Primary Surgery, Chapter 81

advertisement

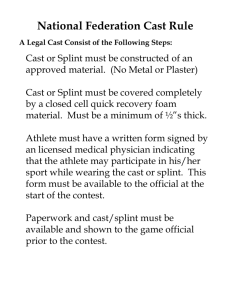

CHAPTER 81 The tibial shaft 81.1 Introduction 81.2 The principles of treatment The tibia is the most common major long bone to be injured. It has a long subcutaneous surface, so fractures of the tibia are the commonest open fractures. If you don’t treat these fractures carefully, they cause much disability. As you see from the long list of ’difficulties’ we give later (81.13), they really can be difficult. Internal fixation is possible, but is never advisable under the conditions for which we write (69.1). External fixation is also possible, but the standard equipment for it is expensive ($ 2000 for a single tibia), and you need special training to use it. Simpler methods of external fixation are being devised, and when these have been adequately evaluated, they may be described in later editions of this manual. The only method of external fixation we do describe is the incorporation of two Steinmann pins in a cast (81.12). Fortunately, you can use the closed methods described in this chapter for all the fractures of a patient’s lower leg. They avoid an operation, and the simpler ones require only a few days admission to hospital. They do not always succeed, but your failures will be less awful than those of internal fixation. You will at least avoid the distress of seeing a metal plate firmly fixed in a dead ununited bone at the bottom of a wound pouring pus. The fragments of a patient’s broken tibia are much more likely to unite satisfactorily, if. (1) You get the fragments into an acceptable position to begin with. And (2) you let him walk on his fracture inside a snug well fitting cast early, and con- EXAMINING THE LOWER LEG The patient’s anterior superior iliac spine, the middle of his patella, and his big toe are usually in a straight line. Compare them with his uninjured leg. If he has had a leg injury, and they are not in line, suspect a fracture. Feel the subcutaneous border of his tibia, and ’spring’ his fibula on it, by squeezing them together. If either of them is fractured, this will be painful. Have you examined his dorsalis pedis and his posterior tibial pulses? Test his peroneal nerve for power (Can he extend his toes?) and sensation (Can he feel a pin prick on the dorsum of his foot?). Record your findings before doing anything else. X-RAYS Take an AP and a lateral view. Raising an injured lower leg in a distal limb injury: (1) Eases the patient’s pain. (2) Reduces the swelling. (3) Minimizes the stiffness that follows the organization of any oedema fluid. (4) Enables you to apply a cast to a limb from which most of the swelling has gone. This will make it less likely to become loose subsequently. So splint and elevate all leg fractures before you manipulate them, operate on them, or put them in a cast. Elevate a patient’s injured leg during an operation, and in the ward afterwards. Elevate it from the moment you see him in casualty, until swelling is no longer a problem. Resting his leg on a chair or on pillows is not enough. His injured leg must be higher than his heart. So, raise the end of his bed on a stool or chair, or on 30 cm blocks for several days if necessary. Encourage him to move his foot and ankle actively, so as to improve the circulation in his calf muscles. Explain how important this is to all your ward staff. RAISE ALL SEVERELY INJURED LEGS ELEVATE AN INJURED LEG watch the circulation in his toes No! This is not good enough fractured tibia cast split pillows Fig. 81.1: RAISING AN INJURED LEG: (1) Eases the patient’s pain. (2) Reduces the swelling. (3) Minimizes the stiffness that follows the organization of oedema fluid. (4) Enables you to apply a cast to a limb from which most of the swelling has gone. Kindly contributed by Peter Bewes. 1 81 The tibial shaft tinuously. Start as soon as the swelling has subsided, during the first few days after the injury, and sometimes as early as the first day. Early weight bearing will not make infection worse, but it may shorten his leg 1 or 2 centimetres, particularly in oblique fractures, where one fragment can easily slip over another. Although this is not ideal, it is not important, because he can, if necessary, compensate for up to 4 cm of shortening by tilting his pelvis, or, if he wears shoes, by having one of them raised. You can, however, usually prevent excessive shortening by a short period of traction to start with. A little shortening (78.1) is a small price to pay for the much greater certainty of union. But there is no way in which he can compensate for the non–union which all too often complicates attempts to prevent shortening. Shortening is even less important in children, because a child’s fractured tibia will grow faster than his normal one on the other side, and will compensate for some, if not all, of it. Although traction for 6 weeks or more is very useful for treating fractures of the femur, never apply it for more than 2 weeks for an uninfected fracture of the tibia, because traction for longer than this encourages non–union. Sometimes, if a tibial fracture is open and infected, you may need to apply traction for as long as 3 weeks while you treat the patient’s soft tissue injury. Apply traction from a Steinmann pin through his calcaneus (70.12), or his distal tibia (80.5). If his fracture is open or badly comminuted, his leg swollen, and his circulation poor, a week or two in traction will help to align the fragments while his soft tissues heal. Some surgeons apply traction to all but the easiest transverse tibial fractures. Others use it only for severely comminuted open ones. As with the femur (78.4), try not to distract the fragments. Uncomplicated fractures of an adult’s tibia take 16 weeks to heal. Children’s fractures heal faster. Healing is delayed if the tibia is comminuted, if soft tissue injury is severe, or if a fracture is open or infected, union may take a year or more. Dehne E. and Nitz et al. The treatment of Fractures by Direct Weight bearing. enough to bear his weight. (4) He may have to walk several kilometres in the rain, so if it is likely to get wet, paint it with oil paint. (5) Fit his cast with a stirrup or, less satisfactorily, with a walking heel, which will raise it out of the mud and puddles. A stirrup will last longer because it is stronger and will distribute his weight more evenly. You will get the stirrup back when you change his cast, so a stock of stirrups is a useful investment. If you fit a walking heel, the patient should be able to pivot on it. This means that: (a) it must be sufficiently narrow, which is why trying to mould a sandal to the sole of a cast is less satisfactory, (b) it must project about 2 cm below the sole of the cast to allow his foot to rock, and (c) it must be aligned with the anterior surface of his tibia. There is no point in removing any leg cast, unless it is loose, until the patient is walking on it painlessly without a stick. If he is walking with pain or difficulty, the cast usually needs to be replaced with another one in which treatment can continue. DON’T REMOVE A CAST UNTIL THE PATIENT IS WALKING PAINLESSLY WITHOUT A STICK 81.4 A long leg walking cast This is the first cast for an unstable fracture of the tibia. Its purpose is to immobilize the fragments and to get a patient walking as soon as he can. (1) Make sure that a patient’s foot points in the right direction to begin with, because a foot which points in the wrong direction is a great disability, especially if it points inwards. So, in all tibial and malleolar casts (82.6), make sure that his foot points in the same direction in relation to his knee on the injured side as it does on the normal one. Journal of Trauma 1961;1:514–535 MAKE SURE HIS FOOT POINTS IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION GET THE FRAGMENTS INTO AN ACCEPTABLE POSITION GET THE PATIENT WALKING EARLY INSIDE A CAST A B C 81.3 Casts for the lower leg A patient can walk and bear weight in any of the following three casts. In order of decreasing stability, but increasing mobility and , convenience, they are: (1) a long leg walking cast from his groin to the bases of his toes, (2) a short leg walking cast from just below his knee to the bases of his toes, and (3) a plaster gaiter from just below his knee to just above his ankle. A long leg cast is applied first, and renewed if necessary, followed by shorter ones as his fracture heals. If a patient walks on the sole of his cast it soon becomes useless, and children, especially, rapidly wear through the soles of their casts. So the way in which a cast is made is important: (1) The patient’s ankle should usually be in neutral. (2) His heel and his foot must also be in neutral and not be everted or inverted. (3) The sole of the cast should be strong 2 lower fragment this angle varies from one patient to another Fig. 81.2: MAKE SURE THE PATIENT’S FOOT POINTS IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION. Some patients have feet which are almost parallel, like patient A. Others, like patient C, have markedly externally rotated feet. Symmetry is more important than making sure that a patient’s feet always point in the same direction as his patella. Patient A’s cast was applied with the lower fragment in too much external rotation. This is undesirable, but too much internal rotation would have been worse—see Fig. 78-3. Kindly contributed by John Stewart. 81.4 A long leg walking cast neck of his fibula. CAUTION! (1) If you neglect to pad the neck of the patient’s fibula, the cast may compress his common peroneal nerve and cause foot drop. (2) Don’t apply the cast with his leg horizontal, because controlling the position of the fragments will be more difficult. (3) If you fail to align the fragments, union will take longer and his leg will be crooked. Make the cast in two parts. A LONG LEG WALKING CAST A B C align the fragments pad his leg let his leg hang down First part. Use two 15 cm plaster bandages to make a thin below–knee cast which is just strong enough to control the fragments. This is easily done if the patient’s knee is flexed over the end of the table so that gravity helps to align the fragments. apply the distal part of the cast D distal part of the cast now firm I E these are the parts of a walking heel F support cast complete the upper part of the cast G H rubber this is the result of not fitting a walking heel No! heel protrudes far enough to allow foot to rock walking heel aligned with anterior surface of tibia Fig. 81.3: MAKING A LONG LEG WALKING CAST. A, the patient’s leg must hang down so that you can align the fragments more easily. B, applying the padding. C, applying the distal part of the cast. D, the distal part of the cast is now firm and the upper part is being completed. E, and F, a locally made walking heel. G, how a walking heel should be aligned with the tibia. H, what happens if you don’t fit a walking heel. I, if possible, fit a stirrup like this. Kindly contributed by John Stewart. (2) The cast must stop the distal fragment rotating on the proximal one, and so delaying union. When union is well advanced, rotation is less likely, but the fragments can easily rotate in a recent fracture. Prevent the proximal fragment from rotating by applying a long leg cast with the patient’s knee in 15◦ of flexion. Prevent the distal fragment from rotating by including his foot and ankle in the cast. MAKE SURE THE PATIENT’S FEET ARE SYMMETRICAL PREVENT THE FRAGMENTS FROM ROTATING ON ONE ANOTHER A LONG LEG WALKING CAST Let the patient’s leg hang over the end of the table. If he is conscious, let him sit on the table. If he is anaesthetized, pull him down to the end of the table, and let his legs hang over it. Pad his injured leg paying especial attention to his malleoli, the subcutaneous surface of his tibia, and the head and Second part. When the below-knee part of the cast has hardened, ask one assistant to hold the patient’s lower leg, and another one to support his thigh. Cover the first part of the cast with a further layer of plaster from his toes to his groin, with his knee in 15◦ of flexion. If you apply it in full extension, it will be less effective in controlling rotation, and his knee will be painful. Apply enough layers of plaster bandage for the upper part of the cast to grip the lower part. Incorporate medial and lateral slabs to strengthen the knee part of the cast. Finally, apply some more turns of bandage to make the upper part adequately strong. CAUTION! (1) While you are applying the cast, check the position of the patient’s ankle carefully; it should be in neutral, and neither inverted nor everted. (2) Make sure that his foot has the same relation to his patella as on the uninjured side. (3) A normal tibia has a slight natural inward bow, so try to restore this. (4) Make a shelf of plaster under his toes, to protect them and prevent flexion contractures. (5) Take care to strengthen the knee, and the ankle parts of the cast, because these are its weakest places. If the patient’s fracture is very recent, split the cast from top to bottom that evening (70.4). Monitor the circulation in his feet meanwhile. Make sure you split the cast on the same day that you apply it, but don’t split it immediately, because the junction of the top to bottom parts of the cast take an hour or two to become sufficiently firm to split. If he has been in calcaneal traction for 2 weeks, any swelling will have gone, so there is less need to split the cast. Don’t worry about a little angulation in a recent fracture. If necessary, correct this 2 or 3 weeks later, when the healing bone at the fracture site is still soft, and more stable. Either wedge the cast (70.7) or, preferably, replace it by another one with his leg in a better position. Replacing a cast is safer and less likely to cause pressure sores than wedging. CAUTION! (1) If possible, admit him, so that he does not walk on his cast until it is dry and hard. This may take 24 hours or more in wet weather. If he walks on a soft cast, it will soon become useless. (2) Be sure to tighten or renew the cast if his leg becomes loose within it. If you fail to do this, the fragments may displace. CLOSING A CAST If you split it and the swelling has gone down, close it with a few turns of plaster bandage. If it is loose, remove a small strip of plaster from the front of it, and then close it with with a few turns of plaster bandage. This is easily done with an electric cast cutter. FIT A STIRRUP OR A WALKING HEEL Either fit them immediately, or later, when the patient’s wound is no longer 3 81 The tibial shaft a problem and he can manage crutches. If possible, fit a metal stirrup. If you don’t have one, fit a walking heel. There are several ways of making a heel. Even a piece of wood is better than nothing: (1) Nail a piece of car tyre to a wooden block, mould this to the cast with a plaster bandage, and bind it on with more bandages, as in Fig. 81-3. (2) Cut a piece from the tyre of a small car, put this around the cast, and hold it in place with laces. ALTERNATIVELY: (1) Start the cast by applying medial and lateral slabs, or a posterior slab only. This will make a smoother cast. (2) Incorporate strips of bamboo in the cast, particularly across fracture lines and joints. This is a considerable economy in plaster. TRIANGULAR COMPRESSION A the leg below the knee is triangular in cross section, this enables you to anchor a below knee cast B oblique upper end pressure with your fingers GOOD C BAD D DIFFICULTIES WITH LONG LEG CASTS If the patient’s ANKLE SWELLS when the cast is removed, treat it by raising his leg, asking him to do exercises, and compressing the swelling with a crepe bandage. Swelling is so common as to be normal, and soon improves. If his KNEE IS STIFF when you remove the cast, one reason may be that you left it on too long. DONT’T LET A PATIENT WALK HOME IN A WET CAST thickness where it is needed unnecessarely thick Fig. 81.5: TRIANGULAR COMPRESSION. While a short leg cast is setting, compress its upper end so as to mould it to the patient’s leg.After Sarmiento. 81.5 A short leg walking cast You can use a shorter cast to protect a fracture of the middle or lower third of a patient’s tibia as soon as the fracture has become stable and the swelling has gone. A shorter cast is not absolutely necessary, and some surgeons don’t use them. The advantages of a short cast are that: (1) It allows a patient to move his knee earlier; if you fit him with A SHORT LEG WALKING CAST a gaiter, as described in the next section, he can also use his ankle earlier. (2)’A short cast uses less plaster than a long one. As with a long leg cast, try to prevent the fragments from rotating. There are two ways you can do this: (1) You can mould the cast carefully to the patient’s upper leg, using Sarmiento’s total contact method of triangular compression, as described below. Or, (2) you can pass a Steinmann pin through the upper end of the patient’s tibia and incorporate it in the cast. This is the most certain method, and is the one to use if he has a fracture of his femur in the same leg (78.6). Sarmiento A, A functional below knee cast for tibial fractures. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery. 1967; 49A: 855 Sarmiento A, Below the knee total contact cast. cast moulded around patellar tendon cast allows knee to flex Fig. 81.4: A SARMIENTO TYPE SHORT LEG WALKING CAST is applied with the patient’s knee flexed to 90°. It has an oblique upper edge, and is moulded by triangular compression, as in the next figure. 4 Clinical Orthopaedics. 1972;82:213 A SARMIENTO SHORT LEG WALKING CAST Apply a cast from just proximal to the patient’s toes, to as high as possible in his popliteal fossa with his leg bent to 90◦ . Bring the cast above his tibial tuberosity in front, and below his popliteal fossa behind, so that it has an oblique upper end as in Fig. 81-4. As the cast hardens, apply compression between the patient’s upper calf and the anterior surface of his leg, as in Fig. 81-5. This will give the cast a triangular cross–section, as in A in this figure, and help to prevent rotation. CAUTION! (1) Triangular compression is safe in a short leg cast, where muscular activity can relieve excessive pressure. But, don’t apply it in a long leg cast, because pressure necrosis can occur. (2) Don’t try to economize by cutting off a long leg cast below the knee. It is always loose and unstable. 81.8 Fatigue fractures of the tibia FRACTURES OF A SINGLE BONE MAKING A PLASTER GAITER CHILDREN adhesive strapping padding strapping turned up strapping incorporated in cast Fig. 81.6: MAKING A PLASTER GAITER. Use this for protecting fractures of the middle third of the tibia as it heals. Kindly contributed by Peter Bewes. 81.6 A plaster gaiter This is the simplest and lightest leg cast; it is the easiest one to walk with, but it is also the least secure. Use it for protecting fractures of the middle third of the tibia, after union has taken place. It does not provide enough stability for fractures of the proximal or distal thirds. If you put it on immediately after a patient has been in a long leg cast, his foot and ankle will swell immediately. Some surgeons don’t use gaiters. MAKING A PLASTER GAITER Apply pieces of adhesive strapping to either side of the patient’s leg, as if you were going to apply traction. Pad his leg and especially his Achilles tendon. Then apply the cast. Just as you apply the last layer of plaster bandage, fold up the two pieces of strapping and incorporate them in the cast. They will stop it slipping down his leg and rubbing against the top of his foot. As the cast sets, mould it around the expanding upper and lower ends of his tibia, so that it grips them firmly. His knee, foot, and ankle should be free. 81.7 Closed fractures of the shaft of the tibia (alone) in adults Two kinds of injury can break an adult’s tibia without breaking his fibula: (1) If his leg is struck from the side, it may break transversely or obliquely, leaving his fibula intact, and thus able to splint the fragments, so that they shift very little. (2) A combination of compression and twisting can cause a long spiral oblique fracture with almost no displacement, and very little soft tissue injury. These fractures usually heal rapidly. CLOSED FRACTURES OF THE SHAFT OF THE TIBIA IN ADULTS REDUCTION If displacement is minimal, leave the fragments as they are. If displacement is significant, anaesthetize the patient and reduce them. Apply a long leg cast or medial and lateral splints, held with a crepe bandage until the acute swelling has subsided. Close the cast, fit a walking heel, get the patient up as soon as he can bear weight with crutches, and make him bear weight on his leg. long spiral oblique short oblique transverse transverse spiral solitary fracture of tibia Fig. 81.7: FRACTURES OF THE SHAFT OF A SINGLE BONE IN THE LOWER LEG. A, a long spiral oblique fracture heals readily. B, a short oblique fracture takes longest to heal. C, a transverse fracture. D, and E, transverse and spiral fractures of children. F, a fracture of the fibula only. If he has a long, spiral oblique fracture, discard the long leg walking cast in about 6 weeks, and apply a protective gaiter for another 2 weeks. If he has a transverse fracture, it will probably take 12 to 16 weeks to heal. It will heal sooner if the fragments are nicely impacted and he starts weight bearing immediately. If the fracture is in the middle third of his tibia and has united, fit a plaster gaiter (81.6). If the fracture is elsewhere, fit a short leg walking cast. Continue protection until he has no pain when you spring his tibia and fibula together. As soon as his tibia is solid and no longer springy, remove the cast or gaiter. If he has a short oblique fracture, expect it to heal more slowly due to the shearing stress. Remove his long leg cast at 8 weeks, and test for clinical union (69-4). If clinical union is not present, apply a close fitting short leg cast, as in Fig. 81-4, for another 6 weeks. If clinical union is present, apply another long leg walking cast for 6 weeks, or a Sarmiento short leg walking cast (81.5). 81.8 Fatigue fractures of the tibia Bones need to get into training in the same ways as soft tissues. If they are repeatedly stressed without adequate training, they may break as ’fatigue fractures’. This can happen when an athlete starts sudden training, when a raw recruit starts marching, or when an invalid gets out of bed. Fatigue fractures start without any history of injury as microscopic lesions which steadily progress. The first symptoms are bone pain at night after heavy exercise, then pain after ordinary exercise, and finally bone pain during exercise. They are a common cause of undiagnosed pain in: (1) the tibia, (2) the metatarsals (especially the second and third), (3) the calcaneus, and (4) the neck of the femur. The callus that forms presents as a tender bony lump, and the fracture may not be visible on X-rays for 5 weeks. When it does appear, the only signs may be slight periosteal el5 81 The tibial shaft evation and increased density of the cancellous bone. The danger in these fractures is that they may be mistaken for tumours. No treatment is needed, apart from the protection of a plaster gaiter in the tibia. Treatment depends on whether or not there is shortening. If there is significant shortening, a week of calcaneal traction will reduce it. Many of the details described in the Section 81.12 on open fractures also apply to closed ones. 81.9 Closed fractures of the shaft of the tibia in children CLOSED FRACTURES OF THE TIBIA AND FIBULA A child falls, and afterwards refuses to walk. He has few signs and you have to make the diagnosis from his history. X-rays usually show a long spiral fracture with little displacement, commonly in the lower half of his tibia. If the fracture is transverse it may be sufficiently displaced to need reducing. CLOSED TIBIAL FRACTURES IN CHILDREN INCOMPLETE FRACTURES Although neither reduction nor splinting is strictly necessary, apply a long leg walking cast (81.4), for 2 or 3 weeks, as described below, to relieve the child’s pain and prevent his fracture from becoming complete. COMPLETE FRACTURES If there is no significant displacement, apply a long leg walking cast. Anaesthesia is usually unnecessary. If he is too young to co–operate and is in much pain, give him ketamine. If there is significant displacement, anaesthetize the child and reduce it. Elevate the fracture above the level of his heart (Fig. 811), by raising his foot off his bed on pillows. CAUTION! Always split the cast, because nobody will watch the circulation in his foot carefully enough, especially during the night. There is no need to spread it (70-3), unless there are signs that the circulation in his leg is in danger. As soon as the swelling has gone, renew or complete the cast by pulling its split edges together, and binding it round with a plaster bandage. Apply a walking heel, and allow him up with crutches. Let him bear his full weight on his leg as soon as pain allows. Leave the cast on for 6 weeks. When you remove it, he will be unable to walk for the first few days, but full movements will then return quickly. 81.10 Closed fractures of the shaft of the fibula A force applied to the outer side of the patient’s leg can break his fibula transversely anywhere. His tibia remains intact, so there is either no displacement or only a little sideways shift. He is usually able to stand. The muscles of his leg cover the fracture, so that you need X-rays to confirm the diagnosis. Reduction, splinting, and protection are unnecessary, so provided his ankle joint is normal (82.1), get him walking as soon as his soft tissue injury allows. 81.11 Closed fractures of both bones In this fracture a patient twists his leg, and in doing so breaks both the bones in his lower leg obliquely, usually in their lower thirds. The fragments shift laterally, overlap, and rotate. 6 Admit the patient. He needs close observation, because his leg may swell severely. WITHOUT SIGNIFICANT SHORTENING If there is swelling, or signs of threatened ischaemia, maintain the position of the fragments by applying: (1) Medial and lateral slabs from the patient’s foot to his groin held on with crepe bandages.Or, (2) a temporary long leg cast split to allow swelling. When the swelling has subsided, apply a long leg walking cast (81.4), or close the split in the cast he already has. If the fracture is oblique, take care to correct rotation. Then continue weight bearing on crutches. Review him and X-ray the fracture regularly. Wedge (70.7) and replace the cast as necessary. A closed transverse fracture should unite in 12 to 16 weeks. The last 8 weeks can be in a short leg cast, especially if it is a total contact one of the Sarmiento type (81.5). WITH SIGNIFICANT SHORTENING The patient probably has an oblique fracture. Anaesthetize him. Apply medial and lateral slabs as above. Pass a Steinmann pin through his calcaneus (70.11) and rotate his leg to correct any external rotation. Apply 5 kg traction, and raise the foot of his bed 25 cm to counteract it. Put a pillow longitudinally under his leg. This will hold his knee in a comfortable semiflexed position and prevent his heel from pressing on the bed uncomfortably. Leave his leg in traction for a week, and treat its soft parts energetically meanwhile. Encourage him to move his toes, his ankle, and his knee. This period of traction will allow his soft tissues to heal. After a week, remove the pin, apply a long leg cast, and encourage him to walk. Leave the cast on for at least 8 weeks. Then remove it and examine his leg for signs of clinical union (Fig. 69-4). If the fracture has united and is barely springy, apply a close fitting short leg cast (81.5) for 6 to 8 more weeks. Encourage him to walk normally. If the fracture has not united, reapply a long leg cast and continue weight bearing for another 5 weeks, then apply a short leg cast. 81.12 Open fractures of both bones of the lower leg Open fractures of the tibia and fibula are the commonest open fractures in man, and are one of the more unfortunate results of a traffic accident, particularly a motor cycle accident. They vary from a minor cut over a broken bone to the grossest mutilation, and displacement of the bony fragments. This is worst when the wheel of a car has run over a patient’s leg, squashed his muscles, and torn his skin from the underlying fascia over a wide area (54.8). His fracture may be transverse or oblique, or comminuted into many widely scattered pieces. These are dangerous fractures: (1) They are often infected and, if you allow gas gangrene to occur, they can be fatal. (2) 81.12 Open fractures of both bones of the lower leg FRACTURES OF THE TIBIA AND FIBULA fractured femur transverse oblique spiral these take longest to unite, especially if they are in the lower third I malunion fractured tibia and fibula transverse with butterfly fragments transverse and shifted transverse and overlapped ’bayonet position’ severe angulation double tibia and fibula fractures Fig. 81.8: FRACTURES OF THE SHAFTS OF BOTH THE BONES OF THE LOWER LEG. A, transverse, B, oblique and C, spiral fractures. D, a transverse fragment with a butterfly (triangular) fragment. E, a transverse shifted fracture. F, the fragments are in a bayonet position. Never leave a fracture like this. H, double fractures of both bones. I, shows the malunion that may result if a fracture like G is inadequately treated. They are often transverse, and pieces of bone may be lost, so that great care has to be taken to make them unite. (3) If treatment is prolonged, the patient may become very demoralized, and may be away from work so long that he loses his job. (4) Serious complications may occur later, including a stiff ankle, and foot drop. Fortunately, the following method is satisfactory for most cases. A really thorough wound toilet is critical. After this, you must leave the wound open unsutured until the danger of infection is over. Never close it by immediate suture. As soon as it is safe to do so, apply a long leg cast and encourage the patient to walk. The secret of success is early weight bearing while his leg is still in a cast, and while his skin woun is still incompletely healed. Many severe injuries heal dramatically, even some of those which might at first seem to need a bone graft. If a patient’s skin and muscles have been widely damaged, his leg will swell severely. Applying a cast too soon is dangerous, so admit him to allow the swelling to subside, and his soft tissues to start healing, before you apply it. If you apply a cast immediately and discharge him, he may return in great pain 24 hours later with the compartment syndrome (73.7). LEAVE THE PATIENT’S WOUND UNSUTURED UNTIL THE DANGER OF INFECTION IS OVER NEVER ATTEMPT PRIMARY SUTURE OVER AN OPEN FRACTURE EARLY WEIGHT BEARING IS ESSENTIAL Two periods of treatment are necessary. The first is a period of provisional treatment during which the spread of infection is prevented by a thorough wound toilet. After this you can leave the patient’s wound open to the air to allow drainage, to reduce the risk of sepsis, and to prevent gas gangrene. Antibiotics are no substitute for an adequate wound toilet. Close his wound a few days later by delayed primary suture or skin grafting. Apply a cast and start the period of definitive treatment as soon as: (1) the danger of gas gangrene is over, (2) most of the swelling has gone, and (3) most of his wound (not necessarily all of it) has been covered by skin. He is usually ready for a cast at 5 to 17 days; his skin wound will continue to heal while he is walking about in it. If his soft tissues have not been widely damaged, you can 7 81 The tibial shaft apply a long leg cast immediately, as described below, but this is not so easy, nor so safe. The first step in reducing an open tibial fracture is to get the fragments into the best position you can through the open skin wound during the wound toilet. After that you can control their position in one of the two ways: (1) You can apply a temporary plaster and bivalve it (70.3), so that you can inspect and treat the patient’s wound. Or, (2) you can apply traction with a Steinmann pin through his calcaneus, or just above his malleoli. A pin through his calcaneus: (a) corrects even severe displacement, (b) does not obstruct the circulation in his leg, (c) leaves his wound open for inspection and treatment, and (d) requires that the foot of his bed be raised. This is useful, because it helps to reduce swelling at the fracture site. The main disadvantage of a pin through the calcaneus is the remote possibility of osteomyelitis (7.13). There is less risk of this if you put the pin through his lower tibia, but traction there is less well placed mechanically, and it may pull the lower fragment of his tibia up into the wound, as in A, Fig. 81-9. Treat the patient rather than his X-ray, and aim for a leg which works, rather than for a beautiful film. This method needs good plaster technique, and sometimes careful wedging (70.7). He may need much encouragement to make him walk in his cast, especially if he can feel his broken bones grating against one another with each step he takes. Persuade your nurses to encourage him to do this. If they fail, persuade him yourself. A THOROUGH WOUND TOILET IS CRITICAL GET HIM WALKING EARLY IN A CAST Brown P.W. and Urban J.G. Early weight bearing the treatment of open fractures of the tibia. Prepare the skin of his leg with an antiseptic solution, as for any surgical operation. Drape it and do a careful surgical toilet. If the tissue is tense, incise the fascial planes to prevent the compartment syndrome and minimise the risk of gas gangrene (54.13). Remove any dirt–encrusted fat and muscle. Excise a millimetre or two of skin from the edges of the wound. If there are any loose bone fragments, leave them, especially if they have any attached periosteum. They may settle down and act as a bone graft. If the wound becomes infected, remove them at your next wound toilet. When the whole of his wound is surgically clean, take off the tourniquet. Stop bleeding with packs (3.1), and the minimum number of the fine ligatures. Cover it with sterile gauze for delayed closure, or delayed skin grafting later. Some surgeons use hypochlorite pressure dressings. CAUTION! (1) Don’t close his open wound by primary suture. (2) Avoid relaxing incisions, rotation flaps, and pedicle grafts as primary procedures. EARLY TREATMENT OF THE FRACTURE Immediately the wound toilet is complete, and while the patient is still anaesthetized, reduce the fracture as best you can. Bringing the fragments into contact with one another is more important than correcting angulation, because you can correct this later while the bone ends are still sticky. If his fracture is transverse, try to get as much as possible of the diameters of the fragments to touch one another. Even if they only touch over part of their circumference, this will be useful. Bringing them into contact can be difficult if there is soft tissue between them. Don’t leave them in the bayonet position, as in F, Fig. 81-8. If reducing overlap is difficult, insert a periosteal elevator or some other suitable instrument between the bone ends, and lever them into po- TWO KINDS OF PROVISIONAL TRACTION Journal of Bone Joint Surgery. 1969;51A:59–75 No! Nicoll E.A. Fractures of the Tibial Shaft. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1964;46B:373. OPEN FRACTURES OF THE TIBIA AND FIBULA A This section applies to any fracture over which there is any skin wound, or skin which looks as if it might break down. Have you felt the patient’s dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses and tested the sensation in his toes? Admit him. He needs careful observation. Give him penicillin, and tetanus prophylaxis (54.11). For the use of broad spectrum antibiotics, see Sections 2.7 and 54.1. PROVISIONAL TREATMENT FOR OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURES Resuscitate and anaesthetize the patient, give him a general or a subarachnoid (spinal) anaesthetic (7.4), or ketamine (A 8.2). THE EARLY WOUND TOILET must be thorough (54.1). If necessary, apply a tourniquet. Scrub the skin around the patient’s wound with water, soap, and a soft nail brush, to remove all ingrained dirt. Sponge his wound clean. Pour plenty of water over it, and if it is severely contaminated, syringe it forcibly with saline. 8 Traction through the tibia may raise the lower fragment Traction through the calcaneus keeps the lower fragment in place B Fig. 81.9: TWO METHODS OF PROVISIONAL TRACTION FOR TIBIA FRACTURES. A, traction through the lower tibia may pull the lower fragment out of the wound. B, traction through the calcaneus keeps the lower fragment in place, but if osteomyelitis occurs it will be very troublesome. After Charnley with kind permission. 81.12 Open fractures of both bones of the lower leg sition. If you cannot get enough traction on the patient’s foot to reduce the fragments, insert a Steinmann pin temporarily in his calcaneus and exert traction on this. Do this now while he is still in the theatre. CAUTION! In a transverse fracture avoid any end to end distraction, no matter how slight, it is the great enemy of union. If his fracture is oblique or comminuted, calcaneal traction (see below) is particularly useful. You may be unable to prevent mild overlap. Some separation of the fragments is inevitable, but they will unite slowly. If a pointed fragment of bone is sticking through the patient’s skin and you cannot easily reduce it, nibble it away. Dress his wound, then splint his leg with medial and lateral slabs, held on with crepe bandages. This will let you inspect and treat it by unwrapping them. CAUTION! (1) If his soft tissue injury is severe, remember the possibility of gas gangrene (54.13). Beware, especially, of fever, pain, a rising pulse, and a falling blood pressure. (2) Watch also for signs of the compartment syndrome (81.14)—severe pain, inability to move his toes, and numb toes. THREE DAYS LATER Open up the dressings and look at the patient’s wound; there are several possibilities. If his wound looks clean, and you can close it without tension, consider delayed primary suture. If his wound looks clean, but you cannot close it without tension, graft it with split skin (57.2). You may need to repeat this on about the eighth and if necessary again on the thirteenth day. Don’t try grafting until there are good granulations to put the graft on. Don’t let him start weight bearing until the graft has taken. If his wound is very dirty, toilet it again surgically in the theatre. DEFINITIVE TREATMENT FOR OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURES FIT A LONG LEG WALKING CAST When the patient’s wound is mostly closed by skin, or a graft is taking, usually at 14 to 17 days, fit him with a long leg walking cast (81.4). The swelling will have subsided, so there is no need to split it. Even so, watch the circulation in his foot carefully. Put a dressing over his wound, but preferably don’t window the cast (70.7). Inspect his wound when the cast needs changing. Apply the cast with his ankle in 10◦ of dorsiflexion, unless this position causes posterior angulation of the fragments, as it may do in a lower third fracture when a piece of the tibia is comminuted anteriorly. If dorsiflexion does cause posterior angulation, leave his foot in equinus, but fit a stirrup as in Fig. 81-11, or a high enough walking heel (81.3). If possible, raise his opposite shoe. Make the cast strong enough to last 6 to 8 weeks. Raise his leg for 12 hours after fitting the cast. EARLY WALKING FOR OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURES The next day allow the cast to rest on the floor. Give the patient crutches and encourage him to walk on his broken leg, bearing as much weight as he can tolerate. Let him gradually increase the weight he bears on his cast, but don’t push him to the point of pain. If he feels crepitus, or he feels the fragments are moving, tell him to persist. Explain that this is normal and will help his bones to unite. CAUTION! Early walking is critical to the success of this method. In the early days, when he is not walking, tell him to keep his leg raised. This will minimize swelling and make it more comfortable. When he is bearing nearly all his weight on his injured leg, exchange his crutches for a stick. Most patients reach full weight bearing in a few weeks, and some within a few days. Send him home when he is walking well. Review him in 3 weeks. Make sure he is walking properly, and his plaster is in good condition. IF NECESSARY, CONTROL ANGULATION If an adult’s fracture is angulated more than 5◦ in any direction, correct it by renewing the plaster or, less safely, if plaster bandages are scarce, by careful wedging (70.7). Don’t do this immediately. The best time is usually at 3 to 4 weeks in an adult, and sooner in a child. Be sure you do it while the patient’s bone ends are still sticky, and before they have united. Use an opening wedge a little above the fracture, so that pressure does not increase over it. If his leg is angulated in two planes, you may be able to control it with one wedge, or you may need two. This may make the cast look ugly, but it will improve the final look of his leg. CAUTION! Don’t try to wedge a cast more than once— change it. The risk of pressure sores is too great. DRESSINGS Change the dressings when you change the cast. This is better than repeatedly changing them through a window. CHANGING A LONG LEG CAST IN AN OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURE If the cast is snug and comfortable, leave it for 5 to 8 weeks. Change it earlier if it becomes loose or uncomfortable, because the position of reduction is easily lost inside a loose cast. If plaster bandages are scarce, you may be able to cut a longitudinal strip out of a loose cast and close it up. Change it if pus or blood soaks through excessively and stinks unbearably. A patient may need as few as 3 casts or as many as 15. He will probably need about 6. TEST FOR CLINICAL UNION At 5 to 8 weeks, remove the cast and examine the patient’s fracture for signs of clinical union (Fig. 69-4). If you are in doubt, X-ray it and renew the TEMPORARY CALCANEAL TRACTION This is the injury on the first day, if the wound looks clean on the third day, it will be grafted fragments approximately aligned Fig. 81.10: PROVISIONAL TRACTION FOR AN OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURE. This is useful if the bone is very comminuted, but don’t apply it for more than 2 weeks. Kindly contributed by Peter Bewes. 9 81 The tibial shaft cast. Don’t discard a full length cast until: (1) The patient can walk without crutches, and (2) there are signs of clinical union as shown by: (a) no tenderness at the fracture site, and (b) mature bridging callus in the X-ray. The clinical signs are more important than the X-ray. Don’t leave a long leg cast on too long, because it will prevent him from bending his knee, and make it stiff. Fit a short leg cast as soon as you can. Spiral or transverse fractures reach clinical union more quickly, usually in about 12 weeks in adults, especially if a patient starts weight bearing early. A short oblique fracture usually takes 12 to 16 weeks to unite, but it may occasionally take a year or more, especially in the lower third of the leg where delayed union is a particular danger, and particularly if you unwisely treated it in prolonged traction! A SHORTER CAST As soon as there is good clinical union, give the patient a shorter cast. If a middle third fracture of his tibia is now firm, give him a well padded plaster gaiter (81.6), or a Sarmiento total contact cast (81.5), because fractures here need less protection than they do elsewhere. If his fracture is anywhere else in his tibia, apply a Sarmiento cast which includes his foot. Keep him walking and gradually increase his range of activities. CAUTION! Pain and tenderness over a fracture site are signs that clinical union is not yet complete, so continue to protect his fracture in a short leg cast. it is almost certain to cause a slough on the dorsum of his foot. USING A BÖHLER–BRAUN FRAME This can be used for provisional treatment, and is shown in Fig. 79-10. After the first few days it is much less effective than early mobility in a long leg walking cast. APPLYING A LONG LEG CAST IMMEDIATELY If a patient’s soft tissue injury is minimal, some surgeons apply a long leg cast without a period of provisional treatment. If you are inexperienced, this is a method to be applied with extreme caution. After the wound toilet, align the fragments with the patient’s lower leg hanging over the end of the table. Sit, and rest his foot on your knee, adjusting the height of the table to make this possible. Study the X-ray and manipulate the fragments into position. EXTERNAL FIXATION WITH TWO STEINMANN PINS If a patient has a severe soft tissue injury, you may be able to apply two Steinmann pins, one well above and one well below the fracture, and incorporate these in a cast, if necessary with a window, and get him walking. Later, you may be able to remove the bottom pin and mould the cast around his ankle. This will minimize shortening, but union may be slower than if you accept it, and treat him as above. 81.13 Difficulties with fractures of the tibia ALTERNATIVE METHODS FOR OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURES A STEINMANN PIN TO STOP A SHORT LEG CAST ROTATING A long leg cast is heavy, and because it prevents a patient bending his knee, he cannot easily turn himself in bed, so it makes nursing difficult. A long leg cast is thus contraindicated: (1) if he is oId, or (2) if he has other serious injuries, such as a femoral or malleolar fracture. Under these conditions apply a short leg walking cast and prevent rotation by incorporating a Steinmann pin in it. Insert the pin obliquely 1.5 to 2 cm distal to his tibial tuberosity (70.11). Make sure the cast allows him to bend his knee. Don’t allow him to bear weight on on the cast while the pin is in it, because the pin may break. Remove the pin as soon as is practical, so as to allow him to bear weight on the fragments of his tibia. TEMPORARY CALCANEAL OR LOWER TIBIAL TRACTION TO ALIGN THE FRAGMENTS If a fracture is very comminuted, or a patient’s wound needs repeated toileting, traction may be useful to hold the fragments approximately in place during the first week or two only. Insert a Steinmann or a Denham pin through the patient’s calcaneus, or his lower tibia just above his ankle; apply 5 to 7 kg traction, and raise the foot of his bed 25 cm. This will align his leg and make him comfortable. Don’t leave the pin in for longer than is necessary, preferably not more than 2 weeks. Keep him exercising his foot while he is on traction; this will reduce oedema and minimize stiffness. When the fragments have become sticky enough to stay in place on their own, remove the traction, allow his leg to shorten to a stable position, and then apply a long leg cast. CAUTION! (1) Don’t apply so much weight as to produce distraction at the fracture site or endanger the blood supply of the patient’s leg. (2) Don’t apply traction to a cast unless you have put a pin into his tibia and incorporated this in the cast, because 10 If a piece of a patient’s tibia is missing, treatment depends on how much is missing, and where. Try to make the broken ends of the tibia impact. Making the bone ends touch is more important than maintaining length. DIFFICULTIES WITH OPEN TIBIAL FRACTURES If a patient’s FOOT IS SO SEVERELY INJURED that you are thinking about amputation, preserve it if it still has a pulse and normal sensation. Provided you do a thorough wound toilet and avoid the danger of gas gangrene, you can, if necessary, amputate later. Raise his leg, keep it cool, with ice if possible, and resuscitate him meanwhile. Even the severest bony injury is never by itself an indication for amputation. If a small PIECE OF TIBIA IS MISSING, it will probably heal adequately. If his tibia is intact posteriorly, but a PIECE OF TIBIA IS MISSING ANTERIORLY, the lower fragment is in danger of bending forwards, so refer him. If this is Impossible, prevent forward angulation by putting his foot into plaster in equinus, as in Fig. 81-11, until the comminuted area has stabilized. Fit a metal stirrup on it instead of a walking heel. This will let him walk on his injured leg, even though his ankle is in equinus. If LESS THAN 3 cm OF TIBIA IS MISSING, wait for the wound to heal, and for the patient’s skin to become clean. If his fibula has not already been broken by the injury, make a separate lateral incision far enough above or below his tibial fracture to leave some stability at the fracture site. Cut his fibula obliquely with a sharp osteotome. Push the ends of his tibia together, so that the fragments of his fibula overlap. If absolutely necessary, you can remove a piece of fibula. Apply a long leg cast and get him walking and weight bearing as soon as possible. His tibia will unite, but it will take 81.13 Difficulties with fractures of the tibia several months. If necessary, raise his shoe to compensate for shortening. If MORE THAN 3 cm OF TIBIA IS MISSING, apply calcaneal traction, but don’t try to maintain its full length. Traction will stabilize his leg and make a wound toilet easier. Refer him for an operation in which cancellous bone chips or part of his fibula is used to bridge the missing portion. When this i s done, his fibula may hypertrophy surprisingly. If referral is impossible, you will have to treat him as above. CAUTION! Don’t attempt any early bone nibbling to remove supposed dead or infected bone. Instead, encourage early weight bearing, and hope that the patient’s tibia will unite posteriorly. Then, do any bone nibbling that is needed. If PUS GATHERS IN HIS WOUND, it fails to heel, and his tibia fails to unite, open the wound widely so that it can drain. Remember that wounds drain by gravity so that the bottom of a pus pocket must be open. Infection may be caused by an inadequate wound toilet or by dead bone. Continue irrigating and toileting the wound as necessary. As soon as it is reasonably clean, put him into a long leg cast and get him walking. If OSTEOMYELITIS occurs, X-ray the fracture and look for sequestra. If you find them, take the patient to the theatre, remove all pieces of dead bone, irrigate his wound, and A PIECE OF TIBIA IS MISSING A cut his fibula here with an osteotome D B provide dependant drainage, or, better, suction drainage. Alterantively, raise his leg on a Böhler–Braun splint, and apply calcaneal traction. Lay a catheter alongside the wound, or use the tube of a drip set with multiple holes cut in it. Irrigate his wound with saline (the addition of penicillin i s optional), and let it drip into a basin underneath the splint. Sterile saline is expensive, so you may have to use clean tap water and salt. Irrigation needs much care and attention, and will require all the nursing skills you have. Later, reapply the cast, keep the patient walking, and change the cast when it becomes soft, or stinks excessively. If GAS GANGRENE occurs, immediate amputation may be necessary to save the patient’s life. Treat it as in Section 54.13. The way to prevent it is: (1) to explore and excise his wound properly, (2) to open up all the fascial spaces where pressure could build up, and (3) to lay his wound open without an encircling cast after you have explored it. If there is DEAD BONE at the bottom of an infected wound, you may be able to remove it without anaesthesia, as in B Fig. 81-12, because bone is insensitive. Use a bone gauge or chisel, and hammer, to remove any bone which looks white and does not become pink or bleed, and especially any exposed bone, until you get to healthy bleeding bone. Later, when granulations have appeared, graft it, as in Section 57.2. Don’t remove too much bone, or you will weaken the patient’s tibia. Removing it to a depth of 1 or 2 mm is usually enough. Let the patient carry on walking, and look at his wound a week later. If any exposed bone remains, repeat the process. Go on doing this until healing is complete. If a patient’s TIBIA HAS NOT UNITED after 16 weeks, don’t be alarmed. Fractures of the upper third of the tibia usually unite quite easily. It is fractures of the lower third that often don’t. Even so, most of them unite by 16 weeks, but some take a year or even 2 years. Give him 6 months to unite in a well fitted short leg walking cast (81.5). If there is no union at 6 months consider referring him. If his tibia has not united in a year, he will probably need bone grafting. Here are some reasons for non-union. Faulty treatment may be to blame. C SKIN GRAFTING AN EXPOSED TIBIA A chip away dead white bone until you get to healthy bleeding bone B exposed bone in an open fracture anterior comminution C graft the healthy exposed bone rubber foot in equinus Fig. 81.11: A PIECE OF TIBIA IS MISSING. A, if a piece of the patient’s tibia is missing anteriorly, his fibula will probably be broken also, so you can let the fragments of his fibula over ride one another and push those of his tibia together. If his fibula is intact, cut it. B, C, and D, if his tibia is comminuted anteriorly, fit him with a stirrup with his foot in the equinus position. If you don’t have a stirrup, fit a wooden block under his heel. Kindly contributed by John Stewart. Fig. 81.12: SKIN GRAFTING AN EXPOSED TIBIA. A, chip away dead bone. B, exposed bone at the bottom of an open fracture. C, grafting healthy granulations. With the kind permission of Peter London. 11 81 The tibial shaft He did not exercise his broken leg enough The fibula unites quickly, and may hold the two ends of his tibia apart, and so prevent them from uniting. Prevent this by teaching him to contract the muscles of his foot, and get him walking as soon as possible. Each step he makes will help his broken tibia to unite. Unfortunately, his other injuries may prevent early exercise. His tibia was extensively injured In severe open fractures, in which large bone fragments have protruded through the skin and been stripped of their periosteum, much of the injured bone dies. The callus that forms has to cross a wider gap, so that union and consolidation take longer, and the risk of non–union is greater. You applied too much traction, or tried internal fixation under unsatisfactory conditions. Both of these errors will delay union, especially if a patient has been discouraged from walking early. His wound has become infected. Infection delays union greatly, particularly if pus has accumulated because you have not opened up the patient’s tissues and allowed it to drain freely through his open wound. His ankle was immobilized in equinus without the application of a stirrup. When this has happened he cannot put his foot to the ground without bending the callus around his fracture, and causing hinging stresses which lead to healing with fibrous tissue, rather than with bone. Either immoblize his ankle in neutral, or if you have to immobilize it in equinus, fit the cast with a stirrup. If there is MALUNION, it can take several forms: (1) Shortening is usually minimal and unimportant (78.1). If the patient is fortunate enough to wear shoes, you can compensate for a loss of up to 4 cm by raising the heel of one of them, and lowering the heel of the other one. (2) Angulation is serious and unnecessary. Prevent it by: (a) aligning the fragments carefully to begin with, (b) wedging or changing the patient’s cast early (70.7), and (c) making sure that when he starts weight bearing, he does so in a cast which fully supports the fracture. It is not the weight bearing that causes the malunion, it is improper casting— not having a snug cast. Valgus or varus malunions are more serious than backward or forward bowing, because he can compensate for them less easily. (3) Rotation deformities in which a patient’s foot points inwards or outwards are also serious. Prevent them by making sure that his foot points in the same direction relative to his patella on the injured side as it does on the normal one (Fig. 81-2). If his SKIN WILL NOT HEAL COMPLETELY over the front of his tibia, despite one or two skin grafts, forget this for the present, and keep him walking in a cast. Remove the cast after 5 to 6 weeks, and look at the wound. It will probably have healed. If HIS FOOT SWELLS and he is in a cast, bring him into hospital overnight. Let him sleep with his foot raised. The following day before you allow him out of bed apply a new cast which fits properly. If he has been in a cast for many weeks, his foot is sure to swell when it is removed. If necessary, compress it with 12 an elastic bandage, elevate his leg at night, and continue to exercise it. If a patient’s FOOT IS STIFF AND PAINFUL, there is little you can do. There is always some stiffness, especially after a fracture of the lower third of the tibia, due to scar tissue forming around the extensor tendons. The preventable causes include the tragedy of Volkmann’s contracture (70.4), or unnecessarily applying a cast with the patient’s foot in equinus. If he CANNOT DORSIFLEX HIS ANKLE (foot drop): (1) He might have injured his common peroneal nerve at the time of the accident, so when you first see him, ask him to dorsiflex his foot so that you can test the sensation on its dorsum, and record your findings. (2) His common peroneal nerve may also have been injured by a cast, especially if it was not padded around the neck of his fibula. If his paralysis persists, he will need a brace to support his foot. (3) In the early days pressure in the anterior compartment of his leg can prevent him from raising his foot. If this happens, decompress his leg urgently as described in Section 81.14. DON’T LET A PATIENT WALK ABOUT IN A LOOSE CAST, OR THE FRAGMENTS WILL MOVE OUT OF POSITION DON’T GIVE UP HOPE TOO EARLY early x−ray of fracture inside a cast successful union Fig. 81.13: SKIN GRAFTING AN EXPOSED TIBIA. A, chip away dead bone. B, exposed bone at the bottom of an open fracture. C, grafting healthy granulations. With the kind permission of Peter London. BRING THE ENDS OF THE PATIENT’S TIBIA TOGETHER 81.14 The compartment syndrome in the leg If a patient with a lower leg injury: (1) has severe pain, (2) cannot move his toes, or (3) has numb toes, be careful. These 81.14 The compartment syndrome in the leg DECOMPRESSION FOR THE COMPARTMENT SYNDROME THE COMPARTMENT SYNDROME anterior compartment A lateral compartment skin rotated to expose peroneal muscles If a patient with an injured lower leg complains of severe pain, or cannot move his toes, believe him. If his leg is in a cast, split it, spread it, and elevate his leg. If this does not rapidly relieve his symptoms, remove the cast. If his symptoms persist, proceed urgently with fasciotomy. WHICH COMPARTMENT? Stretching an ischaemic muscle causes pain so: If flexing his foot and toes causes pain, his anterior compartment is ischaemic. If extending his foot and toes causes pain, his posterior compartment is ischaemic. B FASCIOTOMY FOR THE COMPARTMENT SYNDROME deep posterior compartment posterior compartment blunt scissors or closed artery forceps scissors thrust deep to decompress the deep posterior department posterior tibial nerve and vessels Fig. 81.14: TREATING THE COMPARTMENT SYNDROME. A, incisions for the lateral and posterior compartments. B, opening up the deep posterior compartment. This diagram also shows how you can slide the skin incision you have used to open the lateral compartment forwards, so that you can also open the anterior compartment through it. Kindly contributed by Peter Bewes. are signs of the compartment syndrome which can be followed by Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture, as in the arm (70.4). A normal pulse and apparently normal filling of his nail beds do not exclude it. When a patient’s fracture is reduced his pain should become less. Severe postoperative pain is thus the critical early sign. There are four musclar compartments in the lower leg, separated from one another by strong fascia: (1) The lateral compartment contains a patient’s peroneal muscles. (2) The anterior compartment contains the extensor muscles of his ankle and toes. (3) The superficial part of the posterior compartment contains his gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. (4) The deep posterior compartment contains his deep flexors. After a fracture, or even after bruising of his lower leg, blood and oedema fluid may collect in all, or any, of these compartments under such pressure that the circulation to his foot is obstructed. Unless you immediately open up each compartment in turn through a generous longitudinal incision, Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture or gangrene may follow. The after effects of a fasciotomy are minimal, but ischaemic muscle never recovers. Medial incision Make a longitudinal 15 cm incision on the medial side of the patient’s leg. Cut through the deep fascia from his knee to his ankle. Incise the turgid, dark, reddish blue, ischaemic muscle of his posterior compartment. Lateral incision Make a similar 15 cm longitudinal incision on the outer side of his leg. Incise the fascia and the muscle directly underneath it, and decompress his peroneal compartment. Slide the skin incision anteriorly over the subcutaneous tissue, as shown by the arrow in B, Fig. 81-14, and incise the muscle under it so as to decompress his anterior tibial compartment. This will enable you to decompress both compartments through the same incision. If the circulation returns to his foot, no further incisions are necessary. If the circulation does not return to his foot in a few minutes, deepen the medial incision to open up his deep posterior compartment. Push scissors deeply into it and open the blades, as if you were exploring an abscess by Hilton’s method (Fig. 5-3). Don’t use a knife in the depths, or you may cut his posterior tibial artery, or his tibial nerve. If he has a fracture, treat this by calcaneal traction until definitive treatment is possible later. CAUTION! Don’t apply a cast until the swelling has subsided. LATER TREATMENT The compartments cannot be closed after these incisions, so leave them wide open, covered with gauze. They will close as the swelling subsides. If necessary, close the wound with a skin graft, or delayed primary suture. 13