Higgins, "Homicide Life on the Street: Realism"

advertisement

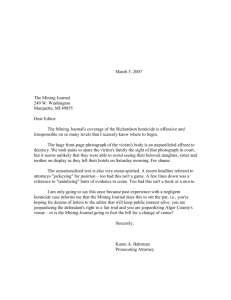

1 Homicide Realism Ba mb i L. Hagg in s Abstract: One of the most critically acclaimed but low-rated dramas in network television history, Homicide: Life on the Streets approached the cop show genre by trying to remain true to actual police work and life in Baltimore. Bambi Haggins explores this commitment to realism by investigating the narrative and stylistic techniques employed by the show to create its feeling of authenticity. Homicide: Life on the Streets (NBC, 1993–1999), one of the most compelling and innovative cop dramas ever aired on U.S. network television, occupies a significant, if often overlooked, position in the history of television drama. Homicide is the “missing link” between the quality dramas of the 1980s, such as Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981–1987), and groundbreaking cable series unencumbered by network limitations, like The Wire (HBO, 2002–2008). While Homicide continues the “quality” tradition from its NBC dramatic forbearers—the multiple storylines, overlapping dialogue, and cast of flawed protagonists in Hill Street Blues, and the cinematic visual style and the city as character in Miami Vice (NBC, 1984– 1989)—it manages to convey a sense of immediacy and intimacy that can be as disquieting as it is engaging. Based on David Simon’s nonfiction book, Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, which chronicled his year “embedded” with Baltimore’s “Murder Police,” Homicide does little to assuage the audience’s anxieties; rather, it brings a messy and unsettling slice of American urban life to network television. As a twentieth-century cop show, it offers an inspirational model for twenty-first-century television drama. We might consider Homicide’s commitment to realism in terms comparable to those of the “RealFeel” index, a meteorological measure that takes into account humidity, precipitation, elevation, and similar factors to describe what the temperature actually feels like. Thus, by examining the look, the sound, and, most significantly, the sense of Homicide, and by attending to facets of “emotional 13 14 Bamb i L. Haggin s realism” and “plausibility, typicality, and factuality” of the series, we can describe its “RealFeel” effect. Though “RealFeel” synthesizes a variety of specific qualities, this essay focuses on signifiers of realism that build upon each other, resonate for the viewer, and make the televisual world of Homicide, its people, and its stories feel real: socio-culturally charged, unpredictable narratives with crisp and edgy dialogue; a sense of verisimilitude in terms of both the historical moment and the place; a cast of complex characters in a culturally diverse milieu; and the sampling of generic conventions combining dark comedy, gritty police drama, and contemporary urban morality tale within each episode. These elements are not unique to this series—not when Homicide owes a debt to Hill Street Blues, and The Wire owes a debt to Homicide. While all three combine the highly evocative, and sometimes unsettling, visual style and the narrative complexity we have come to expect of quality television drama, each series builds upon the other, refining its sense of the real. The multiple storylines and flawed protagonists of Hill Street Blues give way to Homicide’s extended story arcs (across episodes and seasons), nuanced depictions of conflicted characters, and an incisive view of Baltimore in the 1990s. The Wire mobilizes—and expands upon—all of the aforementioned elements of “RealFeel” in its made-for-HBO drama. Both the televisual milieu of Hill Street Blues, an inner city precinct in an unnamed urban space, and the multiple factions in The Wire, including Baltimore’s police, government, unions, and schools, which are tainted to various degrees by corruption, resonate differently for audiences than the televisual milieu of Homicide. The Wire adheres closely to the multifaceted nature of the body of creator David Simon’s journalistic work (which includes the corner, the precinct, and the press room), and, thanks to freedoms offered by the premium cable HBO network presents an unfiltered vision of Baltimore. Homicide, while undoubtedly ambitious, is more modest in its aspirations. Like the book upon which it is based, the focus is narrow: one work shift in one squad in one precinct, which makes the depiction of a small slice of Charm City more plausible and, arguably, more intimate. Some might argue that the more controversial NYPD Blue (ABC, 1993–2005) covered similar narrative terrain and that its much-publicized instances of nudity and swearing pushed the boundaries of network television.1 However, by utilizing the generic conflation of procedural and melodrama, NYPD Blue offers a more palatable—if provocative—televisual meal for primetime audiences. Homicide, a series in which issues of class and race are always part of the narrative roux, is often not easily digestible—nor is it intended to be. The lives and the work of homicide detectives are not easy: they deal daily with death. By spurning, for the most part, the violence of chases and shootouts typical of conventional cop shows, these Charm City stories achieve their “RealFeel” by offering a condensation of Homicide 15 the everyday drama of being Murder Police—the cynicism, the frustration, the humor and the responsibility of “speaking for the dead. ” David Simon once said, “The greatest lie in dramatic TV is the cop who stands over a body and pulls up the sheet and mutters ‘damn’. . . [T]o a real homicide detective, it’s just a day’s work.”2 From the very beginning of the series, Homicide endeavors not to lie. The signifiers of “RealFeel” can be seen in the opening scene of the first episode where we are thrown into a case in progress. In a dark, rain-drenched alley, Lewis and Crosetti are on the verge of calling off their half-hearted search for evidence—and the first lines of the series express their frustration: Lewis: If I could just find this damn thing, I could go home. Crosetti: Life is a mystery. Just accept it. Beginning the series with a sense of frustration and disorientation captures the tone of daily life for Murder Police; neither the visual nor the narrative depiction is idealized. In physical terms, Crosetti and Lewis are clearly not the detective pinups of Miami Vice, nor do they have the unspoken closeness of the original troubled twosome of NYPD Blue. They are not the interracial partners favored by Hollywood films like Lethal Weapon (1987), in which the two who make up the odd couple come to know and care for each other. Lewis and Crosetti talk past each other, not really connecting with or acknowledging the other’s views, with the result often playing as comedy. In the opening scene of the series, the quotidian woes of partnership are uppermost. Thereafter, Lewis and Crosetti continue to grouse, as the latter spouts his profundities and the former counters by casting aspersions on his partner’s ethnic background (such as “salami-head”). The visual style matches the viewer’s sense of the narrative flow—the camera pulls in as if trying to catch up to the two detectives, following their exchanges and their movement through the alley. The audience is drawn into a scene that, despite appearing mundane, is disorienting; while it is initially unclear what exactly the two are doing, their states of mind appear crystalline. Lewis is “done” in multiple ways: done searching, done listening, and, on some level, done caring. In contrast, Crosetti is waxing philosophical about the search. As they move out of the alley and towards the light on the corner, a couple of uniformed cops and the victim, splayed on the ground with a bullet in his head, come into view. Lewis and Crosetti’s tired banter, like the scene itself, creates the sense that solving murders is just another job—without the flourish of flashy crime-scene investigation or the romance of crusading cops. Overzealousness is seen as poor form. Lewis responds to the uniforms’ attempts to engage him with thinly veiled hostility: “Ain’t no mystery, the man who shot him wanted 16 Bambi L. Haggin s him dead.” Crosetti’s observation that the victim “tried to duck” meets with no sympathy from Lewis—“A lost art: ducking”—who mistakenly assumes that the shooting is drug-related. The scene is a commonplace for this pair and for the place, inner city Baltimore in the 1990s. The visual bleakness, the dark humor, and the casual lack of empathy shown by Lewis and Crosetti, for each other and for the victim, combine as signifiers for the “RealFeel” of Homicide. The camera work in that premiere episode (“Gone for Goode,” January 21, 1993) also contributes. With Academy Award–winning filmmaker, native Baltimorean, and series executive producer Barry Levinson as director, and with documentarian Jean de Segonzac as cinematographer, Homicide’s signature visual style is established through the use of hand-held cameras. These swoop shakily in and out of the action at times, trying to capture all movement and thus constructing a frenetic scene; or at other times, they simply appear to record, without any stylistic flourish. Close-ups of the victims provide an intimate and unromantic view of the initial investigative process. Similar visual techniques capture the dance between the detectives and suspects during interrogation. Whether set in a back-alley crime scene, the drab squad room, or the claustrophobic minimalism of the “Box” (interrogation room), scenes are drained of color as if to signify the soul-sapping nature of the job. Jump cuts and play with perspective and point of view create a distinctive, raw, and artsy look for Homicide that functions in harmony with and in counterpoint to the narrative flow. The effect is part documentary, with the unflinching witnessing of Harlan County USA (1976), and part French New Wave, with the intimacy and evocative camera movement in Breathless (1960). Thus, the visual and narrative style act in concert to provide audiences with an understanding of the moment and of the place that has an aura of authenticity, and construction of character and situation feel emotionally realistic from the outset as well. Indeed, Homicide marries the incisiveness of Simon’s case studies and the collective vision of the creative team that was led by Levinson and included the award-winning television writer-producer and showrunner Tom Fontana, known for his groundbreaking television (St. Elsewhere and, later, Oz), as well as creator Paul Attanasio, who fictionalized Simon’s book for the small screen and would later adapt Donnie Brasco (1997). Since early in his career, Levinson had been sending cinematic love letters to Baltimore through his visions of Charm City in Diner (1982), Avalon (1990), and, Liberty Heights (1999). By contrast, Homicide’s vision of Baltimore is not colored by nostalgia; rather, the series, by design, depicts a city that is both a microcosm of 1990s urban America and a socio-culturally unique space. Here, it is worth emphasizing that attempting to arrive at any singular definition of the “real” necessarily poses pragmatic, theoretical, and existential Homicide 17 problems. Yet, it is possible to address the matter in another way by drawing on the work of media theorist Alice Hall, who describes a range of elements that establish how “real” a series feels to an audience: whether the events could have happened (“plausibility”); whether the characters are “identifiable” (“typicality”); and, the “gold standard” of television realism, whether the story is based on actual events (“factuality”).3 Indeed, Hall’s “continuum of realism” offers a framework that encompasses signifiers of Homicide’s “RealFeel” such as the choice to shoot on location in Baltimore, the use of the term “Murder Police” (Baltimorean lingo), and the creation of an ethnically, economically, and racially diverse televisual milieu. Moreover, the construction of Homicide’s fictional detectives was informed by the actual ones described in Simon’s book, which also adds to the series’ verisimilitude. However, the characters reflect the police force that one might expect to find in a city with a majority black population; thus, the majority white squad room from the book was diversified. Furthermore, the creative powers on Homicide did not succumb to the “majority hotness” requirement of most primetime dramas. In other words, the squad was cast to look the way that people actually do in real life, not on television. In the process of adaption of the book to the series, Lt. Gary “Dee” D’Addario became Lt. Al “Gee” Giardello, whose Sicilian lineage remained an essential part of the shift commander’s persona; while the gender of Det. Rich Garvey was changed, Det. Kay Howard retained the reputation for putting down all of her cases, like her original; the white Det. Donald Waltemeyer, who played a minor role in the book, became Det. Meldrick Lewis, whose character provided a black Baltimorean view (from the projects to Murder Police) that differed significantly from that of Gee and of the highly educated New York transplant, Det. Frank Pembleton. Homicide’s varied (and progressive) depictions of black characters in an arguably idealistically integrated workplace were groundbreaking and remain uncommon. While endeavoring to capture the socio-political and sociocultural complexity of the “Not quite North, Not quite South” urban space, the series plays with preconceived notions about urban American ills. The city of Baltimore depicted in the series still bears the scars of the 1968 riots, white flight, long-term unemployment, poverty, the scourge of crack cocaine in the 1990s, which has since waned, and the decades-long heroin epidemic, which has not. In Charm City, social problems are almost never as simple as they seem and, as seen in Homicide, the signifiers of “RealFeel,” within the continuum of realism, reveal complexity, conflict, and contradiction. The “RealFeel” of Homicide can also be understood in relation to Ien Ang’s assertion that “what is recognized as real is not knowledge of the world, but a subjective experience of the world: a ‘structure of feeling.’”4 The inherent drama of Homicide and its “RealFeel” come into focus most clearly through nuanced—and 18 Ba mb i L. Haggins seemingly incidental—exchanges: within backstories, idiosyncratic dialogue, and ticks of persona. Fleeting glimpses of detectives’ internal angels and demons inflect the narrative: there is more to the characters’ inner lives underneath the surface. Consequently, the audience’s “subjective experience of the world” of Homicide is rooted in the worldview of Murder Police, for whom exposing the darker side of human nature is commonplace and for whom every victory is tinged with loss. The characters in the series that best encapsulate the complexity, conflict, and contradiction of Homicide are Tim Bayliss and Frank Pembleton, arguably the program’s central partners, due in no small part to the stellar performances of Kyle Secor and Andre Braugher, respectively. Bayliss and Pembleton can initially be viewed as binary opposites—idealist versus pragmatist, native versus transplant, white versus black, emotional versus intellectual. In the series premiere, Bayliss first enters the squad room as a transfer to the division, his box of possessions in hand, believing he will live his dream: “Homicide—thinking cops. Not a gun,” he says as he points to his head. “This.” His idealized vision of working homicide can be contrasted with Pembleton’s monologue as he prepares to enter the Box, where he is king, with Bayliss: What you will be privileged to witness will not be an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship as silver-tongued and thieving as ever moved used cars, Florida swampland, or Bibles. But what I am selling is a long prison term, to a client who has no genuine use for the product. While the actual interrogation is quick and manipulative, it provides the first demonstration of the differences in perspective between the new partners. Pembleton refuses to let Bayliss view this case in crisp, clean absolutes as he forecasts the young white male suspect’s path through the system: his being re-cast by the defense attorney from murder suspect to an innocent seduced by an older male predator in a way that plays upon the predispositions of the jury pool and negates the voluntary nature of his actions. The case, with its cynical—and accurate—take on the course of justice, is the first of many that will make Bayliss question his beliefs in fundamental ways. In Bayliss’s first case as primary investigator, the victim, Adena Watson, is an eleven-year-old black girl with the “face of an angel.” From the moment he flashes his ID and tentatively says, “Homicide,” this case becomes his long-term obsession, extending throughout the life of the series. While trying to speak for Adena, Bayliss finds his adherence to a certain code of conduct challenged and eventually defeated. In “Three Men and Adena” (March 3, 1993), an acclaimed, tension-filled episode penned by Tom Fontana and filmed almost entirely in the Box, Bayliss and Homicide 19 Figure 1.1. Bayliss and Pembleton interrogate Risley Tucker in “Three Men and Adena.” Pembleton use every possible (legal) means to illicit a confession from Risley Tucker, an elderly black street vendor, who is known as the “Arraber” and is the only suspect in Adena’s murder. In response to pressure to close the case and end his own obsession, Bayliss, in tandem with Pembleton, wages a twelve-hour interrogatory assault that makes the earlier interrogation seem like polite conversation. Both sides are firing in this verbal warfare. Tucker disparages Pembleton as “one of them five-hundreds,” after the detective tries to play on a sense of racial solidarity to coax an admission of pedophilia: “You don’t like niggers like me ‘cos of who we are, ‘cos we ain’t reached out, ‘cos we ain’t grabbed hold of that dream, not Doctor King’s dream, the WHITE dream. You hate niggers like me because you hate being a nigger. You hate who you really are.” As the deadline to release him grows nearer, Bayliss pulls the Arabber from his chair and almost uses a hot water pipe to coerce a confession. After this Tucker taunts Bayliss: “You from Baltimore, right? Do you say BAWL-mer or BALL-di-more? . . . Say Baltimore, and I’ll tell you within ten blocks where you were born. . . . You got that home grown look. The not too southern, not too northern, not on the ocean but still on the water look with maybe a touch of inbreeding.” After pushing Tucker to the brink of physical and emotional exhaustion, and getting him to confess his love for the young girl, the detectives lose their traction when the old man refuses to speak and their time runs out. In the end, Pembleton has been convinced that the Arabber is the killer, but Bayliss is no longer sure. (In season 4’s “Requiem for Adena,” it becomes clear that, in all likelihood, Tucker was not the killer.) Both Bayliss and Pembleton are changed by this interrogation—as partners and as individuals; the issues of race and class to which the Arabber refers in his barbs surface in their relationship to cases and to each other, reinforcing Homicide’s emotional realism. In “Three Men and Adena,” Bayless, Pembleton, and Tucker speak to and 20 Ba mbi L. Haggins from perspectives about race, class, and justice that are deeply rooted in their individual histories as well as the histories of Baltimore—and viewers have limited knowledge of each. Our experiences as longtime viewers of this genre are challenged: while we may always feel like we know more than we actually do—about the players, about the case, and about the city—the lack of certainty in these narratives (for the characters and for the viewers) imparts an uneasy ambiguity. As Bayliss and Pembleton confront combustible issues, the viewer is forced to do the same—with no easy epiphany. In “Colors” (April 28, 1995), the partners clash when Bayliss’s cousin shoots a drunk Turkish exchange student dressed as a member of the rock band KISS who tries to enter his house (mistakenly believing there is a party inside). Bayliss’s unquestioning acceptance of his cousin’s self-defense plea makes Pembleton question whether Bayliss can see racism in his family or on the job. This point is driven home for Bayliss when his cousin, cleared of the shooting, remarks, “Who’d have thought their blood was the same color as ours,” as he washes it off his front porch. In “Blood Ties, Part 2” (October 24, 1997), Bayliss questions Pembleton’s objectivity when a prominent black millionaire and humanitarian is embroiled in a case where the victim is a young woman who works and lives in his home and who is killed at an event honoring the patriarch. Due to the wealth of the family, their influence, and very good lawyers, no one is prosecuted, though Pembleton and Giardello know that the son is the killer and that they have been manipulated. Pembleton must admit that his judgment was colored on more than one level—by class and fame as well as race. However, the awareness of flawed perceptions, biproducts of greater social maladies, leaves issues unresolved—the characters, the narrative, and the viewer carry vestiges of these experiences. While the partnership between Pembleton and Bayliss, like those of the other detectives and the police and populace of Baltimore, dips into dysfunction as often as it reveals a kinship that is both tenuous and time-tested, we feel that their daily quest to get the “bad” guy in the Box is only part of the story. While this essay can only begin to explore the concept of “RealFeel” as a way to talk about reading television drama, the uncomfortable pleasures of watching the televisual tales of the Murder Police, whose job is never really completed (“like mowing the lawn, you always have to do it again”) and Baltimore, a not so safe space on the small screen and in “real life,” does provide an analytical mother lode. Although the sense of the “real” in emotional, intellectual, visual, and narrative terms can be difficult to quantify, in Homicide, and in most quality drama from Hill Street Blues to The Sopranos, you can see how aspects of “RealFeel” work in concert and at cross purposes. On the one hand, they conspire to synthesize backstories about culture, class, morality, and place in ways that feel comprehensible; on the other, the complexities of the narrative and the milieu Homicide 21 depicted often cause those very assumptions to be called into question. In the end, Homicide elicits the aura of realism imbricated with a sense of knowing and not knowing simultaneously—a state of ambiguity not uncommon to everyday life—which makes these Charm City stories feel enticing, unsettling, and “real.” Notes 1. See Jennifer Holt’s essay on NYPD Blue in this volume. 2. Jim Shelley, “Is Homicide: Life on the Street better than The Wire?” Guardian, March 26, 2010, 10. 3. Alice Hall, “Reading Realism: Audiences’ Evaluation of the Reality of Media Texts,” Journal of Communication 53, 4 (December 2003): 634. 4. Ien Ang, Watching Dallas: Soap Opera and the Melodramatic Imagination (London: Methuen, 1985), 45. Further Reading Hall, Alice. “Reading Realism: Audiences’ Evaluation of the Reality of Media Texts.” Journal of Communication 53, 4 (December 2003): 624–41. Lane, J. P. “The Existential Condition of Television Crime Drama.” The Journal of Popular Culture (Spring 2001): 137–51. Nichols-Pethick, Jonathan. TV Cops: The Contemporary American Television Police Drama. New York: Routledge, 2012. Simon, David. Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1991.