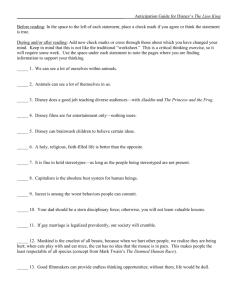

through the looking glass

advertisement