Canto VII in the Inferno

advertisement

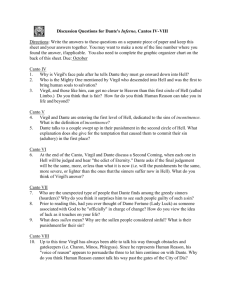

Johnson 1 Charles W. Johnson AP English 12 20 August 1998 Canto VII in the Inferno Dante’s Inferno remains one of the most haunting and most influential works in the Western canon, despite the more than six and a half centuries since its creation. The vision of Hell crafted by Dante has inspired countless thinkers and writers, from theologians and moralists to horror writers. It is admired for its elegant lyricism, its vivid and horrible imagery, and the lasting themes of its reflection on moral debasement and the spiritual journey. Canto VII, which describes the torment of the miserly, the prodigal, the wrathful, and the slothful, exemplifies many of the overarching elements of the work as a whole. Throughout the Inferno, triads are reflected in the structure of the work. The introductory canto is followed by thirty-three cantos of the story. The complex rhyme scheme of the poem, terza rima, is based on triple rhymes and stanzas of three lines. This obsession with triples is also reflected in the narrative structure of canto VII. The Pilgrim sees three primary sights: clucking Plutus, the abusers of wealth, and the Styx. Three punishments are described: eternal rolling of the burden, wrathful grappling, and being buried beneath the slime of the Styx. The repetition of triples in canto VII and throughout the work helps establish the formal elegance so often admired in Dante’s verse. The presentation of Hell often interweaves the ghastly sights with abstract philosophical reflections, as Dante’s guide (representing human Reason) explains the meaning of the lurid details. In the previous canto, Virgil explains the fate of the damned; in canto VII, he muses on the ever-changing cycle of Fortune, who gives and takes the wealth and power of the world. The Johnson 2 break from narrative into abstract discourse is done swiftly and elegantly, as the philosophical tangent reinforces the more direct lesson of the tormented souls before us. A common creature seen throughout the Inferno is the demonic agent, a role filled by Plutus in canto VII. Hellish beasts appear throughout the Inferno as the temptation of each sin threatens to end the Pilgrim’s journey to enlightenment. The beasts appearing in each circle stand as representatives of their respective sins. The bestial Cerberus is the symbol of the Gluttons. The brutish Centaurs represent the Violent. And Plutus, the god of wealth, stands as the mascot of the circle devoted to the lovers of money. Although he waylays Dante for a moment, as with all the other demonic creatures, he must ultimately fall before the will of Heaven and allow the Pilgrim’s journey to continue. The Guide (Reason) forcefully commands Plutus (the apparition of sin; a barrier on the Pilgrim’s spiritual journey) to step aside, and the clucking god simply collapses into nothingness. The rigid structure of the verse, the steady progression of the narrative, and the ordered arrangement of each circle combine to create the theme not of a wild Hell dominated by Satan, but rather a controlled and orderly Hell brought about by exacting Divine Justice. Canto VII helps build this impression; even its teeming mass of abusers of wealth still move in an orderly circle and follow the same repeating pattern into eternity. This ordered Hell of Dante’s is divided into three large sections, each for one of the broadest categories of sin, and the fourth and fifth circles are in the first, where those who failed in self-control are punished. The misers and prodigals “had such myopic minds they could not judge with moderation when it came to spending” (38). The wrathful and slothful allowed their base instincts of rage and procrastination to overcome their virtue. Punishment is carefully doled out to each of the three classes of sinners, each with its own form of torment meticulously matched to its spiritual failure. Johnson 3 This leads into one of the ubiquitous themes in Dante’s work: contrapasso, or torment of a sin by reflecting it in the punishment. In canto VII the theme is shown several times, most elaborately with the abusers of wealth. The hoarders and wasters of the fourth circle are doomed to eternally push great weights in circles, for trying to defy the great Wheel of Fortune. They must shove against each other, eventually reversing their position and completing the cycle of wealth and poverty against which they had rebelled in life. “Her changing changes never take a rest; necessity keeps her in constant motion” (39), and this is mirrored in the sinners’ unrelenting task of pushing their burdens, summed up in the ironic, haunting lines: “for all the gold that is or ever was/beneath the moon won’t buy a moment’s rest/for even one among these weary souls” (39). More examples of reversal make themselves clear. The wrathful of the fifth circle tear eternally at one another in rage. The slothful, condemned to the same swamp, are immersed in filth. Their idle dallying has led them to be buried in the sluggish muck of the Styx. Like many other places in the piece, canto VII makes use of Dante’s fertile sensory imagination. The marching circle of hoarders and wasters is compared to the seething currents of a whirlpool. As in many other parts of Dante’s Hell, the sense of hopelessness is conveyed in the imagery of the scenery: the Styx is dingy, grey, murky. Its swampiness is repeated again and again: muddy, slimy, bogged, sluggish, muck. The wailing despair of the sinners is conveyed with the clashing and screaming of the miserly and prodigal, as they cry out “Why hoard?” and “Why waste?” The structure, themes, and imagery of the Inferno mesh to create a unique tapestry which captivates us both in its timeless abstract reflections and in the horrifying concretes that are brought to life as the manifest form of philosophical principles. Each damned shade has behind it a profound question of morality and spirituality. In canto VII many of these key elements are Johnson 4 exemplified, from the fleshy imagery, to the eloquent and orderly structure, to the moral and spiritual themes. This interaction brings together a captivating whole, a work which may always remain one of the most influential works of European literature. Johnson 5 Works Cited Alighieri, Dante. Inferno from The Portable Dante. Translated by Mark Musa. Penguin: New York. 1995.