Egeland-Marianne-Gravdahl-Master

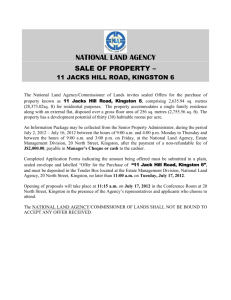

advertisement