sheer altruism? a. Didion would refute this claim. b. Didion would propagate this claim. c. Didion would allow that such a claim is entirely dependent on the claimant’s motivations. d. Didion would concede that such a claim shows deep introspection. e. Didion would vehemently deny the claimant’s right to make such a statement. 6. What is the rhetorical effect of Didion’s use of parallelism with the list of “all the” examples in lines (23-24)? (A) The repetition emphasizes a common theme of non-intrinsic virtue among “ad hoc committees,” “picket lines” “brave signatures” and “tools of agitprop.” (B) The parallel structure works in conjunction with her repetition of “it is all right only so long as” in order to clarify her definition of morality. (C) It creates a crescendo of importance for each subsequent example. (D) It centers the reader’s attention around her central point. (E) The use of “all” serves to persuade the reader that what matters most is not so much the actual examples as their pervasiveness. 7. Which of the following is true regarding the pronoun “it” (line 8)? I. its antecedent is “the ethic of conscience” II. its antecedent is “a revelatory point” III. the speaker goes on to further clarify and criticize the use of the antecedent of “it” IV. “it” in line 10 refers to the same antecedent as the “it” in line 8 (A) I only (B) II only (C) II and III (D) I and IV (E) II, III and IV 8. Based on this passage, if Didion wanted, at age 5, to be a particular animal, which animal would she be? a. b. c. d. e. f. A lion A tiger A combination of A and B, hence an animal drawn by Napolean Dynamite. A starfish An indefinable creature whose prose is virtually inscrutable A smidgen of a small part of all the above (ish)