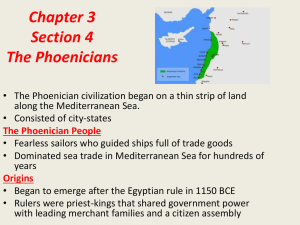

Phoenicia and the Phoenician Civilization

advertisement

Phoenicia and the Phoenician Civilization (by Fr Charbel Habchi) (Phoenician: , Canaan or Kana'an, nonstandardly, Phenicia; Greek: Φοινίκη: Phoiníkē, Latin: Phœnicia) was an ancient civilization centered in the north of ancient Canaan, with its heartland along the coastal regions of modern day Lebanon, Syria, Palestinian territories, and Israel. Phoenician civilization was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from the period of 1550 BC to 300 BC. Though ancient boundaries of such city-centered cultures fluctuated, the city of Tyre seems to have been the southernmost. Sarepta (modern day Sarafand) between Sidon and Tyre, is the most thoroughly excavated city of the Phoenician homeland. The Phoenicians often traded by means of a galley, a man-powered sailing vessel and are credited with the invention of the bireme. It is uncertain to what extent the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single ethnicity. Their civilization was organized in city-states, similar to ancient Greece. Each city-state was an independent unit politically, although they could come into conflict, be dominated by another city-state, or collaborate in leagues or alliances. Tyre and Sidon were the most powerful of the Phoenician states in the Levant, but were not as powerful as the North African ones. Map of the Phoenician territory and the important cities The Phoenicians were also the first state-level society to make extensive use of the alphabet, and the Canaanite-Phoenician alphabet is generally believed to be the ancestor of almost all modern alphabets. Phoenicians spoke the Phoenician language, which belongs to the group of Canaanite languages in the Semitic language family. Through their maritime trade, the Phoenicians spread the use of the alphabet to North Africa and Europe where it was adopted by the Greeks, who later passed it on to the Romans and Etruscans. In addition to their many inscriptions, there were a considerable number of other types of written sources left by the Phoenicians, which have not survived. Evangelical Preparation by Eusebius of Caesarea quotes extensively from Philo of Byblos and Sanchuniathon. At the Congress of Humanity which was held in Monaco in 1935, Charles Corm made the following statement. “Ever since the time of antiquity, when the Lebanese were only known by the name of Canaanites and later as the Phoenicians, they created, maintained, defended, strengthened and developed a civilization which was open and free. It contained universal values and was so accessible to other nations that some of them including the more important assimilated these values to the point of thinking they stemmed from their own genius” 1. This viewpoint seems to be well founded. It can be stated quite categorically that long before the arrival of the Canaanites to Lebanon, there already existed a kind of Lebanese civilization. Fifty thousand years before Christ, the first “homo sapiens” inhabited the Lebanese coast precisely at a place called Ksar Akil. This is near the city of Antelias which is just a few kilometers north of Beirut. Over the centuries the development of civilizations was quite rapid. Archaeologists who worked in Byblos, Sidon, Beirut and other areas had to contend with extremely difficult situations. For example one problem 1 was to ensure that the trowel of the person excavating, would reach the lowest levels or the earliest traces of the antecedents of the Phoenicians without at any time or in any way causing damage to the remains of walls, fortifications, hills, palaces which were left behind by the Persians, Greeks, Romans or Byzantines. The richness of the Lebanese subsoil is above all in the archeological treasures. They are real works of human genius. It is not our intention to study all facets of Lebanese civilization across the centuries. We will only mention the principal events and happenings which marked Phoenician-Lebanese civilization and its influence on other nations, especially those touching the Mediterranean. Maritime Expansion and Commerce: Apart from the alphabet which many consider to be the greatest invention of the world, the Phoenicians made many other important contributions to the civilizations of antiquity. They were the first nation, after the Greeks to base the development of their society on maritime expansion. During the XII to the VII centuries BC, after they had perfected the technical skills needed for navigation, they ventured out into the whole of the Mediterranean, discovering and opening up new sea routes. In this way they were able to establish commercial centers and colonies. It is due to them that a flexible association, which was held together by commerce, was able to unite all the colonies which were scattered all along the Mediterranean coast and beyond. Phoenician ship carved on the face of a sarcophagus, National Museum of Beirut Among these colonies one can mention Cyprus, Rhodes, Malta, Sicily, Marseilles, Cadiz and especially Carthage. Carthage was the daughter of Tyre and the most prestigious of all the Phoenician colonies. It eventually became a great and powerful city and as such became a threat to Rome itself. In the end Carthage waged war on Rome for control of the empire of the then civilized world. 2 Speaking of the naval superiority of the Phoenicians, Gerhard Herme has this to say: “Wherever they settled, just as in their magnificent and lavish cities situated along the coast, the Phoenicians lived more on the sea than on terra firma. Their communities would inevitably turn themselves towards the waters of the sea. In a certain manner, the land seemed to be only a base for them which they could leave at any moment in order to immerse themselves once more in their natural element. One almost has the impression that the solidity and the limitation of the land caused them a degree of uneasiness and furthermore it led them to have a certain lack of confidence in, and kind of unchanging stability. The inconstancy of the sea, its risks and its limitlessness vastness seemed to correspond more closely to the concept and understanding of life which they had, rather than to the security offered to them by a life on land” 2. Travelling much further and guided by the northern star, also known as the Phoenician star, Phoenician sailors ventured into the Atlantic, reaching the coast of Bretanha. This name is of Phoenician origin and means “land of tin” and today is known as Britain. From the British islands they imported tin and distributed it to the rest of the known world. Later, under the command of Hamilkon, a famous Phoenician admiral, they reached the Baltic coast which was rich in amber. They also rounded the coast of Africa, sailing from Gibraltar under Admiral Hannon in the year 425 BC. They succeeded in exploring the Atlantic African coast as far as Nigeria. Other Phoenician navigators went in the opposite direction and at the request of the Pharaoh Necho II, king of the Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt (610 BC - 595 BC), they sailed from the Red Sea to return via the Mediterranean. Herodotus (4.42) also reports that Necho II sent out an expedition of Phoenicians, who in three years sailed from the Red Sea around Africa back to the mouth of the Nile. The principle motivation for all these hazardous journeys was trade. The Phoenicians established an international trading system which in the initial stages, and instead of using money as a method of doing business, they were able to use barter as the mode of exchange. They traded with goods coming from Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Spain, Sicily, Cyprus, Messina, Phrygia, Greece, and North Africa as well as from many others places. They made commercial interests their priority and this provided the principal dynamo to drive the development of their civilization. The Phoenician colonies in the Mediterranean Sea According to Herbert Muller “The birth of a civilization was a technical problem, an economic enterprise inspired by practical down to earth motives” 3. Muller is quoting Whitehead who says “commerce is the origin of civilization and of liberty because it is based on negotiation and not force”. Building an empire as a private undertaking and with a spirit of adventure was the style of the Phoenicians and it still continues to be the style of the Lebanese to this day. In this way as Dunand adds: “Phoenicia succeeded in becoming far greater than she actually was” 4. It was well said of the Phoenicians that they “brought the alphabet on their lips, coins in their fingers and the breath of civilization in the lamps of their ships”. Martial Phoenician ship stamped on an old coin in Tyre 3 The Phoenician Trade The Phoenicians were amongst the greatest traders of their time and owed a great deal of their prosperity to trade. The Phoenicians' initial trading partners were the Greeks, with whom they used to trade wood, slaves, glass and a Tyrian purple powder. This powder was used by the Greek elite to color clothes and other garments and was not available anywhere else. Without trade with the Greeks they would not be known as Phoenicians, as the word for Phoenician is derived from the Ancient Greek word phoinikèia meaning "purple". Tyrian coin with bilingual inscription Greek-Phoenician In the centuries following 1200 BC, the Phoenicians formed the major naval and trading power of the region. Phoenician trade was founded on Tyrian purple, a violet-purple dye derived from the Murex seasnail's shell, once profusely available in coastal waters of the eastern Mediterranean Sea but exploited to local extinction. James B. Pritchard's excavations at Sarepta in present day Lebanon revealed crushed Murex shells and pottery containers stained with the dye that was being produced at the site. The Phoenicians established a second production center for the purple dye in Mogador, in present day Morocco. Brilliant textiles were a part of Phoenician wealth, and Phoenician glass was another export ware. From elsewhere they obtained other materials, perhaps the most important being silver from Iberian Peninsula and tin from Great Britain, the latter of which when smelted with copper (from Cyprus) created the durable metal alloy bronze. Strabo states that there was a highly lucrative Phoenician trade with Britain for tin. The Phoenicians established commercial outposts throughout the Mediterranean, the most strategically important being Carthage in North Africa, directly across the narrow straits in Sicily and the island of Malta in the center of the Mediterranean; carefully selected with the design of monopolizing the Mediterranean trade beyond that point and keeping their rivals from passing through. Other colonies were planted in Cyprus, Corsica, Sardinia, the Iberian Peninsula, and elsewhere. They also founded innumerable small outposts a day's sail away from each other all along the North African coast on the route to Iberia's mineral wealth. Painting of a Phoenician galley The date when several of these cities were founded has been very controversial. Greek sources put the foundation of many cities at a very early date. Gades (Cadiz) in Spain was traditionally founded in 1110 BC, while Utica in Africa was supposedly founded in 1101 BC. However, no archaeological remains have been dated to such a remote era. The traditional dates may reflect the establishment of rudimentary stations that left little archaeological trace, and only grew into full cities centuries later (The World of the Phoenicians, Sabatino Moscati, 1965). Alternatively, the early dates may reflect Greek historians' belief that the legends of Troy (mentioning these cities) were historically reliable. Phoenician ships used to ply the coast of southern Spain and along the coast of Portugal. It is often mentioned that Phoenicians ventured north into the Atlantic ocean as far as Great Britain, where the tin mines in what is now Cornwall provided them with tin, although no archaeological evidence supports this belief and reliable academic authors see this belief as hollow (see Malcolm Todd - 1987, reference below). 4 However, ancient Gaelic mythologies of origin attribute a Phoenician/Scythian influx to Ireland by a leader called Fenius Farsa. Others also sailed south along the coast of Africa. A Carthaginian expedition led by Hanno the Navigator explored and colonized the Atlantic coast of Africa as far as the Gulf of Guinea; and according to Herodotus, a Phoenician expedition sent down the Red Sea by Pharaoh Necho II of Egypt (c. 600 BC) even circumnavigated Africa and returned through the Pillars of Hercules in three years. The Phoenicians were not an agricultural people, because most of the land was not arable; therefore, they focused on commerce and trading instead. They did, however, raise sheep and sell them and their wool. The center of human relations While being the centre of commercial exchange in antiquity, Phoenicia was also one of the great centers of human and cultural relations. Continually in contact with practically the whole world and open to all cultural and religious movements without allowing themselves to be side tracked from their own specific culture and traditions, the Phoenicians were the architects of a civilization and a particular style of living that can be termed ecumenical and universal. It was a style of civilization which inspired the Greeks. Our civilization is credited with some of the most beautiful works and cultural accomplishments that the world has ever seen. Statue of god EL, limestone, Ugarit In an age in which every city paid homage to a number of indigenous gods, often very cruel and blood-thirsty, the Phoenicians had reached a stage in their religious beliefs where they recognized only one universal god, a god of love and mercy and the enemy of violence. It was the god EL, reverenced by all throughout every region of Phoenicia as the allpowerful one and origin of life and creation. The Roots of Ancient Civilizations The Phoenician civilization was a veritable symbol and example for the other nations of the East. Take the Egyptian civilization for example. It is so rich and ancient but it has its roots deep in Phoenicia. This is evident from the presence of numerous Phoenician legends in the mythology of Egypt. It is also evident from the particular devotion the Pharaohs had for the god Baal in Byblos. They regularly sent votive offerings and precious gifts to the temple there 5. The same influence took place with the Greeks. In effect, before Phoenicia was hellenized by Alexander the Great, Greece herself had been influenced by the Phoenicians. Legends and history support this fact. For example, the epic poetry of Ugarit prepared the way for the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer; Aristotle and Plato had as predecessors Xenon and Pythagoras, both of whom were Phoenician philosophers. G. MASPERO, History of Egypt, vol. VI. 5 Many historians seem to forget that a large number of the more outstanding examples of Greek culture were of Phoenician origin or were touched by Phoenician culture. Among them: Thales, the great mathematician and father of Philosophy 6; Xenon, the founder of the Stoic School; Euclid, the father of Geometry 7; Pindar, the composer of the “Odes”; Porfirio, the founder of the Neo-platonic School 8; Mokhos, who 3200 years ago maintained that the atom could be divided, and this was against all established theories at that time 9. Even the Olympic Games, which the whole world thinks was a Greek invention, had their origin in Phoenicia. Recent archeological discoveries demonstrate that the Sports Stadium of Amrit and Sidon existed already before the Olympic Games and were for the same purpose. The “Olympic” games in the Phoenician stadia were linked to the temples and entered Greece in the XVI century BC together with the Phoenician culture and mythology 10. Skills and a sense of democracy Other forms of Phoenician civilization appear in the area of their workmanship. The world knew of the use of purple exclusively from doing trade with the Phoenicians. Purple is a dye that is extracted from shellfish and for centuries the Phoenicians kept the method of its manufacture a closely guarded secret. They also perfected the technique of manufacturing luxury items such as perfumes, jewelry, glass objects and household furniture inlaid with metal such as gold and ivory. Glass was invented by them in the initial stages of their development. It was a person from Sidon who invented the process of “blowing glass” and this process spread to all other parts of the world in no time. Luxury Phoenician glass items It is not often remembered that one of the most precious contributions of the Phoenicians to civilization was the sense of democracy and respect for the individual. This has been assumed to have originated within Greek culture. The truth is that the outline of the Greek “polis” - the Greek city - with its juridical concept of the social body was first delineated in Phoenician society, the society with the least imperial intentions and one closest to the aspirations of the people. The small extent of their land mass of Phoenicia favored the development of a sense of proportion and limits which shows a real grasp of the concept of political space. At another level, the ancient east was continually inclined towards a political model of despots with absolute power. Kings and emperors were obeyed and considered as “sons” or representatives of gods. On the contrary in Phoenicia there were assemblies who participated with the monarchy or the government and they often took decisions contrary to its wishes. In a sense the Phoenicians created the first republics, governed by elected magistrates or judges. This democratic regime in the Phoenician cities brought the Phoenician world to a new level of life style, progress and national development. The empires and cities in those far off times were regularly at war with each other. Each country wanted to impose its rule on its weaker neighbors. History bears witness to the truth that the city-states of Phoenicia never warred among themselves. They were aware that they were the same people and they formed a system of federation to which they all subscribed. They looked to Tripoli as their capital. In Tripoli each of the greater city-states had its own suburb in which their representatives or delegates resided. These formed a kind of Supreme Court where they discussed all the issues of common interest, especially those which pertained to external affairs and the attitude they should adopt when they faced a danger from outside their borders. 6 Phoenician divine figurines from the temple of Obelisques in Byblos In regards to danger from abroad, the Phoenician policy was always to negotiate with the enemy. They were prepared to cede what they knew they could do without in order to hold on to what was essential to protect their independence. This they negotiated through diplomatic channels and not by force of arms. In this way for example the Phoenicians were the allies of Egypt and not their subjects, nor vassals of the Pharaoh. This was the strategy by which they were able to preserve their independence under the Assyrian Empire, the Babylonian Empire and the Persian Empire. They succeeded in safeguarding their own identity, refusing to allow themselves to be absorbed and dissolved into a vaster and very different nation. Valiant in combat Sometimes the demands of those making claims on the political leadership were so extreme that they were incompatible with the dignity of the Phoenician. It was then that a struggle together with obstinate resistance would take place which at times led to destruction and death. But destruction and death are always followed by a resurrection and rebirth and this is always a basis for a new start and a new beginning. 7 It is worthwhile to recall the case of Sidon where the inhabitants preferred death in battle to capitulating to the Assyrian Esarhaddon in 677 BC. Much the same happened against the king of Persia, Artaxerxes in the V century. There is also the case of Tyre which survived a blockade of 13 years against the Babylonian king Nabuchodonozor II. Alexander the Great succeeded in bringing the city of Tyre into submission but only after he had laid siege to it for ten months. Finally there is the case of Carthage whose population preferred to die with the city rather than submit to the rule of Rome. The Phoenician people always showed themselves more generous and braver than their governors in times of national crisis. In Sidon as in Tyre and in Carthage, it was the common people in their heroism who were prepared to fight even to the point of death to preserve and safeguard their national dignity. Their leaders meanwhile sought by means of compromise to save their own necks, their positions of status and power and their wealth. In this regard history repeats itself so often. According to Donald Harden, the bravery of the Phoenicians of Lebanon as valiant warriors in battle “was demonstrated, not only in their prolonged and exhausting struggle with Rome, but also in the resistance with which Tyre and Sidon opposed the Mesopotamians and other conquerors 11. Perpetuating the Civilizing Influence During the epoch of the Assyrian-Babylonian the two civilizations of Mesopotamia and Phoenicia had occasion to work together and be mutually influenced by one another. The coastal cities of Phoenicia succeeded in holding on to their important civilizing role. These cities continued as centers of industry, wealth and culture. The Phoenician tradesmen, always quick to take advantage of any opportunity which presented itself for business, developed and expanded their civilization and contributed greatly in this way to the civilization of the world in spite of the numerous revolutions and changes of governors which took place. Martial Phoenician ship stamped on an old coin in Tyre As owners of the largest and best equipped fleet the Phoenicians aided the martial undertaking of the Persians. The Phoenician ships were offered voluntarily for the conquests managed by the Cambyses, the Persian kings. But when the Persians requested the help of the Phoenician fleet in order to attack Carthage, the “daughter” of Tyre, they refused. Phoenicia lost its independence when Alexander the Great conquered Tyre in 333 BC. This was the first time that strangers were able to reign and have complete control of these indomitable people. But the Greeks and the Phoenicians had much in common to share on the level of human values in spite of the intoxication of victory on one side and the bitterness of defeat on the other. It became a great time for the expansion of one common civilization of the two nations as the political eclipse of Persia brought a strong Hellenistic influence to Phoenicia. Phoenician ship carved on rock, Harbor of Tyre. Many years later when Phoenicia was completely immersed in the Roman world and became part of the Roman ecumenical civilization, the Phoenician people offered the Romans a new style of architecture and a new spirit. Lebanon managed to raise itself to a very high level on terms of material prosperity, spirituality 8 and culture. This was due in part to religious, political and cultural factors among others. The wisdom of Rome, creator of peace, order and discipline, favored the contact between the two nations as well as all the activities which were favorable to progress. With reference to Phoenicia, this Roman approach encouraged the Phoenician enterprising spirit to reach new heights of civilization and a prodigious advancement in all aspects of life. Its plains were turned into the granary of the Roman Empire. Beirut became the “Mother of Laws” with the establishment of a School of Laws. Other cities such as Tyre and Sidon became industrial, commercial, religious and cultural centers for the whole of the Roman Empire. Baalbek gave to the world one of the greatest monuments ever constructed by man. The most lyrical poem which could ever be composed to describe and praise the monuments of Baalbek could not do justice to its stature. One can only hide away in the presence of this majestic edifice and only silence can echo its grandeur. Never has stone felt the urge to raise itself higher towards the sun than at Baalbek. Never has the human spirit been so urged by a holy desire to dream and bring into existence so grandiose a project. The temples of Byblos, Ugarit, Rome and Athens, even in the time of their greatest splendid, pale in comparison. They did not attain the magnificence which Baalbek had during the first centuries of Christianity, Even after the wars and demolitions which took place later, Baalbek remained a “spectacle of what is possible, a brilliant demonstration of the virtuosity of the architects who drew their plans and oversaw to their execution 12. In general historians claim that the monuments of Baalbek were built by the Romans because they became so well known during the Roman occupancy. But this view has no response to the question posed by many other archaeologists and historians namely: Why did the Romans erect temples in Phoenicia greater than those in Rome and with decorations more costly and with art more refined? Some ruins of the monuments of Baalbek This question, based on a common feeling can be reinforced by scientific arguments which lead some historians such as Auguste Choisy, Haroutone Kalayan, Lina Murr Nehme to affirm that Baalbek is a monument more Phoenician than Roman. The proofs offered by Lina Murr Nehme in her work “Baalbek, Phoenician Monument” seem to us of great value and should be taken seriously 13. These are some of her proofs: The date of the completion of the gigantic sanctuary of Baalbek (dated 60 of the Christian era according to an inscription on one of the columns) excludes any Roman participation 14. The size of the stones of Baalbek and the type of architecture are Phoenician. Some of the blocks of stone are up to 1000 tons in weight. The historian Hilaire Belloc says that only the Phoenicians were capable of utilizing stones so great in the construction of temples and other monuments 15. 16 The tools used in the construction of Baalbek were Phoenician 17 The plan of the temple of Baalbek is Phoenician . It is the plan and its proportions which demonstrate its origin, not the decoration. 9 The temples of Baalbek have enormous altars and reservoirs of water for ablutions in the great patio. These are two Phoenician traditions 18. The temple of Baalbek has a patio in hexagonal form. Neither the Greeks nor Romans used the hexagonal form in architecture 19. No emperor has ever claimed the construction of Baalbek. The traveler Constantin Volney expressed his amazement about this fact which was so different to the normal mentality and attitude of Roman emperors 20 . The geographical location of Baalbek proves the impossibility of the Roman’s building such a monumental edifice so far from Rome itself. The Romans were a most proud people. They would never have agreed to the emperor using money from the state coffers to finance such a grandiose and costly monument in a foreign land. In addition the legacy which Rome left to humanity (The Roman Right) is not as Roman as one is led to think. In greater part it is the product of Phoenician philosophy stemming from the famous School of Laws of Beirut. In no other period did eastern influence manifest itself so clearly in the question of the Roman Right, than during the reigns of the emperors whose origins were Phoenicians. The emperor Severus granted the right of citizenship to all the inhabitants of the empire. Every person of this vast empire was then able to share in the benefits of the right which up to that time had been reserved only to the citizens of Rome and its suburbs. Monuments of Baalbek It was a classic time, a high point in history, a time in which the Right was taught in the school of Beirut. The “Mother of Laws” was steeped in justice and in the rights of oriental peoples, thanks to the Phoenicians jurists, Aemilius Papinianus (142-212), who was their leader, and Paulus and Domitius Ulpianus (170-228) from Tyre, whose opinion had the force of law for the judges. These jurists who occupied a very high position in the Office of the Presidium, that is, the Office of the Supreme Judge of the Empire were as famous for the independence of their character as for the nobility of their spirit 21. The works of these famous jurists were made into a collection by the emperor Theodosius and incorporated into the “Institutes of Justinian”. Years later another jurist, Anatolio from Beirut, published a commentary on the “Code of Justinian”. Parallel with the Legal School in Beirut there was another school there at the same time which was in competition with it on an intellectual level. This school was under the direction of Libanus, a famous rhetorician. His methodology and the content of his lessons revolutionized education. Nonnus, in his praise for Beirut says: “To put an end to discord and to let peace reign among men, it is necessary for Beirut to 10 govern the world with her laws”. It is true to say that Phoenicia contributed as much to the culture and civilization of both the Greeks and Romans as she received from them 22. BERYTUS NUTRIX LEGUM BEIRUT MOTHER OF LAWS From the IV century AD, Byzantine, who took over the eastern part of the Roman Empire, was gradually weakened by a series of internal conflicts over politics and religion. In spite of this, Phoenicia continued with her own historical and cultural mission of enriching the Byzantine world with architectural and decorative buildings. Phoenicia continued to develop and make progress in her own way, until at length she was reckoned to be the richest province in the Byzantine Empire. Wars and invasions notwithstanding Phoenicia succeeded in safeguarding her uniqueness. Even better, when invaders came into contact with Phoenicia they began to modify their behavior to the point that they began to adopt in whole or in part the manners and the customs of the Phoenicians. They acquired navigation skills, business skills as well as craft, art and literacy skills. A Phoenician ivory plaque showing the goddess Ishtar & Ornaments worn by women of Phoenicia 11 References: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. CORM Charles, 6000 anos de gênio pacifico ao serviço da humanidade, Belo horizonte 1974, p. 7. HERM Gerard, A civilização dos Fenícios, São Paulo 1979, p. 16. MULLER Herbert, the Uses of the Past, p. 50. DUNAND M., art. Phénicie, in Dictionnaire de la Bible, supplément, t, IV. DUNAND M BYBLOS, Byblia Grammata, op. cit. p.63-64. AMMOUN Fouad, Le legs des Phéniciens à la Philosophie, Beyrouth 1983. P. 11-14. Ibidem, p. 201-203. Ibidem, p. 360-361. Ibidem, p. 72-73. BOUTROS Labib, The Phoenician Sport and his influence on the elaboration of the Olympic Games, Beirut 1974. HARDEN, op. cit. p. 18. PARROT André, Les Phéniciens, Paris 1975, p. 18. NEHME Lina, Baalbek monument phénicien, Beyrouth 1997, p. 61-87. Kalayan H., The Story of the Building process of the Temple of Jupiter and of its Courtyards. PERROT et CHIPIEZ, Histoire de l’Art dans l’Antiquité, t. III, La Phénicie et ses dépendances, p. 101-105. KALAYAN, op. cit. p. 106. Ibidem, p. 107. COLLART Paul et COUPEL Pierre, L’Autel Monumental de Baalbek, Beyrouth 1951. NEME Line, op. cit., p.78. VOLNEY Constantin, Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie, Paris 1959, p. 312. EDDÉ Camille, La civilisation méditerranéenne et le droit en Syrie, Le Caire 1921, p. 7. AMMOUN Fouad, op. cit., p. 268 -272; p. 282-301. 12