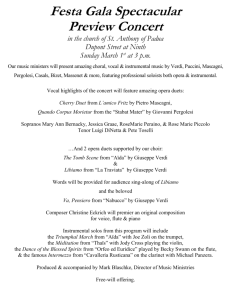

La Traviata Program Notes

advertisement

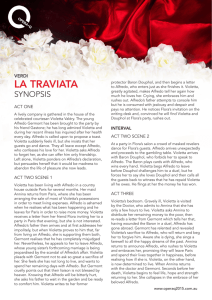

SYNOPSIS Act I Violetta’s house in Paris Violetta Valéry is having one of her many parties. Among her guests are her friend Flora, the Marchese d’Obigny, and Baron Douphol. Gastone arrives with his friend Alfredo Germont whom he introduces to Violetta as one of her ardent admirers. Violetta is flattered by Alfredo’s devoted attention. When she serves champagne, he sings the well-known ”Brindisi Libiamo ne’lieti calici.” When the guests begin to leave for the ballroom, Violetta starts to go with them but has a sudden fainting spell. She bids the others go without her, and all except Alfredo leave. He expresses his concern for her health and warns that she must abandon her frivolous way of life. He tells Violetta of his love for her (“Un dì felice”). She responds that she can only offer friendship. Gaston asks them to join the others, but Alfredo prepares to leave. Violetta gives him a camellia she is wearing and tells him he may return to her when it wilts. He promises to come the following day and again tells her of his love and happiness. Alone, Violetta sings of her joy and of the love Alfredo has kindled in her heart (“È strano!...Ah, fors’ è lui”). Suddenly she thinks of her way of life and decides to forget Alfredo and continue to live life day by day for pleasure (“Sempre libera”). Act II Violetta’s country home near Paris Alfredo has convinced Violetta to leave her life in the city and they are living together in the country. He sings of his happiness (“Dei miei bollenti spiriti”). Annina, Violetta’s servant, tells him she has been in Paris to sell Violetta’s possessions in order to pay their expenses. A shocked Alfredo leaves for Paris to recover Violetta’s things and to clear her debts. Soon she enters, looking for Alfredo, and is surprised to learn he has gone to Paris. When Giuseppe brings her a letter bearing an invitation from Flora, Violetta reads it and tosses it aside. A guest is announced; he is Giorgio Germont, Alfredo’s father. While he is impressed when he learns that they have been living on her money rather than Alfredo’s, he asks her to sacrifice her love. Alfredo’s sister is betrothed, and her fiancé will leave if her brother continues with his scandalous lifestyle (“Pura siccome un angelo”). Violetta tells of her love and happiness, but Germont, although sympathetic with her plight, assures her Alfredo’s love will not last. She finally agrees to leave her lover, but asks Germont to tell both his daughter and Alfredo of her sacrifice after she is dead (“Dite alla giovine”). With an embrace, Germont tells her he is grateful and departs. Quickly Violetta writes a note accepting Flora’s invitation and a letter to Alfredo. When he returns, she says she must leave but tearfully asks him to love her as she will always love him (“Amami, Alfredo”). After she goes, a messenger appears and hands Alfredo her letter. As he reads, his father returns. The letter is Violetta’s farewell, and Germont attempts to console his shocked and disconsolate son (“Di Provenza il mar”). Alfredo then sees the letter from Flora and rushes off in a fit of jealousy. Act III Flora’s home The guests are entertained by gypsies who are telling fortunes. After dancers perform an imitation bullfight, Alfredo enters alone. Soon Violetta arrives with Baron Douphol. Alfredo gambles with him and wins. When supper is announced, the Baron promises to continue the game later. All leave, but Violetta and Alfredo return. She warns him to leave; she fears the Baron will kill him. He promises to leave if she will follow him, but she tells him she has made a solemn vow to see him no more. When he demands to know to whom she made the vow, she lies, telling him it was the Baron with whom she is now in love. Angrily he calls the guests back and, announcing that Violetta has spent everything she had on him, throws his purse of winnings at her feet. He has now paid her back in full! She faints, and the shocked and angered guests demand he leave. His father, who has just arrived, also denounces him. When Violetta revives, she tells the remorseful Alfredo she still loves him. As the curtain falls, the Baron challenges him to a duel. Act IV Violetta’s bedroom, some time later A poignant prelude portrays the mortally ill Violetta. Her doctor tells Annina that she will probably die by nightfall. Violetta rereads a letter she has received from Giorgio Germont in which he tells her that the duel has been fought and the Baron wounded. He has told his son of her sacrifice, and Alfredo is on his way to beg her forgiveness. Violetta knows it is too late (“Addio al passato”). As the sound of revelers is heard from outside, Alfredo rushes in, begs her forgiveness and asks her to leave with him forever (“Parigi, o cara, noi lasceremo”), but she weakens and falls into a chair. Annina goes for the doctor, and soon returns with him and the elder Germont who admits he has wronged Violetta and blesses her. Violetta gives Alfredo a miniature portrait of herself, telling him he must give it to the girl he will one day marry (“Se una pudica vergine”). Feeling a sudden surge of energy, she speaks of being reborn, then falls lifeless as Alfredo calls her name. Synopsis by Dr. Nicolas Reveles, San Diego Opera PROGRAM NOTES Since Dumas’ novel and play were so well known, Verdi was able to omit some of the facets of the story that would have offended the censors; the audiences could fill in the gaps. (The play had been performed in Venice just a week before the première of the opera.) Venice was one of the few cities in which such a story could be told without extensive changes. Still there were a few problems. Verdi wanted it to reflect the contemporary scene but the censors insisted it be moved back to about 1700, the time of Louis XIV, so the “lascivious” goings-on would not be seen as a reflection of “modern” life. The original title, Amore e morte (Love and Death) also had to be changed. (Traviata is the past participle of the verb traviare meaning to go astray so “la traviata” is the “one who has gone astray.”) Verdi had provisionally agreed to the casting of Violetta with the option of changing his mind by a certain date. In his preoccupation the date passed. Though he tried to make a change, his request was denied. Against his wishes, Violetta was sung by Fanny Salvini-Donatelli who was not young and was somewhat large for a dying consumptive. He thought the singers did not understand their roles and criticized them to their faces at the final rehearsal, not a tactic to instill confidence in them. Piave quotes him as saying: “The whole company is unworthy of the great Teatro La Fenice…I have no hopes for the outcome which will be a total fiasco, and so the interest of the management will be sacrificed,…and so will my reputation be sacrificed.” Thus predisposed for failure, Verdi reported that it was a total fiasco. This has been repeated over and over, giving the impression that the première was a disaster. In fact, it was a considerable success. The public began to shout for Verdi after the prelude and called out again and again during the performance. Reviews said that the music was magnificently played and “the public was ravished by the most beautiful and lively melodies that have been heard in a long time.” They did criticize the voices of the singers and the consensus was that he should try again with a better cast. However, there was also dissension, for example: “The love depicted by Verdi is voluptuous, sensual, totally lacking that angelic purity found in Bellini’s music…Verdi was unable to resist the temptation of setting to music a filthy and immoral subject with the aim of rendering it more common and acceptable.” In particular, the fair sex had to be protected from such spectacles, “which insinuate poison into the soul.” La Traviata was repeated nine times during its first season, and the attendance and reception continued to improve, being better than many other productions at La Fenice that season. Genoa and Naples wanted to produce the work immediately but Verdi refused. After a few changes, and with a better cast, it appeared again in Venice in 1854 and was a resounding success! Now he could say: “Then it was a fiasco, now it is creating an uproar!” Today it is one of the most popular operas in the repertory, many equally healthy sopranos have sung the role of Violetta, and the time is usually set about 1850 in accordance with Verdi’s original wishes. La Dame aux camélias [Francesco Maria Piave’s libretto for La Traviata is based upon the novel La Dame aux camélias by Alexandre Dumas, fils. The following article traces the creation of that work. - NMR] Alexandre Dumas, fils (son), born in Paris in 1824, is considered one of the foremost French dramatists of the nineteenth century. He was the illegitimate son of Alexandre Dumas, pére (father), the author of such novels as The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. Dumas was raised by his seamstress mother, Catherine Labay, until his father legally recognized him and assumed responsibility for his care. He attended college but left before receiving a degree. His illegitimacy caused him much unhappiness, both in private school and in college where he had few friends. At age seventeen, he moved in with his father, soon adopted his extravagant lifestyle and fell into debt. At the theatre one evening he first saw Marie Duplessis, already famous in the demimonde for her beauty and ability to get men to spend money on her. In an episode reflected in the opera, he was at her home one day when a coughing episode resulted in her spitting up blood. He urged her to change her way of life, but she replied, “I should die. This life of excitement is what keeps me alive.” He offered the kind of life she would need to get well, and she finally agreed upon the condition. “You are not to spy on me, you are not to ask questions; I shall live exactly as I please without giving you any account of what I do.” Thus began liaison, as a result of which Dumas was soon deeply in debt. Finally, he decided he must break with her and sent her the following letter. 11 La Traviata Verdi and La Traviata Since Alphonsine Plessis, better known as Marie Duplessis, died a few months before Verdi’s first trip to Paris in 1847, he would not have met her. However, it is entirely possible that Giuseppina Strepponi knew her; she certainly would have known of her. In 1852, the couple was in Paris and saw Dumas’ La Dame aux camélias. Verdi had promised a new work for La Fenice in Venice and Piave was working on a libretto for a subject not now known. The composer told him to stop immediately and to begin a new work to be based on Dumas’ play. This is a testimony to the effect the piece had had on him because earlier he had said: “I don’t like prostitutes on stage.” He composed what was to become La Traviata, completing most of it in four weeks while he was still rehearsing Il Trovatore. PROGRAM NOTES My dear Marie, I am neither rich enough to love you as I should like, nor poor enough to be loved by you as you would like. There is nothing for us to do but forget — you a name which must mean very little to you; I a happiness which is no longer possible for me. Needless to tell you how miserable I am, since you know how I love you. So, this is goodbye. You are too tenderhearted not to understand the reason for this letter, too intelligent not to forgive me. A thousand souvenirs, — A.D. He was on a trip to Spain and North Africa when he learned that she was gravely ill. He wrote to her, telling her he would return and ask for her forgiveness. But he waited too long. Duplessis died of tuberculosis in 1846. Her tragic death, along with bitterness over his illegitimacy, inspire Dumas to write the novel La Dame aux camélias (The Lady of the Camellias), portions of which are based on the Duplessis-Dumas affair. The name of the hero, Armand Duval, is a thin disguise for the author. Actually, Dumas tells the story in the third person as it was related to him by Armand Duval. The Music of La Traviata It is difficult for us to imagine today how revolutionary La Traviata must have seemed to contemporary audiences. Today it is a standard repertory item, and most of us are familiar with its tunes and more famous dramatic moments. But considering the traditions of Italian opera as exemplified in the operas of the bel canto period which preceded the appearance of Verdi’s masterpiece, La Traviata could not be more different. Perhaps the greatest difference is the tinta or color of the piece: whereas most Italian operas of the period were given to grandiosity, Verdi’s 1853 opera has an almost chamberlike texture favoring intimacy over bombast. Listen to the prelude, for instance, which is meant to be played by the strings of the orchestra as softly as possible. This is a terribly difficult moment to bring off because it is so exposed and so obviously calculated to produce a special effect. But it perfectly introduces a story about flawed, fragile human beings and sets the audience up for a tragedy that will unfold in the enclosed Parisian settings of salon, country house and bedroom. Of course, the opera has a large enough number of ‘hit’ tunes to rival even Bizet’s Carmen. Verdi knew how to use a tune, especially to carry the action of the drama. The carefree, swaggering nature of the drinking song in Act I perfectly characterizes the nature of the party at hand. Through the use of sheer melody, the duet “Un dì felice” establishes the two very different characters of Alfredo and Violetta: Alfredo ardent and lyrical, Violetta (at least at this point in the drama) flighty and restless. And the glorious “Amami, Alfredo,” used as the basis for the orchestral prelude, returns in Violetta’s vocal line as she leaves the country house in Act II, a particularly telling instance of Verdi’s use of thematic reminiscence. Verdi’s sensitivity to text (and sub-text!) is apparent throughout the drama. The perfect example is the elder Germont’s duet with Violetta, an extraordinary sevenmovement piece that charts the heroine’s psychological arc from indignant rage to selfless acceptance of her fate. Simultaneously, the duet follows Germont’s movement from stern, protective father to consoler and friend. Knowing how demanding Verdi was on his librettists, it is not far-fetched to believe that these humanly true depictions of the characters’ emotional journeys were dictated by the composer himself in order to have something substantial to develop musically. The music supports the characters’ development in every way, making this one of the most perfect scenas in all opera. Add to these attributes the use of dance music as accompaniment to conversation in Act I, the concertato at the end of Act III, (initiated by Alfredo’s tossing of the money in Violetta’sface, a shocking coup de theatre for the time), the reminiscence of love duet music during the final scene and the false recuperation of the heroine just before her death, and you have an opera whose music and text are perfectly intertwined, a model for all composers to follow. There is simply no end to the glories of La Traviata, and its popularity is well deserved. Program Notes by Dr. Nicolas Reveles, San Diego Opera La Traviata - Der Eklat am Spieltisch. Oil painting attributed to Carl d’Unker (1828-1866).