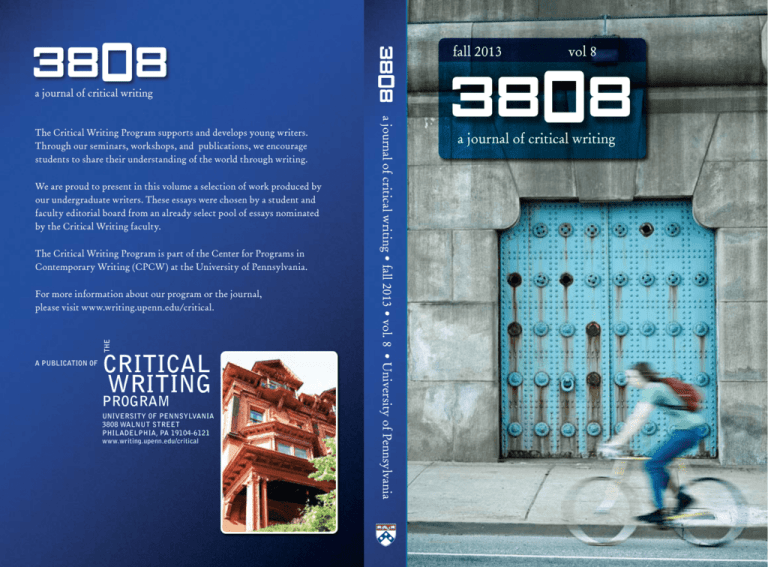

a journal of critical writing fall 2013 vol 8

advertisement