Consonance and dissonance in music theory and psychology

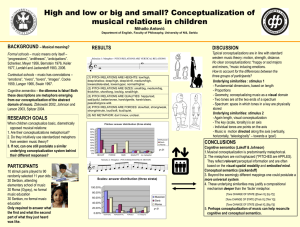

advertisement