diaspora-development nexus: the role of ict

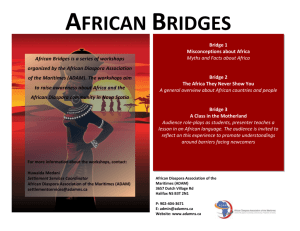

advertisement