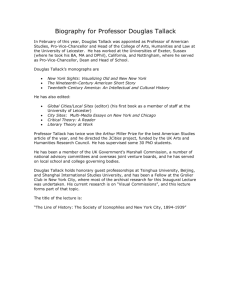

Article PDF - Florida State University College of Law

advertisement