Antibacterial Agents in Dental Hygiene Care

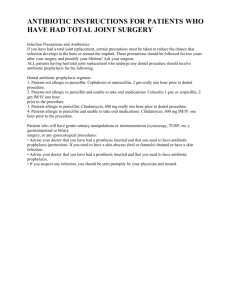

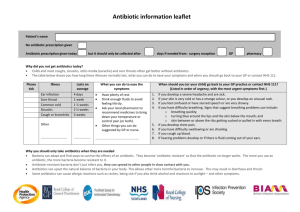

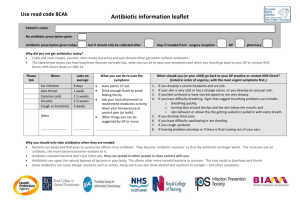

advertisement

Earn 1 CE credit This course was written for dentists, dental hygienists, and assistants. Antibacterial Agents in Dental Hygiene Care A Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by Dr. Howard M. Notgarnie, RDH, EdD Abstract Dental hygiene care incorporates antimicrobial agents as adjunct services with nonsurgical periodontal therapy, and as a measure to reduce the risk of hematogenous infection subsequent to oral tissue manipulation. Knowledge of antimicrobial properties provides practitioners the ability to make sound decisions when diagnosing conditions treated by dental hygiene intervention and choosing antibiotics dentists prescribe for administration. Antimicrobial agents inhibit structural or metabolic functions of microorganisms, but also render adverse effects to patients. Bacterial mutation and acquisition of genetic material enables development of strains resistant to antibiotics. Understanding the interplay of host, microorganism, and antimicrobials fosters advances in therapeutic choices and delivery systems when treating periodontal disease, as well as when responding to the risk of hematogenous infection of endocardium or prosthetic joints. Educational Objectives At the end of this self-instructional education activity the participant will be able to: 1. Explain antibiotic effectiveness as a function of selective toxicity 2. Associate antibacterial agents with their antimicrobial mechanisms 3. Describe how bacteria acquire and exercise antibiotic resistance 4. Describe mechanisms of targeted antimicrobial therapy 5. Choose antimicrobial agents appropriate to periodontal conditions 6. Identify conditions at risk of hematogenous infection 7. Choose agents appropriate for antibiotic prophylaxis 8. Discuss the research pertaining to antimicrobials as adjunctive and prophylactic care Author Profiles Dr. Howard M. Notgarnie has been practicing clinical dental hygiene for 20 years, currently in Colorado. He has eight years experience in professional association leadership and five years teaching experience. He can be contacted at howardrdhedd@gmail.com. Author Disclosure Dr. Howard M. Notgarnie has no commercial ties with the sponsors or providers of the unrestricted educational grant for this course. Go Green, Go Online to take your course Publication date: July 2013 Expiration date: June 2016 Supplement to PennWell Publications PennWell designates this activity for 1 Continuing Educational Credit. Dental Board of California: Provider 4527, course registration number CA#:01-4527-13070 “This course meets the Dental Board of California’s requirements for 1 unit of continuing education.” The PennWell Corporation is designated as an Approved PACE Program Provider by the Academy of General Dentistry. The formal continuing dental education programs of this program provider are accepted by the AGD for Fellowship, Mastership and membership maintenance credit. Approval does not imply acceptance by a state or provincial board of dentistry or AGD endorsement. The current term of approval extends from (11/1/2011) to (10/31/2015) Provider ID# 320452. This educational activity was developed by PennWell’s Dental Group with no commercial support. This course was written for dentists, dental hygienists and assistants, from novice to skilled. Educational Methods: This course is a self-instructional journal and web activity. Provider Disclosure: PennWell does not have a leadership position or a commercial interest in any products or services discussed or shared in this educational activity nor with the commercial supporter. No manufacturer or third party has had any input into the development of course content. Requirements for Successful Completion: To obtain 1 CE credit for this educational activity you must pay the required fee, review the material, complete the course evaluation and obtain a score of at least 70%. CE Planner Disclosure: Heather Hodges, CE Coordinator, does not have a leadership or commercial interest with products or services discussed in this educational activity. Heather can be reached at hhodges@pennwell.com. Educational Disclaimer: Completing a single continuing education course does not provide enough information to result in the participant being an expert in the field related to the course topic. It is a combination of many educational courses and clinical experience that allows the participant to develop skills and expertise. Image Authenticity Statement: The images in this educational activity have not been altered. Scientific Integrity Statement: Information shared in this CE course is developed from clinical research and represents the most current information available from evidence based dentistry. Known Benefits and Limitations of the Data: The information presented in this educational activity is derived from the data and information contained in reference section. The research data is extensive and provides direct benefit to the patient and improvements in oral health. Registration: The cost of this CE course is $20.00 for 1 CE credit. Cancellation/Refund Policy: Any participant who is not 100% satisfied with this course can request a full refund by contacting PennWell in writing. Education Objectives At the end of this self-instructional education activity the participant will be able to: 1. Explain antibiotic effectiveness as a function of selective toxicity 2. Associate antibacterial agents with their antimicrobial mechanisms 3. Describe how bacteria acquire and exercise antibiotic resistance 4. Describe mechanisms of targeted antimicrobial therapy 5. Choose antimicrobial agents appropriate to periodontal conditions 6. Identify conditions at risk of hematogenous infection 7. Choose agents appropriate for antibiotic prophylaxis 8. Discuss the research pertaining to antimicrobials as adjunctive and prophylactic care Abstract Dental hygiene care incorporates antimicrobial agents as adjunct services with nonsurgical periodontal therapy, and as a measure to reduce the risk of hematogenous infection subsequent to oral tissue manipulation. Knowledge of antimicrobial properties provides practitioners the ability to make sound decisions when diagnosing conditions treated by dental hygiene intervention and choosing antibiotics dentists prescribe for administration. Antimicrobial agents inhibit structural or metabolic functions of microorganisms, but also render adverse effects to patients. Bacterial mutation and acquisition of genetic material enables development of strains resistant to antibiotics. Understanding the interplay of host, microorganism, and antimicrobials fosters advances in therapeutic choices and delivery systems when treating periodontal disease, as well as when responding to the risk of hematogenous infection of endocardium or prosthetic joints. Antimicrobial Agents in Dental Hygiene Care Understanding antimicrobial agents is crucial to modern dental hygiene practice. The properties of these agents influence the effectiveness of medications prescribed by dentists or administered to patients. Dental practitioners use a variety of antimicrobials as adjuncts to traditional mechanical dental hygiene procedures. Although the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis has been questioned, dental professionals have a history of attending to patients who might be at risk of hematogenous infections are protected using antibiotics. This article will address properties of antimicrobials with their use in dental hygiene therapy. Properties of Antimicrobial Agents Antimicrobials are chemicals that kill or suppress multiplication of microorganisms. Antibiotics are a subset of antimicrobials that have those antimicrobial effects on bacteria. Clinical practitioners tend to use antibiotic and antimicrobial synony3 | rdhmag.com mously. When using antimicrobials, health-care professionals exploit their effects as anti-infective agents. Antibiotic effectiveness is a result of its selective toxicity: the metabolism of prokaryotic cells makes bacteria susceptible to the toxic effects of antibiotics at far lower concentrations than the concentrations that would adversely affect people, whose cells are eukaryotic. An important factor in antibiotic effectiveness is related to the cell wall structure. Gram-negative bacteria have cell walls with less peptidoglycan than gram-positive bacteria have. Instead, gram-negative bacteria have an extra layer of lipids that protect them from many antibiotics.1 For most infections, the effectiveness of antibiotics does not depend on whether the antibiotic is bactericidal or bacteriostatic. However, endocarditis or meningitis caused by bacterial infection and infections in some immunocompromised patients require bactericidal antibiotics. An antibiotic’s spectrum refers to the number of bacterial species the antibiotic inhibits or kills. There is no clear definition of broad- and narrow-spectrum, but antibiotics clinically effective against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria are generally considered broad-spectrum.1 Antimicrobial Mechanisms Antimicrobial agents have a variety of mechanisms of action. Each mechanism inhibits a key structural or metabolic function. Dental practitioners employ antiseptics such as chlorhexidine (CHX) as antimicrobial agents. CHX exhibits its effects on cell surfaces. The cationic nature of CHX gives it several valuable properties: it sticks to anionic oral surfaces, it attaches to the anionic surfaces of bacteria targeted for treatment, and it does not easily pass through skin and mucous membranes.2 Penicillins and cephalosporins, which contain the β-lactam ring, inhibit synthesis of bacterial cell walls. Human cells do not have these cell walls or the peptidoglycan of which cell walls are composed. These drugs are bactericidal because they bind to enzymes involved in formation of cell walls. With poorly formed cell walls, the bacteria are susceptible to swelling and bursting. As a class, these β-lactam antibiotics are effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria because of the variety of synthetic forms available.1 Quinolones (ciprofloxacin), rifamycins (rifampin), nitroimidazoles (metronidazole), and nitrofurans (nitrofurantoin) are bactericidal because they inhibit nucleic acid production. Inhibition of DNA production prevents reproduction, and inhibition of messenger RNA production prevents cells from making proteins necessary for metabolism. Metronidazole provides a good example of the reason some antibiotic spectra are narrow. Metronidazole inhibits DNA synthesis only in the absence of oxygen; thus only anaerobic bacteria are sensitive to metronidazole.1 An additional antibiotic mechanism is inhibition of ribosomes synthesizing proteins. Tetracyclines inhibit the function of transfer RNA, which carries amino acids to a ribosome building a protein. Aminoglycosides (streptomycin) cause errors in the translation of messenger RNA into protein, thereby causing the resultant RDH | July 2013 protein to malfunction. Macrolides (erythromycin) bind to part of the ribosome, preventing that ribosome from building proteins. These antibiotics’ stronger attraction to bacterial ribosomes than to human ribosomes results in their selective effects on bacteria.1 Sulfonamides provide one more mechanism by which antibiotics are toxic to bacteria. This class of compounds inhibits folate synthesis.1 Folate participates in several enzyme functions in human metabolism, including the formation of nucleotides. Without adequate function of folate and its metabolites, a person is at risk of neurological and vascular disorders.3 Potential for toxic effects on humans is one reason health professionals and patients should use antibiotics cautiously. Antibiotic Resistance Another reason to use caution when considering antibiotics is bacterial resistance. A prime mechanism of antibiotic resistance development is characteristic of natural selection. Most bacteria exposed to an unfamiliar antibiotic will perish, but a few will carry a mutation giving them antibiotic resistance, which future generations will carry. Another method of acquiring antibiotic resistance is incorporating plasmids, small segments of genetic material contributed from a nearby bacterium. The fast reproduction of bacteria leads researchers to fear a time limit to today’s antibiotics and seek new compounds. Bacteria can resist antibiotics by creating an enzyme that destroys or deactivates an antibiotic such as penicillinase, which reduces the effectiveness of penicillins. Bacteria can also develop resistance by a change in the receptor molecule by which an antibiotic gains access to those bacteria. A change in a bacterial cell wall can prevent an antibiotic from reaching that receptor. Finally, bacteria can resist an antibiotic using a protein that pumps out that compound. Given concerns of toxicity, allergy, secondary infections, and resistance, an appropriate antibiotic choice accommodates the patient as well as the particular species of bacteria.1 Furthermore, the practitioner should ensure the antibiotic use is cost-effective. A formulary developed through collaboration among health-care team members, such as that of the Cleveland Clinic, can help health practitioners confidently administer or prescribe antibiotics that efficiently serve patients’ needs.4 Therapeutic Uses of Antibiotics Antibiotics have been an essential component of care for dental infections, characterized by fever and swollen, tender lymph nodes.5 Removal of deposits has been the signature of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. However, a growing body of research provides evidence supporting antimicrobial administration or prescription to patients undergoing nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Targeted or systemic antimicrobial agents can be effective adjuncts to the traditional mechanical treatment. Targeted Therapy There are two mechanisms of targeting antibiotic application. Antibiotics can target bacteria metabolically. Metabolically tarRDH | July 2013 geted antibiotic therapy involves laboratory testing of bacteria for sensitivity to antibiotics, thereby allowing clinicians to prescribe or administer antibiotics that will most effectively kill or inhibit the particular species present in the patient’s infection.1 Testing of oral flora and choosing an antibiotic regimen based on the patient’s plaque composition is a promising method for metabolically targeted antibiotic therapy.6 The other mechanism of targeted antibiotic application is by site specificity. Effective administration requires materials holding the antimicrobial agent to withstand moisture, heat, and motions of the mouth. Furthermore, a substrate that remains in place for an extended time must be less than 1mm thick, soft, and flexible so as not to irritate the patient.7 In a systematic review, CHX used as a mouth rinse reduced plaque and gingivitis scores compared with placebo but caused an increase in staining.2 CHX in a sustained delivery system improved ease of compliance. Reduced risk of adverse effects, and continuous administration balanced the lack of uniformity in dosage associated with the slow release of the drug. This sustained delivery of CHX reduced the load of bacterial plaque and adhesion of the fungus Candida albicans while improving patient experience associated with the taste and staining of CHX mouth rinses.7 A widely studied targeted delivery system for nonsurgical periodontal treatment is the subgingival application of minocycline. In a systematic review, pocket depth and attachment of the periodontium improved more with minocycline or doxycycline than with placebo. This improvement occurred despite no significant difference in plaque index or bleeding on probing. Thus, the authors supported targeted subgingival antibiotic therapy as an adjunct to mechanical removal of deposits.8 Liu and Yang emphasized the direct antimicrobial effects on periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis, Porphyromonas intermedius, Eikenella corrodens, and Fusobacterium nucleatum. An additional benefit of targeted delivery of these tetracycline derivatives is the reduction in the destructive effects of the immune response. These medications modulate several immune responses, including macrophage activity that produces tumor necrosis factor-α. Such modulation improves indications of periodontal health.9 Systemic Therapy Bowen recommended including amoxicillin and metronidazole as a bivalent prescription at the initial phase of nonsurgical periodontal treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP). Patients with GAP exhibit rapid destruction of periodontal tissues despite being generally healthy systemically. Their neutrophils and serum antibodies function abnormally. Differential diagnosis of GAP includes loss of attachment and bone around first molars, mandibular incisors, and at least three other teeth; deposits that do not befit the periodontal destruction; and a family history suggesting susceptibility to GAP. GAP often begins under the age of 30. For GAP patients with pockets up to 6mm, the outcomes of bivalent antibiotic treatment during initial nonsurgical periodontal therapy are better than deciding on systemic antibiotic treatment during rdhmag.com | 4 Table 1. Antibiotic Regimens for Infective Endocarditis Prophylaxis Administration By Mouth Unable to Take by Mouth Age Adult Child Adult Child Standard—Penicillins 2g amoxicillin 50mg/kg amoxicillin 2g ampicillin IV or IM 50mg/kg ampicillin IV or IM 600mg clindamycin 20mg/kg clindamycin 600mg clindamycin IV 20mg/kg clindamycin IV 500mg azithromycin or clarithromycin 15mg/kg azithromycin or clarithromycin 2g cephalexin 50mg/kg cephalexin 1g cephazolin or ceftriaxone IV or IM 50mg/kg cephazolin or ceftriaxone IV or IM Penicillin Allergy— Clindamycin or Macrolides Penicillin Allergy—Cephalosporins* *Not for those with immediate-type penicillin allergic reaction the maintenance phase. Cases beyond that severity usually require surgical intervention to control periodontitis. Limitations of this bivalent antibiotic regimen are clinical significance of improved pockets, adverse reactions to medications, and bacterial resistance. In addition, differentiating GAP from chronic periodontitis is important because systemic antibiotics are not warranted for initial therapy of chronic periodontitis. The recommended protocol is amoxicillin and metronidazole, each 500 mg three times per day for 7 to 10 days.10 Antibiotic Prophylaxis to Avert Sequelae of Bacteremia Frequently, patients have used antibiotics to reduce the risk of hematogenous infection. Bod et al. explained the purpose of antibiotic prophylaxis is to reduce the number of bacteria at the treatment site and to reduce the ability of bacteria to colonize. When using antibiotic prophylaxis, the practitioner should ensure an effective concentration of antibiotic from the beginning of treatment to the end of bacteremia, effectiveness of the antibiotic for the bacteria likely to enter the bloodstream, avoiding multiple doses that might lead to resistant bacterial strains, and the patient’s potential for adverse reactions.11 Nevertheless, researchers widely question the value of antibiotic prophylaxis. For example, case reports have inferred prosthetic joint infection of oral origin, yet no known studies have shown a genetic match. Maintaining good oral health reduces risks associated with bacteremia.12 in patients under 70 and 14.5/100,000 in patients 70 to 80 years of age. Prosthetic heart valves and degenerative heart disease have supplanted rheumatic heart disease as underlying risk factors for IE. New risk factors for IE include use of intravenous drugs and catheters. Moreover, antibiotic prophylaxis does not seem to be cost-effective. Consequently, only people with a high risk for IE undergoing high risk procedures should have antibiotic prophylaxis. These high risk situations include manipulation of gingival tissues on patients with prosthetic heart valves, a history of IE, cyanotic heart disease that has not been repaired or that has been repaired with a prosthesis less than six months ago, or heart disease repaired with a prosthesis near which a defect remains.13 The American Heart Association explained that except in cardiac patients with the highest risk, the relative risks and effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis make routine use of those antibiotics difficult to justify. Infectious endocarditis involves interplay of clotting and immune factors with bacteria in the bloodstream. Bacteria attach to thrombi on cardiac endothelium and reproduce in a vegetation at the attachment site. Turbulence initiates those thrombi.14 Correcting dental problems before prosthetic heart valve replacement, maintaining good oral health, and avoiding procedures that result in bacteremia help avoid IE.13 Windle and Kulkarni (2012) noted antibiotic prophylaxis for IE aims at the most common pathogen for that sequel, Streptococcus viridans. The antibiotic is indicated 30 to 60 minutes prior to beginning care. Table 1 displays antibiotic choices.15 Infective Endocarditis Common signs and symptoms of infective endocarditis (IE) are fever, heart murmur, chills, weakness, and difficult breathing. Treatment of IE depends upon identifying the pathogen and that pathogen’s antimicrobial susceptibility profile. Surgical intervention is often necessary as well. Although Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species are predominant pathogens, other bacterial species, parasites, and autoimmune processes may also cause endocarditis. Changes in recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis reflect a change in epidemiology of IE. Antibiotic overuse has led to bacterial resistance in strains endemic to human environments. Incidence of IE has been very low—less than 10/100,000 Prosthetic Joint Replacement Benoit and Pickett showed the evolution of antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations over the past two decades to demonstrate lack of a clear rationale for antibiotic prophylaxis: • In 1985, a survey reflected that most orthopaedic surgeons did not believe there was a significant relationship between oral procedures and infection of prosthetic joint replacements, yet they recommended antibiotic prophylaxis.12 The most common recommendation was a cephalosporin.16 However, concerns over bacterial resistance to antibiotics led many health professionals to question this practice of antibiotic prophylaxis. 5 | rdhmag.com RDH | July 2013 • In 1997, the American Dental Association (ADA) and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) jointly issued a statement recommending selective antibiotic prophylaxis, which they later updated, in 2003. The guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis addressed time since placement of the prosthesis, systemic health problems, medications, history of complications with the prosthesis, and comorbidities. • In 2009, the AAOS recommended antibiotic prophylaxis of all patients with a total joint replacement for any oral procedures. AAOS did not consult with ADA for this recommendation. • In 2011 the American and Canadian Dental Associations recommended no antibiotic prophylaxis if joint replacement is more than two years old unless the patient has a history of infection in a prosthetic joint or the patient has a compromised immune system. However, AAOS did not rescind its 2009 recommendations.12 Most recently, the AAOS and ADA issued three recommendations based on a systematic review of extant research regarding risk of infection to joint implants. These recommendations are 1) consider discontinuing routine antibiotic prophylaxis; 2) they are “unable to recommend for or against” rinsing with an antimicrobial agent before dental care; and 3) maintenance of oral health is suitable to patients with prosthetic joints. Several peer organizations, including the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, reviewed the recommendations. Studies in the systematic review, informing the first two recommendations, did not show an association between bacteremia and implant infection. In fact, although implant infections are mostly Staphylococcus species, bacteremias associated with dental procedures are mostly Streptococcus species. The third recommendation was a consensus statement based on the benefit of current practices toward good oral health and on evidence that a healthy oral condition reduces bacteremia.17 Similarly, in 2008 British health officials recommended against antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with a risk of IE because there is no evidence of efficacy. There is no evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis reduces infections of prosthetic joints, yet bacteremia after brushing teeth and eating is comparable to that of dental care.12 Berbari et al. showed that dental procedures were not risk factors for prosthetic hip or knee infections.18 Thus the low, 2% prevalence of prosthetic joint space infection is inconsistent with the theory that those infections originate from oral procedures. Furthermore, antibiotic prophylaxis does not prevent bacteremia.12 With the mounting evidence against effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis, Olsen, Snorrason, and Lingaas (2010) advised against antibiotic premedication for dental procedures on patients with joint replacements except in those patients with a high risk for infection. When practitioners prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis for prosthetic joints, Olsen et al. recommended a regimen consistent with that in Table 1.19 RDH | July 2013 Bod et al. recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures when the prosthetic joint is less than two years old, the patient has a compromised immune system, or the patient has a history of prosthetic joint infection. Vancomycin is indicated only when there is a recognizable risk of infection with methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus.11 It is valuable to note that patients with prosthetic joints or a high risk of IE are trying to reduce the risk of an infection subsequent to manipulation of oral tissues. The presumed critical event is bacteremia, which is not associated with the misperception of hierarchy. Thus it would be prudent to question a physician’s rationale when prescribing antibiotic prophylaxis “for fillings but not for cleanings.” Conclusion Dental practitioners and their patients benefit when practitioners understand the pharmacology of antimicrobial agents. Dental hygienists have a history of administering antimicrobials upon the prescription of dentists as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal care. Furthermore, dentists have a history of prescribing antibiotics as a risk-reduction measure for hematogenous infection. Awareness of modern principles gives dental practitioners the opportunity to offer state-of-the-art care to clientele by choosing effective medications and avoiding those with risks outweighing the benefits. References 1. Kaufman G. Antibiotics: Mode of action and mechanisms of resistance. Nursing Standard 2011; 29: 49-55. 2. van Strydonck DAC, Slot DE, Van der Velden U, Van der Weijden F. Effect of a chlorhexidine mouthrinse on plaque, gingival inflammation and staining in gingivitis patients: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2012; 39: 1042–1055. doi:10. 1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01883.x. 3. Fowler B. The folate cycle and disease in humans. Kidney International 2001; 59: S221-S229. 4. Cleveland Clinic. Guidelines for antimicrobial usage. West Islip, NY: Professional Communications. 2012. 5. Goldberg MH, Topazian RG. Odontogenic infections and deep fascial space infections of dental origin. In RG Topazian, MH Goldberg, & JR Hupp (eds.). Oral and Maxillofacial Infections, 4th ed. pp. 158-187. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2002. 6.van Vinkelhoff AJ, Herrera D, Oteo A, Sanz M. Antimicrobial profiles of periodontal pathogens isolated from periodontitis patients in The Netherlands and Spain. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2005; 32: 893-898. 7. Fini A, Bergamante V, Ceschel GC. Mucoadhesive gels designed for the controlled release of chlorhexidine in the oral cavity. Pharmaceutics 2011; 2011: 665-679. 8.Matesanz-Pérez P, García-Gargallo M, Figuero E, Bascones-Martínez A, Sanz M, Herrera D. A systematic review on the effects of local antimicrobials as adjuncts to subgingival debridement, compared with subgingival debridement alone, in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2013; 39: 227-241. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12026. 9. Liu D,Yang PS. Minocycline hydrochloride nanoliposomes inhibit the production of TNF-α in LPS-stimulated macrophages. International Journal of Nanomedicine rdhmag.com | 6 2012; 7: 4769-4775. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34036 10.Bowen DM. Treating aggressive periodontitis. Journal of Dental Hygiene 2011; 85: 244-246. 11.Bod P, Kurtus I, Incze S, Moldovan R, Vâlcu A, Nagy Ö. Clindamycin — An option for antibiotic prophylaxis in arthroplasty. Acta Medica Marisiensis 2011; 57: 574-577. 12.Benoit G, Pickett FA. Antibiotic prophylaxis with prosthetic joint replacement. What is the evidence? Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene 2011; 45: 103-108. 13.Baluta MM, Benea EO, Stanescu CM, Vintila MM. Endocarditis in the 21st century. Maedica: A Journal of Clinical Medicine 2011; 6: 290-297. 14.American Heart Association. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007; 116; 1736-1754. 15.Windle ML, Kulkarni R. Antibiotic prophylaxis regimens for endocarditis 2012; Medscape article 1672902. Retrieved February 5, 2013 on http://emedicine.medscape.com/ article/1672902-overview#a30. 16.Jaspers MT, Little JW. Prophylactic antibiotic coverage in patients with total arthroplasty: current practice. Journal of the American Dental Association 1985; 111: 943-948. 17. American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Dental Association. Prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures: Evidence-based guideline and evidence report. Rosemont, IL: American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2012. 18.Berbari EF, Osmon DR, Carr A, Hanssen AD, Baddour LM, Greene D, Kupp LI, Baughan LW, Harmsen WS, Mandrekar JN, Therneau TM, Steckelberg JM, Virk A, Wilson WR. Dental procedures as risk factors for prosthetic hip or knee infection: A hospital-based prospective case– control study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2010; 50: 8–16. doi: 10.1086/648676. 19.Olsen I, Snorrason F, Lingaas E. Should patients with hip joint prosthesis receive antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment? Journal of Oral Microbiology 2010; 2: 5265-5275. doi: 10.3402/jom.v2i0.5265. Author Profiles Dr. Howard M. Notgarnie has been practicing clinical dental hygiene for 20 years, currently in Colorado. He has eight years experience in professional association leadership and five years teaching experience. He can be contacted at howardrdhedd@gmail.com. Author Disclosure Dr. Howard M. Notgarnie has no commercial ties with the sponsors or providers of the unrestricted educational grant for this course. Notes 7 | rdhmag.com RDH | July 2013 Online Completion Use this page to review the questions and answers. Return to www.ineedce.com and sign in. If you have not previously purchased the program select it from the “Online Courses” listing and complete the online purchase. Once purchased the exam will be added to your Archives page where a Take Exam link will be provided. Click on the “Take Exam” link, complete all the program questions and submit your answers. An immediate grade report will be provided and upon receiving a passing grade your “Verification Form” will be provided immediately for viewing and/or printing. Verification Forms can be viewed and/or printed anytime in the future by returning to the site, sign in and return to your Archives Page. Questions 1.Antibiotic resistance is not related to: a. Bacterial mutations b. Plasmid incorporation c. Rate of bacterial reproduction d. Human drug tolerance 2.Sulfonamides’ antibiotic effects are inhibiting synthesis of: a.DNA b.Protein c.Folate d. Cell walls 3.Implant infections are mostly of what genus? a.Staphylococcus b.Candida c.Porphyromonas d.Streptococcus 4.The defining difference between antimicrobials and antibiotics is: a. Antibiotics are a subset of antimicrobials b. One type affects eukaryotic cells, and the other affects prokaryotic cells c. They affect different types of cell walls d. One type is bacteriostatic, and the other is bactericidal 5.Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental care is intended to avoid: a. Bleeding during dental procedures b. Hematogenous infection of prosthetic joints and endocardium c. Bacteremia associated with brushing teeth and eating d. Poor oral health 9.Antibiotics with a β-lactam ring act by binding to: a.Peptidoglycan b. Anionic surfaces c. Messenger RNA d.Enzymes 10. A substrate for sustained, site-specific antibacterials are more effective if they are: a.Rigid b. Thicker than 1mm c. Kept dry d. Heat tolerant 11. Each of the following directly affects protein synthesis except: a.Rifampin b.Tetracycline c.Streptomycin d.Erythromycin 12. Bacteria may resist antibiotics by all of the following except: a. Preventing the antibiotic from entering the cell b. Destroying the antibiotic c. Pumping out the antibiotic d. Influencing the antibiotic’s toxicity to the host 13. Metabolic antibiotic targeting involves all of the following except: a. Bacterial sensitivity testing b. Plaque composition c. Human sensitivity testing d. Oral flora testing 6.A 7 to 10 day regimen of amoxicillin and metronidazole has been found most effective for which of the following: a. Initial treatment of chronic periodontitis b. Treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis during maintenance phase c. Initial treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis d. Treatment when pockets are ≥7mm in depth 14. Baluta et al. recommended infective endocarditis prophylaxis if the patient has any of the following conditions except: a. Prosthetic heart valve b. History of infective endocarditis c. Prosthetic repair of heart disease with a remaining defect d. Cyanotic heart disease that was successfully repaired >6 months ago 7.Which of these statements about chlorhexidine is true? a. It is an anionic compound b. Its effects are on cell surfaces c. It does not interact with oral surfaces d. It easily passes through mucous membranes 15. Targeted subgingival delivery of minocycline does not affect: a. Bleeding on probing b. Human immune response c. Pocket depth d. Attachment of the periodontium 8.Bacteremia associated with dental procedures is mostly of what genus? a. Staphylococcus b. Candida c. Porphyromonas d. Streptococcus 16. Typical presentation of a person with generalized aggressive periodontitis is: a. Normal immune function b. Under age 30 c. Systemic illnesses are apparent d. Periodontal destruction consistent with deposits RDH | July 2013 17. Changes in antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis involve all the following epidemiological changes except: a. Rheumatic heart disease has become an increasing concern b. Incidence of infective endocarditis is very low c. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not cost-effective d. Antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria are endemic to human populations 18. Windle and Kulkarni named which microorganism the most common pathogen for infective endocarditis? a. Streptococcus mutans b. Staphylococcus aureus c. Streptococcus viridans d. Eikenella corrodens 19. Which of the following inhibits nucleic acid production? a.Penicillin b.Ciprofloxacin c.Sulfonamide d.Tetracycline 20. Bod et al. recommended antibiotic prophylaxis for a prosthetic joint if the patient has any of the following conditions except: a. Prosthetic joint <2 years old b. Pins or screws in a bone c. History of infection in the prosthetic joint d. Compromised immune system 21. Which of the following inhibits nucleic acid production? a.Penicillin b.Ciprofloxacin c.Sulfonamide d.Tetracycline 22. Bod et al. recommended antibiotic prophylaxis for a prosthetic joint if the patient has any of the following conditions except: a. Prosthetic joint <2 years old b. Pins or screws in a bone c. History of infection in the prosthetic joint d. Compromised immune system rdhmag.com | 8 ANSWER SHEET Antibacterial Agents in Dental Hygiene Care Name: Title: Specialty: Address:E-mail: City: State:ZIP:Country: Telephone: Home ( ) Office ( Lic. Renewal Date: ) AGD Member ID: Requirements for successful completion of the course and to obtain dental continuing education credits: 1) Read the entire course. 2) Complete all information above. 3) Complete answer sheets in either pen or pencil. 4) Mark only one answer for each question. 5) A score of 70% on this test will earn you 1 CE credit. 6) Complete the Course Evaluation below. 7) Make check payable to PennWell Corp. For Questions Call 216.398.7822 If not taking online, mail completed answer sheet to Educational Objectives Academy of Dental Therapeutics and Stomatology, 1.Explain antibiotic effectiveness as a function of selective toxicity. 5.Choose antimicrobial agents appropriate to periodontal conditions. 2.Associate antibacterial agents with their antimicrobial mechanisms. 6.Identify conditions at risk of hematogenous infection. A Division of PennWell Corp. 7.Choose antimicrobial agents appropriate for antibiotic prophylaxis. 3.Describe how bacteria acquire and exercise antibiotic resistance. 8.Discuss the research pertaining to antibiotics as adjunctive and prophylactic care. 4.Describe mechanisms of targeting antibiotic therapy. Course Evaluation Objective #2: Yes No Objective #3: Yes NoObjective #4: Yes No Objective #5: Yes No Objective #6: Yes NoObjective #7: Yes No Objective #8: Yes No 2. To what extent were the course objectives accomplished overall? 5 4 3 2 1 0 3. Please rate your personal mastery of the course objectives. 5 4 3 2 1 0 4. How would you rate the objectives and educational methods? 5 4 3 2 1 0 5. How do you rate the author’s grasp of the topic? 5 4 3 2 1 0 6. Please rate the instructor’s effectiveness. 5 4 3 2 1 0 7. Was the overall administration of the course effective? 5 4 3 2 1 0 8. Please rate the usefulness and clinical applicability of this course. 5 4 3 2 1 0 9. Please rate the usefulness of the supplemental webliography. 4 3 2 1 0 Yes No 11. Would you participate in a similar program on a different topic? Yes No If paying by credit card, please complete the following: MC Visa AmEx Discover Acct. Number: ______________________________ Please evaluate this course by responding to the following statements, using a scale of Excellent = 5 to Poor = 0. 10. Do you feel that the references were adequate? For IMMEDIATE results, go to www.ineedce.com to take tests online. Answer sheets can be faxed with credit card payment to (440) 845-3447, (216) 398-7922, or (216) 255-6619. P ayment of $20.00 is enclosed. (Checks and credit cards are accepted.) 1. Were the individual course objectives met? O bjective #1: Yes No 5 P.O. Box 116, Chesterland, OH 44026 or fax to: (440) 845-3447 Exp. Date: _____________________ Charges on your statement will show up as PennWell 12. If any of the continuing education questions were unclear or ambiguous, please list them. ___________________________________________________________________ 13. Was there any subject matter you found confusing? Please describe. ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ 14. How long did it take you to complete this course? ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ 15. What additional continuing dental education topics would you like to see? ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ AGD Code 016 PLEASE PHOTOCOPY ANSWER SHEET FOR ADDITIONAL PARTICIPANTS. COURSE EVALUATION and PARTICIPANT FEEDBACK We encourage participant feedback pertaining to all courses. Please be sure to complete the survey included with the course. Please e-mail all questions to: hhodges@pennwell.com. INSTRUCTIONS All questions should have only one answer. Grading of this examination is done manually. Participants will receive confirmation of passing by receipt of a verification form. Verification of Participation forms will be mailed within two weeks after taking an examination. COURSE CREDITS/COST All participants scoring at least 70% on the examination will receive a verification form verifying 1 CE credit. The formal continuing education program of this sponsor is accepted by the AGD for Fellowship/Mastership credit. Please contact PennWell for current term of acceptance. Participants are urged to contact their state dental boards for continuing education requirements. PennWell is a California Provider. The California Provider number is 4527. The cost for courses ranges from $20.00 to $110.00. PROVIDER INFORMATION PennWell is an ADA CERP Recognized Provider. ADA CERP is a service of the American Dental Association to assist dental professionals in identifying quality providers of continuing dental education. ADA CERP does not approve or endorse individual courses or instructors, nor does it imply acceptance of credit hours by boards of dentistry. Concerns or complaints about a CE Provider may be directed to the provider or to ADA CERP at www.ada. org/cotocerp/. The PennWell Corporation is designated as an Approved PACE Program Provider by the Academy of General Dentistry. The formal continuing dental education programs of this program provider are accepted by the AGD for Fellowship, Mastership and membership maintenance credit. Approval does not imply acceptance by a state or provincial board of dentistry or AGD endorsement. The current term of approval extends from (11/1/2011) to (10/31/2015) Provider ID# 320452. Customer Service 216.398.7822 RECORD KEEPING PennWell maintains records of your successful completion of any exam for a minimum of six years. Please contact our offices for a copy of your continuing education credits report. This report, which will list all credits earned to date, will be generated and mailed to you within five business days of receipt. Completing a single continuing education course does not provide enough information to give the participant the feeling that s/he is an expert in the field related to the course topic. It is a combination of many educational courses and clinical experience that allows the participant to develop skills and expertise. CANCELLATION/REFUND POLICY Any participant who is not 100% satisfied with this course can request a full refund by contacting PennWell in writing. © 2013 by the Academy of Dental Therapeutics and Stomatology, a division of PennWell ANTIAG713RDH