A 16-Year-Old Girl with Chronic Intermittent Abdominal Pain

advertisement

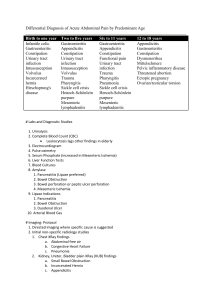

Case Challenge Radiology A 16-Year-Old Girl with Chronic Intermittent Abdominal Pain Bheesham D. Dayal, BSc; and Nida Blankas-Hernaez, MD, FAAP A previously healthy 16-yearold girl was admitted to the emergency room and ultimately to the hospital floor with a 1-day history of severe abdominal pain. Her past medical history consisted of intermittent abdominal pain for 6 years without any identifiable cause. She had no changes in bowel habits or history of abdominal surgery, and her family history was negative for any gastrointestinal diseases. Two days before presentation, she presented to our office with dysuria and lower abdominal pain, and sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim was begun after urinalysis and urine culture were performed. The urinalysis showed a trace of Bheesham D. Dayal, BSc is a fourth-year medi- cal student at Windsor University School of Medicine, St. Kitts and Nevis, West Indies. Nida BlankasHernaez, MD, FAAP, is an Associate Professor with the Department of Pediatrics, Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, IL. Address correspondence to: Nida BlankasHernaez, MD; fax: 847-972-1926; email: beeshamd@aol.com. Mr. Dayal and Dr. Blankas-Hernaez have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20111209-03 blood, but was otherwise normal. The culture ultimately was negative. The patient’s symptoms improved at first, but 1 day after she started taking the antibiotics, she developed severe abdominal pain and vomiting. She went to the emergency department, where intravenous fluids were administered along with an antiemetic (ondansetron). On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were as follows: temperature 97.8°F, pulse 86/min, blood pressure 115/77 mm Hg, and respiratory rate 24 breaths/ min. She was a normally developed girl who appeared uncomfortable but was in no acute distress. Her abdomen was soft without distention, and she exhibited no peritoneal signs. Normal bowel sounds were auscultated. There was notable tenderness to palpation, especially over the epigastrium, the left periumbilical area, and her left and right flanks. In addition, there was also mild tenderness over McBurney’s point, but obturator, psoas, Murphy, and Rovsing signs were all negative. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable. Her rectal examination was normal and pregnancy test was negative. Hemoglobin, white blood Figure 1. Upper gastrointestinal contrast study confirms the diagnosis of malrotation as the small bowel (SB) is found to be located entirely in the patient’s right abdomen, while the colon is located in the left abdomen, and the cecum (C) is seen in the left lower quadrant. Source: Dayal B, Blankas-Hernaez N. Reprinted with permission. cell count, and basic chemistry panel were all within normal values. Urinalysis showed negative nitrates and leukocyte esterase; however, there were a few bacteria present with one to five squamous epithelial cells; one to five WBC; and one to two red cells. For her presumed urinary tract infection, the antibiotic was continued. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast and upper GI with contrast (see Figure 1) were obtained and revealed the diagnosis. For diagnosis, see page 10. Editor’s note: Each month, Case Challenge features a discussion of an unusual diagnosis. A description and images are presented, followed by the diagnosis and an explanation of how the diagnosis was determined. Your comments are welcome via email at editor@pediatricsupersite.com. To submit a case, visit: www.PediatricSuperSite.com/Submit. PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:1 | JANUARY 2012 4101CaseChallenges.indd 9 www.PediatricSuperSite.com | 9 12/30/2011 12:16:55 PM Case Challenge Diagnosis: Intestinal Malrotation The abdominal CT scan and upper GI showed malpositioning of her small bowel, which was located almost entirely on the right side of the abdomen. In addition, the orientation of the superior mesenteric vessels was abnormal (Figure 2), which was highly suggestive for malrotation of the bowel without evidence of volvulus. The patient was then admitted and managed with nasogastric tube decompression and intravenous hydration. An upper gastrointestinal contrast study confirmed the suspected diagnosis of intestinal malrotation. It showed the small bowel located entirely in the right abdomen, the colon located in the left abdomen, and the cecum in the left lower quadrant (Figure 1, see page 9). DISCUSSION Intestinal malrotation is an anomaly of fetal intestinal development believed to occur in one per 200 to one per 500 live births, with symptomatic malrotation occurring in one per 6,000 live births. Symptomatic malrotation is clinically evident in the first postnatal month in 64% of patients; 82% are diagnosed in the first postnatal year; 18% to 25% of symptomatic patients are diagnosed at 1 year of age and older.1 Between 30% and 62% of pediatric patients with intestinal malrotation also have an associated anomaly, such as duodenal atresia (seen in as many as 17%) and jejunal atresia (33%). Disorders of intestinal rotation are also common in infants and children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and omphalocele.1 However, it is difficult to determine the true incidence of malrotation be- 10 | www.PediatricSuperSite.com 4101CaseChallenges.indd 10 Figure 2. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan obtained through mid-abdomen shows inverted relationship between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) (A) and the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) (B). Source: Dayal B, Blankas-Hernaez N. Reprinted with permission. cause this condition goes undetected during childhood in a significant number of patients. Intestinal Malrotation Intestinal malrotation can be defined as any deviation from the normal 270° counterclockwise rotation of the midgut in utero. During fetal development, the midgut supplied by the superior mesenteric artery grows too rapidly to be accommodated in the peritoneal cavity. Prolapse into the umbilical cord occurs around the sixth week. Between the 10th and 12th weeks, the midgut returns to the abdominal cavity, having undergone a 270° counterclockwise rotation around the superior mesenteric artery. This rotation of intestinal development has been divided into three stages:2 Stage I occurs between 5 and 10 weeks’ gestation; Stage II occurs between 10 and 12 weeks’ gestation; and Stage III lasts from 12 weeks’ gestation until term. Symptoms of Malrotation Many patients with malrotation are often asymptomatic; it can be discovered incidentally during surgery for other conditions.3 However, some may present with chronic symptoms of intermittent bowel obstruction or vague abdominal complaints and even fewer may report acute episodes of agonizing abdominal pain.3 Symptoms may arise from acute or chronic intestinal obstruction that may be caused by the presence of abnormal peritoneal bands (Ladd bands) or a volvulus.4 The classic presentation of malrotation is a newborn infant with bilious vomiting or any child with bilious emesis and abdominal pain. Physical examination may reveal mild distension of the abdomen, diffuse tenderness with or without signs of peritonitis, bloody stool on rectal examination, duodenal obstruction caused by Ladd’s bands, or associated duodenal or jejunal atresia.5 In older children, the clinical presentation of malrota- PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:1 | JANUARY 2012 12/30/2011 12:16:56 PM Case Challenge tion is variable and often insidious. Approximately 30% present with intermittent vomiting (which may be nonbilious) and 20% present with intermittent abdominal pain, as in our case.5 Less common presentations include failure to thrive, solid food intolerance, malabsorption, pancreatitis, peritonitis, biliary obstruction, motility disorders, and chylous ascites.5 Volvulus in Malrotation Volvulus is the most feared complication of intestinal malrotation and is a clear indication for emergent surgery. It occurs when the small bowel twists around the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in vascular compromise to large portions of the midgut. This leads to bowel ischemia and necrosis that becomes irreversible unless corrected quickly.5 More than 50% of children with malrotation present with volvulus before 1 month of age. Among older children with malrotation, 10% to 15% present with volvulus. The onset of symptoms is usually acute, but some children present with a more chronic pattern of episodic vomiting and abdominal pain suggestive of intermittent volvulus.5 Screening and Diagnosis Intestinal malrotation can be screened for and diagnosed with imaging studies, including an upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast series, plain radiographs, contrast barium enema, ultrasonography, or abdominal CT scan. An upper GI contrast series is considered the most reliable because it allows visualization of the duodenum and has an accuracy of more than 80%.5 The upper GI contrast series should be performed under fluoroscopy and by an experienced pediatric radiologist whenever possible. In approximately 75% of cases, the upper GI contrast PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:1 | JANUARY 2012 4101CaseChallenges.indd 11 will see obvious signs indicating malrotation, such as a partial obstruction of the duodenum that may have more of a “beak” appearance if a volvulus is present, or an abnormal positioning of duodenum (ligament of Treitz on right side of the abdomen) that has a “corkscrew” appearance (Figure 3).5,6 Plain radiographs are rarely diagnostic because they are neither sensitive nor specific for malrotation, so they are usually followed by an upper GI contrast series. However, right-sided jejunal markings (Figure 4) or the absence of a stool-filled colon in the right lower quadrant on a plain radiograph may suggest intestinal malrotation.7 A contrast barium enema is useful as an adjunct to the upper GI series and can be used to diagnose volvulus if it shows complete obstruction of the transverse colon. Ultrasonographic findings that suggest of malrotation include a “whirlpool” sign, which corresponds to a clockwise wrapping of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and mesentery around the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and a dilated duodenum, which indicates duodenal obstruction by Ladd’s bands.5,8 Finally, malrotation can be diagnosed on CT by the anatomic location of a right-sided small bowel, a leftsided colon, aplasia of the pancreatic uncinate process, or an inverse relationship of the superior mesenteric vessels (Figure 1, see page 9).9 The superior mesenteric vein is normally located to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, but the relative positions of the vein and artery are reversed in approximately 60% of patients with malrotation.10 However, abnormalities of SMASMV orientation are not entirely diagnostic because some patients with malrotation have a normal relationship, whereas an inverted relationship can Figure 3. Upper GI series clearly demonstrates the “corkscrew” appearance of the proximal small bowel (arrows) as it twists around the superior mesenteric artery in malrotation with a midgut volvulus. Source: Dayal B, Blankas-Hernaez N. Reprinted with permission. Figure 4. Supine frontal abdominal radiograph shows small bowel with jejunal markings (arrowheads) on the right and colon predominately on the left in a patient with malrotation. Source: Dayal B, Blankas-Hernaez N. Reprinted with permission. also be seen in patients without malrotation.9,10 Therefore, an upper GI contrast series remains the gold standard for diagnosing intestinal malrotation. The classic treatment for intestinal malrotation is the Ladd procedure. It involves counterclockwise reduction of the volvulus if present, division of any coloduodenal bands, widening of the mesenteric base to prevent repeated volvulus, and prophylactic appendectomy.11 Generally, symptomatic patients with malrotation require www.PediatricSuperSite.com | 11 12/30/2011 12:16:57 PM Case Challenge surgical intervention. Management of asymptomatic patients discovered incidentally to have malrotation is more controversial, although some surgeons recommend that all patients with malrotation receive laparotomy.12 CONCLUSION On hospital day 2, the patient underwent a Ladd procedure to correct her malrotation, along with an appendectomy. Postoperatively, the patient did well without any complications. She tolerated a regular diet on postoperative day 3 and was discharged on postoperative day 5. The patient made a full recovery; no signs of recurrence were found after 12 months of follow-up. Intestinal malrotation is an important cause of abdominal pain and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal disorders in neonates and older children. Many patients with malrotation are asymptomatic, while others may present with acute or chronic symptoms, such as intermittent intestinal ob- 12 | www.PediatricSuperSite.com 4101CaseChallenges.indd 12 struction, nonbilious vomiting, or recurrent abdominal pain. Intestinal malrotation can be screened and diagnosed using various imaging studies; upper gastrointestinal contrast series is considered the best and most accurate study. The classic treatment for intestinal malrotation is the Ladd procedure, which entails counterclockwise reduction of a volvulus if present; division of any coloduodenal bands; widening of the mesenteric base to prevent repeated volvulus; and prophylactic appendectomy. REFERENCES 1. Hall C, Friedland A, Sundar S, Torok KS, Bhende MS, Pecson G, Leedy C. Index of suspicion. Pediatr Rev. 2008 Jan;29(1):25-30. 2. Anjali P, Hatley R. Intestinal Malrotation. Emedicine from WebMD. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/930313overview. Accessed Dec. 9, 2011. 3. Gamblin TC, Stephens RE, Johnson RK, Rothwell, M. Adult malrotation: a case report and review of the literature. Curr Surg. 2003;60(5):517-520. 4. Gosche JR, Vick L, Boulanger SC, Islam, S. Midgut abnormalities. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86(2):285-299. 5. Brandt ML. Intestinal Malrotation. UpToDate.com. Available at: www.uptodate. com/contents/intestinal-malrotation. Accessed Dec. 20, 2011. 6. Berrocal T, Lamas M, Gutierrez J, et al. Congenital anomalies of the small intestine, colon, and rectum. Radiographics. 1999; 19(5):1219-1236. 7. Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S. Intestinal malrotation in adolescents and adults: spectrum of clinical and imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179(6):1429-1435. 8. Chin L-W, Hsu CK, Wang H-P. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of elderly midgut volvulus in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(7):900-902. 9. Zissin R, Rathaus V, Oschadhy A, et al. Intestinal malrotation as an incidental finding on CT in adults. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24(6);550-555. 10. Applegate KE, Anderson JM, Klatte EC. Intestinal malrotation in children: a problemsolving approach to the upper gastrointestinal series. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1485-1500. 11. Matzke GM, Dozois EJ, Larson DW, Moir CR. Surgical management of intestinal malrotation in adults: comparative results for open and laparoscopic Ladd procedures. Surg Endosc. 2005; 19(10):1416-1419. 12. Maxson RT, Franklin PA, Wagner CW. Malrotation in the older child: surgical management, treatment and outcome. Am Surg. 1995;61(2):135-138. PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:1 | JANUARY 2012 12/30/2011 12:16:59 PM