The McMahon-Hussein correspondence

advertisement

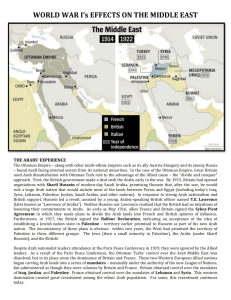

The McMahon-Hussein correspondence Factsheet Series No. 140, Created: October 2011, Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East What is the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence? solely upon whether you will reject or admit the proposed frontiers.”6 With the entry of the Ottoman Empire on Germany’s side in Nov., 1914, many English officers stationed in the Middle East believed that an Arab revolt against the Ottomans would be key to bringing down Britain’s Ottoman enemy. 1 As a result, Sir Henry McMahon, Britain’s High Commissioner to Egypt, opened discussions with Sharif Hussein of Mecca – an influential Arab leader at the time. Throughout these discussions, McMahon promised an independent Arab state – between Iran and Egypt – to Hussein in return for an Arab revolt against the Ottomans.2 The most important of the letters, which had the effect of bringing the Arabs into the war on the British side, was that written by McMahon on October 24th, 1915. In it, with the key passage quoted below, McMahon pledges the British to “recognise and uphold the independence of the Arabs” in areas prescribed by Sharif Hussein: Thus began what is known as the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, between Jul. 1915, and Jan. 1916, wherein the British bargained with Sharif Hussein over the terms under which the Arabs would revolt against the Turkish Ottoman Empire.3 It is in this correspondence, the Arabs assert, that the British conceded a future independent Arab state should include the territory of Palestine. The Arabs ultimately revolted against the Turks in 1916, and fought in a series of campaigns which ended with the capture of Damascus in Sept., 1918. The British denial of any intent or promise to create an Arab state in Palestine is the source of much Arab bitterness. Why is there discrepancy between the British and Arab interpretations over the correspondence? “The districts of Mersin and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo [modern day Lebanon], cannot be said to be purely Arab, and must on that account be excepted from the proposed delimitation. “Subject to that modification, and without prejudice to the treaties concluded between us and certain Arab Chiefs, we accept that delimitation. “As for the regions lying within the proposed frontiers, in which Great Britain is free to act without detriment to the interests of her ally France, I am authorised to give you the following pledges on behalf of the Government of Great Britain, and to reply as follows to your note: “THAT, SUBJECT TO THE MODIFICATIONS STATED ABOVE, GREAT BRITAIN IS PREPARED TO RECOGNISE AND UPHOLD THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE ARABS IN ALL THE REGIONS LYING WITHIN THE FRONTIERS PROPOSED BY THE SHARIF OF MECCA.”7 The correspondence, which began in July of 1915, was conducted in evasive language on both sides, with effusive floweriness in the observance of official titles and honorifics. The core of the correspondence, though, concerns Arab demands for independence, and British reluctance to commit to those demands. Specifically, the British were reluctant to delineate the area of such Arab independence.4 All of the correspondence was in Arabic, with the British translating their original English text with varying degrees of accuracy. 5 Sharif Hussein’s own letters were written in a style that did not permit easy translation, however he clearly tells McMahon that the issue of their negotiations “depends Sharif Hussein of Mecca Sir Henry McMahon Was Palestine within the area of Arab independence? The name “Palestine” is not mentioned in the correspondence between Sharif Hussein and McMahon. Following the War, British Mandate Palestine subsumed the Turkish Ottoman administrative regions of Sanjaq of Jerusalem and part of the Vilayet of Beirut (see the map opposite). In modern-day terms, this region includes all of Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. Finally, Antonius points out that – in arguments that Britain made to France in other documents – Britain mentions that Israel/Palestine could not be allocated to the French. In justification, Britain argues that this region had been reserved for an independent Arab state, as follows: The British said this territory was not included within the area of Arab independence because McMahon’s letter excluded “portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo.” The word “district”, claimed the British, was equivalent to “vilayet.” The British argued that “since the ‘Vilayet of Damascus’ included that part of Syria [now Jordan] which lay to the east of the River Jordan, it followed that that part of Syria [Palestine] which lay to the west of the Jordan was one of the portions of territory reserved [i.e. excluded] in McMahon’s phrase.”8 That is, the British claimed that, since the Turkish district which included Damascus was a long north-south district, the British exclusion included all territory west of that Turkish district – territory which includes modern-day Israel/Palestine. George Antonius demonstrates that this argument is untenable: “In the first place, the word districts …. could not have been intended as the equivalent of vilayets, because there was no such thing as the ‘Vilayet of Damascus’, the ’Vilayet of Homs’ and the ‘Vilayet of Hama’. There was one single Vilayet of Syria of which Damascus was the capital, and two smaller administrative divisions of which Homs and Hama were the principle towns. Sir Henry McMahon’s phrase can only make sense if we take his districts as meaning ‘districts’ in the current sense of the word, that is to say, the regions adjacent to the four cities, and his reservation as applying to that part of Syria – roughly from Sidon to Alexandretta – which lies to the west of the continuous line formed by those four cities and the districts immediately adjoining them.”9 Further, Antonius argues that “[McMahon] refers to the regions which he wished to exclude as being ‘in the two Vilayets of Aleppo and Bairut’. Had he had in mind Palestine, he would certainly have added ‘and the Sanjaq of Jerusalem’. The fact that he did not goes to confirm the conclusion that the only portions of Syria which it was proposed at the time to reserve in favour of France were the coastal regions of northern Syria [i.e. modern-day Lebanon].” “[Palestine] – must [therefore] in default of any specific agreement to the contrary, necessarily remain within the area of Arab independence proposed by the Sharif and accepted by Great Britain. 10 1 Lawrence, T.E. “Seven Pillars of Wisdom”, Introduction to Chapters 1-7. Egypt was at that time a de facto British protectorate, under nominal Ottoman overlordship. The High Commissioner was effectively the ruler. 3 The correspondence is replicated in Antonius, George, “The Arab Awakening”, 1938, Appendix A. 4 Tom Segev opines that the British were either deliberately vague in their wording to mislead the Arabs, or that is was just carelessness. “One Palestine, Complete”, p46. 5 Antonius, p166-67. 6 Ibid. p168. 7 Ibid. p170. 8 Ibid. p78 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid. p. 179. 2