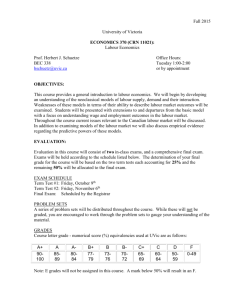

Principles of Economics - Online Library of Liberty

advertisement