Law Student Training Manual - Utah Crime Victims Legal Clinic

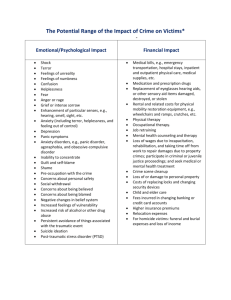

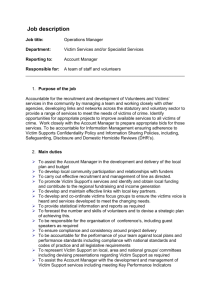

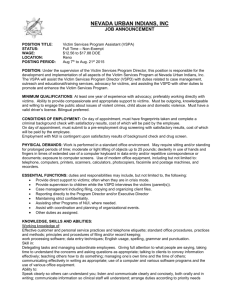

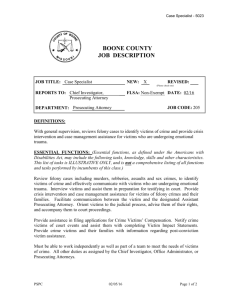

advertisement