True West - Joshua Ruebl

advertisement

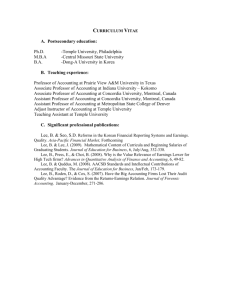

1 “True West” and the Metaphysical Desert Sam Shepard is one of America’s most renowned and prolific playwrights. He is known for his energized, stark productions illustrating social breakdown and the American psyche. Various plays such as Fool for Love, Buried Child, The Unseen Hand, and True West, reveal a society of somnambulists looking for a connection to an everfleeting sense of community and to the earth. His characters are at odds both with each other and a harsh landscape in what read as epic battles with the sensation of individuals coming painfully into selfhood. In these plays, gesture and language take on a heightened realism, referring to twentieth century Absurdism, Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, the Romanticism of Whitman and Emerson, and rock n’ roll and the avantgarde of the 1960’s and 1970’s. His most recent works are new takes on the family drama, but they still retain mystical elements of his early works. Shepard’s 1980 family drama True West, best illustrates the theories of metaphysics and identity of his oeuvre and these are interwoven through the dramatic action and illustrated through the transformation of the two major characters Lee and Austin. To understand Shepard’s work, one must trace his influences back to the avantgarde of the early twentieth century and the theatre theories of Antonin Artaud. The Theatre of Cruelty, Artaud’s vision of a new theatre as described in his tract The Theatre and its Double, sought to “make language express what it does not ordinarily express: to make use of it in a new, unaccustomed fashion; to reveal its possibilities for producing a physical shock; to divide and distribute it actively in space; to deal with intonations in an absolutely concrete manner, restoring their power to shatter as well as really to manifest something; to turn against language and its basely utilitarian, one could say alimentary, sources, against its trapped-beast origins; and finally, to consider language as the form of Incantation.”i Much of nineteenth century Western theatre prior to the advent of Surrealism and Artaud’s theories used a style of naturalistic writing as evidenced by the work of Henryk Ibsen and elements of Naturalism. Much of this theatre espoused utilitarian liberal humanist principles and the style of the dialogue was like Renaissance painting’s 2 “window into real-life.” Artaud wished to move beyond these didacticisms and return language to the rhythms and poetics of early Western theatre and return a tragic and poetic element back to the productions. Instead of providing the meaning, thesis, and action of the play for improving society, Artaud sought a different utility for the language of the theatre. He wanted to use it as a ritual incantation that would affect the space around the stage itself in a musical expression of human pain. In addition to this percussive, poetic, and violent usage of language, Artaud advocates a heightened gesture of sensation in acting that gives an experience of suffering and of human beings pushed beyond their limits. Ultimately, the theatrical experience envisioned by Artaud would “furnish the spectator with the truthful precipitates of dreams, in which his taste for crime, his erotic obsessions, his savagery, his chimeras, his utopian sense of life and matter, even his cannibalism, pour out, on a level not counterfeit and illusory, but interior.”ii This internal struggle is evident in much of Shepard’s work, but it is most evident in the brothers of True West. Throughout this analysis, True West, will be broken down from beginning to end, and major points referencing Artaud’s theories will be examined, relating them to Shepard’s work of this period. Though steeped in the tradition of realism and the American family drama, Shepard’s middle-period work is an evolution from the American absurdism of Edward Albee and the European type of Samuel Beckett (whom he was influenced by in his early work.) Usage of Artaud’s heightened dramatic techniques in regards to acting and language will also be analyzed within the context of this heightened neo-realism. The play begins with Austin, a young, college-educated screenwriter and family man who sits working on selling a screenplay for a large sum to a Hollywood studio. He’s looking after his mother’s suburban Los Angeles home while she is on vacation. The dwelling used to be surrounded by desert, but the landscape is now transformed into a sprawling suburb. Austin, writing by candlelight, sits in the kitchen at a typewriter in a typical middle-class dining room decorated with all the obvious accoutrements. The directions for the set and action call for sounds that enhance the tension. These include loud cricket chirps and occasional sounds of Southern California coyotes baying in the distance- all of which are at a heightened intensity. This creates a mood of displacement 3 and anxiety with the mise en scene, revealing a tension between the urban environment and the wildness which is always buried underneath or at the periphery, referring to atavistic tendencies simmering beneath the set’s fabricated suburban setting. Austin’s college educated, complacent urban “family man” persona is counterbalanced in the beginning by his brother Lee- a drifter from the desert who has just arrived back into his old life to reconnect with his family and engage in an intense sibling rivalry. As Austin sits at the typewriter, Lee prowls in the background, representing at once the past and also the wilderness buried underneath the sprawling concrete community around them. Lee makes reference to their mother’s habitual cleanliness and Lee’s writing by candlelight. This candlelight Lee references to “the Forefathers,” who wrote by “candlelight in the wilderness.”iii This seems to be a reference to a mythological West of frontiersmen, battle, and manifest destiny. The cabin in the wilderness is now a suburban tract home surrounded by an entire prefabricated almost kitschy environment. Lee is the atavistic representative of the “Forefathers”- the archetype of the rugged male individualist that tries to tame the natural landscape. The play with its heightened gesture and use of shadow and extreme punctuations of violence in language immediately start a musical undercurrent to the dramatic action, much like Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty with its contortions of pain. The Naturalistic façade of the play is undone by door slams, hard footfalls, baying coyotes, and language delivered in a tight, pared-down, violent cadence. It becomes clear that the conflict with Lee is at once a family squabble but at the same time intensely internal. It is as though Lee is an exteriorized self, a double of Austin in a contemporary dreamscape of the American West. The “double” is a concept in Western mysticism referring to mankind’s shadow self- a doppelganger representing our internal dark side, the untamed soul that cannot exist in our socialized world. At the moment of death, it is said that a human being sees their shadow self in the mirror. Artaud believed that theatre was mankind’s “double” and that the actor on stage was the transmitter of a powerful stage presence of “force/form dualism” to brutalize forms.iv This dualism in the Theatre of Cruelty “is to lift the veil of appearances which conceals the violence of creation itself, a violence begun in disastrous conjunctions but perpetuated as the disguised cruelty of the world of fixed forms.”v 4 Humanity’s dual nature is the crux of many esoteric theories of both the East and the West. In Kabbalism, the goal of the Great Work in following the sepharic pathways is to have a balance between one’s light and dark dualities. At the point of balance is the concept of gnosis or self-understanding. Sam Shepard refers in an interview with Don Shewey in a conversation about spiritualist G.I. Gurdjieff, that Shepard “always felt envious of people who feel themselves to be whole. I’ve never felt that ever in my life. I feel like I’m many. I don’t mean schizophrenic or neurotic. We are split.”vi Sam Shepard’s work deals specifically with the split consciousness in humanity and like Artaud’s “double,” his characters fight against their dual nature and the illusory solid world around them. According to Jeanne de Salzman, a Gurdjieff acolyte, one must “try for a moment to accept the idea that you are not what you believe yourself to be, that you overestimate yourself. That you always lie to yourself every moment, all day, all your life…You will see that you are two…One who lies and one who cannot endure lies…Learn until you have seen the difference between your two natures, until you have seen the lies, the deception in yourself. When you have seen your two natures, that day, in yourself, the truth will be born.”vii In his essay “Born Injured: The Theatre of Sam Shepard” Christopher Bigsby writes that Shepard has a “fascination with the self as still center and site of deep division” which references Gurdjieff’s and Artaud’s views on consciousness and that “myths and rituals (are) expressive of an underlying sense of unity behind the surface alienations and fractures of contemporary life.”viii This is a perfect metaphor for Austin’s illusory Hollywood world in a collision with the other, more feral and unpredictable world of nature represented by Lee’s intrusions. In Scene Two of True West, Austin is shown watering plants in his mother’s house while Lee questions him on his intellectualism and his ability to integrate himself into an upper-middle class world of socialites. Lee is impressed with his brother’s ability to be socially mobile rather than taking part in his own world of crime and theft. Lee finds Austin’s suburban world hollow, empty, and unreal. Both brothers long for their childhood, where they lived in a house surrounded by nature and an open desert. Lee had been spending time in the Mojave before he returned to his old life and he remarks that 5 the old natural lifestyle had changed. The anxiety of the removal from nature is revealed in this passage of dialogue: LEE. I went up in the foothills there. Up in the San Gabriels. Heat was drivin’ me crazy. AUSTIN. Well, wasn’t it hot out in the desert? LEE. Different kind of heat. Out there it’s clean. Cools off at night. There’s a nice little breeze. AUSTIN. Where were you, the Mojave? LEE. Yeah. The Mojave. That’s right. AUSTIN. I haven’t been out there in years. LEE. Out past Needles there. AUSTIN. Oh yeah. LEE. Up here it’s different. This country’s real different. AUSTIN. Well, it’s been built up. LEE. Built up? Wiped out is more like it. I don’t even hardly recognize it.ix At this point in the play, tension is building. Lee is unstable from living years in the desert. Austin is sheltered in his family life, suburbia, and his delusional Hollywood aspirations. Austin has been made soft and complacent by the routines of modern life. His connection with nature is lost, hence his comment about the area being “built up” as reference to the taming of nature as progress. Lee has spent considerable time living on intuition and criminal behavior. As the play progresses, the antagonism between the worldviews of the two brothers explodes into physical violence. Lee is Austin’s double and vice-versa. Both are having a life-transforming collision with each other. Both bring out in each other mirroring aspects of the other’s personality. When Saul, a script agent for Hollywood, comes to meet Austin to discuss contracts, Lee pitches a “real Western” idea to him. After a discussion with Lee, Saul agrees to the contract. This sparks a fierce competition between Austin and Lee. Austin believes that he has a right to the contract because he’s the one that’s been assiduously writing a “sellable” Western. Lee however, convinces Saul of the authenticity of his 6 experience and Lee recruits Austin to be the “filter” to the typewriter for his experiences relating to the desert. Throughout the play, Lee serves in a surreptitious way to break down the socialized world that Austin inhabits- a world that is illusory and pre-fabricated. Austin has worked very hard to keep his life ordered, safe, and somnambulistic. Lee taunts him, questions his existence, and insinuates that Austin has made a living for himself by buying off their father with Hollywood “blood money.” The hidden truth is that Lee and Austin’s father disappeared into the desert and lives as an alcoholic. Lee accuses Austin of trying to paint him in the same light as their father. It is well known that Sam Shepard’s father was a World War II veteran and an alcoholic who lived as a hermit in the desert of New Mexico, drinking himself into a stupor. It seems as though Lee and Austin are the two halves of the author’s interior self now caught in an eternal battle. It is in the characterization of Austin and Lee that Shepard delves most specifically into his mystical interpretation of human consciousness and how we relate to the land. What Shepard rejects is the notion of psychology in relation to understanding the character’s motives. Instead he wishes to take us on a transcendent journey into the vastness of our interior landscape, an arid one full of daytime heat, anxiety, and nighttime frigidity. When we move through Shepard’s play, it is as though the desert is an apt metaphor for the vastness and emptiness of the American psyche, an emptiness that cannot be adequately described by any contemporary theories of psychology or economics. “Psychology,” says Artaud, “which works relentlessly to reduce the unknown to the known, to the quotidian and the ordinary, is the cause of the theatre’s abasement and its fearful loss of energy, which seems to me to have reached its lowest point. And I think both the theatre and we ourselves have had enough of psychology.”x As the play progresses and Lee and Austin work together, intoxicated, writing the screenplay for their filmic “True West,” it is as though the two characters merge into one. They are both drunk, angry, lost in a state of nature. Though the anger and the tension are there, it seems as though a camaraderie is beginning to develop, and that the two halves are being united into a cohesive and creative whole. Lee staggers drunk, dictating dialogue, while Austin, sitting drunk at the typewriter on the floor, “shapes” his brother’s uneducated tendencies into something workable. A breakdown in Austin has just 7 occurred. Austin has gone and broken into the neighbors’ homes, stealing toasters to prove himself as “authentic” as his brother, to get inside that creative space he thinks his brother inhabits from having such an encounter with the desert. Everything in the house is destroyed: phone cords are ripped out of the walls, plants dumped on the floor, and the toasters have been burned and smashed with golf clubs. Lee dictates lines for his character in the play. This character is on “intimate terms” with the desert, with its darkness and light. At a moment of inspiration, Austin and Lee’s mother returns from her Alaskan trip. She is the symbol of both the mother goddess and the archetypal American housewife- one which is almost a 1950’s stereotype. Her mind is scattered, her gestures unsure, dreamlike, and sleepy as she stumbles into Lee and Austin’s (and possibly Shepard’s) interior creative universe. She notices the devastation of her numerous plants and remarks, “that’s one last thing to take care of,” referring to her natural urges denied by her artificial surroundings. Shepard’s work is difficult to categorize, for he straddles the line between Modernism and Post-Modernism. He refers to Hollywood, America’s mythology surrounding the Westward expansion, and includes Post-Modern elements when he uses a pastiche of the American family drama to create an intense Theatre of Cruelty based on American archetypes. However many Post-Modern elements he contains, he never falls prey to the irony or identity politics associated with much of Post-Modern theatre. Rather he seems linked to the Romantics and to the best elements of Modernism. This according to Sheila Rabillard, is Shepard’s “search for grounding and presence in the artistic medium and offering above all a theatrical experience disturbing to modernist myths of origin, originality, and the unified authorial self.”xi When Austin and Lee’s mother remarks that Picasso is visiting Los Angeles at the county art museum, Austin immediately remarks that Picasso is dead. This may be at first read, a line that illustrates their mother’s shaky state of mind. However if one looks at the thesis of the play and its reference to the split in consciousness of the individual, of society, and ultimately the artist himself, one realizes that Picasso and his Modernist unified “genius authorship” has been shattered by the Post-Modernist world of division and fragmentation. 8 Austin tells his mother that he and Lee will be moving out to the desert to live together. He feels as though he needs to reconnect with the nature that has disappeared around him. At this time, he is drunk and nearly feral. Lee contradicts him and tells his mother that Austin will be staying behind and that he will be venturing out alone. This enrages Austin, who takes a ripped-out phone cord and jumps on Lee’s back, wrapping it around his neck. Their mother stands in shock as her two “boys” struggle on the floor. Here is where the final transformation occurs. Austin is now Lee and vice-versa. Austin finally lets Lee go and it seems as though Lee is dead. Then Lee bursts up after a long pause and their struggle continues as the stage lights lower to an orange sunset with the silhouettes of the brothers struggling eternally in the desert. In describing his work, Shepard “feel(s) that language is a veil holding demons and angels which the characters are always out of touch with. Their quest in the play is the same as ours in life- to find these forces, to meet them face to face and end the mystery.”xii It seems as though Shepard, through the brothers in True West, has gone into his own interior world and meet the demons and angels face to face. In our Post-Modern world, which denies the universal truth or the meta-narrative, Shepard’s personal authorial presence in the age of the death of the author is an anomaly. True West retreats into the universal truth of dualism and it’s spiritual reconciliation. What Shepard has done is returned theatre to its tradition of aesthetics and away from Post-Modernism’s need for art to become “social utility.” Though there are elements of pastiche and a subtle irony beneath Shepard’s work, he does not allow PostModernism’s ironic objectivity to move us away from the metaphysics and the beauty of violent physical energy simmering beneath the surface of the play. Austin and Lee’s struggle before death and into eternity is a direct reference to our split psyche. These archetypes are seen again and again throughout the history of Western art. At the turn of the twentieth century, Naturalism, industrialization, and a changing society tended to view art as social therapy, political in nature (i.e. for the dispensation of “political truths”) and invested in trends in psychology. Artaud saw this current as stultifying and representing a decline in the theatre and sought to return the theatre to animistic visions. In his manifesto The Theatre and it’s Double, he writes 9 “Either we will be capable of returning by present-day means to this superior idea of poetry and poetry-through-theatre which underlies the Myths told by the great ancient tragedians, capable once more of entertaining a religious idea of the theatre (without meditation, useless contemplation and vague dreams), capable of attaining awareness and a possession of certain dominant forces, of certain notions that control all others, and (since ideas, when they are effective, carry their energy with them) capable of recovering within ourselves those energies which ultimately create order and increase the value of life, or else we might as well abandon ourselves now, without protest, and recognize that we are no longer good for anything but disorder, famine, blood, war, and epidemics.”xiii Shepard increasingly has spoken disparagingly of political theatre, calling it “extremely boring”xiv and instead looks for a sculptural, aesthetic theatre of interior emotional and experience. In describing True West he has referred to Artaud’s concepts of the body and mind along with Western metaphysics, saying that he has “wanted to write a play about double nature,” and that “we’re split in a much more devastating way than psychology can ever reveal.”xv He also has attributed influence to the anthropological writings of Carlos Castaneda, who had spent years doing fieldwork studying alternate consciousness and mystical systems with Yaqui Indian tribes in the Southwestern desert of the U.S. and in Mexico. Castaneda in his research with a shaman named Don Juan Matus, wrote of our consensus reality as but a description made by those giving names to things from birth onwards, that humans are split and that reality is a shared hallucination. Castaneda believed that the secrets of consciousness lie in the desert. In a January 1978 letter to Joseph Chaikin, Shepard refers to Castaneda’s work on shamanic lucid dreaming, saying that it had been an “inspiration for me along the lines I’ve been working on, which has to do with a feeling of separation between my body and ‘me.’ This feeling is only periodic and comes in small flashes, but seems to act on me like a sudden insight into another world.”xvi Shepard takes these influences from both Eastern and Western mysticism and indigenous spirituality to make sense of our nation’s consciousness. Though not always exclusively spiritual, his plays offer a dark, unnatural ambience and an inexplicable violence, as though these brutal urges are inescapable in the American male psyche. No overt explanation for these eruptions occur in the text, but when Lee and Austin are pitted against each other, it seems as though it is a natural part of the American experience. As 10 an audience member, these scenarios seem all too familiar. Shepard has spoken of the transient nature of American society, as though the ground itself offers no solid foundation to the split American soul. The violence of this separation seems unbearable to many in our culture. Shepard takes us on a journey through the underside of the American Dream, the fleeting sense of community and the divided self. His characters are not illustrations of psychological theory, but rather archetypes. In True West, Shepard shows us the tenuous divide between normalcy and madness, the rational and the irrational. He uses twentieth century theories of the metaphysical theatre, including those of Artaud’s “double,” along with his own experience to illustrate the decline caused by rigid adherence to social roles, the destruction of nature, and the alienation created by sprawling suburban communities. Through his exaggerations and theatrical devices of sound, movement, and poetic language, he takes us into another world, a double of our own, where we can watch our primordial human pain erupt volcanically on the stage. 11 NOTES i Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and its Double, (New York: Grove, 1958) 46. ii Artaud, 92. iii Sam Shepard Seven Plays, (New York: Bantam, 1986) 6. iv Jane Goodall, Artaud and the Gnostic Drama, (New York: Oxford, 1994) 105. v Goodall, 106. vi Don Shewey “Rock and Roll Jesus with a Cowboy Mouth,” American Theatre Magazine, April, 2004: 2. vii Shewey, 1. viii Christopher Bigsby, “Born Injured: The Theatre of Sam Shepard,” The Cambridge Companion to Sam Shepard, ed. Matthew Roudane (UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002) 12. ix Shepard, 11. x Artaud, 77. xi Sheila Rabillard, “Shepard’s Challenge to the Modernist Myths of Origin and Originality: Angel City and True West” Rereading Shepard, ed. Leonard Wilcox (New York: St. Martins, 1993) 78. xii Rabillard, 87. xiii Artaud, 80. xiv Shewey, 3. xv Rabillard, 103. xvi Joseph Chaikin and Sam Shepard, Letters and Texts, 1972-1984, ed. Barry Daniels (New York: Penguin, 1989) 40. 12 Bibliography Artaud, Antonin. The Theatre and It’s Double. New York, NY: Grove Press, 1958. Blumenthal, Eileen. Joseph Chaikin: Directors in Perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1984. Brook, Peter. The Empty Space. New York, NY: Avon Books, 1968. Castaneda, Carlos. Journey to Ixtlan: The Lessons of Don Juan. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster Press, 1972. Chaikin, Joseph. Joseph Chaikin & Sam Shepard: Letters and Texts, 1972-1984. New York, NY: New American Library Books, 1989. Chaikin, Joseph. The Presence of the Actor. New York, NY: Atheneum Press, 1972. Goodall, Jane. Antonin Artaud and the Gnostic Drama. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1994. Hart, Lynda. Sam Shepard’s Metaphorical Stages. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press Inc. 1987. 13 King, Kimball. Sam Shepard: A Casebook. New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc. 1988. Roudane, Matthew. The Cambridge Companion To Sam Shepard. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Shepard, Sam. Seven Plays. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1986. Shewey, Don. Rock N’ Roll Jesus With a Cowboy Mouth Revisited: An Interview With Sam Shepard. New York, NY: New American Theatre Magazine, 2004. Wade, Leslie A. Sam Shepard and the American Theatre. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 1997. Wilcox, Leonard. Rereading Shepard. Contemporary Critical Essays on the Plays of Sam Shepard. New York, NY. St. Martin’s Press, Inc. 1993.