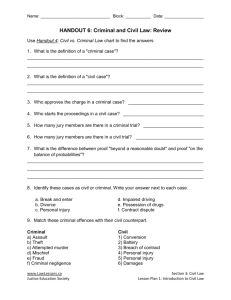

comparative criminal law - University of Toronto Faculty of Law

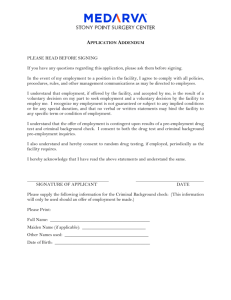

advertisement