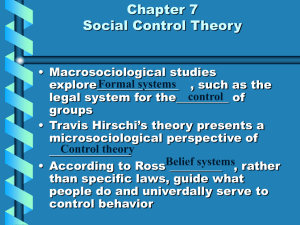

RECKLESS REEVALUATED: CONTAINMENT THEORY AND ITS

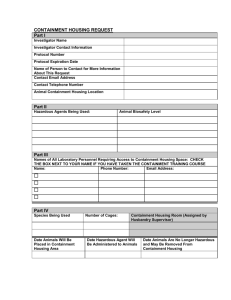

advertisement