History of Intervention with DV Perpetrators

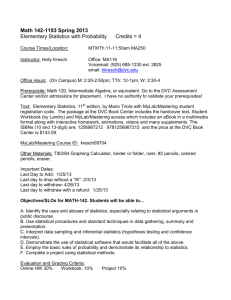

advertisement

HISTORY OF INTERVENTION WITH DV PERPETRATORS Katreena Scott, Ph.D. C. Psych. University of Toronto MAGNITUDE OF THE PROBLEM Family violence accounts for 33% of violent crime reported to police 30% homicides committed against females are perpetrated by intimates Intimate partners perpetrate 23% of self -reported non-fatal violent crime victimization (rape, assault, aggravated assault) against females 28% of substantiated child protection investigations are due to child exposure to domestic violence WHERE WE ARE GOING Mandatory arrest Making charges stick: DV Court Court-linked intervention programs: Partner Assault Response (PAR) Risk Assessment and Risk Management HOW DID WE GET MANDATORY ARREST Early to mid 1970’s General police practice was to separate for a “cool down” period Not for some! Us social science people had already started to try to mettle/collaborate and some police departments had just undergone pretty extensive training in mediation In some jurisdictions, aim was for mediation to reduce rates of arrest (advantages of crisis intervention) WOMEN NEEDS FOR SAFET Y WERE RECOGNIZED (MID TO LATE 1970’S) Key messages It could happen to any woman Perpetrators (predominantly men) were the problem, not those experiencing the abuse (this was not a problem related to the victim’s personality) Consequences are serious and potentially long -term Society needs to change to protect women at risk Organization of shelters In the late 1970’s and early 80’s, began to advocate for a dif ferent justice response BERK AND SHERMAN’S EXPERIMENT American Sociological Review, Vol. 49, No. 2 (Apr., 1984), Police Foundation and the Minneapolis Police Department Field experiment on domestic violence . arrest advice (including, in some cases, informal mediation ) an order to the suspect to leave for eight hours Six month follow -up af ter police intervention of of ficial data and victim reports RESULTS Condition Police Data, assault Arrest 13% Separate 26% Condition Victim Report, assault Arrest 9% Advise 37% There was very little incapacitation REPLICATIONS Minneapolis experiment replicated in six other cities. Meta-analysis by Sherman in 1992 concluded that replications did not produce results as conclusively favouring mandatory arrest as the original experiment Some evidence of dif ferential impact Stake in conformity (unmarried, unemployed, previously arrested) Procedural justice MAYBE ARREST IS NOT ENOUGH MID 1990’S: RISE OF THE DV COURT In 1997, the Domestic Violence Court (DVC) Program began in 6 Ontario communities Expanded fairly rapidly to all jurisdictions by the mid 2000’s Like other specialized courts, DVC aims to: Increase efficiency in processing cases Lessen the impact of crime by providing services to victims (V/WAP) Ensure that Crowns and Judges hearing these cases were trained in the area Hold offenders accountable, associated intervention, carrot and stick method of justice EVALUATION OF DVC PRA Report to the Ministry of the Attorney General, 2006 Some highlights Consistent evidence that the V/WAP through DVC improved the provision of information and other services to victims Increase in use of risk assessments Increase in collection of evidence in addition to victim testimony (e.g. 911 calls) 36% of offenders receive PAR as a condition of probation; other counselling ordered more frequently (55%) Most men (91%) received probation (sometimes as well as incarceration) Probation conditions increased with DVC program, in particular non association orders, no weapons and other counselling EVALUATION OF DVC Average time from of fense date to guilty plea was 126 days For of fenders who did not enter the EIP, the average number of days from of fense to was 159 days Wait times tended to be longer in larger urban centres, especially Toronto EVALUATION OF DVC DVC cases more likely to result in a plea or finding of guilt (66%) as compared to all charges (52%) A lower proportion of DVC cases have the most serious charge withdrawn or stayed as compared to general category of criminal cases (24% vs. 44%) IMPROVEMENTS STILL NEEDED Identified substantial problems with the IEP program in terms of what kind of cases were making it into the program Identified problems with referral to PAR and with follow -up around this Problem with communication among members of the system Problem with inconsistency between criminal court and family court orders We can list others OUTCOMES WITH AND WITHOUT DVC Recidivism of 500 men convicted in 2001 through DVC or non DVC (DOJ evaluation) Recidivism defined as at least one reconviction for any criminal of fense between index of fense and Dec 31 , 2003 (approx. 2 yrs.) 31% DVC and 32% non-DVC men were reconvicted WHAT IF WE ADD TREATMENT? BATTERER INTERVENTION PROGRAMS In the late 1970’s a few program for men were stated including Emerge in Boston, RAVEN in St. Louis, AMEND in Denver, Manalive in Marin County California, the Domestic Assault Program in Tacoma Washington, and Men Stopping Violence in Atlanta These programs used a variety of models of intervention In 1981 , a group of individuals in Duluth, Minnesota including Ellen Pence and Michael Paymar established the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, the Duluth Model (26 weekly group sessions) BATTERER INTERVENTION PROGRAMS Duluth most natural extension of the justice intervention Primary mission is to promote safety for victims and accountability for batterers Education about DV, help reduce minimization and denial, promote accountability To a greater or lesser extent, teaching of relationship, communication, emotion-regulation skills so that abusive behaviour is more easily avoided HOW EFFECTIVE IS BATTERER INTERVENTION? Quasi-experimental studies (i.e., compare outcomes of men who completed the group to those who did not) generally find a significant moderate ef fect of intervention (e.g. 20% dif ference in re-assault rates) Experimental studies (again six funded by the DOJ in the US) find minimal impact of intervention for men randomly assigned to groups Lots of problems with random assignment What about dose, is it fair to consider someone who attended one session as having completed the program? Low response rate from women WHERE WE ARE NOW Cochrane Collaboration, by Smedslund G, Dalsbø TK, Steiro A , Winsvold A , Clench-Aas J, 2007 “The research evidence is insuf ficient to draw conclusions about the ef fectiveness of cognitive behavioural interventions for physically abusive men in reducing or eliminating male violence against female partners. This does not mean that there is evidence for no ef fect. We simply do not know whether the interventions help , whether they have no ef fect, or whether they are harmful .” BUT WE HAVE LEARNED A LOT! WE CAN SHOW CHANGE… In attitudes towards partner In level of minimization In communication skills In anger regulation In knowledge of the definition of abuse and of abuse supporting cognitions But, it is dif ficult to establish that any of these changes are associated with reductions in reassault RESULTS FROM 10 ONTARIO PAR PROGRAMS 2.5 2 1.5 1 Disavowal of responsibility Partner blame Pre-program Denial Post-program FREQUENCY OF REPEAT ASSAULT EFFECTS OVER TIME IMPACT OF DROPOUT Program completion is associated a 44% reduction in the likelihood of partner-reported re-assault, from a recidivism rate of 55% for program dropouts to a recidivism rate of 36% for program completers (Gondolf, 2002) Similar results were reported by Bennett et al. (2007) in their analysis of 899 men referred to 30 dif ferent BIP programs. These researchers found that program completion was associated with a 39% reduction in the likelihood of reassault. PREDICTORS OF REASSAULT History of violent arrests Continued, problematic use of alcohol and/or drugs Failure to complete treatment Any new charges Severe psychopathology (some controversy) Women’s perception of danger (not onetime assault but multiple) *some overlap with standard risk assessment measures, Gondolf’s analysis found no additional advantage once these variables accounted for SUMMARY SO FAR Arrest alone can be helpful for men who have a high stake in conformity and/or who have a strong sense of procedural justice DVC courts help ensure the justice process moves smoothly, but may not alter rates of recidivism rates Intervention helps to promote change among those who complete the program. Drop -out itself is a good indicator of risk. WHERE WE ARE NOW: RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT Now we can identify the higher risk of fenders Let’s see what we can do with them, our 33% reassaulters or especially our 15 to 20% multiple reassaulters Most likely to dropout of intervention Most likely to have previous charges for a range of offenses and be judged as moderate or high risk Most likely to reoffend quickly and to cause injury More likely to have complicating additions problems More likely to have a lower stake in conformity DIFFERENTIAL RESPONSE BASED ON LEVEL OF RISK Risk assessment is now a routine part of service in many areas, and it is becoming more ubiquitous Use of risk assessment as part of intervention for women is fairly common Agreement that risk assessment without risk management is not helpful Working to pull together teams to make sure that high risk men don’t slip through the cracks We are trying to facilitate access to safety for high risk women All of these things make sense and should be continued BUT WHAT DO WE DO WITH THE MEN? Increase criminal sanctions Is there another option? THINKING ABOUT RISK ASSESSMENT We do know that risk assessment instruments like the B SAFER and ODARA are reliable and valid We don’t know if use of these instruments by probation or cour ts is related to reductions in recidivism We do know that many women have completed the Danger Assessment We know ver y little about how this impacts her decision making around safety We do know that services to men are increasingly being organized by the level of risk he presents We don’t know anything about sharing this risk information with offenders HEALTH BELIEF MODEL WHAT IF WE STARTED TALKING TO MEN? Specifically, what if we started talking to men about their level of risk to re -assault their partner? Or specifically, to perpetrate a lethal assault? What if we raised their perceived susceptibility? What if assessed their sense of the severity of the consequences? What if we started talking to men directly about specific preventative actions and addressed perceived benefits and barriers? WHAT IF WE LINKED THIS TO WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW ABOUT INTERVENTION? Longer, more intense treatment Some evidence from the criminal justice system on risk, needs, responsivity Growing evidence and skill in providing cognitive -behavioural therapy Impact of engagement Evidence that we are more successful when we “meet men where they are at” INTERVENTION WITH HIGHLY RESISTANT CLIENTS Significant and substantial difference in rates of program completion (Scott et al., 2011) Intervention Type % Complete Motivation Enhancement 82% Standard Programming 47% Effects maintained when other significant predictors of program completion were included. Men assigned to motivation enhancing intervention were still three and a half times more likely to complete then men assigned to standard programming Results echoed in studies by studies done by other researchers: Scott & Wolfe (2003); Taft, Murphy, King, Musser & DeDeyn (2003); Taft et al., (2001); Woodin, Rosenbaum, Taft, Murphy, Musser, et al. (2008) 38 STAY TUNED… Would risk discussions for DV work similarly to risk discussions about heart attacks?