Policy Entrepreneurs and the Design of Public Policy: Conceptual

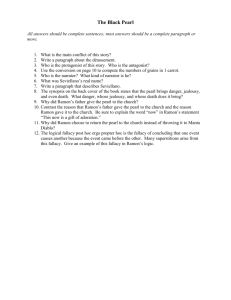

advertisement